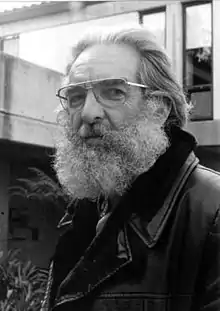

Reyner Banham

Peter Reyner Banham, FRIBA (2 March 1922 – 19 March 1988) was an English architectural critic and writer best known for his theoretical treatise Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960) and for his 1971 book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies.[1] In the latter he categorized the Los Angeles experience into four ecological models (Surfurbia, Foothills, The Plains of Id, and Autopia) and explored the distinct architectural cultures of each. A frequent visitor to the United States from the early 1960s, he relocated there in 1976.

Reyner Banham FRIBA | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Peter Reyner Banham 2 March 1922 Norwich, England |

| Died | 19 March 1988 (aged 66) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Courtauld Institute of Art |

| Occupation | Architectural historian |

| Known for | New Brutalism |

Notable work | Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960) The New Brutalism (1966) Los Angeles: the Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971) |

Early life and education

He was born in Norwich, England to Percy Banham, a gas engineer, and Violet Frances Maud Reyner. He was educated at Norwich School and gained an engineering scholarship with the Bristol Aeroplane Company, where he spent much of the Second World War. In Norwich he gave art lectures, wrote reviews for the local paper and was involved with the Maddermarket Theatre.[2] In 1949 Banham entered the Courtauld Institute of Art in London where he studied under Anthony Blunt, Sigfried Giedion and Nikolaus Pevsner.[3] Pevsner, who was his doctoral supervisor, invited Banham to study the history of modern architecture, following his own work Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936).

Career

In 1952 Banham began working for the Architectural Review,[2] having previously written regular exhibition reviews for ArtReview, then titled Art News and Review.[4] Banham also had connections with the Independent Group, the 1956 This Is Tomorrow art exhibition – considered by many to the birth of pop art – and the thinking of the Smithsons and of James Stirling, on the 'New Brutalism', which he documented in his 1966 book The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? But before this in Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, he cut across mentor Pevsner's main theories, linking modernism to build structures in which the 'functionalism' was actually subject to formal structures. Later, he wrote a Guide to Modern Architecture (1962, later titled Age of the Masters, a Personal View of Modern Architecture). Banham predicted a "second age" of the machine and mass consumption. The Architecture of Well-Tempered Environment (1969) follows Giedion's Mechanization Takes Command (1948), putting the development of technologies such as electricity and air conditioning ahead of the classic account of structures. In the 1960s, Cedric Price, Peter Cook, and the Archigram group also found this to be an absorbing arena of thought.

Green thinking (Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies) and then the oil shock of 1973 affected him. The 'postmodern' was for him uneasy, and he evolved into the conscience of postwar British architecture. He broke with utopian and technical formalism. Scenes in America Deserta (1982) talks of open spaces and his anticipation of a 'modern' future. In A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture, 1900–1925 (1986) Banham demonstrates the influence of American grain elevators and "Daylight" factories on the Bauhaus and other modernist projects in Europe.

Teaching

As a professor, Banham taught at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London and the State University of New York (SUNY) Buffalo from 1976 to 1980,[5] and through the 1980s at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He had been appointed the Sheldon H. Solow Professor of the History of Architecture at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University shortly before his death, but he never taught there.

Awards and tributes

He was featured in the short documentary Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles; in his book on Los Angeles, Banham said that he learned to drive so he could read the city in the original.

In 1988 he was awarded the Sir Misha Black award and was added to the College of Medallists.[6]

Criticism

In 2003, Nigel Whiteley published a critical biography of Banham, Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future,[7] in which he gives an in-depth overview of Banham's work and ideas.

Bibliography

- Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. Praeger. 1960. Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Second ed.). Praeger. 1967.

- Guide to Modern Architecture. Architectural Press. 1962. ISBN 978-0-85139-261-5.

- The New Brutalism. Architectural Press. 1966.

- Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment. Architectural Press. 1969. ISBN 978-0-85139-073-4. Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment (Second, revised ed.). Architectural Press. 1984. ISBN 978-0-85139-749-8.

- Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. Harper and Row. 1971. ISBN 978-0-7139-0209-9.

- Megastructure. Thames and Hudson. 1976.

- Scenes in America Deserta. Thames and Hudson. 1982. ISBN 978-0-500-01292-5.

- A Concrete Atlantis: US Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture. MIT Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0-262-52124-6.

References

- Goldberger, Paul (22 March 1988). "Reyner Banham, Architectural Critic, Dies at 66". The New York Times.

- Sutherland Lyall (2004; online edn, May 2008). "Banham, (Peter) Reyner (1922–1988)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 January 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Dictionary of Art Historians. "Banham, [Peter] Reyner, "Peter"". Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Jacob, Sam. "From Commons to Ruins". Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- SUNY, School of Architecture and Planning

- "The Sir Misha Black Medal | Misha Black Awards". mishablackawards.org.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Whiteley, Nigel (2003). Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73165-2.

External links

- Julian Cooper (director), Malcolm Brown (producer) (1972). Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles. BBC. OCLC 748594258. Retrieved 31 August 2013. 52 minute episode from the BBC series One pair of eyes. Banham narrates a video tour of Los Angeles; the program incorporates interviews with authors Henry Miller and Norman Mailer, among others.

- "Reyner Banham's Unwarranted Apology". solarhousehistory.com.

- "Reyner Banham on Solar Heating". solarhousehistory.com.

- Reyner Banham Papers at the Getty Research Institute