Rimini protocol

The Rimini Protocol is a proposal made by the geologist Colin Campbell. It is intended to stabilise oil prices and minimise the effects of peak oil. It is named after the XXIX. Annual Conference The Economics of the Noble Path: Fraternal Rights, the Convival Society, Fair Shares for All of the Pio Manzù International Research Centre in Rimini, Italy on 18-20 October, 2003, where Campbell presented his idea of an oil depletion protocol.[1] A few months later, he published together with Kjell Aleklett, the head of the Uppsala Hydrocarbon Depletion Study Group, a slightly refined text under the name Uppsala Protocol.[2]

Basic mechanism

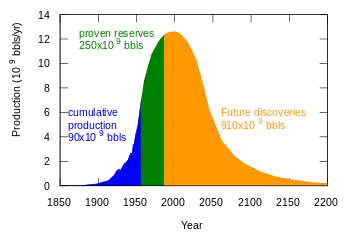

To ease peak oil effects and to manage the long decline in the second half of the oil era, producing countries would not produce oil in excess of their present national depletion rate: i.e., roughly speaking, the oil used or exported must equal the oil produced or imported. Furthermore, it would be required that importing nations stabilize their imports at existing levels and match their consumption to the global decline rate. Consuming nations should actively reduce oil consumption each year by the global decline rate (then estimated at ~2.6%). This would have the effect of keeping world prices reasonable without price shocks and let Third World countries afford their oil imports.[3]

The protocol consists - beyond introducing whereas considerations and a list of objectives - the following provisions:

No country shall produce oil at above its current Depletion Rate, such being defined as annual production as a percentage of the estimated amount left to produce;

Each importing country shall reduce its imports to match the current World Depletion Rate, deducting any indigenous production.— Colin J. Campbell, Proposal at the 2003 Pio Manzu Conference, and to be the central theme of the 2005 Pio Manzu Conference, Rimini, Italy[4]

Campbell's own words

Campbell also stresses the need for outdated principles of economic growth to be surpassed. He states (May 2004): "the economic fundamentalists ... have these really outdated economic principles inherited from the Industrial Revolution, when the world was indeed large and the scope for Man’s activities were at that time more or less infinite. ... these economic principles ... are very short term in their nature ... these people who say that there can be no shortage in an open market and their battle cry is liberalize markets - these people have become really the enemy ..."[5] As such, Campbell strongly criticises those who accelerate the peak oil crisis, rather than taking action to curtail it as he recommends.

Campbell substantiates the prediction of the urgent forthcoming "peak oil" crisis by making reference to Saudi Arabia, a nation covering a geographic region wherein there is a huge concentration of oil. Campbell hypothesises: "I think even the Sauds would always develop the larger ones first. So the biggest field in the world is Ghawar, with 80 billion in it perhaps, you step outside from this trend to Safaniya with 35 perhaps, Hanifah about 12 and Shaybah 15, and you come on down. If they develop the big ones first, which one must assume they did, you are down to well, still nice oilfields but of a modest scale, and so I suppose the other discoveries they made have made are smaller by orders of magnitude ... it’s quite evident that this doesn’t come close to the past."[5]

Political support

Support for the Rimini Protocol has even been found in retired politicians. Yves Cochet, the former Minister of Environment of France and author of Pétrole apocalypse, has been supportive. The closest endorsement of the Rimini Protocol by politicians can be found in The Oil Depletion Protocol: A Plan to Avert Oil Wars, Terrorism and Economic Collapse (Heinberg, 2006). Its author states in the preface that his book was written with the “silent collaboration” (p. XI) of the aforementioned Colin Campbell, the petroleum geologist who first proposed the Rimini Protocol alongside Kjell Aleklett. The list of former politicians who endorse this book (and, arguably, by extension, the Rimini Protocol) are as follows: Andrew McNamara, MP, Parliament of Queensland, Australia; Roscoe G. Bartlett, U.S. Congressman belonging to the Republican Party; and Michael Meacher, former member of the U.K. parliament belonging to the Labour Party.[6] In regard thereto, Campbell proclaims: "And then ... you have the people I call the Renegades. These are senior politicians who are now out of office and being freed from the system, are able to tell the truth. And some of them do."[5]

References

- Hall, Charles A. S.; Ramírez-Pascualli, Carlos A. (2013). The First Half of the Age of Oil – An Exploration of the Work of Colin Campbell and Jean Laherrère. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 97ff. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6064-0. ISBN 978-1-4614-6063-3.

- Campbell, Colin; Aleklett, Kjell (2004-06-07). "The Uppsala Protocol". peakoil.net. Uppsala Hydrocarbon Depletion Study Group. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Heinberg, Richard (2006). The Oil Depletion Protocol – A Plan to Avert Oil Wars, Terrorism and Economic Collapse. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86571-563-9.

- Campbell, Colin J. (2005-08-17). "THE RIMINI PROTOCOL an Oil Depletion Protocol" (PDF). oilcrashmovie.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Darley, Julian (2004-06-10). "Colin Campbell interviewed after ASPO". resilience.org. Post Carbon Institute. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

Filmed on 27th May 2004 after The APSO 2004 Conference [..] Colin Campbell speaks with Julian Darley in Berlin on The ASPO 2004 Conference, the Rimini Protocol, Shell and Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.

- "Oil Depletion Protocol – Endorsements". Richard Heinberg. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

Further reading

- Campbell, Colin; Laherrère, Jean (March 1998). "The End of Cheap Oil" (PDF). Scientific American. 278 (3): 78–84. Bibcode:1998SciAm.278c..78C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0398-78. ISSN 0036-8733. Retrieved 2020-06-12. Archived 2018-06-03 at the Wayback Machine