Richard Field (printer)

Richard Field (or Feild) (1561–1624) was a printer and publisher in Elizabethan London, best known for his close association with the poems of William Shakespeare, with whom he grew up in Stratford-upon-Avon.[1]

Life and career

Field's family lived on Bridge Street, Stratford-upon-Avon, close to the Shakespeare's house on Henley Street. His father was a tanner. It is generally accepted that Shakespeare and Field knew each other in Stratford, since they were similar in age and their fathers were in similar businesses (tanner and glover). After Field's father Henry died in August 1592, William's father John Shakespeare was one of the local officials charged with the appraisal of the deceased man's property.

In 1579 Richard Field began an apprenticeship with the London printers George Bishop and Thomas Vautrollier. Vautrollier died in 1587. In 1588, Field collaborated with Jacqueline Vautrollier, Thomas Vautrollier's widow and a printer in her own right, on The copie of a letter sent out of England to Don Bernardin Mendoza declaring the state of England. This piece of Protestant propaganda was the first work to bear Field's name. Field went on to marry Jacqueline in 1589. He succeeded to his former master's business, "one of the best in London."[2] Field's shop was in the Blackfriars area of London, near Ludgate. He regularly printed works for the most highly regarded publishers in London, including William Ponsonby and Edward Blount. In 1592 his brother, Jasper Field, joined Richard's business as an apprentice.

Field's Protestantism led him to publish a number of Spanish-language Protestant works for sale in Catholic Spain, under the name "Ricardo del Campo." Examples include a translation of Calvin's reformed catechism, Catecismo que significa forma de instrucción, que contiene los principios de la religión de dios, util y necessario para todo fiel Christiano : compuesto en manera de dialogue, dónde pregunta el maestro, y responde el discípulo (1596). His Spanish works included a number which claimed to be written by Cipriano de Valera, including Dos tratados. El primero es del Papa y de su autoridad colegiado de su vida y dotrina, y de lo que los doctores y concilios antiguos y la misma sagrada Escritura enseñan. El segundo es de la Missa recopilado de los doctores y concilios y de la sagrada Escritura (1599) and a Spanish New Testament (1596).

For his title pages, Field adopted an Aldine device, an anchor with the Latin motto Anchora Spei, "anchor of hope," which previously belonged to the Vautrollier.

In Field's era, the trades of printer and publisher were to some significant degree separate activities: booksellers acted as publishers and commissioned printers to do the requisite printing. Field concentrated more on printing than publishing: of the roughly 295 books he printed in his career, he was publisher of perhaps 112, while the rest were published by other stationers.[3] When, for example, Andrew Wise published Thomas Campion's Observations in the Art of English Poesy in 1602, the volume was printed by Field.

Field rose to be one of the 22 master printers of the Stationers Company. From 1615 on he kept his shop in Wood Street, near his home. Field had a number of apprentices, one being George Miller. After Field's death in 1624, his business passed to the partners Richard Badger and George Miller, who continued to employ the Aldine device.

Shakespeare's poems

Field is best remembered for printing the early editions of three of Shakespeare's non-dramatic poems:

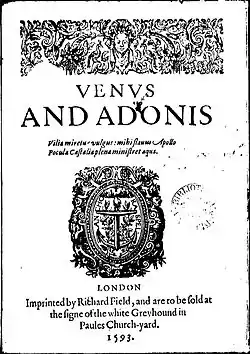

- Venus and Adonis – Field printed the first four editions of the narrative poem, the quartos of 1593 and 1594 and the octavos of 1595 and 1596.

- The Rape of Lucrece – Field printed the first quarto edition of 1594.

- The Phoenix and the Turtle – working for Edward Blount, Field printed the 1601 first quarto edition of the poem Love's Martyr by Robert Chester. In addition to Chester's poem, the volume contained short poems by other hands, including Shakespeare's work.

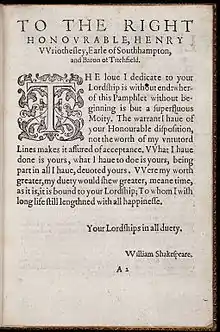

In contrast to the early printed editions of Shakespeare's plays, Field's texts for the two narrative poems meet a high standard of quality. Scholars have sometimes supposed Shakespeare's direct involvement: "The two early poems, both carefully printed by Field, are probably the only works the publication of which Shakespeare supervised."[4] Others, however, have disputed the idea of the poet's personal involvement, arguing that Field, "a highly efficient printer with a reputation for honesty and scrupulousness," could have produced the high-quality texts on his own.[5]

Field entered Venus and Adonis into the Stationers' Register on 18 April 1593, and published as well as printed the first two editions, but on 25 June 1594 he transferred the rights to the poem to bookseller John Harrison ("the Elder"). Harrison published Lucrece as well as future editions of Venus, and sold the books from his shop at the sign of the White Greyhound in St. Paul's Churchyard. Harrison later published editions of Lucrece that were printed by other printers.[6]

Other connections

Another association between Shakespeare and Field has been theorised. It has often been noticed that many of the texts that Shakespeare used as sources for his plays were products of the Vautrollier/Field printshop. These texts include Thomas North's translation of Plutarch, Sir John Harington's translation of Orlando Furioso, Robert Greene's Pandosto, the works of Ovid, and possibly Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles. Since Field would have kept a copy of each of these books in his shop, it has been theorised that Shakespeare used Field's shop as a library during his early career.[7] James Shapiro argues that the influence of Plutarch was especially significant in Shakespeare's mid-career and that he "probably worked from a copy of Plutarch given, or lent him, by Field, an expensive and beautiful folio that cost a couple of pounds".[8]

Richard and Jacqueline Field lived on Wood Street in the parish of St. Olave in the early 17th century; Shakespeare moved in with the Mountjoy family in nearby Silver Street in 1602. Mrs. Field and the Mountjoys were members of the community of Huguenot exiles in London, and likely knew each other on that basis – a further probable connection between Shakespeare and the Fields.[9]

Cymbeline

There is no direct evidence for a connection between Shakespeare and Field after 1601, but an indirect connection exists in a reference in Shakespeare's Cymbeline, believed to have been written around 1610. In IV,ii,377 of that play, Imogen gives the decapitated corpse of Cloten the name "Richard du Champ," French for Richard Field. (When printing Spanish texts, Field called himself "Ricardo del Campo.")[8] Shakespeare's reason for giving his friend and colleague's name to the headless corpse of a villain is a matter of speculation. However, at this point in the play Imogen believes the body to be that of her husband Posthumus. When discovered (dressed as a young man) embracing the corpse, she dissembles by inventing the imaginary "du Champ", referring to him as "a very valiant Briton and a good", calling herself his devoted servant. For this reason the name is typically interpreted as an affectionate compliment to Field.[10]

References

- Kirwood, A. E. M. "Richard Field, Printer, 1589–1624." The Library 12 (1931), pp. 1–35.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1864. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 165.

- Kirkwood, p. 13.

- Halliday, p. 165.

- Shakespeare, William. The Poems. John Roe, ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006; p. 296.

- Halliday, pp. 165, 207, 402, 513.

- Stopes, Charlotte. Shakespeare's Warwickshire Contemporaries. Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare Head Press, 1907.

- Shapiro, James. A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599. New York, HarperCollins, 2005; p. 133.

- Pogue, p. 24.

- Ros King, Cymbeline: constructions of Britain, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, p.89.; Laurie E. Maguire, Shakespeare's Names, Oxford University Press, 2007, p.35.