Raymond Hood

Raymond Mathewson Hood (March 29, 1881 – August 14, 1934) was an American architect who worked in the Art Deco style.

Raymond Hood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 March 1881 |

| Died | 14 August 1934 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Brown University, MIT, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Tribune Tower, Comcast Building, New York Daily News Building |

Life and career

Hood was born in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and attended Brown University before enrolling at MIT. As a post-graduate, Hood worked as a draftsman at the architecture firm Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson in Boston.

He was accepted into the École des Beaux-Arts in 1911 and earned a degree.[1]

In 1922, New York architect John Mead Howells, who had met him at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, invited Hood to become his partner in the Chicago Tribune building competition in which Howells had been invited to compete. The design submitted by Howells and Hood won the competition, and Hood, 41, become touted as one of New York's best architects.[2]

Hood did not consider himself an artist, but saw himself as "manufacturing shelter",[2] writing:

There has been entirely too much talk about the collaboration of architect, painter and sculptor; nowadays, the collaborators are the architects, the engineer, and the plumber. ... Buildings are constructed for certain purposes, and the buildings of today are more practical, from the standpoint of the man who is in them than the older buildings. ... We are considering effort and convenience much more than appearance or effect.[3]

Hood's design theory was aligned with that of the Bauhaus, in that he valued utility as beauty:

Beauty is utility, developed in a manner to which the eye is accustomed by habit, in so far as this development does not detract from its quality of usefulness.[4]

Despite this paen to utility, Hood's designs featured non-utilitarian aspects such as roof gardens, polychromy, and Art Deco ornamentation. As much as Hood might insist that his designs were largely determined by the practicalities of zoning laws and the restraints of economics, each of his major buildings were different enough to suggest that Hood's design artistry was a significant factor in the final result.[2]

While a student at the École des Beaux-Arts, Hood met John Mead Howells, with whom he later partnered. Hood frequently employed architectural sculptor Rene Paul Chambellan both for architectural sculptures for his building and to make plasticine models of his projects. Hood is believed to have coined the term "Architecture of the Night" in a 1930 pamphlet published by General Electric.[5]

Hood died at age 53 and was interred at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York.

In fiction

Frank Heynick[6] has argued from a study of the journal notes of Ayn Rand made in the late 1930s and of incidents in her 1943 novel The Fountainhead, that Raymond Hood's career and works provided fodder for her fictional architect Peter Keating. This major figure in The Fountainhead epitomized the "second-hander" who – in stark opposition to the uncompromising and innovative hero of the novel, Howard Roark, and exemplified in real life by Frank Lloyd Wright, whom Rand idolized – adapts the classicist and historicist Old World architectural styles to the new American medium of the skyscraper, and then goes on to adopt modernism as soon as this becomes safely fashionable. Certain specific incidents in the fictional Keating's career are pointed to by Heynick as having been drawn from Hood's real-life career, such as their both suddenly gaining national fame by winning the highly publicized skyscraper contest for a media corporation in the early 1920s with a design in the historicist style, and their both heading the committee for a "modernistic" World's Fair in the 1930s from which the hero architect (Howard Roark in the novel, Frank Lloyd Wright in real-life) was excluded.[6]

Nevertheless, with regard to Rockefeller Center, of which Hood was the chief designer, Rand, despite her earlier negative comments in her journals, was subsequently cited as having some good words for the RCA Building. More intriguingly, as Heynick points out, Rand is quoted in a 1943 newspaper interview as referring to Hood's McGraw-Hill Building as the most beautiful in New York, thus, apparently, seeing Hood in a different light. This, Heynick argues, was justly so. Rand's creating of the negative fictional character of Peter Keating required her to draw exclusively upon the negative aspects of Hood's career as she perceived it. But particularly with reference to the Art Deco mode – a style which goes unmentioned in Rand's novel – Hood in fact showed his creative versatility in designing two Deco skyscrapers so radically distinct from one another as the RCA Building and the McGraw-Hill Building.[6]

Selected works

- Mori restaurant, Manhattan, New York City, 1920; Hood designed a new facade for a restaurant that had opened in 1883[7]

- Tribune Tower, Chicago, Illinois, 1924

- American Radiator Building, also known as the American Standard Building, Manhattan, New York City, 1924

- Ocean Forest Country Club, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, 1926-1927

- Ideal House, London, 1929

- Daily News Building Manhattan, New York City, 1929

- Masonic Temple, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1930

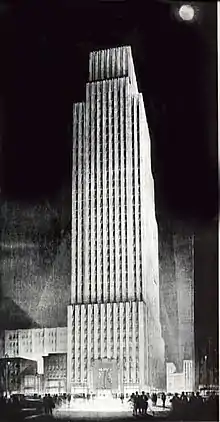

- Rockefeller Center, Manhattan, New York City, 1933-37, where Hood was a senior architect on the Associated Architects involved in the construction of Rockefeller Center

- McGraw-Hill Building, Manhattan, New York City, 1931

Mori Restaurant

Mori Restaurant American Radiator Building

American Radiator Building Ocean Forest Country Club

Ocean Forest Country Club Daily News Building

Daily News Building.jpg.webp) Scranton Cultural Center

Scranton Cultural Center Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center Mcgraw Hill Building

Mcgraw Hill Building

References

Notes

- Baughman, Judith S., ed. (1996). American Decades: 1920 - 1929. New York: Gale Research. pp. 180–1. ISBN 9780810357242.

- Robins, Anthony W. (September 11, 1979). "McGraw-Hill Building Designation Report" (PDF). New York Landmarks Preservation Commission.

- Woolf, S. J. "An Architect Hails the Rule of Reason - Design that is grounded in material and function ill make buildings more beautiful, says Raymond Hood" New York Times Magazine (November 1, 1931) quoted in Robins, Anthony W. "McGraw-Hill Building Designation Report" New York Landmarks Preservation Commission (September 11, 1979)

- Griswold, J. B. "Nine Years Ago, Raymond M Hood Was Behind in his Rent ... Today - he holds the spotlight as a master shoman of stone and steel" American Magazine (October 1931) p.145, quoted in Robins, Anthony W. "McGraw-Hill Building Designation Report" New York Landmarks Preservation Commission (September 11, 1979)

- "Architecture of the Night" General Electric Company (1930)

- Heynick, Frank. "Peter Keating designed Rockefeller Center?" on The Atlasphere website (September 7, 2009)

- Gray, Christopher (November 4, 1990). "Streetscapes: The Bleecker Street Cinema; The 'Lost' Frescoes of an Artist-Soldier". The New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

Bibliography

- Duval, Jonathan and Dietrich Neumann, Raymond Hood and the American Skyscraper. Providence, RI: Bell Gallery, Brown University, 2020.

- Frampton, Kenneth. "Storia dell'Architettura Moderna" 4a edizione, Zanichelli

- Gargiani, Roberto. Rem Koolhaas/Oma. Grandi Opere-Gli Architetti, editori Laterza

- Hood, Raymond M. (1931) Contemporary American Architects: Raymond M. Hood. New York: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill. ISBN 1135799431

- Features a large collection of photographs of Hood's works.

- Kilham, Walter H. (1973). Raymond Hood, Architect - Form Through Function in the American Skyscraper. Architectural Book Publishing Co Inc, New York.

- Kvaran, Einar Einarsson. Architectural Sculpture of America. unpublished manuscript

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raymond Hood. |

- Works by or about Raymond Hood at Internet Archive

- Raymond M. Hood architectural drawings and papers, circa 1890-1944.Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- The Raymond Hood Photograph Collection at the New-York Historical Society

_(cropped).jpg.webp)