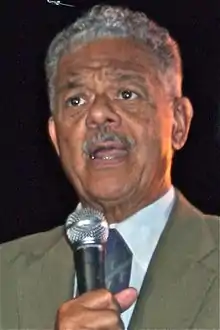

Robert C. Farrell

Robert C. Farrell (born 1936) is a politician who was a member of the Los Angeles City Council from 1974 until 1991. Previously, he was a journalist and newspaper publisher.

Robert C. Farrell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Los Angeles City Council from the 8th District | |

| In office 1974–1991 | |

| Preceded by | Billy G. Mills |

| Succeeded by | Mark Ridley-Thomas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1, 1936 Natchez, Mississippi |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Residence | Los Angeles, California |

Biography

Farrell was born in Natchez, Mississippi, on October 1, 1936, and moved with his family to New Orleans and Newark, New Jersey, before settling in Los Angeles, where he attended Los Angeles High School, graduating in 1954. He enlisted in the Navy and in 1956 was promoted to midshipman. After his service, he received a Navy scholarship to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree in Near Eastern Studies at UCLA in 1961. He returned to UCLA in 1962, where he studied journalism.

Farrell began his journalistic career as a reporter for the black-oriented California Eagle newspaper and on the Los Angeles Sentinel. He was also a correspondent for Jet magazine. In 1966 he published his own newspaper in Watts, the Star-Review. He also helped research and prepare a UCLA report on hard-core unemployment in South Los Angeles.[1]

Farrell married Willie Mae Reese in October 30, 1965. They divorced in August 1974. There is one daughter from this union, Mia Ann Farrell. Farrell then married Essiebea L. Hayes and they were separated in April 1984. They divorced in September 1986. There is one daughter from this union, Kongit Arlicekathinia Farrell. Farrell is now happily married to Windy Barnes-Farrell. They will soon celebrate 30 years of marriage.[2][3]

Former four term Los Angeles 8th District Councilman Robert Farrell, though retired, continues in conversations and activities to support and encourage social and economic justice as a board member of Liberty Community Empowerment/Downtown Crenshaw Rising, the Black Community Clergy Labor Alliance steering committee, and the Rotary Club of San Pedro. Farrell was active in CORE, the Congress on Racial Equality, as a student at UCLA. He brought his commitment from participation in the Freedom Rides to community political and civic mobilizations which set the ground for the women and men who are our public elected officials today. His emphases at City Hall included intergovernmental relations, regional governance, transportation, planning and land use, neighborhood community development and federal grants oversight. In the community, they were neighborhood and block club organization, support of the Council of Community Clubs, and involvement of churches and faith leaders.

He worked with the University of Southern California and the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency in the development of 300 units of Section 8 housing in the district and other amenities, including the Billy G. Mills and Rolland Curtis facilities in the greater Normandie area. Later, he attended USC’s Minority Program in Real Estate Finance and Development, and helped organize the Community Financial Resources Center. He is an advisor to One Source Fiduciary Solutions.

While representing Los Angeles in the National League of Cities organization, he joined NBC-LEO (National Black Caucus Local Elected Officials), and remains supportive through the National Policy Alliance, the umbrella organization of national black elected officials entities in the United States. In addition, he led in founding the Democratic Municipal Officials conference of the Democratic National Committee, served as its first representative on the DNC executive committee. and representative at the 1984 and 1988 Democratic National Conventions. He is a member of the board of the national Americans for Democratic Action and its Southern California chapters.

Politics

Campaigns

Farrell's first involvement in political life was in the Johnson-Humphrey Presidential campaign of 1964, and in 1970 he was statewide black communities coordinator in John Tunney's U.S. Senate race. In 1971 he was deputy minority communities director on the national staff of George McGovern, who was seeking the Democratic presidential nomination. He next worked for Tom Bradley's mayoral campaigns.[1]

Elections

See also List of Los Angeles municipal election returns, 1975 and after.

Farrell was employed as deputy to 8th District City Councilman Billy G. Mills,[1] and when Mills was appointed as a Superior Court judge in 1974, Farrell was elected to succeed him. In that era (1975), the district "ran in a north-south line in South-Central Los Angeles, from Adams and Jefferson Blvds. on the north, to Normandie and Central Avenue on the west, 118th St. on the south, and Arlington and Van Ness on the west." It suffered "some of the worst crime, unemployment and housing problems in the city."[4]

Farrell served for seventeen years altogether, although he did face one recall election—in 1978—and was threatened with another ten years later.. Recall proponents criticized Farrell for "dirty streets and alleys" and a controversial remark he had made the previous year supposedly indicating disregard for the rights of senior citizens. He beat the 1978 recall threat by 9,263 votes to 5,165[5] The second recall attempt, in 1988, failed when not enough signatures were gathered to put the question on the ballot.[6]

Liberal

Farrell was noted as a liberal who believed in an "active, interventionist role for government." This, it was said, distinguished him from other African-American council members—"Gilbert Lindsay and occasionally David Cunningham"—who relied more on the private sector in solving problems.[5]

Crime

Farrell was insistent in pushing the Los Angeles Police Department to end what he considered racism in the department,[7] and he urged an investigation of the controversial "choke hold" used by the police. But he also waged what was called a "personal war on crime and violence," and he said that "there is more to an anti-crime fight than law enforcement." For example, he called for an honor farm where convicted youths could earn money to compensate their victims. He thought of a municipal lottery to finance an anti-crime unit, and he advocated closing Nickerson Gardens and other crime-ridden public housing projects.[8]

At one point, Farrell had to stand and apologize to members of the Southside Serial Killer police task force for questioning whether the "best and the brightest" had been assigned to tracking down the murderer of eighteen women in South Los Angeles between 1983 and 1985.[9]

Farrell wrote a proposal for a special property tax that would be levied on South Los Angeles residents to pay for additional police, but after public opposition developed, he changed his mind and said he would no longer work for it, Proposition 7 on the June 1987 ballot.[10][11]

South Africa

Farrell was a consistent critic of the Apartheid regime of South Africa in the 1980s, and he used his position to promote those who championed the freedom of Nelson Mandela.[12][13] Farrell also played a leading role for the city of Los Angeles to divest from South Africa,[14][15] and he pushed for the city to deny government contracts to corporations that had ongoing businesses in Apartheid South Africa.[16] Upon the passage of divestiture, Farrell said "This is one where all of us are just doing ourselves and our nation and our city proud." He was subsequently thanked by Archbishop Desmond Tutu for his efforts.[17] In 1986, Farrell accompanied Rev. Jesse Jackson and a delegation of international diplomats and elected officials on a trip to Africa to urge an end to Apartheid.[18]

Other

Fluoridation. Farrell was among the majority of the ten City Council members who in 1974 voted in favor of fluoridating the city's water supply. Five were opposed.

Housing. The councilman stressed the need to improve existing dwellings, rather than to build new housing. "What we can count on is what we can see and what we can touch," he said in 1979.

Middle East. On a visit to Israel in 1984, Farrell warned that the expulsion of a group of African-American immigrants known as the Black Hebrews, as threatened by an official, "would produce resentment in America's black communities and would damage Israel's standing in American public opinion."[19] Along with Compton Mayor Walter R. Tucker and three other U.S. mayors, he made a trip to Saudi Arabia in 1988, funded by the Association of Arab-American University Graduates. The trip was briefly controversial when it was erroneously reported that he had not filed the proper financial documents with the city concerning the visit.[20][21]

Development. Despite the opposition of residents who claimed the project would destroy a block of historic homes in North University Park, Farrell supported and in 1987 voted for a shopping center south of Adams Boulevard between Vermont and Menlo avenues.[22] He acknowledged that he had received "several thousand dollars" in political contributions from the developers "over the years" but denied that "defenseless homeowners" were being exploited.[23][24]

Accusations In December 1987 the now defunct Los Angeles Herald-Examiner published a series of stories that alleged Farrell improperly provided public benefits to a small social service agency controlled by his wife in an alleged attempt to satisfy his alimony obligations to her. The stories alleged that Farrell had arranged for his wife’s agency, the Improvement Association of the Eighth District (IAED), to receive a $250,000 gift of real estate from Security Pacific Bank. The bank donated the property (a branch office and an adjoining parking lot) to the IAED agency. Subsequently, Farrell opened a field office in the building to better serve his constituents. The city paid IAED $2000-a-month to rent the former bank building and $400-a-month for the parking lot. IAED allegedly sold the parking lot to a developer shortly after acquiring it from Security Pacific, and yet IAED continued to receive rent from the city for that property for 21 months after that sale. IAED reimbursed the city $8,400 for the rent it had improperly received from the parking lot deal. Farrell responded to the claims that he was involved in the allegations: "There's no scheme....It would be foolish, absolutely foolish, for me to do that." Frustrated by the controversy, Farrell joined by local African-American leaders, held a news conference on the First Street steps of City Hall where he stated the "attacks" on him were part of a wider, national effort by a white-dominated media to marginalize outspoken African-American leaders like himself. Despite the protest, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Ira Reiner opened a "review" of Farrell's conduct that eventually became a full investigation. “We make a determination about whether the law has been violated,′ District attorney spokeswoman Sandi Gibbons said. ′It is up to others to make moral judgments." In Feb. 1991, three years after the allegations first broke, Reiner's office dropped its investigation. The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner was not around to report or remark on the decision of Reiner's office to drop the investigation; the paper folded on Nov. 1, 1989.

State Assembly race

In 1990, he suffered an upset defeat when he lost to Marguerite Archie-Hudson in his bid to represent the 48th district of the California State Assembly. The seat was previously held by Maxine Waters.[25][26]

References

- Los Angeles Public Library reference file

- Glenn F. Bunting, "Gift to City Allegedly Detoured by Farrell," Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1987, page B-1

- Glenn> F. Bunting, "Gift to City Allegedly Detoured by Farrell," Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1987, page B-1

- Doug Shuit, "5 Council Incumbents Coasting," Los Angeles Times, March 23, 1975, page E-2

- Henry Weinstein, "Farrell Win Shows Incumbent's Power," Los Angeles Times, August 17, 1978, page F-5

- Ted Vollmer, "Drive to Recall Farrell Fails," Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1988, page C-1

- Kristina Lindgren, "LAPD Discipline Probe Urged," Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1980, page A-23

- Sid Bernstein, "Farrell's Drive on Crime Hits Snag," Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1981, page OC-A-18

- "Councilman Apologizes to LAPD for Remarks on Murder Inquiry," Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1986, page OC-A-6

- "Unfair Tax" (editorial), Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1987, page C-4

- Scott Harris, "Farrell Says Staff Shake-Up Is Not Related to Tax Plan," Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1987, page D-3

- https://lasentinel.net/transafrica-movement-had-many-partsthat-mobilized-to-free-nelson-mandela.html

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1984/12/05/unions-join-protests-of-apartheid/c0737abe-464a-4463-bdbf-ed0e756d2340/

- https://articles.latimes.com/2011/aug/22/opinion/la-oe-newton-column-robert-farrell-20110822

- https://articles.latimes.com/1989-03-01/local/me-545_1_exemptions

- https://articles.latimes.com/1986-08-02/news/mn-853_1_los-angeles-convention-center

- https://articles.latimes.com/1986-07-03/local/me-993_1_apartheid

- Stanford, Karin L. (January 1997). Beyond the Boundaries: Reverend Jesse Jackson in International Affairs. SUNY Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780791434451.

Robert Farrell Los Angeles Apartheid.

- Norman Kempster, "L.A. Official Warns Israel Not to Oust Black Hebrews," Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1984, page B-6

- Glenn Bunting, "Farrell Failed to Report Free 1986 Trip to Mideast," Los Angeles Times, January 7, 1988, page N-1

- Glenn Bunting, "Farrell Did File a Report on Mideast Trip, City Clerk Says," Los Angeles Times, January 8, 1988, page 1

- Location on Bing Maps

- Frank Clifford, "Farrell Seeks CRA Aid for Supporters' Shop Center Project," Los Angeles Times, January 8, 1987, page C-1

- Frank Clifford, "Farrell Supports Mall Despite Wave of Protest," Los Angeles Times, January 22, 1987, page A-6

- Gladstone, Mark (March 10, 1990). "Retirements Unleash a Scramble for Several Seats". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California.

- Morrison, Patt (May 30, 1992). "48th Assembly District: 4 Democrats Wrestle in Redrawn Area". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California.

| Preceded by Billy G. Mills |

Los Angeles City Council 8th District 1974–91 |

Succeeded by Mark Ridley-Thomas |