Assam

Assam (/æsˈsæm, əˈsæm/,[10][11] Assamese: [ˈɔxɔm] (![]() listen)) is a state in northeastern India, situated south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of 78,438 km2 (30,285 sq mi). The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur to the east; Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram and Bangladesh to the south; and West Bengal to the west via the Siliguri Corridor, a 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide strip of land that connects the state to the rest of India. It is also one of the world's most populous subdivisions. Assamese is the official and most commonly spoken language of the state, followed by Bengali, which is official in the Barak Valley and Bodo which is official in Bodoland Territorial Region.

listen)) is a state in northeastern India, situated south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of 78,438 km2 (30,285 sq mi). The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur to the east; Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram and Bangladesh to the south; and West Bengal to the west via the Siliguri Corridor, a 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide strip of land that connects the state to the rest of India. It is also one of the world's most populous subdivisions. Assamese is the official and most commonly spoken language of the state, followed by Bengali, which is official in the Barak Valley and Bodo which is official in Bodoland Territorial Region.

Assam | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top, left to right: Indian rhinoceros in Kaziranga National Park, Ahom Raja Palace, Kamakhya Temple, Rang Ghar, Kolia Bhomora Setu, IIT Guwahati | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Seal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "O Mur Apunar Desh" (O my Dearest Country) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates (Dispur, Guwahati): 26.14°N 91.77°E | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statehood† | 26 January 1950[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Dispur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Guwahati | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Districts | 33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Body | Government of Assam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Governor | Jagdish Mukhi[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Chief Minister | Sarbananda Sonowal (BJP) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Legislature | Unicameral (126 seats) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Parliamentary constituency | Rajya Sabha (7 seats) Lok Sabha (14 seats) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • High Court | Gauhati High Court | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 78,438 km2 (30,285 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area rank | 16th | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 45−1,960 m (148−6,430 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population (2011) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 31,169,272 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Rank | 15th | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 397/km2 (1,030/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (2019-20) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | ₹3.24 lakh crore (US$45 billion) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Per capita | ₹82,078 (US$1,200) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Official | Assamese[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Additional official | Bengali in Barak Valley[5] Bodo in Bodoland Territorial Region[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IN-AS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2018) | medium · 30th | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy (2011) | 72.19%[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex ratio (2011) | 958 ♀/1000 ♂[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | assam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| † First recognised as an administrative division on 1 April 1911, and led to the establishment of Assam Province by partitioning Province of East Bengal and Assam. ^[*] Assam was one of the original provincial divisions of British India. ^[*] Assam has had a legislature since 1937.[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Assam is known for Assam tea and Assam silk. The state was the first site for oil drilling in Asia.[12] Assam is home to the one-horned Indian rhinoceros, along with the wild water buffalo, pygmy hog, tiger and various species of Asiatic birds, and provides one of the last wild habitats for the Asian elephant. The Assamese economy is aided by wildlife tourism to Kaziranga National Park and Manas National Park, which are World Heritage Sites. Dibru-Saikhowa National Park is famed for its feral horses. Sal tree forests are found in the state which, as a result of abundant rainfall, look green all year round. Assam receives more rainfall than most parts of India; this rain feeds the Brahmaputra River, whose tributaries and oxbow lakes provide the region with a hydro-geomorphic environment.

Etymology

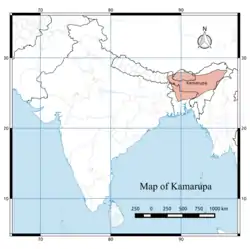

The first dated mention of the region comes from Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century) where it describes a people called Sêsatea,[13] and the second mention comes from Ptolemy's Geographia (2nd century) which calls the region Kirrhadia after the Kirata population.[14] In the classical period and up to the 12th century the region east of the Karatoya river, largely congruent to present-day Assam, was called Kamarupa, and alternatively, Pragjyotisha.[15] Though a western portion of Assam as a region continued to be called Kamrup, the Ahom kingdom that emerged in the east, and which came to dominate the entire Brahmaputra valley, was called Assam (e.g. Mughals used Asham); and the British province too was called Assam. Though the precise etymology of Assam is not clear, the name Assam is associated with the Ahom people, originally called Shyam (Shan).[16]

History

Pre-history

Assam and adjoining regions have evidences of human settlement from the beginning of the Stone Age. The hills at the height of 1,500 to 2,000 feet (460–615 m) were popular habitats probably due to availability of exposed dolerite basalt, useful for tool-making.[17] Ambari site in Guwahati has revealed Shunga-Kushana era artefacts including flight of stairs and a water tank which may date from 1st century BCE and may be 2,000 years old. Experts speculate that another significant find at Ambari is Roman era Roman roulette pottery from the 2nd century BCE.[18][19][20]

Legend

According to a late text, Kalika Purana (c. 9th–10th century CE), the earliest ruler of Assam was Mahiranga Danav of the Kachari Danava dynasty, which was removed by Naraka and who established the Naraka dynasty. The last of these rulers, also Naraka, was slain by Krishna. Naraka's son Bhagadatta became the king, who (it is mentioned in the Mahabharata) fought for the Kauravas in the battle of Kurukshetra with an army of kiratas, chinas and dwellers of the eastern coast. At the same time towards the east in central Assam, Asura Kingdom was ruled by another Kachari line of kings.[21]

Ancient era

Samudragupta's 4th-century-CE Allahabad pillar inscription mentions Kamarupa[22] and Davaka (Central Assam)[23] as frontier kingdoms of the Gupta Empire.

Davaka was later absorbed by Kamarupa, which grew into a large kingdom that spanned from Karatoya river to near present Sadiya and covered the entire Brahmaputra valley, North Bengal, parts of Bangladesh and, at times Purnea and parts of West Bengal.[24]

The kingdom was ruled by three dynasties who traced their lineage from a mleccha or Kirata Naraka;[25] the Varmanas (c. 350–650 CE), the Mlechchha dynasty (c.655–900 CE) and the Kamarupa-Palas (c. 900–1100 CE), from their capitals in present-day Guwahati (Pragjyotishpura), Tezpur (Haruppeswara) and North Gauhati (Durjaya) respectively. All three dynasties claimed descent from Narakasura.

In the reign of the Varman king, Bhaskaravarman (c. 600–650 CE), the Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the region and recorded his travels. Later, after weakening and disintegration (after the Kamarupa-Palas), the Kamarupa tradition was extended to c. 1255 CE by the Lunar I (c. 1120–1185 CE) and Lunar II (c. 1155–1255 CE) dynasties.[17]

Medieval era

The Chutiya (1187–1673 CE), a Bodo-Kachari group by origin, held the regions on both the banks of Brahmaputra with its domain in the area eastwards from Vishwanath (north bank) and Buridihing (south bank), in Upper Assam and in the state of Arunachal Pradesh. It was partially annexed in the early 1500s by the Ahoms, finally getting absorbed in 1673 CE. The rivalry between the Chutiyas and Ahoms for the supremacy of eastern Assam led to a series of battles between them from the early 16th century until the start of the 17th century, which saw great loss of men and money.

The Dimasa, another Bodo-Kachari dynasty, (13th century-1854 CE) ruled from Dikhow River to central and southern Assam and had their capital at Dimapur. With the expansion of Ahom kingdom, by the early 17th century, the Chutiya areas were annexed and since c. 1536 CE the Kacharis remained only in Cachar and North Cachar, and more as an Ahom ally than a competing force.

The Ahoms, a Tai group, ruled Upper Assam.[26] The Shans built their kingdom and consolidated their power in Eastern Assam with the modern town of Sibsagar as their capital. Until the early 1500s, the Ahoms ruled a small kingdom in Sibsagar district and suddenly expanded during King Suhungmung's rule taking advantage of weakening rule of Chutia and Dimasa kingdoms. By 1681, the whole track down to the border of the modern district of Goalpara came permanently under their sway. Ahoms ruled for nearly 600 years (1228–1826 CE) with major expansions in the early 16th century at the cost of Chutia and Dimasa Kachari kingdoms. Since c. the 13th century CE, the nerve centre of Ahom polity was upper Assam; the kingdom was gradually extended to the Karatoya River in the 17th or 18th century. It was at its zenith during the reign of Sukhrungphaa or Sworgodeu Rudra Sinha (c. 1696–1714 CE).

The Koch, another Bodo-Kachari dynasty, established sovereignty in c. 1510 CE. The Koch kingdom in Western Assam and present-day North Bengal was at its zenith in the early reign of Nara Narayan (c. 1540–1587 CE). It split into two in c. 1581 CE, the western part as a Mughal vassal and the eastern as an Ahom satellite state. Later, in 1682, Koch Hajo was entirely annexed by the Ahoms.

Despite numerous invasions, mostly by the Muslim rulers, no western power ruled Assam until the arrival of the British. Though the Mughals made seventeen attempts to invade, they were never successful. The most successful invader Mir Jumla, a governor of Aurangzeb, briefly occupied Garhgaon (c. 1662–63 CE), the then capital, but found it difficult to prevent guerrilla attacks on his forces, forcing them to leave. The decisive victory of the Assamese led by general Lachit Borphukan on the Mughals, then under command of Raja Ram Singha, in the Battle of Saraighat in 1671 almost ended Mughal ambitions in this region. The Mughals were comprehensively defeated in the Battle of Itakhuli and expelled from Lower Assam during the reign of Gadadhar Singha in 1682 CE.[27]

Colonial era

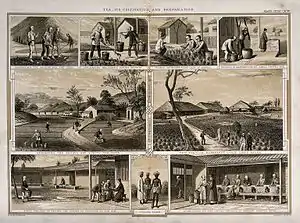

The discovery of Camellia sinensis in 1834 in Assam was followed by testing in 1836–37 in London. The British allowed companies to rent land from 1839 onwards. Thereafter tea plantations proliferated in Eastern Assam,[28] where the soil and the climate were most suitable. Problems with the imported Han Chinese labourers from China and hostility from native Assamese resulted in the migration of forced labourers from central and eastern parts of India. After initial trial and error with planting the Chinese and the Assamese-Chinese hybrid varieties, the planters later accepted the local Camellia assamica as the most suitable variety for Assam. By the 1850s, the industry started seeing some profits. The industry saw initial growth, when in 1861, investors were allowed to own land in Assam and it saw substantial progress with the invention of new technologies and machinery for preparing processed tea during the 1870s.

Despite the commercial success, tea labourers continued to be exploited, working and living under poor conditions. Fearful of greater government interference, the tea growers formed the Indian Tea Association in 1888 to lobby to retain the status quo. The organisation was successful in this, but even after India's independence, conditions of the labourers have improved very little.[29]

In the later part of the 18th century, religious tensions and atrocities by the nobles led to the Moamoria rebellion (1769–1805), resulting in tremendous casualties of lives and property. The rebellion was suppressed but the kingdom was severely weakened by the civil war. Political rivalry between Prime Minister Purnananda Burhagohain and Badan Chandra Borphukan, the Ahom Viceroy of Western Assam, led to an invitation to the Burmese by the latter,[30][31][32][33] in turn leading to three successive Burmese invasions of Assam. The reigning monarch Chandrakanta Singha tried to check the Burmese invaders but he was defeated after fierce resistance. And Ahom occupied Assam was captured by the Burmese[34][35][36]

A reign of terror was unleashed by the Burmese on the Assamese people,[37][38][39][40] who fled to neighbouring kingdoms and British-ruled Bengal.[41][42] The Burmese reached the East India Company's borders, and the First Anglo-Burmese War ensued in 1824. The war ended under the Treaty of Yandabo[43] in 1826, with the Company taking control of Western Assam and installing Purandar Singha as king of Upper Assam in 1833. The arrangement lasted till 1838 and thereafter the British gradually annexed the entire region. Thereafter the court language and medium of instruction in educational institutions of Assam was made Bengali, instead of Assamese. Starting from 1836 until 1873, this imposition of a foreign tongue created greater unemployment among the People of Assam and Assamese literature naturally suffered in its growth.[44][45]

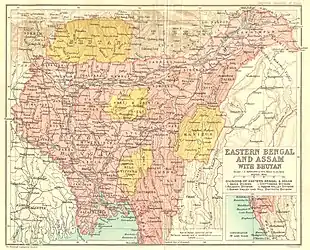

Initially, Assam was made a part of the Bengal Presidency, then in 1906 it was made a part of Eastern Bengal and Assam province, and in 1912 it was reconstituted into a chief commissioners' province. In 1913, a legislative council and, in 1937, the Assam Legislative Assembly, were formed in Shillong, the erstwhile capital of the region. The British tea planters imported labour from central India adding to the demographic canvas.

The Assam territory was first separated from Bengal in 1874 as the 'North-East Frontier' non-regulation province, also known as the Assam Chief-Commissionership. It was incorporated into the new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905 after the partition of Bengal (1905–1911) and re-established in 1912 as Assam Province .[46]

After a few initially unsuccessful attempts to gain independence for Assam during the 1850s, anti-colonial Assamese joined and actively supported the Indian National Congress against the British from the early 20th century, with Gopinath Bordoloi emerging as the preeminent nationalist leader in the Assam Congress. Bordoloi's major political rival in this time was Sir Saidullah, who was representing the Muslim League, and had the backing of the influential Muslim cleric Maulana Bhasani.[47]

The Assam Postage Circle was established by 1873 under the headship of the Deputy Post Master General.[48]

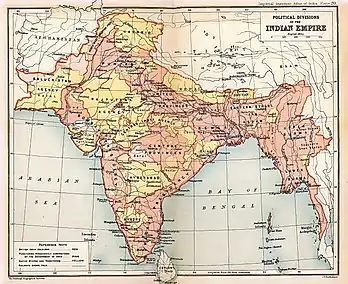

At the turn of the 20th century, British India consisted of eight provinces that were administered either by a governor or a lieutenant-governor. Assam Province was one among the major eight provinces of British India. The table below shows the major original provinces during British India covering the Assam Province under the Administrative Office of the Chief Commissioner.

The following table lists their areas and populations. It does not include those of the dependent Native States:[49]

| Province of British India[49] | Area ( '0002 miles) | Population (in millions) | Chief Administrative Officer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burma | 170 | 9 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Bengal | 151 | 75 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Madras | 142 | 38 | Governor-in-Council |

| Bombay | 123 | 19 | Governor-in-Council |

| United Provinces | 107 | 48 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Central Provinces and Berar | 104 | 13 | Chief Commissioner |

| Punjab | 97 | 20 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Assam | 49 | 6 | Chief Commissioner |

With the partition of India in 1947, Assam became a constituent state of India. The Sylhet District of Assam (excluding the Karimganj subdivision) was given up to East Pakistan, which later became Bangladesh.

Modern history

The government of India, which has the unilateral powers to change the borders of a state, divided Assam into several states beginning in 1970 within the borders of what was then Assam. In 1963, the Naga Hills district became the 16th state of India under the name of Nagaland. Part of Tuensang was added to Nagaland. In 1970, in response to the demands of the Khasi, Jaintia and Garo people of the Meghalaya Plateau, the districts containing the Khasi Hills, Jaintia Hills, and Garo Hills were formed into an autonomous state within Assam; in 1972 this became a separate state under the name of Meghalaya. In 1972, Arunachal Pradesh (the North East Frontier Agency) and Mizoram (from the Mizo Hills in the south) were separated from Assam as union territories; both became states in 1986.[50]

Since the restructuring of Assam after independence, communal tensions and violence remain. Separatist groups began forming along ethnic lines, and demands for autonomy and sovereignty grew, resulting in the fragmentation of Assam. In 1961, the government of Assam passed legislation making use of the Assamese language compulsory. It was withdrawn later under pressure from Bengali speaking people in Cachar. In the 1980s the Brahmaputra valley saw a six-year Assam Agitation[51] triggered by the discovery of a sudden rise in registered voters on electoral rolls. It tried to force the government to identify and deport foreigners illegally migrating from neighbouring Bangladesh and to provide constitutional, legislative, administrative and cultural safeguards for the indigenous Assamese majority, which they felt was under threat due to the increase of migration from Bangladesh. The agitation ended after an accord (Assam Accord 1985) between its leaders and the Union Government, which remained unimplemented, causing simmering discontent.[52]

The post 1970s experienced the growth of armed separatist groups such as the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA)[51] and the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB). In November 1990, the Government of India deployed the Indian army, after which low-intensity military conflicts and political homicides have been continuing for more than a decade. In recent times, ethnically based militant groups have grown. Panchayati Raj Institutions have been applied in Assam, after agitation of the communities due to the sluggish rate of development and general apathy of successive state governments towards Indigenous Assamese communities.

Geography

A significant geographical aspect of Assam is that it contains three of six physiographic divisions of India – The Northern Himalayas (Eastern Hills), The Northern Plains (Brahmaputra plain) and Deccan Plateau (Karbi Anglong). As the Brahmaputra flows in Assam the climate here is cold and there is rainfall most of the month. Geomorphic studies conclude that the Brahmaputra, the life-line of Assam, is an antecedent river older than the Himalayas. The river with steep gorges and rapids in Arunachal Pradesh entering Assam, becomes a braided river (at times 10 mi/16 km wide) and with tributaries, creates a flood plain (Brahmaputra Valley: 50–60 mi/80–100 km wide, 600 mi/1000 km long).[53] The hills of Karbi Anglong, North Cachar and those in and close to Guwahati (also Khasi-Garo Hills) now eroded and dissected are originally parts of the South Indian Plateau system.[53] In the south, the Barak originating in the Barail Range (Assam-Nagaland border) flows through the Cachar district with a 25–30 miles (40–50 km) wide valley and enters Bangladesh with the name Surma River.

Urban centres include Guwahati, one of the 100 fastest growing cities in the world.[54] Guwahati is also referred to as the "Gateway to the North-East India". Silchar, (in the Barak valley) is the second most populous city in Assam and an important centre of business. Other large cities include Dibrugarh, an oil and natural gas industry centre,[55]

Climate

With the tropical monsoon climate, Assam is temperate (summer max. at 95–100 °F or 35–38 °C and winter min. at 43–46 °F or 6–8 °C) and experiences heavy rainfall and high humidity.[53][56] The climate is characterised by heavy monsoon downpours reducing summer temperatures and affecting foggy nights and mornings in winters, frequent during the afternoons. Spring (March–April) and autumn (September–October) are usually pleasant with moderate rainfall and temperature. Assam's agriculture usually depends on the south-west monsoon rains.

Flooding

Every year, flooding from the Brahmaputra and other rivers such as Barak River etc. deluges places in Assam. The water levels of the rivers rise because of rainfall resulting in the rivers overflowing their banks and engulfing nearby areas. Apart from houses and livestock being washed away by flood water, bridges, railway tracks, and roads are also damaged by the calamity, which causes communication breakdown in many places. Fatalities are also caused by the natural disaster in many places of the State.[57][58]

Fauna

Assam is one of the richest biodiversity zones in the world and consists of tropical rainforests,[59] deciduous forests, riverine grasslands,[60] bamboo[61] orchards and numerous wetland[62] ecosystems; Many are now protected as national parks and reserved forests.

Assam has wildlife sanctuaries, the most prominent of which are two UNESCO World Heritage sites[63]-the Kaziranga National Park, on the bank of the Brahmaputra River, and the Manas Wildlife Sanctuary, near the border with Bhutan. The Kaziranga is a refuge for the fast-disappearing Indian one-horned rhinoceros. The state is the last refuge for numerous other endangered and threatened species including the white-winged wood duck or deohanh, Bengal florican, black-breasted parrotbill, red-headed vulture, white-rumped vulture, greater adjutant, Jerdon's babbler, rufous-necked hornbill, Bengal tiger, Asian elephant, pygmy hog, gaur, wild water buffalo, Indian hog deer, hoolock gibbon, golden langur, capped langur, barasingha, Ganges river dolphin, Barca snakehead, Ganges shark, Burmese python, brahminy river turtle, black pond turtle, Asian forest tortoise, and Assam roofed turtle. Threatened species that are extinct in Assam include the gharial, a critically endangered fish-eating crocodilian, and the pink-headed duck (which may be extinct worldwide). For the state bird, the white-winged wood duck, Assam is a globally important area.[64] In addition to the above, there are three other National Parks in Assam namely Dibru Saikhowa National Park, Nameri National Park and the Orang National Park.

Assam has conserved the one-horned Indian rhinoceros from near extinction, along with the pygmy hog, tiger and numerous species of birds, and it provides one of the last wild habitats for the Asian elephant. Kaziranga and Manas are both World Heritage Sites. The state contains Sal tree forests and forest products, much depleted from earlier times. A land of high rainfall, Assam displays greenery. The Brahmaputra River tributaries and oxbow lakes provide the region with hydro-geomorphic environment.

The state has the largest population of the wild water buffalo in the world.[65] The state has the highest diversity of birds in India with around 820 species.[66] With subspecies the number is as high as 946.[67] The mammal diversity in the state is around 190 species.[68]

Flora

Assam is remarkably rich in Orchid species and the Foxtail orchid is the state flower of Assam.[69] The recently established Kaziranga National Orchid and Biodiversity Park boasts more than 500 of the estimated 1,314 orchid species found in India.

Geology

Assam has petroleum, natural gas, coal, limestone and other minor minerals such as magnetic quartzite, kaolin, sillimanites, clay and feldspar.[70] A small quantity of iron ore is available in western districts.[70] Discovered in 1889, all the major petroleum-gas reserves are in Upper parts. A recent USGS estimate shows 399 million barrels (63,400,000 m3) of oil, 1,178 billion cubic feet (3.34×1010 m3) of gas and 67 million barrels (10,700,000 m3) of natural gas liquids in the Assam Geologic Province.[71]

The region is prone to natural disasters like annual floods and frequent mild earthquakes. Strong earthquakes were recorded in 1869, 1897, and 1950.

Demographics

Population

| Population Growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1901 | 3,289,680 | — | |

| 1911 | 3,848,617 | 17.0% | |

| 1921 | 4,636,980 | 20.5% | |

| 1931 | 5,560,371 | 19.9% | |

| 1941 | 6,694,790 | 20.4% | |

| 1951 | 8,028,856 | 19.9% | |

| 1961 | 10,837,329 | 35.0% | |

| 1971 | 14,625,152 | 35.0% | |

| 1981 | 18,041,248 | 23.4% | |

| 1991 | 22,414,322 | 24.2% | |

| 2001 | 26,655,528 | 18.9% | |

| 2011 | 31,205,576 | 17.1% | |

| Source:Census of India[72] | |||

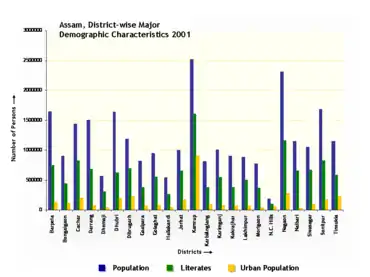

The total population of Assam was 26.66 million with 4.91 million households in 2001.[73] Higher population concentration was recorded in the districts of Kamrup, Nagaon, Sonitpur, Barpeta, Dhubri, Darrang, and Cachar. Assam's population was estimated at 28.67 million in 2006 and at 30.57 million in 2011 and is expected to reach 34.18 million by 2021 and 35.60 million by 2026.[74]

As per the 2011 census, the total population of Assam was 31,169,272. The total population of the state has increased from 26,638,407 to 31,169,272 in the last ten years with a growth rate of 16.93%.[75]

Of the 33 districts, eight districts registered a rise in the decadal population growth rate. Religious minority-dominated districts like Dhubri, Goalpara, Barpeta, Morigaon, Nagaon, and Hailakandi, recorded growth rates ranging from 20 per cent to 24 per cent during the last decade. Eastern Assamese districts, including Sivasagar and Jorhat, registered around 9 per cent population growth. These districts do not have any international border.[76]

In 2011, the literacy rate in the state was 73.18%. The male literacy rate was 78.81% and the female literacy rate was 67.27%.[75] In 2001, the census had recorded literacy in Assam at 63.3% with male literacy at 71.3% and female at 54.6%. The urbanisation rate was recorded at 12.9%.[77]

The growth of population in Assam has increased since the middle decades of the 20th century. The population grew from 3.29 million in 1901 to 6.70 million in 1941. It increased to 14.63 million in 1971 and 22.41 million in 1991.[73] The growth in the Western districts and Southern districts was high primarily due to the influx of people from East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.[52]

The mistrust and clashes between Indigenous Assamese people and Bengali Muslims started as early as 1952,[78][79] but is rooted in anti Bengali sentiments of the 1940s.[80] At least 77 people died[81] and 400,000 people were displaced in the 2012 Assam violence between indigenous Bodos and Bengali Muslims.[82]

The People of India project has studied 115 of the ethnic groups in Assam. 79 (69%) identify themselves regionally, 22 (19%) locally, and 3 trans-nationally. The earliest settlers were Austric, Dravidian followed by Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan, and Tai–Kadai people.[83] Forty-five languages are spoken by different communities, including three major language families: Austroasiatic (5), Sino-Tibetan (24) and Indo-European (12). Three of the spoken languages do not fall in these families. There is a high degree of bilingualism.

Religions

According to the 2011 census, 61.47% were Hindus, 34.22% were Muslims.[84][85] Christian minorities (3.7%) are found among the Scheduled Tribe and Castes population.[86] The Scheduled Tribe population in Assam is around 13%, of which Bodos account for 40%.[87] Other religions followed include Jainism (0.1%), Buddhism (0.2%), Sikhism (0.1%) and Animism (amongst Khamti, Phake, Aiton etc. communities). Many Hindus in Assam are followers of the Ekasarana Dharma sect of Hinduism, which gave rise to Namghar, designed to be simpler places of worship than traditional Hindu temples.

Out of 32 districts of Assam, 9 are Muslim majority according to the 2011 census of India. The districts are Dhubri, Goalpara, Barpeta, Morigaon, Nagaon, Karimganj, Hailakandi, Darrang and Bongaigaon.[88][89][90]

Languages

Assamese is the official language of the state. Additional official languages include Bengali and Bodo languages. Bodo in Bodoland Territorial Council and Bengali in the three districts of Barak Valley where Sylheti is most commonly spoken.[92]

According to the language census of 2011 in Assam, out of a total population of around 31 million, Assamese is spoken by around half that number: 15 million. Although the number of speakers is growing, the percentage of Assam's population who have it as a mother tongue has fallen slightly. The various Bengali dialects and closely related languages are spoken by around 9 million people in Assam, and the portion of the population that speaks these languages has grown slightly. Hindi is the third most-spoken language.

Traditionally, Assamese was the language of the common folk in the ancient Kamarupa kingdom and in the medieval kingdoms of Dimasa Kachari, Chutiya Kachari, Borahi Kachari, Ahom and Kamata kingdoms. Traces of the language are found in many poems by Luipa, Sarahapa, and others, in Charyapada (c. 7th–8th century CE). Modern dialects such as Kamrupi and Goalpariya are remnants of this language. Moreover, Assamese in its traditional form was used by the ethno-cultural groups in the region as lingua-franca, which spread during the stronger kingdoms and was required for economic integration. Localised forms of the language still exist in Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh.

Linguistically modern Assamese traces its roots to the version developed by the American Missionaries based on the local form used near Sivasagar (Xiwôxagôr) district. Assamese (Ôxômiya) is a rich language due to its hybrid nature and unique characteristics of pronunciation and softness. The presence of Voiceless velar fricative in Assamese makes it a unique among other similar Indo-Aryan languages.[93][94]

Bodo is an ancient language of Assam. Spatial distribution patterns of the ethno-cultural groups, cultural traits and the phenomenon of naming all the major rivers in the North East Region with Bodo-Kachari words (e.g. Dihing, Dibru, Dihong, D/Tista, and Dikrai) reveal that it was the most important language in ancient times. Bodo is now spoken largely in the Western Assam (BTAD). After years of neglect, now Bodo language is getting attention and its literature is developing. Other native languages of Tibeto-Burman origin and related to Bodo-Kachari are Deori, Mising, Karbi, Rabha, and Tiwa.

There are approximately 564,000 Nepali speakers spread all over the state forming about 2.12% of Assam's total population according to 2001 census.

There are speakers of Tai languages in Assam. A total of six Tai languages were spoken in Assam. Two are now extinct.[95]

Government and politics

Assam has Governor Jagdish Mukhi as the head of the state,[2] the unicameral Assam Legislative Assembly of 126 members, and a government led by the Chief Minister of Assam. The state is divided into five regional divisions.

On 19 May 2016, BJP under the leadership of Sarbananda Sonowal won the Assembly elections, thus forming the first BJP-led government in Assam.[96]

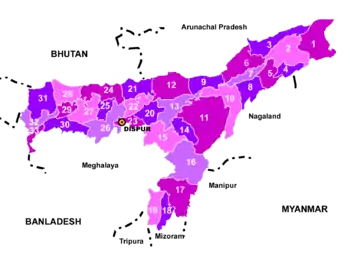

Administrative districts

The 33 administrative districts of Assam are delineated based on geographic features such as rivers, hills, and forests.

On 15 August 2015, five new districts were formed:[97][98]

- Part of Sonitpur became the Biswanath district (9 in the nearby map)

- Part of Sivasagar became the Charaideo district (4)

- Part of Nagaon became the Hojai district (14)

- Part of Dhubri became the South Salmara-Mankachar district (33)

- The Karbi Anglong district was divided into East (11) and West (15) districts

On 27 June 2016, an island in the Brahmaputra River was removed from the Jorhat district and declared the Majuli district, India's first district that is a river island.[99]

Subdivisions

The administrative districts are further subdivided into 54 "Subdivisions" or Mahakuma.[98] Every district is administered from a district headquarters with the office of the Deputy Commissioner, District Magistrate, Office of the District Panchayat and usually with a district court.

The local governance system is organised under the jila-parishad (District Panchayat) for a district, panchayat for group of or individual rural areas and under the urban local bodies for the towns and cities. There are now 2489 village panchayats covering 26247 villages in Assam.[100] The 'town-committee' or nagar-somiti for small towns, 'municipal board' or pouro-sobha for medium towns and municipal corporation or pouro-nigom for the cities consist of the urban local bodies.

For revenue purposes, the districts are divided into revenue circles and mouzas; for the development projects, the districts are divided into 219 'development-blocks' and for law and order these are divided into 206 police stations or thana.

Guwahati is the largest metropolitan area and urban conglomeration administered under the highest form of urban local body – Guwahati Municipal Corporation in Assam. The Corporation administers an area of 216.79 km2 (83.70 sq mi).[101] All other urban centres are managed under Municipal Boards.

A list of 9 oldest, classified and prominent, and constantly inhabited, recognised urban centres based on the earliest years of formation of the civic bodies, before the Indian independence of 1947 is tabulated below:

| Oldest recognised urban centres of Assam[102] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Centres | Civic Body | Year | Airport | Railway Station | Railway Junction | Road Networks | Category† | Notes |

| Guwahati | Guwahati Town Committee | 1853 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – III | More

Guwahati, the first township of Assam.[103] |

| Guwahati Municipal Board | 1873↑ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | ||

| Guwahati Municipal Corporation | 1974↑ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – I | More

Establishment of Guwahati Municipal Corporation.[104] | |

| Silchar | Silchar Municipal Board | 1922 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Silchar Municipality, 1922.[105] |

| Dibrugarh | Dibrugarh Municipal Board | 1873 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Dibrugarh, the second township of Assam.[106] |

| Goalpara | Goalpara Municipal Board | 1875 | No 1 | Yes | No 2 | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Goalpara Municipality, 1875.[107] |

| Dhubri | Dhubri Municipal Board | 1883 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Dhubri Municipality, 1883.[108] |

| Nagaon | Nagaon Municipal Board | 1893 | No 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Nagaon Municipality, 1893.[109] |

| Tezpur | Tezpur Municipal Board | 1894 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Tezpur Municipality, 1894.[110] |

| Jorhat | Jorhat Municipal Board | 1909 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Jorhat Municipality, 1909.[111] |

| Golaghat | Golaghat Municipal Board | 1920 | No 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Tier – II | More

Formation of Golaghat Municipality, 1920.[112] |

| †Tier – I: a big city with an urban conglomeration (in the true sense) administered by a Municipal corporation. Tier – II: a medium–sized city for an urban agglomeration administered by a Municipal Board. Tier – III: a small town, larger than a township with a sizeable human settlement. ↑Upgraded to the next highest form of civic body. | ||||||||

The state has three autonomous councils. Bodoland Autonomous Territorial Council, Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council and Dima Hasao Autonomous Council. The state has further more six statutory autonomous council – Tiwashong Autonomous Council, Jagiroad for ethnic Tiwa Kachari also known as Lalung, Rabha Hasong Autonomous Council, Dudhnoi for ethnic Rabha Kachari, Mishing Autonomous Council, Dhemaji for Mishings a Tani Tribe, Sonowal Kachari Autonomous Council, Dibrugarh, Thengal Kachari Autonomous Council, Titabar and Deori Autonomous Council, Lakhimpur for ethnic Deori Kachari.

Social Issues

Migration from Bangladesh

Assam has been a major site of migration since the Partition of the subcontinent, with the first wave being composed largely of Hindu Bengali refugees arrriving during and shortly after the establishment of India and Pakistan (current day Bangladesh was originally part of Pakistan, known as East Pakistan) in 1947-1951. Between 1946-1951, 274,455 Bengali Hindu refugees have arrived from what is now called Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) in Assam as permanent settlers.[113] The India-Pakistan War of 1965 and the accompanying communal rioting and massacres in Bangladesh produced another wave of largely Hindu migration from East Pakistan (Bangladesh) and a there was a third wave during and after the War of Independence that established Bangladeshi independence in 1971, with Assam home to around a thousand camps housing 347,555 refugees, which included persons of all backgrounds fleeing war.[114] Though the governments of India and Bangladesh made agreements for the repatriation of certain groups of refugees after the second and third waves, a large presence of refugees and other migrants and their descendants remained in the state.

Besides migration caused by displacement, there is also a large and continual unregulated movement between Assam and neighboring regions of Bangladesh with an exceptionally porous border. The situation is called a risk to Assam's as well as India's security.[115] The continual illegal entry of people into Assam, mostly from Bangladesh, has caused economic upheaval and social and political unrest.[116][117] During the Assam Movement (1979–1985), the All Assam Students Union (AASU) and others demanded that government stop the influx of immigrants and deport those who had already settled.[118] During this period, 855 people (the AASU says 860) died in various conflicts with migrants and police.[119][120] The 1983 Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, applied only to Assam, decreed that any person who entered the Assam after Bangladesh declared independence from Pakistan in 1971 and without authorisation or travel documents is to be considered a foreigner, with the decision on foreigner status to be carried out by designated tribunals. In 1985, the Indian Government and leaders of the agitation signed the Assam accord to settle the conflict.[118]

The 1991 census made the changing demographics of border districts more visible.[121][118] Since 2010, the Indian Government has undertaken the updating of the National Register of Citizens for Assam, and in 2018 the 32.2 million residents of Assam were subject to a review of their citizenship.[122] In August 2019, India released the names of the 2 million residents of Assam that had been determined to be non-citizens and whose names had therefore been struck off the Register of Citizens, depriving them of rights and making them subject to action, and potentially leaving some of them stateless, and the government has begun deporting non-citizens, while detaining 1,000 others that same year.[123][124][125]

In January 2019, the Assam's peasant organisation Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti (KMSS) claimed that there are around 20 lakh Hindu Bangladeshis in Assam who would become Indian citizens if the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill is passed. BJP, however claimed that only eight lakh Hindu Bangladeshis will get citizenship.[126][127][128] According to various sources, the total number of illegal Hindu Bangladeshis is hard to ascertain.[129][130] According to the census data, the number of Hindu immigrants have been largely exaggerated.[130]

In February 2020, the Assam Minority Development Board announced plans to segregate illegal Bangladeshi Muslim immigrants from the indigenous Muslims of the state, though some have expressed problems in identifying an indigenous Muslim person. According to the board, there are 1.3 crore Muslims in the state, of which 90 lakh are of Bangladeshi origin.[131][132]

Floods

In the rainy season every year, the Brahmaputra and other rivers overflow their banks and flood adjacent land. Flood waters wash away property including houses and livestock. Damage to crops and fields harms the agricultural sector. Bridges, railway tracks, and roads are also damaged, harming transportation and communication, and in some years requiring food to be air-dropped to isolated towns. Some deaths are attributed to the floods.[133][134]

Unemployment

Unemployment is a chronic problem in Assam. It is variously blamed on poor infrastructure, limited connectivity, and government policy;[135] on a "poor work culture";[136] on failure to advertise vacancies;[137] and on government hiring candidates from outside Assam.[138]

In 2020 a series of violent lynchings occurred in the region.

Education

School girls in the classroom, Lakhiganj High School, Assam

School girls in the classroom, Lakhiganj High School, Assam

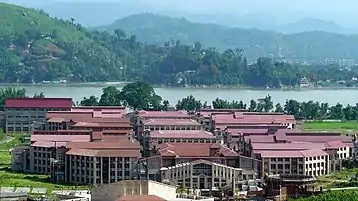

Academic complex of IIT Guwahati

Academic complex of IIT Guwahati

Assam schools are run by the Indian government, government of Assam or by private organisations. Medium of instruction is mainly in Assamese, English or Bengali. Most of the schools follow the state's examination board which is called the Secondary Education Board of Assam. Almost all private schools follow the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE) and Indian School Certificate (ISC) syllabuses.

Assamese language is the main medium in educational institutions but Bengali language is also taught as a major Indian language. In Guwahati and Digboi, many Jr. basic schools and Jr. high schools are Nepali linguistic and all the teachers are Nepali. Nepali is included by Assam State Secondary Board, Assam Higher Secondary Education Council and Gauhati University in their HSLC, higher secondary and graduation level respectively. In some junior basic and higher secondary schools and colleges, Nepali teachers and lecturers are appointed.

The capital, Dispur, contains institutions of higher education for students of the north-eastern region. Cotton College, Guwahati, dates back to the 19th century. Assam has several institutions for tertiary education and research.

Universities, colleges and institutions include:

Universities

- Assam University

- Assam Agricultural University, Jorhat

- Assam Don Bosco University,[139]

- Assam down town University,[140]

- Assam Rajiv Gandhi University of Cooperative Management, (ARGUCOM), Sivasagar

- Assam Science and Technology University,[141] Guwahati

- Assam Women's University,[142] Jorhat

- Bodoland University,[143] Kokrajhar

- Cotton University, Guwahati

- Dibrugarh University,[144] Dibrugarh

- Gauhati University,[145] Guwahati

- Kaziranga University,[146] Jorhat

- Krishnaguru Adhyatmik Vishvavidyalaya

- Krishna Kanta Handique State Open University

- Kumar Bhaskar Varma Sanskrit and Ancient Studies University

- Mahapurusha Srimanta Sankaradeva Viswavidyalaya

- National Law University and Judicial Academy, Assam[147]

- Royal Global University

- Srimanta Sankaradeva University of Health Sciences

- Tezpur University,[148]Tezpur

Medical colleges

Engineering and technological colleges

- Indian Institute of Information Technology, Guwahati

- National Institute of Technology, Silchar,[149]

- Assam Engineering College in Guwahati,

- Assam Science and Technology University

- Bineswar Brahma Engineering College, Kokrajhar

- Central Institute of Technology, Kokrajhar,

- Girijananda Chowdhury Institute of Management and Technology, Guwahati[150]

- Girijananda Chowdhury Institute of Management and Technology, Tezpur

- Indian Institute of Technology in Guwahati,

- Institute of Engineering and Technology, Dibrugarh University

- Institute of Science and Technology, Guwahati University

- Jorhat Engineering College in Jorhat.

- Jorhat Institute of Science & Technology, Jorhat

- NETES Institute of Technology & Science Mirza,

- Barak Valley Engineering College Nirala Karimganj

- Golaghat Engineering College Golaghat

Research institutes present in the state include National Research Centre on Pig, (ICAR) in Guwahati,[151]

Economy

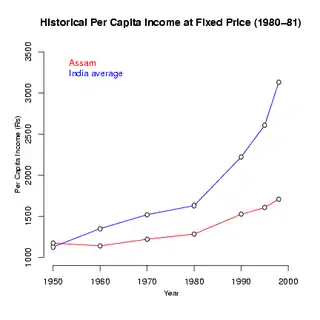

Assam's economy is based on agriculture and oil. Assam produces more than half of India's tea.[152] The Assam-Arakan basin holds about a quarter of the country's oil reserves, and produces about 12% of its total petroleum.[153] According to the recent estimates,[154] Assam's per capita GDP is ₹6,157 at constant prices (1993–94) and ₹10,198 at current prices; almost 40% lower than that in India.[155] According to the recent estimates,[154] per capita income in Assam has reached ₹6756 (1993–94 constant prices) in 2004–05, which is still much lower than India's.

Tea plantations

Macro-economy

The economy of Assam today represents a unique juxtaposition of backwardness amidst plenty.[156] Despite its rich natural resources, and supplying of up to 25% of India's petroleum needs, Assam's growth rate has not kept pace with that of India; the difference has increased rapidly since the 1970s.[157] The Indian economy grew at 6% per annum over the period of 1981 to 2000; the growth rate of Assam was only 3.3%.[158] In the Sixth Plan period, Assam experienced a negative growth rate of 3.78% when India's was positive at 6%.[157] In the post-liberalised era (after 1991), the difference widened further.

According to recent analysis, Assam's economy is showing signs of improvement. In 2001–02, the economy grew (at 1993–94 constant prices) at 4.5%, falling to 3.4% in the next financial year.[159] During 2003–04 and 2004–05, the economy grew (at 1993–94 constant prices) at 5.5% and 5.3% respectively.[159] The advanced estimates placed the growth rate for 2005–06 at above 6%.[154] Assam's GDP in 2004 is estimated at $13 billion in current prices. Sectoral analysis again exhibits a dismal picture. The average annual growth rate of agriculture, which was 2.6% per annum over the 1980s, has fallen to 1.6% in the 1990s.[160] The manufacturing sector showed some improvement in the 1990s with a growth rate of 3.4% per annum than 2.4% in the 1980s.[160] For the past five decades, the tertiary sector has registered the highest growth rates of the other sectors, which even has slowed down in the 1990s than in the 1980s.[160]

Employment

Unemployment is one of the major problems in Assam. This problem can be attributed to overpopulation and a faulty education system. Every year, large numbers of students obtain higher academic degrees but because of non-availability of proportional vacancies, most of these students remain unemployed.[161][162] A number of employers hire over-qualified or efficient, but under-certified, candidates, or candidates with narrowly defined qualifications. The problem is exacerbated by the growth in the number of technical institutes in Assam which increases the unemployed community of the State. Many job-seekers are eligible for jobs in sectors like railways and Oil India but do not get these jobs because of the appointment of candidates from outside of Assam to these posts. The reluctance on the part of the departments concerned to advertise vacancies in vernacular language has also made matters worse for local unemployed youths particularly for the job-seekers of Grade C and D vacancies.[163][164]

Reduction of the unemployed has been threatened by illegal immigration from Bangladesh. This has increased the workforce without a commensurate increase in jobs. Immigrants compete with local workers for jobs at lower wages, particularly in construction, domestics, Rickshaw-pullers, and vegetable sellers.[165][166] The government has been identifying (via NRC) and deporting illegal immigrants. Continued immigration is exceeding deportation.[167][168]

Agriculture

In Assam among all the productive sectors, agriculture makes the highest contribution to its domestic sectors, accounting for more than a third of Assam's income and employs 69% of workforce.[169] Assam's biggest contribution to the world is Assam tea. It has its own variety, Camellia sinensis var. assamica. The state produces rice, rapeseed, mustard seed, jute, potato, sweet potato, banana, papaya, areca nut, sugarcane and turmeric.

Assam's agriculture is yet to experience modernisation in a real sense. With implications for food security, per capita food grain production has declined in the past five decades.[170] Productivity has increased marginally, but is still low compared to highly productive regions. For instance, the yield of rice (a staple food of Assam) was just 1531 kg per hectare against India's 1927 kg per hectare in 2000–01[170] (which itself is much lower than Egypt's 9283, US's 7279, South Korea's 6838, Japan's 6635 and China's 6131 kg per hectare in 2001[171]). On the other hand, after having strong domestic demand, and with 1.5 million hectares of inland water bodies, numerous rivers and 165 varieties of fishes,[172] fishing is still in its traditional form and production is not self-sufficient.[173]

Floods in Assam greatly affect the farmers and the families dependent on agriculture because of large-scale damage of agricultural fields and crops by flood water.[57][58] Every year, flooding from the Brahmaputra and other rivers deluges places in Assam. The water levels of the rivers rise because of rainfall resulting in the rivers overflowing their banks and engulfing nearby areas. Apart from houses and livestock being washed away by flood water, bridges, railway tracks and roads are also damaged by the calamity, which causes communication breakdown in many places. Fatalities are also caused by the natural disaster in many places of the state.[174][175]

Industry

Handlooming and handicraft continue.

Assam's proximity to some neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan, benefits its trade. The major Border checkpoints through which border trade flows to Bangladesh from Assam are : Sutarkandi (Karimganj), Dhubri, Mankachar (Dhubri) and Golokanj. To facilitate border trade with Bangladesh, Border Trade Centres have been developed at Sutarkandi and Mankachar. It has been proposed in the 11th five-year plan to set up two more Border Trade Center, one at Ledo connecting China and other at Darrang connecting Bhutan. There are several Land Custom Stations (LCS) in the state bordering Bangladesh and Bhutan to facilitate border trade.[176]

The government of India has identified some thrust areas for industrial development of Assam:[177]

- Petroleum and natural gas-based industries

- Industries based on locally available minerals

- Processing of plantation crops

- Food processing industries

- Agri-Horticulture products

- Herbal products

- Biotech products

- Pharmaceuticals

- Chemical and plastic-based industries

- Export oriented industries

- Electronic and IT base industries including services sector

- Paper making industries

- Textiles and sericulture

- Engineering industries

- Cane and bamboo-based industries

- Other handicrafts industry

Although, the region in the eastern periphery of India is landlocked and is linked to the mainland by the narrow Siliguri Corridor (or the Chicken's Neck) improved transport infrastructure in all the three modes – rail, road and air – and developing urban infrastructure in the cities and towns of Assam are giving a boost to the entire industrial scene. The Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport at Guwahati, with international flights to Bangkok and Singapore offered by Druk Air of Bhutan, was the 12th busiest airport of India in 2012.[178] The cities of Guwahati[179][180] in the west and Dibrugarh[181][182] in the east with good rail,[183][184] road and air connectivity are the two important nerve centres of Assam, to be selected by Asian Development Bank for providing $200 million for improvement of urban infrastructure.[185][186]

Assam is a producer of crude oil and it accounts for about 15% of India's crude output,[187] exploited by the Assam Oil Company Ltd.,[188] and natural gas in India and is the second place in the world (after Titusville in the United States) where petroleum was discovered. Asia's first successful mechanically drilled oil well was drilled in Makum way back in 1867. Most of the oilfields are located in the Eastern Assam region. Assam has four oil refineries in Digboi (Asia's first and world's second refinery), Guwahati, Bongaigaon and Numaligarh and with a total capacity of 7 million metric tonnes (7.7 million short tons) per annum. Asia's first refinery was set up at Digboi and discoverer of Digboi oilfield was the Assam Railways & Trading Company Limited (AR&T Co. Ltd.), a registered company of London in 1881.[189] One of the biggest public sector oil company of the country Oil India Ltd. has its plant and headquarters at Duliajan.

There are several other industries, including a chemical fertiliser plant at Namrup, petrochemical industries in Namrup and Bongaigaon, paper mills at Jagiroad, Hindustan Paper Corporation Ltd. Township Area Panchgram and Jogighopa, sugar mills in Barua Bamun Gaon, Chargola, Kampur, cement plants in Bokajan and Badarpur, and a cosmetics plant of Hindustan Unilever (HUL) at Doom Dooma. Moreover, there are other industries such as jute mill, textile and yarn mills, Assam silk, and silk mills. Many of these industries are facing losses and closure due to lack of infrastructure and improper management practices.[190]

Tourism

Wildlife, cultural, and historical destinations have attracted visitors.

Culture

Assamese Culture is traditionally a hybrid one developed due to assimilation of ethno-cultural groups of Austric, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman and Tai origin in the past. Therefore, both local elements or the local elements in Sanskritised forms are distinctly found.[191] The major milestones in the evolution of Assamese culture are:

- Assimilation in the Kamarupa Kingdom for almost 700 years (under the Varmans for 300 years, Salastambhas and Palas for each 200 years).[17]

- Establishment of the Chutiya dynasty in the 12th century in eastern Assam and assimilation for next 400 years.[17]

- Establishment of the Ahom dynasty in the 13th century CE and assimilation for next 600 years.[17]

- Assimilation in the Koch Kingdom (15th–16th century CE) of western Assam and Kachari Kingdom (12th–18th century CE) of central and southern Assam.[17]

- Vaishnava Movement led by Srimanta Shankardeva (Xongkordeu) and its contribution and cultural changes. The Vaishanava Movement, the 15th century religio-cultural movement under the leadership of Srimanta Sankardeva (Sonkordeu) and his disciples have provided another dimension to Assamese culture. A renewed Hinduisation in local forms took place, which was initially greatly supported by the Koch and later by the Ahom Kingdoms. The resultant social institutions such as namghar and sattra (the Vaishnav Monasteries) have become part of the Assamese way of life. The movement contributed greatly towards language, literature, and performing and fine arts.

The modern culture has been influenced by events in the British and the post-British era. The language was standardised by American Baptist Missionaries such as Nathan Brown, Dr. Miles Bronson and local pundits such as Hemchandra Barua with the form available in the Sibsagar (Sivasagar) District (the ex-nerve centre of the Ahom Kingdom).

Increasing efforts of standardisation in the 20th century alienated the localised forms present in different areas and with the less-assimilated ethno-cultural groups (many source-cultures). However, Assamese culture in its hybrid form and nature is one of the richest, still developing and in true sense is a 'cultural system' with sub-systems. Many source-cultures of the Assamese cultural-system are still surviving either as sub-systems or as sister entities, e.g. the; Bodo or Karbi or Mishing. It is important to keep the broader system closer to its roots and at the same time focus on development of the sub-systems.

Some of the common and unique cultural traits in the region are peoples' respect towards areca-nut and betel leaves, symbolic (gamosa, arnai, etc.), traditional silk garments (e.g. mekhela chador, traditional dress of Assamese women) and towards forefathers and elderly. Moreover, great hospitality and bamboo culture are common.

Symbols

Symbolism is an ancient cultural practice in Assam and is still a very important part of the Assamese way of life. Various elements are used to represent beliefs, feelings, pride, identity, etc. Tamulpan, Xorai and Gamosa are three important symbolic elements in Assamese culture. Tamulpan (the areca nut and betel leaves) or guapan (gua from kwa) are considered along with the Gamosa (a typical woven cotton or silk cloth with embroidery) as the offers of devotion, respect and friendship. The Tamulpan-tradition is an ancient one and is being followed since time-immemorial with roots in the aboriginal Austric culture. Xorai is a traditionally manufactured bell-metal article of great respect and is used as a container-medium while performing respectful offers. Moreover, symbolically many ethno-cultural groups use specific clothes to portray respect and pride.

There were many other symbolic elements and designs, but are now only found in literature, art, sculpture, architecture, etc. or in use today for only religious purposes. The typical designs of Assamese-lion, dragon, and flying-lion were used for symbolising various purposes and occasions. The archaeological sites such as the Madan Kamdev (c. 9th–10th centuries CE) exhibits mass-scale use of lions, dragon-lions and many other figures of demons to show case power and prosperity. The Vaishnava monasteries and many other architectural sites of the late medieval period display the use of lions and dragons for symbolic effects.

Festivals and traditions

There are diversified important traditional festivals in Assam. Bihu is the most important and common and celebrated all over Assam. It is the Assamese new year celebrated in April of the Gregorian calendar. Christmas is observed with great merriment by Christians of various denominations, including Catholics and Protestants, throughout Assam. Durga Puja, a festival introduced and popularised by Bengalis, is widely celebrated across the state. Muslims celebrate two Eids (Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha) with much eagerness all over Assam.

Bihu is a series of three prominent festivals. Primarily a non-religious festival celebrated to mark the seasons and the significant points of a cultivator's life over a yearly cycle. Three Bihus, rongali or bohag, celebrated with the coming of spring and the beginning of the sowing season; kongali or kati, the barren bihu when the fields are lush but the barns are empty; and the bhogali or magh, the thanksgiving when the crops have been harvested and the barns are full. Bihu songs and Bihu dance are associated to rongali bihu. The day before the each bihu is known as 'uruka'. The first day of 'rongali bihu' is called 'Goru bihu' (the bihu of the cows), when the cows are taken to the nearby rivers or ponds to be bathed with special care. In recent times the form and nature of celebration has changed with the growth of urban centres.

Bwisagu is one of the popular seasonal festivals of the Bodos. Bwisagu start of the new year or age. Baisagu is a Boro word which originated from the word "Baisa" which means year or age, and "Agu" that means starting or start.

Beshoma is a festival of Deshi people.[192] It is a celebration of sowing crop. The Beshoma starts on the last day of Chaitra and goes on till the sixth of Baisakh. With varying locations it is also called Bishma or Chait-Boishne.[193]

Bushu Dima or simply Bushu is a major harvest festival of the Dimasa people. This festival is celebrated during the end of January. Officially 27 January has been declared as the day of Bushu Dima festival. The Dimasa people celebrate their festival by playing musical instruments- khram (a type of drum), muri (a kind of huge long flute). The people dances to the different tunes called "murithai" and each dance has got its name, the prominent being the "Baidima" There are three types of Bushu celebrated among the Dimasas Jidap, Surem and Hangsou.

Chavang Kut is a post harvesting festival of the Kuki people. The festival is celebrated on the first day of November every year. Hence, this particular day has been officially declared as a Restricted Holiday by the Assam government. In the past, the celebration was primarily important in the religio-cultural sense. The rhythmic movements of the dances in the festival were inspired by animals, agricultural techniques and showed their relationship with ecology. Today, the celebration witnesses the shifting of stages and is revamped to suit new contexts and interpretations. The traditional dances which form the core of the festival is now performed in out-of-village settings and are staged in a secular public sphere. In Assam, the Kukis mainly reside in the two autonomous districts of Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong.

Moreover, there are other important traditional festivals being celebrated every year on different occasions at different places. Many of these are celebrated by different ethno-cultural groups (sub and sister cultures). Some of these are:

- Me-Dam-Me-Phi

- Ali-Aye-Ligang

- Rongker

- Kherai

- Garja

- Bisu (Deori)

- Awnkham Gwrlwi Janai

- Chojun/Swarak

- Deusi Bhailo ( Traditional Nepalese songs that are sung during the festival of light " Dipavali and also called "Tihar" )

- Sokk-erroi

- Hacha-kekan

- Hapsa Hatarnai

- Porag

- Bathow

- Wangala

- Bohuwa dance

Other few yearly celebrations are Doul Utsav of Barpeta, Brahmaputra Beach Festival, Guwahati, Kaziranga Elephant Festival, Kaziranga and Dehing Patkai Festival, Lekhapani, Karbi Youth Festival of Diphu and International Jatinga Festival, Jatinga can not be forgotten. Few yearly Mela's like Jonbeel Mela, began in the 15th century by the Ahom Kings, Ambubachi Mela, Guwahati etc.

Lachit Divas' is celebrated to promote the ideals of Lachit Borphukan – the legendary general of Assam's history. Sarbananda Sonowal, the chief minister of Assam took part in the Lachit Divas celebration at the statue of Lachit Borphukan at Brahmaputra riverfront on 24 November 2017. He said, the first countrywide celebration of 'Lachit Divas' would take place in New Delhi followed by state capitals such as Hyderabad, Bangalore and Kolkata in a phased manner.

Music, dance, and drama

Bodo dance Bagurumba

Bodo dance Bagurumba "Adivasi"-Jhumair dance

"Adivasi"-Jhumair dance Nagara

Nagara

Assamese youth performing Bihu Dance

Assamese youth performing Bihu Dance.JPG.webp) Statute of Bishnu Prasad Rabha, Jyoti Prasad Agarwala and Phani Sarma at District Library, Guwahati.

Statute of Bishnu Prasad Rabha, Jyoti Prasad Agarwala and Phani Sarma at District Library, Guwahati.

Performing arts include: Ankia Naat (Onkeeya Naat), a traditional Vaishnav dance-drama (Bhaona) popular since the 15th century CE. It makes use of large masks of gods, goddesses, demons and animals and in between the plays a Sutradhar (Xutrodhar) continues to narrate the story.

Besides Bihu dance and Huchory performed during the Bohag Bihu, dance forms of tribal minorities such as; Kushan nritra of Rajbongshi's, Bagurumba and Bordoicikhla dance of Bodos, Mishing Bihu, Banjar Kekan performed during Chomangkan by Karbis, Jhumair of Tea-garden community are some of the major folk dances.[194] Sattriya (Sotriya) dance related to Vaishnav tradition is a classical form of dance. Moreover, there are several other age-old dance-forms such as Barpeta's Bhortal Nritya, Deodhani Nritya, Ojapali, Beula Dance, Ka Shad Inglong Kardom, Nimso Kerung, etc. The tradition of modern moving theatres is typical of Assam with immense popularity of many Mobile theatre groups such as Kohinoor, Sankardev, Abahan, Bhagyadevi, Hengul, Brindabon, Itihas etc.

The indigenous folk music has influenced the growth of a modern idiom, that finds expression in the music of artists like Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, Bishnuprasad Rabha, Parvati Prasad Baruwa, Bhupen Hazarika, Pratima Barua Pandey, Anima Choudhury, Luit Konwar Rudra Baruah, Jayanta Hazarika, Khagen Mahanta, Dipali Barthakur, Ganashilpi Dilip Sarma, Sudakshina Sarma among many others. Among the new generation, Zubeen Garg, Jitul Sonowal, Angaraag Mahanta and Joi Barua. There is an award given in the honour of Bishnu Prasad Rabha for achievements in the cultural/music world of Assam by the state government.

Cuisine

Typically, an Assamese meal consists of many things such as bhat (rice) with dayl/ daly (lentils), masor jool (fish stew), mangxô (meat stew) and stir fried greens or herbs and vegetables.

The two main characteristics of a traditional meal in Assam are khar (an Alkali, named after its main ingredient) and tenga (Preparations bearing a characteristically rich and tangy flavour). Khorika is the smoked or fire grilled meat eaten with meals. Commonly consumed varieties of meat include Mutton, fowl, duck/goose, fish, pigeon, pork and beef (among Muslim and Christian indigenous Assamese ethnic groups). Grasshoppers, locusts, silkworms, snails, eels, wild fowl, squab and other birds, venison are also eaten, albeit in moderation.

Khorisa (fermented bamboo shoots) are used at times to flavour curries while they can also be preserved and made into pickles. Koldil (banana flower) and squash are also used in popular culinary preparations.[195]

A variety of different rice cultivars are grown and consumed in different ways, viz., roasted, ground, boiled or just soaked.

Fish curries made of free range wild fish as well as Bôralí, rôu, illish, or sitôl are the most popular.

Another favourite combination is luchi (fried flatbread), a curry which can be vegetarian or non-vegetarian.

Many indigenous Assamese communities households still continue to brew their traditional alcoholic beverages; examples include: Laupani, Xaaj, Paniyo, Jou, Joumai, Hor, Apang, etc. Such beverages are served during traditional festivities. Declining them is considered socially offensive.

The food is often served in bell metal dishes and platters like Kanhi, Maihang and so on.

Literature

Assamese literature dates back to the composition of Charyapada, and later on works like Saptakanda Ramayana by Madhava Kandali, which is the first translation of the Ramayana into an Indo-Aryan language, contributed to Assamese literature.[197][198][199] Sankardeva's Borgeet, Ankia Naat, Bhaona and Satra tradition backed the 15th-16th century Assamese literature.[200][201][202][203] Written during the Reign of Ahoms, the Buranjis are notable literary works which are prominently historical manuscripts.[204] Most literary works are written in Assamese although other local language such as Bodo and Dimasa are also represented. In the 19th and 20th century, Assamese and other literature was modernised by authors including Lakshminath Bezbaroa, Birinchi Kumar Barua, Hem Barua, Dr. Mamoni Raisom Goswami, Bhabendra Nath Saikia, Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya, Hiren Bhattacharyya, Homen Borgohain, Bhabananda Deka, Rebati Mohan Dutta Choudhury, Mahim Bora, Lil Bahadur Chettri, Syed Abdul Malik, Surendranath Medhi, Hiren Gohain etc.

Fine arts

The archaic Mauryan Stupas discovered in and around Goalpara district are the earliest examples (c. 300 BCE to c. 100 CE) of ancient art and architectural works. The remains discovered in Daparvatiya (Doporboteeya) archaeological site with a beautiful doorframe in Tezpur are identified as the best examples of artwork in ancient Assam with influence of Sarnath School of Art of the late Gupta period.

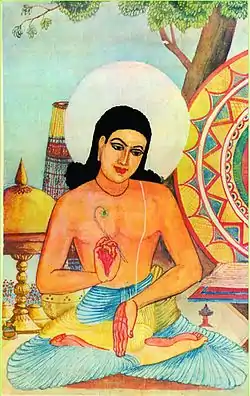

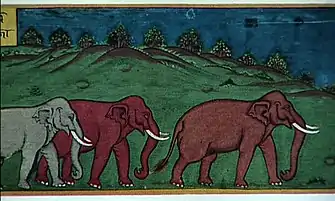

Painting is an ancient tradition of Assam. Xuanzang (7th century CE) mentions that among the Kamarupa king Bhaskaravarma's gifts to Harshavardhana there were paintings and painted objects, some of which were on Assamese silk. Many of the manuscripts such as Hastividyarnava (A Treatise on Elephants), the Chitra Bhagawata and in the Gita Govinda from the Middle Ages bear excellent examples of traditional paintings.

Traditional crafts

Assam has a rich tradition of crafts, Cane and bamboo craft, bell metal and brass craft, silk and cotton weaving, toy and mask making, pottery and terracotta work, wood craft, jewellery making, and musical instruments making have remained as major traditions.[205]

Cane and bamboo craft provide the most commonly used utilities in daily life, ranging from household utilities, weaving accessories, fishing accessories, furniture, musical instruments, construction materials, etc. Utilities and symbolic articles such as Sorai and Bota made from bell metal and brass are found in every Assamese household.[206][207] Hajo and Sarthebari (Sorthebaary) are the most important centres of traditional bell-metal and brass crafts. Assam is the home of several types of silks, the most prestigious are: Muga – the natural golden silk, Pat – a creamy-bright-silver coloured silk and Eri – a variety used for manufacturing warm clothes for winter. Apart from Sualkuchi (Xualkuchi), the centre for the traditional silk industry, in almost every parts of the Brahmaputra Valley, rural households produce silk and silk garments with excellent embroidery designs. Moreover, various ethno-cultural groups in Assam make different types of cotton garments with unique embroidery designs and wonderful colour combinations.

Moreover, Assam possesses unique crafts of toy and mask making mostly concentrated in the Vaishnav Monasteries, pottery and terracotta work in western Assam districts and wood craft, iron craft, jewellery, etc. in many places across the region.

Citra Bhagavata illustration

Citra Bhagavata illustration A folio from the Hastividyarnava manuscript

A folio from the Hastividyarnava manuscript

A page of manuscript painting from Assam; The medieval painters used locally manufactured painting materials such as the colours of hangool and haital and papers manufactured from aloewood bark  Bell metal made sorai and sophura are important parts of culture

Bell metal made sorai and sophura are important parts of culture Assam Kahor (Bell metal) Kahi

Assam Kahor (Bell metal) Kahi

Media

Print media include Assamese dailies Amar Asom, Asomiya Khobor, Asomiya Pratidin, Dainik Agradoot, Dainik Janambhumi, Dainik Asam, Gana Adhikar, Janasadharan and Niyomiya Barta. Asom Bani, Sadin and Bhal Khabar are Assamese weekly newspapers. English dailies of Assam include The Assam Tribune, The Sentinel, The Telegraph, The Times of India,The North East Times, Eastern Chronicle and The Hills Times. Thekar, in the Karbi language has the largest circulation of any daily from Karbi Anglong district. Bodosa has the highest circulation of any Bodo daily from BTC. Dainik Jugasankha is a Bengali daily with editions from Dibrugarh, Guwahati, Silchar and Kolkata. Dainik Samayik Prasanga, Dainik Prantojyoti, Dainik Janakantha and Nababarta Prasanga are other prominent Bengali dailies published in the Barak Valley towns of Karimganj and Silchar. Hindi dailies include Purvanchal Prahari, Pratah Khabar and Dainik Purvoday.

Broadcasting stations of All India Radio have been established in five big cities: Dibrugarh, Guwahati, Kokrajhar, Silchar and Tezpur. Local news and music are the main priority for that station. Assam has three public service broadcasting service stations at Dibrugarh, Guwahati and Silchar. Guwahati is the headquarters of a number of electronic medias like Assam Talks, DY 365, News Live, News 18 Assam/North-East, Prag News and Pratidin Time.

Notable people

- Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, playwright, songwriter, poet and film maker

- Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, 5th President of India

- Talimeren Ao, India football captain.

- Jahnu Barua, film maker

- Kanaklata Barua, independence activist

- Bhogeswar Baruah, athlete and coach, Asian Games gold medallist, Arjuna awardee

- Uddhab Bharali, inventor, innovator

- Jatin Bora, actor

- Gopinath Bordoloi, independence activist, first chief minister of Assam

- Homen Borgohain, writer and journalist

- Anwara Taimur, first women Chief Minister of Assam

- Lachit Borphukan, commander of Ahom Kingdom

- Parineeta Borthakur, singer, actress

- Atan Burhagohain, one of the most influential Burhagohains of Ahom Kingdom

- Moinul Hoque Choudhury, Politician and former Central minister of Industrial Development

- Hima Das, athlete and Asian Games gold medallist

- Rima Das, film director and producer

- Zubeen Garg, musician, actor, director, producer and singer

- Akhil Gogoi, Social Activist

- Ranjan Gogoi, former Chief Justice of India, BJP government nominated MP to Rajyasabha

- Tarun Gogoi, former Chief Minister of Assam

- Hiren Gohain, social scientist

- Arnab Goswami, journalist and editor-in-chief of Republic Bharat TV

- Jitendra Nath Goswami, chief scientist of ISRO's Chandrayaan-1

- Mamoni Raisom Goswami, professor, writer, activist

- Nipon Goswami, actor

- Aideu Handique, first actress in Assamese cinema, one of the first actresses in India to play a leading role

- Bhupen Hazarika, musician, lyricist, singer and poet

- Adil Hussain, actor

- Joymoti Konwari, Tai-Ahom princess

- Madhavdev, disciple of Sankardev, preceptor of Ekasarana Dharma

- Monalisa Baruah Mehta, table tennis player, Arjuna awardee

- Halicharan Narzary, footballer, plays in India national team

- Papon, singer and musician

- Riyan Parag, Cricketer

- Jadav Payeng, environmentalist and naturalist

- Bishnu Prasad Rabha, musician, songwriter, lyricist

- Vinit Rai footballer, plays in Indian national team

- Srimanta Sankardev, saint-scholar, poet, playwright, social-religious reformer and founder of Ekasarana Dharma

- Sukaphaa, founder of the Ahom dynasty

- Jayanta Talukdar, archer, Asian games medallist, Arjuna awardee

- Shiva Thapa, boxer, Asian Games gold medallist, Arjuna awardee

See also

India portal

India portal- Outline of Assam – comprehensive topic guide listing articles about Assam.

- East Bengali refugees

Notes

- Steinberg, S. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book 1964–65: The One-Volume ENCYCLOPAEDIA of all nations. Springer. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-230-27093-0.

- "Jagdish Mukhi: Few facts about Assam's new Governor". The New Indian Express. 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "MOSPI Gross State Domestic Product". Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 52nd report (July 2014 to June 2015)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 58–59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "Govt withdraws Assamese as official language from Barak valley". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) Accord". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- "Assam Legislative Assembly - History". Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Assam". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Assam". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Here is India's oil story". The Financial Express. 3 May 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Besatia in the Schoff translation and also sometimes used by Ptolemy, they are a people similar to Kirradai and they lived in the region between "Assam and Sichuan" (Casson 1989, pp. 241–243)

- "The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea (last quarter of the first century A.D) and Ptolemy's Geography (middle of the second century A.D) appear to call the land including Assam Kirrhadia after its Kirata population." (Sircar 1990:60–61)

- "Prior to the thirteenth century the present region was called Kāmarūpa or, alternatively, Prāgjyotiṣapur", Lahiri, Nayanjot., Pre-Ahom Assam (Delhi 1991) p. 14

- "Ahoms also gave Assam and its language their name (Ahom and the modern ɒχɒm 'Assam' come from an attested earlier form asam, acam, probably from a Burmese corruption of the word Shan/Shyam, cf. Siam: Kakati 1962; 1-4)." (Masica 1993, p. 50)