Realdo Colombo

Matteo Realdo Colombo (c. 1515 – 1559) was an Italian professor of anatomy and a surgeon at the University of Padua between 1544 and 1559.

Early life and education

Matteo Realdo Colombo or Realdus Columbus, was born in Cremona, Lombardy, the son of an apothecary named Antonio Colombo. Although little is known about his early life, it is known he took his undergraduate education in Milan, where he studied philosophy,[1] and he appears to have pursued his father's profession for a short while afterwards. He left the apothecary's life and apprenticed to the surgeon Giovanni Antonio Lonigo, under whom he studied for 7 years. In 1538 he enrolled in the University of Padua where he was noted to be an exceptional student of anatomy. While still a student, he was awarded a Chair of Sophistics at the university. In 1542 he returned briefly to Venice to assist his mentor, Lonigo.

Academic career

Realdo Colombo studied philosophy in Milan, and then he trained to be a surgeon for several years under a Venetian named Giovanni Antonio Plato, also known as Lonigo or Leonicus. By 1538, during the years of Andreas Vesalius, Columbo had arrived at Padua where he studied medicine, anatomy, and he lectured to arts students on sophistics, or logic. Columbo became a close friend of Vesalius and possibly assisted him at a dissection. Vesalius was away in Basle when Columbo was temporarily appointed to teach in his place, and eventually, Colombo received this position more permanently.

In 1544, Colombo went to the University of Pisa and performed many dissections; he was referred to “As Master of Anatomy and Surgery.” Then in 1548, Columbo went to Rome where he taught anatomy at the papal university for about ten years until his death in 1559. While Colombo was in Rome, he took on a project with Michelangelo and became his personal physician and friend. He intended to collaborate with Michelangelo on an illustrated anatomy text to rival De Fabrica but this never came to pass, likely due to Michelangelo's advanced age. Although not much is known about Colombo's biography, his relationship with the more familiar Michelangelo has helped historians better understand his views.[2] He also performed the autopsy on the body of St. Ignatius of Loyola.[3]

Colombo and Vesalius

The relationship between Colombo and Vesalius is not entirely clear. Colombo was appointed to one of the posts in surgery at the University of Padua in 1541 to replace Vesalius while he traveled to Basle in order to supervise the printing of De humani corporis fabrica. [2] It is often thought that Colombo was a student of Vesalius, but this may not have been the case. Regardless, they had become bitter rivals by 1555. While teaching Vesalius' classes in 1543, Colombo pointed out several errors Vesalius made, most notably attributing properties of cows' eyes to the eyes of humans as well as claiming to have discovered a vein in the human body, the existence of which Vesalius had previously denied.[2] Although Vesalius has been much maligned for correcting Galen, Colombo was the one to criticize him for his own mistakes. When Vesalius returned, he was outraged. He publicly ridiculed Colombo, calling him an "Ignoramus" and stating that "what meager knowledge [Colombo] has of anatomy he learned from me" on a number of occasions. Despite Vesalius's claims, it is likely that Colombo was a proper colleague of Vesalius rather than a student. For one thing, Vesalius attributes many of his discoveries in De Fabrica to Colombo who is referred to as a, "very good friend." Vesalius and Colombo were also from very different academic backgrounds. Vesalius was a Galenic expert, trained in Leuven, whereas Colombo began his study of anatomy as a surgeon. Finally, Colombo refers frequently to Lonigo as his teacher of surgery and anatomy, never mentioning Vesalius. While both Colombo and Vesalius were in favor of returning to the anatomical practice of vivisection, as the Alexandrians did, Colombo was the only one to actually do so. This is one of the main reasons as to why Colombo criticized Vesalius. Vesalius criticized Galen while he himself continued to show the anatomy of animals, instead of humans, in his book.[2]

Colombo and Falloppio

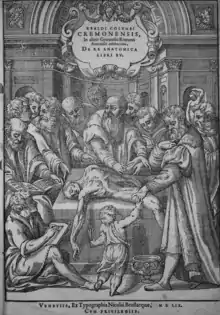

Colombo's only published text, De Re Anatomica, was released shortly after his death in 1559. His sons, Lazarus and Phoebus, were responsible for overseeing the final stages of the publishing process of his book after Colombo’s death interrupted it. [4] Many of the contributions made in De Re Anatomica overlapped the discoveries of another anatomist, Gabriele Falloppio, most notably in that both Colombo and Falloppio claimed to have discovered the clitoris. Although both Colombo and Falloppio gave claim to what was actually the re-discovery of the clitoris, it is Colombo who is credited as having been the anatomist who correctly identified the clitoris as a predominantly sexual organ. Falloppio published his own book, Observationes Anatomicae, in 1561, but there is evidence that Falloppio had written notes on his discovery of the clitoris eleven years earlier in 1550.[5] In 1574, Leone Giovanni Battista Carcano (1536–1606), a student of Falloppio, formally charged Colombo of plagiarism, although since Colombo had been dead for over a decade nothing came of these charges.

Colombo’s criticisms of Galen

Realdo Colombo did not accept the work of previous anatomists without proof, and in some cases sought to criticize or discredit them. He especially criticized Galen’s work, and was angered by those who swore on Galen’s ideas, saying “that they dare to affirm that Galen is to be taken as Gospel, and that nothing in his writing is not true!” For example, he argued that Galen’s use of animals in dissection was not solid evidence that his anatomy was sound. He also criticized Vesalius for his hypocrisy in correcting Galen’s work while still avoiding human dissection. Colombo instead respected the work of Alexandrian physicians, as he viewed their use of human dissection as more accurate than animal dissection or vivisection. His use of vivisection to examine the contractions of the heart and arteries contradicted Galen’s findings, and supported the theories of the Alexandrian physician Erasistratus.

Prior to Colombo’s work, anatomists such as Galen and Vesalius examined blood vessels separately from the organs of the body. Colombo instead considered these vessels together with the organs they support, and from this was able to conceptualize the flow of blood to and from each organ, supporting his discovery of pulmonary transition of the blood. Colombo also viewed the lungs separately from the heart, and assigned it as having a special role in respiration. This approach to examination gave him a more firm understanding of the functions of the organs as well, and strengthened his criticisms of Galen.[6]

Methodology

Colombo put an emphasis on vivisection, the practice of experimentation or scientific research on live animals, in order to learn about the different bodily functions of the human body. According to Colombo’s book, “De Re Anatomica Libri XV,” he put energy into dissecting, in particular the cadavers of men. Colombo anatomized the live, active body whereas his contemporaries had anatomized the dead body. Colombo’s concentration on vivisection revived the practice of ancient Alexandrian anatomists, using live animals instead of dead, which led him to adopting this new way of conceptualizing the body. The vivisection method enabled Colombo to study the operation of the voice, the motion of the lungs, the heart and the motion of the arteries, the dilation and contraction of the brain, variations of the pulse and other functions.[2]

With the centrality of vivisection, the three ‘rivers’ was also emphasized in Colombo’s book, specifically Book XI. “There are three fountain-heads, the liver, heart, and brain, from which are distributed throughout the body the three rivers of the natural blood, the vital blood and the animal spirits respectively. The view of the three rivers does not come from any known ancient source.”[2] Although there were many important organs like the liver in the abdomen area and the heart, for Columbo, the supreme organ was the brain. Colombo described the organs in the form of hierarchy and because the brain was said to be the most noble of organ, it was ‘King of the principal members’ of the body. The supremacy of the brain was directly related to his view of the three rivers. “What is generated in the brain and distributed through the nerves, is what differentiates the live body from the dead one.”[2] Among other reasons, the most important one for the brain being King of all organs, is the fact that the brain is the source of sense and motion.[2]

Contributions to anatomy

Colombo made several important advances in anatomy, including the discovery of the pulmonary circuit which paved the way for William Harvey's discovery of circulation years later. In the Galenic tradition, blood passed between the ventricles of the heart through micropores in the heart's septum and venous blood became arterial blood in the left ventricle of the heart where air was supplied by the pulmonary vein. During vivisections of dogs and other animals, Colombo repeatedly found only blood, and no air, in the pulmonary vein. In his model, venous blood travelled from the heart to the lungs where it was mixed with air and then returned to the heart.[7] The permeability of the septum was questioned by Michael Servetus in Christianismi Restitutio in 1553 and by Ibn al-Nafis in the 13th century and both proposed that the blood was pushed from the right ventricle to the left via the lungs, however, both of these accounts were largely forgotten. Colombo was the first to propose the pulmonary circuit in an intellectual climate that could expand on his theory. In addition to the pulmonary circuit, Colombo also discovered that the main action of the heart was contraction, rather than dilation as had previously been thought. Both of these discoveries were later confirmed by William Harvey.

In addition, Colombo is credited with coining the term "placenta"[8] and in his work describes the placenta as a place where pure and perfect blood is stored for the baby before birth. He believes Galen misinterpreted the placenta when it comes to humans and challenges Galen’s views on the placenta because Galen only performed dissections on animals. Colombo argues that performing vivisections helps one to understand how the system works as a whole. At the time his work in this anatomical area was revolutionary and provided the basis for the understanding of the placenta and other anatomical structures we have today. These detailed descriptions and critiques are in his book De Re Anatomica Libri XV.[9]

Much cited is Columbo's naming and description of the clitoris as "Amor Veneris, vel Dulcedo Appelletur." He stated, "It should be called the love or sweetness of Venus."[10] (See historical and modern perceptions of the clitoris.) While Colombo was not the first to discover the clitoris, he is one of the first to propose its role in female sexual pleasure. This finding caused quite a stir amongst the general public as it was already thought that females had anatomy corresponding to their male counterparts; the addition of a bodily structure could cause women to be viewed as hermaphrodites.[11] Politically, this had implications as it was suggested that women could be anatomically equal to men.

Written works

The structure of Colombo's book, On anatomizing, is indicative of the way in which Colombo went about dissecting subjects for his research. Not only was the order and structure of this work very thought out, but also it differed from the structure of other anatomists at the time.

Colombo's anatomical text consisted of 15 different books, each of which covered information concerning a different part of the body. Book 1 described the bones, while Book 2 and Book three, respectively, outlined the cartilages and ligaments that could be found within the human body. Book 4 explains the skeleton as a whole, bringing together the individually discussed anatomical elements described in the preceding three books. The muscles of the human body are described in Book 5, and the liver and veins share the content of Book 6. Book 7 explains the heart and arteries and is followed by a Book 8's discussion of the brain and nerves. Glands in general are described in Book 9, and Book 10 is dedicated to the explanation of the eyes. The viscera are covered in Book 11. Book 12 outlines the formation of the fetus while book 13 details the covering of the human body, or skin. Vivisections, a practice used regularly by Colombo are described in Book 14. Book 15 closes out the anatomical text by listing things Colombo himself saw that fell under the category of "things rarely seen in anatomy."

This method of organizing his anatomical work was, at this time, a break from previous anatomizing tradition. Colombo dealt with each major organ in conjunction with their vessels, whereas previous anatomists, including Vesalius, separated organs from their vessels. In addition to this break from tradition, Colombo did not include the lungs in his discussion of the heart and their vessels, the arteries. It was this severing of the conceptual link between the lungs and the heart that had existed since the time of Galen that made Colombo’s discovery of the pulmonary transit of blood possible.[2]

Realdo Colombo in fiction

In modern historical fiction, Realdo Columbo is the topic of Argentine author Federico Andahazi, who published El anatomista in Spanish in 1997, and the English version, The Anatomist, in 1998. The novel is aimed at discussing the implications of the discovery of the clitoris, the dawn of the age of observation as opposed to a priori thinking, and the parallels between Realdo Columbo and Christopher Columbus, both discoverers eminent in their respective domains.[12] Andahazi’s work has had some detractors, Elizabeth Harvey for example thinks that, “this work nevertheless demonstrates its profound complicity with the antifeminist [sic] rhetoric and medical ideology that support the sexual subjugation of women."[12] Corbett suggested that the work is considered more fiction than history, and that critics are wasting time on something that does not purport to be very accurate (Corbett 2004).

In The Anatomist, Columbo is described as being madly in love with a prostitute who works at a brothel in Venice, and he spends his time and money attempting to persuade her to run away with him. The work has a strange erotic context, where much of the imagery and narration is explicitly detailed.

Andahazi also seems intent on comparing Realdo Columbo with Christopher Columbus and comparing their discoveries. While both made discoveries, it is doubtful that the clitoris was truly a mystery to women, and obviously incorrect that the natives of the West Indies and continental present day United States were unaware of the land they resided on. Rather, Andahazi tries to explain the significance of the discoveries in terms of European enlightenment thinking. While the discovery of the New World was undoubtedly revolutionary in Europe, “The impact of the spreading awareness of the clitoris is not as well documented. Andahazi, however, leans on the Christopher Columbus result to suggest his counter-historical claim that the other discover [sic], too, has changed the world of every day living. It’s not so obvious that this is so” (Corbett 2004).

- Andahazi, Federico (1998). The Anatomist. ISBN 978-0-385-49400-7.

References

- Cunningham, Andrew (1997). The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Scholar Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-85928-338-7.

- Cunningham, Andrew (1997).

- Pizzi, M., M. Fassan, M. Cimino, V. Zanardo, and S. Chiarelli. "Placenta." Journal of the International Federation of Placenta Associations. ELSEVIER, 13 Mar. 2012. Web. <www.elsevier.com%2Flocate%2Fplacenta>.

- Cunningham, Andrew (1997). The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Scholar Press. p. 148. ISBN 1-85928-338-1

- Hillman, David, and Carla Mazzio. The Body in Parts: Fantasies of Corporeality in Early Modern Europe. New York: Routledge, 1997. Print p 177

- Cunningham, Andrew (1997). The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Scholar Press. p. 143. ISBN 1-85928-338-1.

- Colombo, Realdo (1559). De Re Anatomica. Libri XV [On Anatomy. In 15 books.] (in Latin). Venice, (Italy): Nicolai Bevilacqua. p. 177. From p. 177: "Inter hos ventriculos septum adest, per quod fere omnes existimant sanguini a dextro ventriculo ad sinistrum aditum patefieri. id ut fiat facilius, in transitu ob vitalium spirituum generationem tenuem reddi. sed longa errant via, nam sanguis per arteriosam venam ad pulmonem fertur, ibique; attenuatur; deinde cum aere una per arteriam venalem ad sinistrum cordis ventriculum defertur; … " (Between these ventricles, a septum [i.e., wall] is present, through which (everyone supposes) an entrance is opened, for the blood, from the right ventricle to the left [one], so that it becomes easier, upon [the blood's] passing [through this opening], for the subtle generation of the vital spirits to be repeated. But they [i.e., the vital spirits] wander along a long path, because the blood is carried by the pulmonary artery to the lung, and therein it is made thin [i.e., less viscous]; from there, it is conveyed, with an air, by the pulmonary vein to the left ventricle of the heart; … )

- Colombo, Realdo (1559). De Re Anatomica. Libri XV [On Anatomy. In 15 books.] (in Latin). Venice, (Italy): Nicolai Bevilacqua. p. 248. From p. 248: " … ut fulcirentur, natura affusionem quandam genuit, quæ orbicularis fit placentæ in modum." ( … in order that they [viz, the blood vessels that branch, within the placenta, from the umbilical cord ] be supported, Nature creates a certain casting [i.e., matrix], which [is] spherical [and] is made of a cake-like [tissue].) In the adjoining margin: "Affusio orbicularis instar placẽtæ." (The spherical matrix [has] the appearance of a flat cake.) Joseph Hyrtl explained Colombo's use of the word affusio: Hyrtl, Joseph (1879). Das Arabische und Hebräische in der Anatomie [Arabic and Hebrew in Anatomy] (in German). Vienna, Austria: Wilhelm Braumüller. pp. 285–286. On p. 230 of Columbo's book, he called the pancreas the affusio because it seemed to have been cast (Latin: affusus or adfusus) in order to support the stomach and/or the blood vessels within the abdomen. Similarly, the placenta supported the blood vessels that branched from the umbilical cord: from p. 285 of Hyrtl: "Um die Ramificationen der Nabelgefässe zu stützen und mit einander zusammenzuhalten, natura affusionem quandam genuit, quae facta est, ut vasa unita detineret." (In order to support the branchings of the umbilical [blood] vessels and to hold them together, Nature creates a certain casting [i.e., matrix], which is made in order that the vessels be kept united.) Thus, although Colombo called the placenta the "affusio orbicularis", it was his characterization of the placenta – cake-like (placenta) – that prevailed.

- Pizzi, M., M. Fassan, M. Cimino, V. Zanardo, and S. Chiarelli

- Elizabeth D. Harvey (Winter 2002). "Anatomies of Rapture: Clitoral Politics/Medical Blazons". Signs. 27 (2): 315–346. doi:10.1086/495689. JSTOR 3175784.

- Hillman, David, and Carla Mazzio. The Body in Parts: Fantasies of Corporeality in Early Modern Europe. New York: Routledge, 1997. Print.

- Elizabeth D. Harvey (Winter 2002)

External links

- http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04125a.htm

- http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?tocId=9024815

- http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a3_212b.html

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Realdo Colombo in .jpg and .tiff format.