Lombardy

Lombardy (/ˈlɒmbərdi, ˈlʌm-/ LOM-bər-dee, LUM-;[6][7] Italian: Lombardia [lombarˈdiːa]; Lombard: Lombardia, Western Lombard: [lũbɐ̞rˈdiːɑ], Eastern Lombard: [lombɐ̞rˈdiːɑ, -ˈdeːɑ]) is one of the twenty administrative regions of Italy, in the northwest of the country, with an area of 23,844 square kilometres (9,206 sq mi). About 10 million people live in Lombardy, forming more than one-sixth of Italy's population, and more than a fifth of Italy's GDP is produced in the region, making it the most populous, richest and most productive region in the country. It is also one of the top regions in Europe for the same criteria.[8][9] Milan's metropolitan area is the largest in Italy and the third most populated functional urban area in the EU.[10] Lombardy is also the Italian region with most UNESCO World Heritage Sites—Italy (tied with China) having the highest number of World Heritage Sites in the world.[11] The region is also famous for its historical figures such as Virgil, Pliny the Elder, Ambrose, Caravaggio, Claudio Monteverdi, Antonio Stradivari, Cesare Beccaria, Alessandro Volta, Alessandro Manzoni, and popes John XXIII and Paul VI.

Lombardy

| |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: Lombardia, Lombardia[1] | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°35′08″N 9°55′49″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Capital | Milan |

| Government | |

| • Type | President–council government |

| • Body | Regional Cabinet |

| • President | Attilio Fontana |

| • Legislature | Regional Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23,844 km2 (9,206 sq mi) |

| Population (31 December 2019)[2] | |

| • Total | 10,103,969 |

| • Density | 420/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Lombard Italian: Lombardo (man) Italian: Lombarda (woman) Lombard: Lombard (man) Lombard: Lombarda (woman) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IT-25 |

| GDP (nominal) | €388 billion (2018)[3] |

| GDP per capita | €38,600 (2018)[3] $51,666 (2016) (PPP)[4] |

| HDI (2018) | 0.902[5] very high · 4th of 21 |

| NUTS Region | ITC |

| Website | www.regione.lombardia.it |

Etymology

The word Lombardy comes from Lombard, which in turn is derived from Late Latin Longobardus, Langobardus ("a Lombard"), derived from the Proto-Germanic elements *langaz + *bardaz; equivalent to long beard. Some scholars suggest the second element instead derives from Proto-Germanic *bardǭ, *barduz ("axe"), related to German Barte ("axe") or that the whole word comes from the Proto-Albanian *Lum bardhi "white river" (Compare modern Albanian lum i bardhë).[12]

During the early Middle Ages, "Lombardy" referred to the Kingdom of the Lombards (Latin: Regnum Langobardorum), a kingdom ruled by the Germanic Lombards who had controlled most of Italy since their invasion of Byzantine Italy in 568. As such "Lombardy" and "Italy" were almost interchangeable; by the mid-8th century the Lombards ruled everywhere except the Papal possessions around Rome (roughly modern Lazio and northern Umbria), Venice and some Byzantine possessions in the south (southern Apulia and Calabria; some coastal settlements including Amalfi, Gaeta, Naples and Sorrento; Sicily and Sardinia). The Kingdom was divided between Longobardia Major in the north and Langobardia Minor in the south by the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna (roughly Romagna and northern Marche, and initially also Emilia and Liguria) until the 8th century and later the Papacy (which was initially part of the Exarchate). During the late Middle Ages, after the fall of the northern part of the Kingdom to Charlemagne, the term shifted to mean Northern Italy. (See: Kingdom of Italy (Holy Roman Empire)). The term was also used until around 965 in the form Λογγοβαρδία (Longobardia) as the name for the territory roughly covering modern Apulia which the Byzantines had recovered from the Lombard rump Duchy of Benevento.

Geography

With a surface of 23,861 km2 (9,213 sq mi), Lombardy is the fourth-largest region of Italy. It is bordered by Switzerland (north: Canton Ticino and Canton Graubünden) and by the Italian regions of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and Veneto (east), Emilia-Romagna (south), and Piedmont (west). Three distinct natural zones can be easily distinguished in Lombardy: mountains, hills, and plains—the last being divided into Alta (high plains) and Bassa (low plains).

Soils

The orography of Lombardy is characterised by the presence of three distinct belts: a northern mountainous belt constituted by the Alpine relief, a central piedmont area of mostly pebbly soils of alluvial origin, and the Lombard section of the Padan Plain in the southernmost part of the region.

The most important mountainous area is the Alpine zone including the Lepontine and Rhaetian Alps (Piz Bernina, 4,020 m), the Bergamo Alps, the Ortler Alps and the Adamello massif. It is followed by the Alpine foothills zone Prealpi, the main peaks of which are the Grigna Group (2,410 m), Resegone (1,875 m), and Presolana (2,521 m).

The plains of Lombardy, formed by alluvial deposits, can be divided into the Alta—an upper, permeable ground zone in the north—and the Bassa—a lower zone dotted by the so-called line of fontanili, spring waters rising from impermeable ground. Inconsistent with the three distinctions above is the small subregion of Oltrepò Pavese, formed by the Apennine foothills beyond the Po River.

Hydrography

The mighty Po river marks the southern border of the region for a length of about 210 km (130 mi). In its progress, it receives the waters of the Ticino River, which rises in the Bedretto valley (Switzerland) and joins the Po near Pavia. The other streams which contribute to the great river are the Olona, the Lambro, the Adda, the Oglio and the Mincio.

The numerous lakes of Lombardy, all of glacial origin, lie in the northern highlands. From west to east these are Lake Maggiore, Lake Lugano (both shared with Switzerland), Lake Como, Lake Iseo, Lake Idro, and Lake Garda (the largest lake in Italy). South of the Alps lie the hills characterised by a succession of low heights of morainic origin formed during the last Ice Age and small barely fertile plateaux with typical heaths and conifer woods. A minor mountainous area, the Oltrepò Pavese, lies south of the Po, in the Apennines range.

Flora and fauna

In the plains, intensively cultivated for centuries, little of the original environment remains. The most common trees are elm, alder, sycamore, poplar, willow and hornbeam. In the area of the foothills lakes, however, grow olive trees, cypresses and larches, as well as varieties of subtropical flora such as magnolias, azaleas, acacias. Numerous species of endemic flora in the Prealpine area include some kinds of saxifrage, the Lombard garlic, groundsels bellflowers and the cottony bellflowers.

The highlands are characterised by the typical vegetation of the whole range of the Italian Alps. At lower levels (up to approximately 1,100 m), oak woods or broadleafed trees grow; on the mountain slopes (up to 2,000–2,200 m), beech trees grow at the lowest limits, with conifer woods higher up. Shrubs such as rhododendron, dwarf pine and juniper are native to the summital zone (beyond 2,200 m).

Lombardy counts many protected areas: the most important are the Stelvio National Park (the largest Italian natural park), with typically alpine wildlife: red deer, roe deer, ibex, chamois, foxes, ermine and also golden eagles; and the Ticino Valley Natural Park, instituted in 1974 on the Lombard side of the Ticino River to protect and conserve one of the last major examples of fluvial forest in northern Italy.

Other Parks situated in the region are the Campo dei Fiori and the Cinque Vette Park, both of them are located in the Province of Varese.

Climate

Lombardy has a wide array of climates, due to local variances in elevation, proximity to inland water basins, and large metropolitan areas.

The climate of the region is mainly humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa) especially in the plains, though with significant variations to the Köppen model especially regarding the winter season, which in Lombardy is normally long, damp, and rather cold. In addition, there is a high seasonal temperature variation (in Milan, the average temperature is 2.5 °C (36.5 °F) in January and 24 °C (75 °F) in July). The plains are often subject to the presence of fog during the coldest months.

In the Alpine foothills, characterised by an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb), numerous lakes exercise a mitigating influence, allowing the cultivation of typically Mediterranean crops (olives, citrus fruit).

In the hills and mountains, the climate is humid continental (Köppen Dfb). In the valleys it is relatively mild, while it can be severely cold above 1,500 m, with copious snowfalls.

Precipitation is more intense in the Prealpine zone, up to 1,500 to 2,000 mm (59.1 to 78.7 in) annually, but is abundant also in the plains and alpine zones, with an average of 600 to 850 mm (23.6 to 33.5 in) annually. The total annual rainfall is on average 827 mm.[13]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

.jpg.webp)

It is thought from the archaeological findings of ceramics, arrows, axes, and carved stones that the area of current Lombardy has been settled at least since the 2nd millennium BC. Well-preserved rock drawings left by ancient Camuni in the Valcamonica depicting animals, people, and symbols were made over a time period of eight thousand years preceding the Iron Age,[15] based on about 300,000 records.[16]

The many artifacts (pottery, personal items and weapons) found in necropolis near the Lake Maggiore, and Lake Ticino demonstrate the presence of the Golasecca Bronze Age culture that prospered in Western Lombardy between the 9th and the 4th century BC.

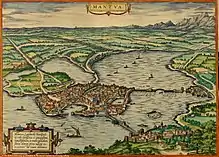

In the following centuries it was inhabited by different peoples, among whom were the Etruscans, who founded the city of Mantua and spread the use of writing. It was seat of the Celtic Canegrate culture (starting from the 13th Century BC) and later of the Celto-Ligurian Golasecca culture. Later, starting from the 5th century BC, the area was invaded by more Celtic Gallic tribes coming from north of the Alps.. These people settled in several cities including Milan, and extended their rule to the Adriatic Sea.

Their development was halted by the Roman expansion in the Po Valley from the 3rd century BC onwards. After centuries of struggle, in 194 BC the entire area of what is now Lombardy became a Roman province with the name of Gallia Cisalpina ("Gaul on the inner side (with respect to Rome) of the Alps").

The Roman culture and language overwhelmed the former civilisation in the following years, and Lombardy became one of the most developed and richest areas of Italy with the construction of a wide array of roads and the development of agriculture and trade. Important figures were born here, like Pliny the Elder (in Como) and Virgil (in Mantua). In late antiquity the strategic role of Lombardy was emphasised by the temporary moving of the capital of the Western Empire to Mediolanum (Milan). Here, in 313 AD, Roman Emperor Constantine issued the famous Edict of Milan that gave freedom of confession to all religions within the Roman Empire.

Kingdom of the Lombards

During and after the fall of the Western Empire, Lombardy suffered heavily from destruction brought about by a series of invasions by tribal peoples. The last and most effective was that of the Germanic Lombards, or Longobardi, whose whole nation migrated here from the Carpathian basin in fear of the conquering Pannonian Avars in 568 and whose long-lasting reign (with its capital in Pavia) gave the current name to the region. There was a close relationship between the Frankish, Bavarian and Lombard nobility for many centuries.

After the initial struggles, relationships between the Lombard people and the Latin-speaking people improved. In the end, the Lombard language and culture assimilated with the Latin culture, leaving evidence in many names, the legal code and laws, and other things. The genes of the Lombards became quickly diluted into the Italian population owing to their relatively small number and their geographic dispersal to rule and administer their kingdom.[17] The end of Lombard rule came in 774, when the Frankish king Charlemagne conquered Pavia, deposed Desiderius, the last Lombard king, and annexed the Kingdom of Italy (mostly northern and central present-day Italy) to his newly established Holy Roman Empire. The former Lombard dukes and nobles were replaced by other German vassals, prince-bishops or marquises.

Communes and the Empire

In the 10th century, Lombardy, although formally under the rule of the Holy Roman Empire like much of central and northern Italy, was in fact divided in a multiplicity of small, autonomous city-states, the medieval communes. The 11th century marked a significant boom in the region's economy, due to improved trading and, most importantly, agricultural conditions, with arms manufacture a significant factor. In a similar way to other areas of Italy, this led to a growing self-acknowledgement of the cities, whose increasing richness made them able to defy the traditional feudal supreme power, represented by the German emperors and their local legates. This process reached its apex in the 12th and 13th centuries, when different Lombard Leagues formed by allied cities of Lombardy, usually led by Milan, managed to defeat the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick I, at Legnano, and his grandson Frederick II, at Parma. Subsequently, among the various local city-states, a process of consolidation took place, and by the end of the 14th century, two signorias emerged as rival hegemons in Lombardy: Milan and Mantua.

Renaissance duchies of Milan and Mantua

In the 15th century, the Duchy of Milan was a major political, economical and military force at the European level. Milan and Mantua became two centres of the Renaissance whose culture, with men such as Leonardo da Vinci and Mantegna, and works of art (e.g. Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper) were highly regarded. The enterprising class of the communes extended its trade and banking activities well into northern Europe: "Lombard" designated the merchant or banker coming from northern Italy (e.g. Lombard Street in London). The name "Lombardy" came to designate the whole of Northern Italy until the 15th century and sometimes later. From the 14th century onwards, the instability created by the unceasing internal and external struggles ended in the creation of noble seigniories, the most significant of which were those of the Viscontis (later Sforzas) in Milan and of the Gonzagas in Mantua. This richness, however, attracted the now more organised armies of national powers such as France and Austria, which waged a lengthy battle for Lombardy in the late 15th to early 16th centuries.

Late-Middle Ages, Renaissance and Enlightenment

After the decisive Battle of Pavia, the Duchy of Milan became a possession of the Habsburgs of Spain: the new rulers did little to improve the economy of Lombardy, instead imposing a growing series of taxes needed to support their unending series of European wars. The eastern part of modern Lombardy, with cities like Bergamo and Brescia, was under the Republic of Venice, which had begun to extend its influence in the area from the 14th century onwards (see also Italian Wars). Between the middle of the 15th century and the battle of Marignano in 1515, the northern part of east Lombardy from Airolo to Chiasso (modern Ticino), and the Valtellina valley came under possession of the old Swiss Confederacy.

Pestilences (like that of 1628/1630[18] described by Alessandro Manzoni in his I Promessi Sposi) and the generally declining conditions of Italy's economy in the 17th and 18th centuries halted the further development of Lombardy. In 1706 the Austrians came to power and introduced some economic and social measures which granted a certain recovery.

Austrian rule was interrupted in the late 18th century by the French armies; under Napoleon, Lombardy became the centre of the Cisalpine Republic and of the Kingdom of Italy, both being puppet states of France's First Empire, having Milan as capital and Napoleon as head of state. During this period Lombardy took back Valtellina from Switzerland.

Modern era

The restoration of Austrian rule in 1815, as the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, was characterised by the struggle with the new ideals introduced by the Napoleonic era.

The popular republic established by the 1848 revolution was short-lived, its suppression leading to renewed Austrian rule. This came to a decisive end when Lombardy was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy 1859 as a result of the Second Italian War of Independence from the Austrian Empire. When annexed to the Kingdom of Italy in 1859 Lombardy achieved its present-day territorial shape by adding the Oltrepò Pavese (formerly the southern part of Novara's Province) to the province of Pavia.

COVID-19 pandemic

The Lombardy region was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, in which Italy was one of the worst affected countries in Europe; the outbreak in Italy significantly accelerated the global spread of COVID-19. Several towns were quarantined from 22 February after community transmission was documented in Lombardy and Veneto the previous day. The entire Lombardy region was placed on lockdown on 8 March,[19] followed by all of Italy the following day,[20] making Italy the first country to implement a nationwide lockdown in response to the epidemic, which was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March. The lockdown was ultimately extended twice, and the Lombardy region toughened restrictions on 22 March, banning outdoor exercise and the use of vending machines,[21] but from the beginning of May, following a decrease in the number of active cases, restrictions gradually began to be relaxed.[22]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 3,160,000 | — |

| 1871 | 3,529,000 | +11.7% |

| 1881 | 3,730,000 | +5.7% |

| 1901 | 4,314,000 | +15.7% |

| 1911 | 4,889,000 | +13.3% |

| 1921 | 5,186,000 | +6.1% |

| 1931 | 5,596,000 | +7.9% |

| 1936 | 5,836,000 | +4.3% |

| 1951 | 6,566,000 | +12.5% |

| 1961 | 7,406,000 | +12.8% |

| 1971 | 8,543,000 | +15.4% |

| 1981 | 8,892,000 | +4.1% |

| 1991 | 8,856,000 | −0.4% |

| 2001 | 9,033,000 | +2.0% |

| 2011 | 9,704,151 | +7.4% |

| 2019 (est.) | 10,067,500 | +3.7% |

| Source: ISTAT 2017 | ||

| The largest resident foreign-born groups on 31 December 2017[23] | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | Population |

| 172,045 | |

| 93,763 | |

| 92,565 | |

| 80,939 | |

| 66,618 | |

| 58,412 | |

| 53,360 | |

| 46,274 | |

| 42,992 | |

| 37,970 | |

| 37,290 | |

| 33,510 | |

| 32,245 | |

| 21,615 | |

| 20,661 | |

| 16,907 | |

| 14,147 | |

| 13,641 | |

| 11,747 | |

| 10,876 | |

| 10,645 | |

| 10,366 | |

| 9,993 | |

| 9,030 | |

One-sixth of the Italian population or about 10 million people live in Lombardy (16.2% of the national population; 2% of the European Union population), making it the second most densely populated region in Italy after Campania.

The population is highly concentrated in the Milan metropolitan area (2,000 inh./km2) and the Alpine foothills that compose the southern section of the provinces of Varese, Como, Lecco, Monza and Brianza and Bergamo, (1,200 inh./km2). A lower average population density (250 inh./km2) is found in the Po valley and the lower Brescia valleys; much lower densities (less than 60 inh./km2) characterise the northern mountain areas and the southern Oltrepò Pavese subregion.[24]

The growth of the regional population was particularly sustained during the 1950s–60s, thanks to a prolonged economic boom, high birth rates, and strong migration inflows (especially from Southern Italy). Since the 1980s, Lombardy has become the destination of a large number of international migrants, insomuch that today, more than a quarter of all foreign-born residents in Italy live in this region. As of 2016, the Italian national institute of statistics (ISTAT) estimated that 1,139,430 foreign-born immigrants live in Lombardy, equal to 11.4% of the total population. The primary religion is Catholicism; significant religious minorities include Christian Waldenses, Protestants and Orthodox, as well as Jews, Sikh and Muslims.

Economy

As of 2013, the gross domestic product (GDP) of Lombardy, equal to over €350 billion, accounts for about 21% of the total GDP of Italy. By inhabitant, this figure results in a value of €33,066, which is more than 25% higher than the national average of €25,729.[24]

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP[25] (Euro) | 247.051,8 | 259.431 | 270.653,3 | 279.450,4 | 289.471,2 | 297.600,4 | 307.717,7 | 320.843,8 | 323.973,3 | 310.952 | 346.797 | 354.342 | 348.665 | 349.008 | 350.025 | 357.200 | 375.270 | 385.133 | 390.461 |

| GDP per capita[25] (Euro) | 27.488,1 | 28.765,6 | 29.836,9 | 30.448,8 | 31.059,5 | 31.545,2 | 32.356,3 | 33.442,5 | 33.424,8 | 31.743,1 | 35.712,55 | 36.220,23 | 35.367,31 | 35.126,67 | 35.044,17 | 35.700,0 | 37.474,09 | 38.406,9 | 38.857,6 |

Lombardy's development has been marked by the growth of the services sector since the 1980s, and in particular by the growth of innovative activities in the sector of services to enterprises and in credit and financial services. At the same time, the strong industrial vocation of the region has not suffered. Lombardy remains, in fact, the main industrial area of the country. The presence, and development, of a very high number of enterprises belonging to the services sector represents a favourable situation for the improvement of the efficiency of the productive process, as well as for the growth of the regional economy.

Lombardy has cultural and economical relationships with many foreign countries including Azerbaijan,[27] Austria,[28][29][30] France,[31] Hungary,[32][33][34][35][36] Switzerland (especially the cantons of Ticino and Graubünden),[37][38][39][40][41] Canada (the Province of Quebec),[42] Germany (the States of Bavaria, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt),[43][44][45] Kuwait,[46] the Netherlands (Province of Zuid-Holland),[47] and Russia.[48] Lombardy is a member of the Four Motors of Europe, an intereuropean economical organization which includes Baden-Wurtenberg in Germany, Catalonia in Spain, and Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes in France.[49] The Lombardy region is also part of the EUSALP, which promotes innovation, green sustainability, and economy in the Alpine regions of Austria, France, Liechtenstein, Northern Italy, Southern Germany, Switzerland, and Slovenia,[50][51][52] and ARGE ALP, which gathers states located in the alpine regions of Austria, Northern Italy, Southern Germany, and Switzerland to discuss similar themes as in EUSALP.[53] Economical and cultural relationship are also strong with neighboring Italian regions Friuli-Venezia Giulia, South Tyrol, Trentino, and Veneto.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64] The European Union has developed the CENTRAL EUROPE program 2014–2020 to foster cooperation in several areas between the Lombardy Region along with other Northern Italian Regions and several states of Central Europe.[65][66]

The region can broadly be divided into three areas in regards to productive activity: Milan, where the services sector makes up for 65.3% of the employment; the provinces of Varese, Como, Lecco, Monza and Brianza, Bergamo and Brescia, where it is highly industrialised, although in the two latter provinces, there is also a rich agricultural sector in the plains; the provinces of Sondrio, Pavia, Cremona, Mantova and Lodi, where there is a consistent agricultural activity, and at the same time an above average development of the services sector.

The productivity of agriculture is enhanced by a well-developed use of fertilisers and the traditional abundance of water, boosted since the Middle Ages by the construction (partly designed by Leonardo da Vinci) of a wide net of irrigation systems. Lower plains are characterised by fodder crops, which are mowed up to eight times a year, cereals (rice, wheat and maize) and sugar beet. Productions of the higher plains include cereals, vegetables, fruit trees and mulberries. The higher areas, up to the Prealps and Alps sectors of the north, produce fruit and wine. Cattle (with the highest density in Italy), pigs, and sheep are also raised.

The unemployment rate stood at 5.6% in 2019. Regional unemployment was one of the lowest in Italy.[67]

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unemployment rate (in %) |

3.7% | 3.4% | 3.7% | 5.3% | 5.5% | 5.7% | 7.4% | 8.0% | 8.2% | 7.9% | 7.4% | 6.4% | 6.0% | 5.6% |

Government and politics

Politics in Lombardy is framed within a system of representative democracy, where the President of the Region (Presidente della Regione) is the head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is vested in the Regional Government (Giunta Regionale) and legislative power is vested in the Regional Council (Consiglio Regionale).

Historically, the moderate Christian Democrats maintained a large majority of the popular support and the control of the most important cities and provinces from the end of the Second World War to the early 1990s. The opposition Italian Communist Party was a considerable presence only in southern Lombardy and in the working class districts of Milan; their base, however, was increasingly eroded by the rival centrist Italian Socialist Party, until eventually the Mani Pulite corruption scandal (which spread from Milan to the whole of Italy) wiped away the old political class and parties almost entirely.

This, together with the general disaffection towards the central government (considered as wasting resources to balance the budgets of the chronically underdeveloped regions of Southern Italy), led to the sudden growth of the secessionist Northern League, particularly strong in the mountain and rural areas. In the last twenty years, Lombardy stayed as a conservative stronghold, overwhelmingly voting for Silvio Berlusconi in all the six last general elections. Notwithstanding, the capital city of Milan elected progressive Giuliano Pisapia at the 2011 municipal elections and the 2013 regional elections saw a narrow victory for the center-right coalition.

On 22 October 2017 a non-binding autonomy referendum took place in Lombardy. The turnout was a low 38.3%, of which 95.3% voted in favor. The regional government of Lombardy is still under negotiation with Rome for the devolution of certain competencies.[68][69]

Administrative divisions

The region of Lombardy is divided in 11 administrative provinces, 1 metropolitan city and 1,530 communes.

| Province/Metropolitan city |

Area (km2) |

Population |

Density (inh./km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Bergamo | 2,723 | 1,108,853 | 407.2 |

| Province of Brescia | 4,784 | 1,265,077 | 264.4 |

| Province of Como | 1,288 | 599,905 | 465.7 |

| Province of Cremona | 1,772 | 361,610 | 204.4 |

| Province of Lecco | 816 | 340,251 | 416.9 |

| Province of Lodi | 782 | 229,576 | 293.5 |

| Province of Mantua | 2,339 | 414,919 | 177.3 |

| Metropolitan City of Milan | 1,575 | 3,259,835 | 2,029.7 |

| Province of Monza and Brianza | 405 | 864,557 | 2,134.7 |

| Province of Pavia | 2,965 | 548,722 | 185.1 |

| Province of Sondrio | 3,212 | 182,086 | 56.6 |

| Province of Varese | 1,211 | 890,234 | 735.1 |

Culture

Beside being an economic and industrial powerhouse, Lombardy has a rich and diverse cultural heritage. The many examples range from prehistory to the present day, through the Roman period and the Renaissance and can be found both in museums and churches that enrich cities and towns around the region. Major tourist destinations in the region include (in order of arrivals as of 2013)[71] the historic, cultural and artistic cities of Milan (4,527,889 arrivals), Bergamo (242,942), Brescia (229,710), Como (215,320), Varese (107,442), Mantua (88,902), Monza (75,839) and the lakes of Garda (429,376), Como (322,585), Iseo (123,337) and Maggiore (71,055).

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

_-_The_Last_Supper_(1495-1498).jpg.webp)

There are nine UNESCO World Heritage sites wholly or partially located in Lombardy.[72] Some of these comprise several individual objects in different locations. One of the entries has been listed as natural heritage and the others are cultural heritage sites.

At Monte San Giorgio, on the border with Swiss canton Ticino just south of Lake Lugano, a wide range of marine Triassic fossils have been found. During the Triassic period, some 240 million years ago, the area was a shallow tropical lagoon. Fossils include reptiles, fish and crustaceans and also some insects.

Two sites are of pre-historic origin. The Rock Drawings in Valcamonica date back to a period between 8000 BC and 1000 BC, covering prehistoric periods from the Epipaleolithic/Mesolithic to the Iron Age. The engravings show depictions of a wide range of topics including agricultural and war scenes alongside more abstract symbols.

The multi-centred heritage site Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps includes 111 individual objects in France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Austria and Slovenia, of which ten are located in Lombardy. Each of these objects consists of remnants of buildings erected on wooden piles in sub-alpine rivers, lakes and wetlands, built between 5000 BC and 500 BC. In general, only the submerged wooden parts have been preserved in the alluvial sediment, although in some places pile buildings have been reconstructed.

Another multi-centred site, Longobards in Italy, Places of Power (568–774 A.D.), comprises seven locations across mainland Italy which illustrate the history of the Lombard period which has given the region its name. Two of the individual sites are in the modern region of Lombardy: the fortifications (the castrum and the Torba Tower) and the church of Santa Maria foris portas ("outside the gates") with its Byzantinesque frescoes at Castelseprio, and the monastic complex of San Salvatore-Santa Giulia at Brescia. The UNESCO site of Brescia also includes the remains of its Roman forum, the best-preserved in Northern Italy.[73][74]

The Church and Dominican Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan with "The Last Supper" by Leonardo da Vinci represent architectural and painting styles of the Renaissance period of the 15th century. The towns of Mantua and Sabbioneta are also listed as a combined World Heritage site relating to this period, here focussing more on town planning aspects of the time than on architectural detail. While Mantua was rebuilt in the 15th and 16th centuries according to Renaissance principles, Sabbioneta was planned as a new town in the 16th century.

The Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy are a group of nine sites in northwest Italy, of which two are in Lombardy. The concept of holy mountains can also be found elsewhere in Europe. These sites were created as centres of pilgrimage by placing chapels in the natural landscape and were loosely modelled on the topography of Jerusalem. In Lombardy, Sacro Monte del Rosario di Varese and Sacro Monte della Beata Vergine del Soccorso, built in the early to mid-17th century, mark the architectural transition from the late Renaissance to the Baroque style.

Crespi d'Adda is a company town founded in 1878 to accommodate workers of a local textile mill. At its height, the town was home to 3,200 employees and their families.

Parco Naturalistico-Archeologico della Rocca di Manerba del Garda, a fortress of Manerba del Garda.

The Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes is mostly located in the Swiss canton Graubünden, but also extends over the border into Tirano. The site is listed because of the complex railway engineering (tunnels, viaducts and avalanche galleries) necessary to take the narrow-gauge railway across the main chain of the Alps. The two railway lines were opened in several stages between the years of 1904 and 1910.

The Venetian Works of Defence between the 16th and 17th centuries: Stato da Terra – western Stato da Mar is a transnational system of fortifications built by the Republic of Venice on its mainland domains (Stato da Terra) and its territories stretching along the Adriatic coast (Stato da Mar). This site includes the Fortified City of Bergamo.

Museums

Lombardy contains numerous museums (over 330) of different types (e.g. ethnographic, historical, technical-scientific, artistic and naturalistic) which testify to the historical-cultural and artistic development of the region. Among the most famous ones are the National Museum of Science and Technology "Leonardo da Vinci" (Milan), the Accademia Carrara (Bergamo), the Mille Miglia, the Santa Giulia Museum (both in Brescia), the Volta Temple, the Villa Olmo (both in Como), the Stradivari Museum (Cremona), the Palazzo Te (Mantua), the Museum Sacred Art of the Nativity, the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta (both in Gandino), and the Royal Villa of Monza (Monza).

Other sights

- Cathedral of Milan

- Castello Sforzesco, Milan

- Basilica di Sant'Ambrogio, Milan

- Teatro alla Scala, Milan

- Basilica of San Lorenzo, Milan

- Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio, Milan

- Brera Gallery, Milan

- Bellagio

- Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

- Santa Maria Maggiore and Cappella Colleoni, Bergamo

- The fortified Venetian walls, Bergamo

- Roman and Longobard monuments in Brescia

- Duomo Nuovo, Brescia

- Castelseprio archaeological site

- Certosa di Pavia

- Como Cathedral and Basilica of Sant'Abbondio, Como

- Duomo and Torrazzo, Cremona

- Lake Como

- Lake Garda

- Lake Iseo

- Tempio Civico della Beata Vergine Incoronata, Lodi

- Royal Villa of Monza

- San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro and San Michele Maggiore, Pavia

- Villa Toeplitz, Varese

Cuisine

Rice is popular in the region, often found in soups as well as risotti, such as "risotto alla milanese", with saffron. In the city of Monza, a popular recipe also adds pieces of sausages to the risotto. Polenta is also common throughout the region. Regional cheeses include Robiola, Crescenza, Taleggio, Gorgonzola and Grana Padano (the plains of central and southern Lombardy allow intensive cattle-raising). Butter and cream are used. Single pot dishes, which take less work to prepare, are popular. Common types of pasta include Casoncelli in Brescia and Bergamo and Pizzoccheri in Valtellina. In Mantua, festivals feature tortelli di zucca (ravioli with pumpkin filling) accompanied by melted butter and followed by turkey stuffed with chicken or other stewed meats.[75] Among typical regional desserts is Nocciolini di Canzo—dry biscuits.

Typical dishes and products

- Casoncelli

- Carpaccio di Bresaola

- Pizzoccheri (tagliatelle of buckwheat and wheat, laced with butter, green vegetables, potatoes, sage and garlic, topped with Casera cheese)

- Risotto alla milanese

- Tortelli di zucca (pumpkin-filled pasta)

- Polenta (eaten also in its taragna variant in the Northern part of the region)

- Ossobuco

- Cotoletta (cutlet) alla milanese

- Cassoeula

- Lo Spiedo Bresciano – spit roast of different cuts of meat with butter and sage

- Salamella (Italian Sausage without fennel or anise, always served grilled)

- Salame d'oca di Mortara (goose salami)

- Gorgonzola cheese

- Taleggio cheese

- Stracchino cheese

- Bitto cheese

- Rosa Camuna cheese

- Grana Padano cheese

- Mascarpone

- Panettone

- Sbrisolona cake

- Amaretti di Saronno

- Torrone

- Mostarda

Wines

- Franciacorta

- Nebbiolo red

- Bellavista

- Santi

- Nino Negri

- Bonarda Lombardy

- Inferno (Valtellina)

- Grumello (Valtellina)

- Sassella (Valtellina)

Music

Besides Milan, the region of Lombardy has 11 other provinces, most of them with equally great musical traditions. Bergamo is famous for being the birthplace of Gaetano Donizetti and home of the Teatro Donizetti; Brescia hosts the impressive 1709 Teatro Grande; Cremona is regarded as the birthplace of the commonly used violin and is home to several of the most prestigious luthiers in the world; and Mantua was one of the founding and most important cities in 16th- and 17th-century opera and classical music.

Other cities such as Lecco, Lodi, Varese and Pavia also have rich musical traditions, but Milan is the hub and centre of the Lombard musical scene. It was the workplace of Giuseppe Verdi, one of the most famous and influential opera composers of the 19th century, and boasts a variety of acclaimed theatres, such as the Piccolo Teatro and the Teatro Arcimboldi; however, the most famous is the 1778 Teatro alla Scala, one of the most important and prestigious operahouses in the world.

Language

Lombard is widely used in Lombardy, in diglossia with Italian. Lombard is a language[76] belonging to the Gallo-Italic group, within the Romance languages.[77] It is a cluster of homogeneous varieties used by at least 3,500,000 native speakers in Lombardy and some areas of neighbouring regions, notably the eastern side of Piedmont and Southern Switzerland (cantons of Ticino and Graubünden).[77]

The Lombard language should not be confused with that of the Lombards – Lombardic language, a Germanic language extinct since the Middle Ages.

Fashion

.jpg.webp)

Lombardy has always been an important centre for silk and textile production, notably the cities of Pavia, Vigevano and Cremona, but Milan is the region's most important centre for clothing and high fashion. In 2009, Milan was regarded as the world fashion capital, even surpassing New York, Paris and London.[78] Most of the major Italian fashion brands, such as Valentino, Versace, Prada, Armani and Dolce & Gabbana, are currently headquartered in the city.

Sports

The most famous sport in Lombardy, as in all Italy, is football. In fact, Lombardy is home to some of the most important football teams in the country. Considering the 2020-21 Serie A season, Lombardy hosts 3 out of 20 teams: A.C. Milan and Inter Milan (both based in Milan) and Atalanta B.C. (based in Bergamo). Other big teams of the region are Brescia Calcio, A.C. Monza and U.S. Cremonese (playing in the 2020-21 Serie B) and Calcio Lecco 1912, U.C. AlbinoLeffe, Como 1907, Aurora Pro Patria 1919, A.C. Renate, A.S. Giana Erminio, S.S.D. Pro Sesto and U.S. Pergolettese 1932 (playing in the 2020-21 Serie C).

The region's city Milan will host the 2026 Winter Olympics alongside Cortina d'Ampezzo. The Autodromo Nazionale di Monza, located outside of Milan, hosts the Formula One Italian Grand Prix.

Twinning and covenants

See also

References

- "Lombardia, Lombardia, presentato l'inno della Regione". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 22 December 2014.

- "Monthly demographic balance, January–June 2013". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018" (Press release). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- "OECD Statistics". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Lombardy". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "Lombardy". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "EUROPA Press Releases – Regional GDP per inhabitant in the EU27, GDP per inhabitant in 2006 ranged from 25% of the EU27 average in Nord-Est in Romania to 336% in Inner London". Europa (web portal). 19 February 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- OECD Data Synthesis.

- Eurostat – Functional urban areas Archived 16 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- List of World Heritage Sites by country.

- Partridge, Eric (2009). Origins: an etymological dictionary of modern English ([Paperback ed.] ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415474337.

- "Regional Statistical Yearbook: average rainfall, yearly and ten-year average, Lombardy and its provinces". Regione Lombardia. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Rock Drawings in Valcamonica – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Piero Adorno, Mesolitico e Neolitico, p. 16.

- "Introduzione all'arte rupestre della Valcamonica". Archeocamuni.it (in Italian). Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- Maciamo Hay (July 2013). "Genetic History of the Italians". Eupedia. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Storia di Milano ::: Gian Giacomo Mora". Storiadimilano.it.

- "Italy announces quarantine affecting quarter of population". CNBC. 8 March 2020.

- Business, Hanna Ziady, CNN. "Italy just locked down the world's 8th biggest economy. A deep recession looms". CNN.

- "Italy's worst-hit region introduces stricter measures". 22 March 2020 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Anger as Italy slowly emerges from long Covid-19 lockdown | Italy | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com.

- "Foreign Citizens. Resident Population by sex and citizenship on 31st December 2017". National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Regional Statistical Yearbook 2014" (PDF). Regione Lombardia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Dati Istat consultati il 15 giugno 2016. Nota: per visualizzare i dati occorre selezionare nella colonna a destra la voce Conti nazionali, Conti e aggregati economici territoriali, Valori procapite (euro) e in tabella selezionare la voce prodotto interno lordo ai prezzi di mercato per abitante (edizione novembre 2015) valutazione a prezzi correnti.

- OECD. "Competitive Cities in the Global Economy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- "Italian official: Azerbaijan has obtained impressive achievements [PHOTO]". AzerNews.az. 6 December 2018.

- "Design, in Lombardia crescono gli scambi con l'Austria". Giornalemetropolitano.it. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Accordo IED-Camera Commercio Austriaca, vice presidente Regione: nuova opportunità di sviluppo".

- "Expo Milano – Regione Lombardia". Ambvienna.esteri.it. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Milano, Attilio Fontana incontra l'ambasciatore francese: "Distendere gli animi tra Italia e Francia"". Corriere della Sera. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Regione Lombardia, il presidente Fontana riceve il ministro degli affari esteri ungherese". BresciaToday.

- "Ungheria, Fontana riceve ministro Esteri a Palazzo Lombardia". 5 December 2018.

- "Il Console Generale è stato accolto dal Presidente della Regione di Lombardia – Consolato Generale di Ungheria Milano". Milano.mfa.gov.hu. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Lecco: cresce l'export sul mercato ungherese – Tecnologie del Filo". Tecnologiedelfilo.it. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Delegazione Ungherese in visita di studio in Italia – :. ERSAF – Ente Regionale per i Servizi all' Agricoltura e alle Foreste:Regione Lombardia ". Ersaf.lombardia.it. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "[Comunicato stampa Giunta regionale Lombardia] CANTON TICINO, FONTANA E ASSESSORI INCONTRANO DELEGAZIONE SVIZZERA:SUL TAVOLO INFRASTRUTTURE, TRASPORTI E AMBIENTE". Regioni.it. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Rivedere l'accordo fiscale". Prealpina.it. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Fontana: "I rapporti con la Svizzera vanno intensificati"". Varesenews.it. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- swissinfo.ch, S. W. I.; Corporation, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting. "GR: Milano, trasporto transfrontaliero, incontro Grigioni-Lombardia". TVSvizzera.

- "Tra Lombardia e Grigioni massima collaborazione, anche per le Olimpiadi". VareseNews. 24 September 2019.

- "Political and institutional relations". MRIF – Ministère des Relations internationales et de la Francophonie. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Baviera partner ship Lombardia". Newsfood.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Incontro del Consiglio regionale lombardo con delegazione parlamentare della Bassa Sassonia". Giornalemetropolitano.it. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "KUNA : Kuwait works to boost cooperation with Italy's northern provinces, Lombardy - Politics - 13/07/2018". 15 July 2018. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- "Province of Zuid-Holland intensifies water cooperation with Lombardy, Italy | Dutch Water Sector". www.dutchwatersector.com.

- "Tavola rotonda Lombardia-Russia, Fontana: "Collaborazione importante per il nostro territorio"". BresciaToday.

- Casqueiro, Javier (4 July 2018). "Borrell ordena a todas las embajadas responder a las "lindezas" independentistas contra España". El País. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Action Group 1". EUSALP. 17 November 2016.

- "Presidenza Italiana EUSALP 2019".

- "Il timone di Eusalp passa dal Tirolo alla Lombardia". 22 November 2018.

- "Chi siamo – Arge Alp". it.argealp.org.

- "Olimpiadi 2026 e Fondi di confine, si rafforza la collaborazione fra Trentino e Lombardia". 2 May 2019.

- Trento, Redazione (4 May 2019). "Trentino e Lombardia: si rafforza la sinergia per le Olimpiadi 2026".

- "www.ladigetto.it – Trentino e Lombardia: si rafforza la collaborazione". ladigetto.it.

- "PAT * Trentino e Lombardia: "Incontro a Milano tra i presidenti Fugatti e Fontana, si rafforza la collaborazione"". 2 May 2019.

- https://www.askanews.it/cronaca/2019/05/02/fontana-incontra-fugatti-collaborazione-tra-lombardia-e-trentino-pn_20190502_00154/>

- "Regione del Veneto". Regione del Veneto.

- "Lombardia Quotidiano". Lombardia Quotidiano. 19 October 2018.

- "Lombardia e Friuli Venezia Giulia due regioni a confronto". valtellinanews.it.

- "Parco dello Stelvio, intesa Trentino, Alto Adige e Lombardia sulla biodiversità – Cronaca". Trentino.

- SPA, Südtiroler Informatik AG | Informatica Alto Adige. "News & Media | Provincia autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige". Amministrazione provinciale.

- "Lombardia, Veneto e Trentino: "Regole comuni per la pesca su tutto il lago di Garda"". l'Adige.it. 4 April 2019.

- "Il Programma Central Europe 2014-2020".

- "Discover Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE". Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE.

- "Regional Unemployment by NUTS2 Region". Eurostat.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Giorno, Il. "Autonomia Lombardia, Fontana: consegnato al ministro dossier con le prime 15 materie – Il Giorno". Il Giorno. Italy. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Lomabrdy (Italy). Resident population on 31 December 2019 by territory". tuttitalia.it. Istat. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "RSY Lombardia-Arrivals and nights spent by guests in accommodation establishments, by type of resort and by type of establishment. Total accommodation establishments. Part III Tourist resort. Year 2013". Asr-lombardia.it. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- "World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Italia langobardorum, la rete dei siti Longobardi italiani iscritta nella Lista del Patrimonio Mondiale dell'UNESCO" [Italia langobardorum, the network of the Italian Longobards sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List]. Beniculturali.it (in Italian). Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "THE LONGOBARDS IN ITALY. PLACES OF THE POWER (568–774 A.D.). NOMINATION FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Piras, 87.

- "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: LMO".

Identifier: LMO / Name: Lombard / Status: Active / Code set: 639-3 / Scope: Individual / Type: Living

- Jones, Mary C.; Soria, Claudia (2015). "Assessing the effect of official recognition on the vitality of endangered languages: a case of study from Italy". Policy and Planning for Endangered Languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781316352410.

Lombard (Lumbard, ISO 639-9 lmo) is a cluster of essentially homogeneous varieties (Tamburelli 2014: 9) belonging to the Gallo-Italic group. It is spoken in the Italian region of Lombardy, in the Novara province of Piedmont, and in Switzerland. Mutual intelligibility between speakers of Lombard and monolingual Italian speakers has been reported as very low (Tamburelli 2014). Although some Lombard varieties, Milanese in particular, enjoy a rather long and prestigious literary tradition, Lombard is now mostly used in informal domains. According to Ethnologue, Piedmontese and Lombard are spoken by between 1,600,000 and 2,000,000 speakers and around 3,500,000 speakers, respectively. These are very high figures for languages that have never been recognised officially nor systematically taught in school

- "The Global Language Monitor " Fashion". Languagemonitor.com. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

Further reading

- Cochrane, Eric. Historians and historiography in the Italian Renaissance (U of Chicago Press, 1981).

- Conca Messina, Silvia A., and Catia Brilli. "Agriculture and nobility in Lombardy. Land, management and innovation (1815-1861)." Business History (2019): 1-25.

- de Klerck, Bram. The Brothers Campi: Images and Devotion. Religious Painting in Sixteenth-Century Lombardy (Amsterdam UP. 1999).

- Di Tullio, Matteo. "Cooperating in time of crisis: war, commons, and inequality in Renaissance Lombardy." Economic History Review 71.1 (2018): 82-105.

- Di Tullio, Matteo. The wealth of communities: war, resources and cooperation in Renaissance Lombardy (Ashgate, 2014).

- Gamberini, Andrea. The Clash of Legitimacies: The State-Building Process in Late Medieval Lombardy (2018) online

- Greenfield, Kent Roberts. Economics and liberalism in the Risorgimento: a study of nationalism in Lombardy, 1814-1848 (1934).

- Klang, Daniel M. "Cesare Beccaria and the clash between jurisprudence and political economy in eighteenth-century Lombardy." Canadian journal of history 23.3 (1988): 305–336.

- Klang, Daniel M. "The problem of lease farming in eighteenth-century Piedmont and Lombardy." Agricultural history 76.3 (2002): 578-603 online.

- Klang, Daniel M. Tax reform in eighteenth century Lombardy (1977) online

- Messina, Silvia A. Conca. Cotton Enterprises: Networks and Strategies: Lombardy in the Industrial Revolution, 1815-1860 (2018) excerpt

- Pyle, Cynthia Munro. Milan and Lombardy in the Renaissance: Essays in cultural history (1997).

- Sella, Domenico. Crisis and continuity : the economy of Spanish Lombardy in the seventeenth century (1979) online

- Soresina, Marco. "Images of Lombardy in historiography." Modern Italy 16.1 (2011): 67–85.

- Storrs, Christopher. "The Army of Lombardy and the Resilience of Spanish Power in Italy in the Reign of Carlos II (1665-1700) (Part I)." War in History 4.4 (1997): 371–397.

Guide books

- Daverio, Philippe. Lombardy: 127 Destinations For Discovering Art, History, and Beauty (2016) guide book. excerpt

- Macadam, Alta, and Annabel Barber. Blue Guide Lombardy, Milan & the Italian Lakes (2020) excerpt

- Williams Jr., Egerton R. Lombard Towns in Italy; Or, The Cities of Ancient Lombardy (1914) online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lombardy. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lombardy. |

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)