Red-tailed phascogale

The red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura), also known as the red-tailed wambenger or red-tailed mousesack, is a small carnivorous marsupial found in Central and Western Australia. It is closely related to the brush-tailed phascogale (Phascogale tapoatafa), but is smaller and browner.

| Red-tailed phascogale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | Dasyuridae |

| Genus: | Phascogale |

| Species: | P. calura |

| Binomial name | |

| Phascogale calura Gould, 1844 | |

| |

| Red-tailed phascogale range | |

Taxonomy

The red-tailed phascogale is one of three members of the phascogale genus, the others being the brush-tailed phascogale (P. tapoatafa) and the Northern brush-tailed phascogale (P. pirata). The species was described in 1844 by naturalist and artist John Gould. Its scientific name means "beautiful-tailed pouched-weasel".[3]

Description

.jpg.webp)

The red-tailed phascogale is smaller and browner than its close relative the brush-tailed phascogale. As in the brush-tailed phascogale, male red-tailed phascogales die following their first mating as a result of stress-related diseases.[4] Males rarely live past 11.5 months, although females can live to three years old. In captivity males and females can survive up to five years.[5][6] An arboreal species, the red-tailed phascogale has a varied diet, and can feed on insects and spiders, but also small birds and small mammals, notably the house mouse (Mus musculus), which has become ubiquitous in the landscape since its introduction by Europeans;[7][8] it does not drink as its water is metabolised through its food.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The red-tailed phascogale was formerly widespread throughout central and western Australia but is now restricted to the southern Western Australian wheatbelt,[9] It is found in dense and tall climax vegetation, and appears to prefer those containing the Wandoo (Eucalyptus wandoo) and the rock sheoak (Allocasuarina huegeliana), as it has developed a resistance to the fluoroacetate the plants produce that is lethal to livestock.[3] Most native animals have a resistance to this fluoracetate, but introduced species, like the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), do not, so it has been suggested that the red-tailed phascogale's survival in these areas could be attributed to this chemical.[3] The species was reintroduced to the Wadderin Sanctuary in the central wheatbelt of Western Australia in 2009. Recent conservation efforts in Central Australia have paid off, and 30 were released at the remote Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary in June 2020 after a captive breeding program at the Alice Springs Desert Park. They were bred from a small group taken from the wild in Western Australia, after their delicate breeding cycle was carefully managed. The animals were microchipped before release, and will be tracked for their whole lives.[10]

Conservation status

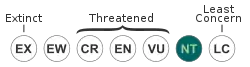

The animal is classified as near threatened by the IUCN Red List and endangered by the Australian EPBC Act.[3]

Model species

The species is used as a model species in research. Studies have been conducted on behavioural thermoregulation and have indicated they bask to reduce their energy demands.[11] Captive nutrition trials found red-tailed phascogales consume up to 39% of their body mass in food per day and their daily maintenance energy requirements are approximately 954 kJ kg0.75day−1.[12] Like many other mammals their food intake during lactation changes to meet the increasing demands of the young.[13]

Most notably the red-tailed phascogale has been used to study the marsupial immune system and the development of their immune tissues.[14] They have an active complement system,[15] like other marsupials,[16] and the expression levels of complement components vary in developing young.[17] The serum of red-tailed phascogales has been shown to have antimicrobial properties against some bacterial species.[18]

Red-tailed phascogales also express T-cell receptors and co-receptors,[19] major histocompatibility complex,[20] and interleukin-6 and its receptor.[21]

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Burbrudge, A. A.; Woinarski, J. (2019). "Phascogale calura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T16888A21944219. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T16888A21944219.en.

- Bradley, A. J. (1995), "Red-tailed Phascogale", in Strahan, Ronald (ed.), The Mammals of Australia, Reed Books, pp. 102–103, ISBN 978-0-7301-0484-1

- Menkhorst, Peter; Knight, Frank (2001), A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia, Oxford University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-19-550870-3

- Bradley, A. J., Foster, W. K., and Taggart, D. A. (2008). Red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura). In ‘The Mammals of Australia’. (Eds S. Van Dyck and R. Strahan.) pp. 101–102. (New Holland: Sydney.)

- Stannard, H.; Borthwick, C.; Ong, O.; Old, J. (2013). "Longevity and breeding in the red-tailed phascogale Phascogale calura". Australian Mammalogy. 35 (2): 217–219. doi:10.1071/AM12042. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AM12042

- Kitchener, D.J., 1981. Breeding, diet and habitat preference of Phascogale calura (Gould, 1844)(Marsupialia: Dasyuridae) in the southern wheatbelt, Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, 9, pp.173-186.

- Stannard, H.J., Caton, W. and Old, J.M., 2010. The diet of red‐tailed phascogales in a trial translocation at Alice Springs Desert Park, Northern Territory, Australia. Journal of Zoology, 280(4), pp.326-331. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00658.x

- Short, J.; Hide, A (2012). "Distribution and status of the red-tailed phascogale Phascogale calura". Australian Mammalogy. 34: 88–99. doi:10.1071/AM11017.

- Beavan, Katrina (23 June 2020). "Red-tailed phascogales return to Central Australian landscape for the first time in decades". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Stannard, H.; Fabian, M.; Old, J. (2015). "To bask or not to bask: Behavioural thermoregulation in two species of dasyurid, Phascogale calura and Antechinomys laniger". Journal of Thermal Biology. 53: 66–71. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2015.08.012. PMID 26590457.

- Stannard, H.J. and Old, J.M., 2012. Digestibility of feeding regimes of the red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura) and the kultarr (Antechinomys laniger) in captivity. Australian Journal of Zoology, 59(4), pp.257-263. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1071/ZO11069

- Stannard, H.; Old, J. (2015). "Changes to food intake and nutrition of female red-tailed phascogales (Phascogale calura) during late lactation". Physiology and Behavior. 151: 398–403. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.08.012. PMID 26260432. S2CID 6485078.

- Borthwick, C.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2016). "Histological development of the immune tissues of a marsupial, the red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura)". Anatomical Record. 299 (2): 207–219. doi:10.1002/ar.23297. PMID 26599205. S2CID 26070813.

- Ong, O.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2016). "Preliminary genomic survey and sequence analysis of the complement system in non-eutherian mammals". Australian Mammalogy. 38: 80–90. doi:10.1071/AM15036.

- Ong, O.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2015). "Detection of an active complement system in red-tailed phascogales (Phascogale calura)". Comparative Clinical Pathology. 24 (6): 1527–1534. doi:10.1007/s00580-015-2111-2. S2CID 29065218.

- Ong, O.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2016). "Sequences and expression of pathway-specific complement components in developing red-tailed phascogale Phascogale calura". Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 65: 314–320. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2016.08.003. PMID 27514577.

- Ong, O.; Green-Barber, J.; Kanuri, A.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2017). "Antimicrobial activity of red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura) serum". Comparative Immunology Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 51: 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.cimid.2017.03.001. PMID 28504094.

- Borthwick, C.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2018). "Molecular identification and gene expression profiles of the T-cell receptors and co-receptors in developing red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura) pouch young". Molecular Immunology. 101: 268–275. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2018.07.005. PMID 30029061. S2CID 51706551.

- Hermsen, E.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2016). "MHC Class II in the red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura)". Australian Mammalogy. 39: 28–32. doi:10.1071/AM16002.

- Borthwick, C.; McAllan, B.; Young, L.; Old, J. (2016). "Identification of the mRNA encoding interleukin-6 and its receptor, interleukin-6 receptor α, in five marsupial species". Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 65: 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2016.07.008. PMID 27431929.

External links

- AustralianFauna.com

- Australian Department of Environment and Heritage Species Profiles, features distribution map