1964 United States presidential election

The 1964 United States presidential election was the 45th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 3, 1964. Incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee. With 61.1% of the popular vote, Johnson won the largest share of the popular vote of any candidate since the largely uncontested 1820 election.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 61.9%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

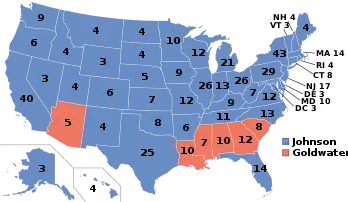

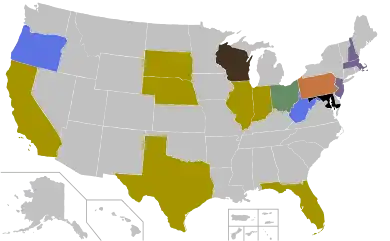

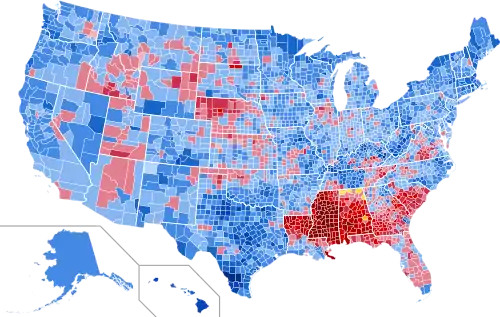

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Johnson/Humphrey and red denotes those won by Goldwater/Miller. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Johnson took office on November 22, 1963, following the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy. He easily defeated a primary challenge by segregationist Governor George Wallace of Alabama to win the nomination to a full term. At the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Johnson also won the nomination of his preferred running mate, United States Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. United States Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, a leader of his party's conservative faction, defeated moderate Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania at the 1964 Republican National Convention.

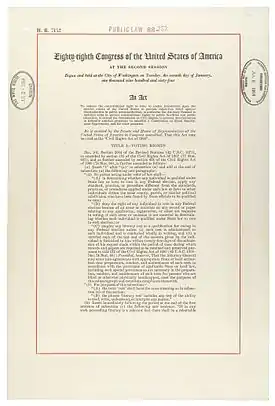

Johnson also championed his passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, also advocating a series of anti-poverty programs collectively known as the Great Society. Goldwater espoused a low-tax, small-government philosophy. Although he supported previous attempts to pass civil rights legislation in 1957 and 1960 as well as the 24th Amendment outlawing the poll tax, Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as he felt that Title II violated individual liberty and states' rights. Democrats successfully portrayed Goldwater as a dangerous extremist, most famously in the "Daisy" television advertisement. The Republicans were divided between its moderate and conservative factions, with Rockefeller and other moderate party leaders refusing to campaign for Goldwater. Johnson led by wide margins in all opinion polls conducted during the campaign, although his lead continued to dwindle throughout.

Johnson carried 44 states and the District of Columbia, which voted for the first time in this election. Goldwater won his home state and swept the states of the Deep South, most of which had not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since the end of Reconstruction in 1877. This was the last time that the Democratic Party won the white vote, although they came close in 1992. This was the first election since 1852 where the Democrats carried Maine, and the first ever and only election before 1992 where the Democrats carried Vermont. This was also the only election in which the Democrats carried Alaska. It was also the last time that Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska[lower-alpha 1], Kansas, and Oklahoma voted Democratic; as such, this was the most recent presidential election in which the entire Midwestern region voted Democratic. California and Illinois would not vote Democratic again until 1992, while Indiana and Virginia would not vote Democratic again until 2008.

Johnson's landslide victory coincided with the defeat of many conservative Republican Congressmen. The subsequent 89th Congress would pass major legislation such as the Social Security Amendments of 1965 and the Voting Rights Act. Goldwater's unsuccessful bid significantly influenced the modern conservative movement. The long-term realignment of conservatives to the Republican Party continued, culminating in the 1980 presidential victory of Ronald Reagan.

Assassination of President John F. Kennedy

While on the first stop of his 1964 reelection campaign, President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas. Supporters were shocked and saddened by the loss of the charismatic President, while opposition candidates were put in the awkward position of running against the policies of a slain political figure.[2]

During the following period of mourning, Republican leaders called for a political moratorium, so as not to appear disrespectful.[3][4] As such, little politicking was done by the candidates of either major party until January 1964, when the primary season officially began.[5] At the time, most political pundits saw Kennedy's assassination as leaving the nation politically unsettled.[2]

Nominations

Democratic Party

| 1964 Democratic Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyndon B. Johnson | Hubert Humphrey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36th President of the United States (1963–1969) |

U.S. Senator from Minnesota (1949–1964, 1971–1978) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates

President Lyndon B. Johnson

President Lyndon B. Johnson Governor Pat Brown of California

Governor Pat Brown of California Governor George Wallace of Alabama

Governor George Wallace of Alabama Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty of California

Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty of California

The only candidate other than President Johnson to actively campaign was then Alabama Governor George Wallace who ran in a number of northern primaries, though his candidacy was more to promote the philosophy of states' rights among a northern audience; while expecting some support from delegations in the South, Wallace was certain that he was not in contention for the Democratic nomination.[6] Johnson received 1,106,999 votes in the primaries.

At the national convention the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) claimed the seats for delegates for Mississippi, not on the grounds of Party rules, but because the official Mississippi delegation had been elected by a white primary system. The national party's liberal leaders supported an even division of the seats between the two Mississippi delegations; Johnson was concerned that, while the regular Democrats of Mississippi would probably vote for Goldwater anyway, rejecting them would lose him the South. Eventually, Hubert Humphrey, Walter Reuther and the black civil rights leaders including Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King Jr., and Bayard Rustin worked out a compromise: the MFDP took two seats; the regular Mississippi delegation was required to pledge to support the party ticket; and no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation chosen by a discriminatory poll. Joseph L. Rauh Jr., the MFDP's lawyer, initially refused this deal, but they eventually took their seats. Many white delegates from Mississippi and Alabama refused to sign any pledge, and left the convention; and many young civil rights workers were offended by any compromise.[7] Johnson biographers Rowland Evans and Robert Novak claim that the MFDP fell under the influence of "black radicals" and rejected their seats.[8] Johnson lost Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina.

Johnson also faced trouble from Robert F. Kennedy, President Kennedy's younger brother and the U.S. Attorney General. Kennedy and Johnson's relationship was troubled from the time Robert Kennedy was a Senate staffer. Then-Majority Leader Johnson surmised that Kennedy's hostility was the direct result of the fact that Johnson frequently recounted a story that embarrassed Kennedy's father, Joseph P. Kennedy, the ambassador to the United Kingdom. According to his recounting, Johnson and President Franklin D. Roosevelt misled the ambassador, upon a return visit to the United States, to believe that Roosevelt wished to meet in Washington for friendly purposes; in fact Roosevelt planned to—and did—fire the ambassador, due to the ambassador's well publicized views.[9] The Johnson–Kennedy hostility was rendered mutual in the 1960 primaries and the 1960 Democratic National Convention, when Robert Kennedy had tried to prevent Johnson from becoming his brother's running mate, a move that deeply embittered both men.

In early 1964, despite his personal animosity for the president, Kennedy had tried to force Johnson to accept him as his running mate. Johnson eliminated this threat by announcing that none of his cabinet members would be considered for second place on the Democratic ticket. Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use his scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to make him Johnson's running mate; he prevented this by deliberately scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, after his running mate had already been chosen. Shortly after the 1964 Democratic Convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in New York; he won the general election in November. Johnson chose United States Senator Hubert Humphrey from Minnesota, a liberal and civil rights activist, as his running mate.

Republican Party

| 1964 Republican Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Barry Goldwater | William E. Miller | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) |

U.S. Representative from New York (1951–1965) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates

Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona

Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona Senator Hiram Fong from Hawaii

Senator Hiram Fong from Hawaii Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania

Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania Senator Margaret Chase Smith from Maine

Senator Margaret Chase Smith from Maine Representative John W. Byrnes from Wisconsin

Representative John W. Byrnes from Wisconsin U.N. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. from Massachusetts

U.N. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. from Massachusetts Governor James A. Rhodes of Ohio

Governor James A. Rhodes of Ohio Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York

Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York Former Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota

Former Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota

The primaries

The Republican Party (GOP) was badly divided in 1964 between its conservative and moderate-liberal factions. Former Vice-President Richard Nixon, who had been beaten by Kennedy in the extremely close 1960 presidential election, decided not to run. Nixon, a moderate with ties to both wings of the GOP, had been able to unite the factions in 1960; in his absence the way was clear for the two factions to engage in an all-out political civil war for the nomination. Barry Goldwater, a Senator from Arizona, was the champion of the conservatives. The conservatives had historically been based in the American Midwest, but beginning in the 1950s they had been gaining in power in the South and West. The conservatives favored a low-tax, small federal government which supported individual rights and business interests and opposed social welfare programs. The conservatives also resented the dominance of the GOP's moderate wing, which was based in the Northeastern United States. Since 1940, the Eastern moderates had defeated conservative presidential candidates at the GOP's national conventions. The conservatives believed the Eastern moderates were little different from liberal Democrats in their philosophy and approach to government. Goldwater's chief opponent for the Republican nomination was Nelson Rockefeller, the Governor of New York and the longtime leader of the GOP's liberal-moderate faction.

Initially, Rockefeller was considered the front-runner, ahead of Goldwater. However, in 1963, two years after Rockefeller's divorce from his first wife, he married Margaretta "Happy" Murphy, who was nearly 18 years younger than he and had just divorced her husband and surrendered her four children to his custody.[10] The fact that Murphy had suddenly divorced her husband before marrying Rockefeller led to rumors that Rockefeller had been having an extramarital affair with her. This angered many social conservatives and female voters within the GOP, many of whom called Rockefeller a "wife stealer".[10] After his remarriage, Rockefeller's lead among Republicans lost 20 points overnight.[10] Senator Prescott Bush of Connecticut, the father of President George H. W. Bush and grandfather of President George W. Bush, was among Rockefeller's critics on this issue: "Have we come to the point in our life as a nation where the governor of a great state—one who perhaps aspires to the nomination for president of the United States—can desert a good wife, mother of his grown children, divorce her, then persuade a young mother of four youngsters to abandon her husband and their four children and marry the governor?"[10]

In the first primary, in New Hampshire, both Rockefeller and Goldwater were considered to be the favorites, but the voters instead gave a surprising victory to the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Nixon's running mate in 1960 and a former Massachusetts senator. Lodge was a write-in candidate. He went on to win the Massachusetts and New Jersey primaries before withdrawing his candidacy because he had finally decided he did not want the Republican nomination.[11]

Despite his defeat in New Hampshire, Goldwater pressed on, winning the Illinois, Texas, and Indiana primaries with little opposition, and Nebraska's primary after a stiff challenge from a draft-Nixon movement. Goldwater also won a number of state caucuses and gathered even more delegates. Meanwhile, Nelson Rockefeller won the West Virginia and Oregon primaries against Goldwater, and William Scranton won in his home state of Pennsylvania. Both Rockefeller and Scranton also won several state caucuses, mostly in the Northeast.

The final showdown between Goldwater and Rockefeller was in the California primary. In spite of the previous accusations regarding his marriage, Rockefeller led Goldwater in most opinion polls in California, and he appeared headed for victory when his new wife gave birth to a son, Nelson Rockefeller Jr., three days before the primary.[10] His son's birth brought the issue of adultery front and center, and Rockefeller suddenly lost ground in the polls.[10] Goldwater won the primary by a narrow 51–49% margin, thus eliminating Rockefeller as a serious contender and all but clinching the nomination. With Rockefeller's elimination, the party's moderates and liberals turned to William Scranton, the Governor of Pennsylvania, in the hopes that he could stop Goldwater. However, as the Republican Convention began Goldwater was seen as the heavy favorite to win the nomination. This was notable, as it signified a shift to a more conservative-leaning Republican Party.

Total popular vote

- Barry Goldwater – 2,267,079 (38.33%)

- Nelson A. Rockefeller – 1,304,204 (22.05%)

- James A. Rhodes – 615,754 (10.41%)

- Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. – 386,661 (6.54%)

- John W. Byrnes – 299,612 (5.07%)

- William W. Scranton – 245,401 (4.15%)

- Margaret Chase Smith – 227,007 (3.84%)

- Richard Nixon – 197,212 (3.33%)

- Unpledged – 173,652 (2.94%)

- Harold Stassen – 114,083 (1.93%)

- Other – 58,933 (0.99%)

- Lyndon Johnson (write-in) – 23,406 (0.40%)

- George Romney – 1,955 (0.03%)

Convention

The 1964 Republican National Convention at Daly City, California's Cow Palace arena was one of the most bitter on record, as the party's moderates and conservatives openly expressed their contempt for each other. Rockefeller was loudly booed when he came to the podium for his speech; in his speech he roundly criticized the party's conservatives, which led many conservatives in the galleries to yell and scream at him. A group of moderates tried to rally behind Scranton to stop Goldwater, but Goldwater's forces easily brushed his challenge aside, and Goldwater was nominated on the first ballot. The presidential tally was as follows:

- Barry Goldwater 883

- William Scranton 214

- Nelson Rockefeller 114

- George Romney 41

- Margaret Chase Smith 27

- Walter Judd 22

- Hiram Fong 5

- Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. 2

The vice-presidential nomination went to little-known Republican Party Chairman William E. Miller, a Representative from upstate New York. Goldwater stated that he chose Miller simply because "he drives [President] Johnson nuts". This would be the only Republican ticket between 1948 and 1976 that did not include Nixon.

In accepting his nomination, Goldwater uttered his most famous phrase (a quote from Cicero suggested by speechwriter Harry Jaffa): "I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue."[12] For many GOP moderates, Goldwater's speech was seen as a deliberate insult, and many of these moderates would defect to the Democrats in the fall election.

General election

Campaign

Although Goldwater had been successful in rallying conservatives, he was unable to broaden his base of support for the general election. Shortly before the Republican Convention, he had alienated moderate Republicans by his vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[13] which Johnson championed and signed into law. Goldwater said that he considered desegregation a states' rights issue, rather than a national policy, and believed the 1964 act to be unconstitutional. Goldwater's vote against the legislation helped cause African-Americans to overwhelmingly support Johnson.[14] Goldwater had previously voted in favor of the 1957 and 1960 Civil Rights acts, but only after proposing "restrictive amendments" to them.[14] Goldwater was famous for speaking "off-the-cuff" at times, and many of his former statements were given wide publicity by the Democrats. In the early 1960s, Goldwater had called the Eisenhower administration "a dime store New Deal", and the former president never fully forgave him or offered him his full support in the election.

In December 1961, he told a news conference that "sometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea", a remark which indicated his dislike of the liberal economic and social policies that were often associated with that part of the nation. That comment came back to haunt him, in the form of a Johnson television commercial,[15] as did remarks about making Social Security voluntary[16] and selling the Tennessee Valley Authority. In his most famous verbal gaffe, Goldwater once joked that the U.S. military should "lob one [a nuclear bomb] into the men's room of the Kremlin" in the Soviet Union.

Goldwater was also hurt by the reluctance of many prominent moderate Republicans to support him. Governors Nelson Rockefeller of New York and George Romney of Michigan refused to endorse Goldwater and did not campaign for him. On the other hand, former Vice President Richard Nixon and Governor Scranton of Pennsylvania loyally supported the GOP ticket and campaigned for Goldwater, although Nixon did not entirely agree with Goldwater's political stances and said that it would "be a tragedy" if Goldwater's platform were not "challenged and repudiated" by the Republicans.[17] The New York Herald-Tribune, a voice for eastern Republicans (and a target for Goldwater activists during the primaries), supported Johnson in the general election. Some moderates even formed a "Republicans for Johnson" organization, although most prominent GOP politicians avoided being associated with it.

Shortly before the Republican convention, CBS reporter Daniel Schorr wrote from Germany that "It looks as though Senator Goldwater, if nominated, will be starting his campaign here in Bavaria, center of Germany's right wing." He noted that a prior Goldwater interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel was an "appeal to right-wing elements". However, there was no ulterior motive for the trip; it was just a vacation.[18]

Fact magazine published an article polling psychiatrists around the country as to Goldwater's sanity. Some 1,189 psychiatrists appeared to agree that Goldwater was "emotionally unstable" and unfit for office, though none of the members had actually interviewed him. The article received heavy publicity and resulted in a change to the ethics guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association. In a libel suit, a federal court awarded Goldwater $1 in compensatory damages and $75,000 in punitive damages.[19][20][21][22][23]

Eisenhower's strong backing could have been an asset to the Goldwater campaign, but instead, its absence was clearly noticed. When questioned about the presidential capabilities of the former president's younger brother, university administrator Milton S. Eisenhower, in July 1964, Goldwater replied, "One Eisenhower in a generation is enough." However, Eisenhower did not openly repudiate Goldwater and made one television commercial for Goldwater's campaign.[24] A prominent Hollywood celebrity who vigorously supported Goldwater was Ronald Reagan. Reagan gave a well-received televised speech supporting Goldwater; it was so popular that Goldwater's advisors had it played on local television stations around the nation. Many historians consider this speech—"A Time for Choosing"—to mark the beginning of Reagan's transformation from an actor to a political leader. In 1966, Reagan would be elected Governor of California in a landslide.

Ads and slogans

Johnson positioned himself as a moderate and succeeded in portraying Goldwater as an extremist. Goldwater had a habit of making blunt statements about war, nuclear weapons, and economics that could be turned against him. Most famously, the Johnson campaign broadcast a television commercial on September 7 dubbed the "Daisy Girl" ad, which featured a little girl picking petals from a daisy in a field, counting the petals, which then segues into a launch countdown and a nuclear explosion.[25] The ads were in response to Goldwater's advocacy of "tactical" nuclear weapons use in Vietnam.[26] "Confessions of a Republican", another Johnson ad, features a monologue from a man who tells viewers that he had previously voted for Eisenhower and Nixon, but now worries about the "men with strange ideas", "weird groups" and "the head of the Ku Klux Klan" who were supporting Goldwater; he concludes that "either they're not Republicans, or I'm not".[27] Voters increasingly viewed Goldwater as a right-wing fringe candidate. His slogan "In your heart, you know he's right" was successfully parodied by the Johnson campaign into "In your guts, you know he's nuts", or "In your heart, you know he might" (as in "he might push the nuclear button"), or even "In your heart, he's too far right".[28][29]

The Johnson campaign's greatest concern may have been voter complacency leading to low turnout in key states. To counter this, all of Johnson's broadcast ads concluded with the line: "Vote for President Johnson on November 3. The stakes are too high for you to stay home." The Democratic campaign used two other slogans, "All the way with LBJ"[30] and "LBJ for the USA".[31]

The election campaign was disrupted for a week by the death of former president Herbert Hoover on October 20, 1964, because it was considered disrespectful to be campaigning during a time of mourning. Hoover died of natural causes. He had been U.S. president from 1929 to 1933. Both major candidates attended his funeral.[32]

Johnson led in all opinion polls by huge margins throughout the entire campaign.[33]

Results

The election was held on November 3, 1964. Johnson beat Goldwater in the general election, winning over 61% of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the popular vote first became widespread in 1824. In the end, Goldwater won only his native state of Arizona and five Deep South states—Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina—which had been increasingly alienated by Democratic civil rights policies.

The five Southern states that voted for Goldwater swung over dramatically to support him. For instance, in Mississippi, where Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt had won 97% of the popular vote in 1936, Goldwater won 87% of the vote.[34] Of these states, Louisiana had been the only state where a Republican had won even once since Reconstruction. Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina had not voted Republican in any presidential election since Reconstruction, whilst Georgia had never voted Republican even during Reconstruction (thus making Goldwater the first Republican to ever carry Georgia).

The 1964 election was a major transition point for the South, and an important step in the process by which the Democrats' former "Solid South" became a Republican bastion. Nonetheless, Johnson still managed to eke out a bare popular majority of 51–49% (6.307 to 5.993 million) in the eleven former Confederate states. Conversely, Johnson was the first Democrat ever to carry the state of Vermont in a Presidential election, and only the second Democrat, after Woodrow Wilson in 1912 when the Republican Party was divided, to carry Maine in the twentieth century. Maine and Vermont had been the only states that FDR had failed to carry during any of his four successful presidential bids.

Of the 3,126 counties/districts/independent cities making returns, Johnson won in 2,275 (72.77%) while Goldwater carried 826 (26.42%). Unpledged Electors carried six counties in Alabama (0.19%).

The Johnson landslide defeated many conservative Republican congressmen, giving him a majority that could overcome the conservative coalition.

This is the first election to have participation of the District of Columbia under the 23rd Amendment to the US Constitution.

The Johnson campaign broke two American election records previously held by Franklin Roosevelt: the most number of Electoral College votes won by a major-party candidate running for the White House for the first time (with 486 to the 472 won by Roosevelt in 1932) and the largest share of the popular vote under the current Democratic/Republican competition (Roosevelt won 60.8% nationwide, Johnson 61.1%). This first-time electoral count was exceeded when Ronald Reagan won 489 votes in 1980. Johnson retains the highest percentage of the popular vote as of the 2020 presidential election.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Lyndon Baines Johnson (Incumbent) | Democratic | Texas | 43,127,041 | 61.05% | 486 | Hubert Horatio Humphrey | Minnesota | 486 |

| Barry Morris Goldwater | Republican | Arizona | 27,175,754 | 38.47% | 52 | William Edward Miller | New York | 52 |

| (Unpledged Electors) | Democratic | Alabama | 210,732 | 0.30% | 0 | Alabama | 0 | |

| Eric Hass | Socialist Labor | New York | 45,189 | 0.06% | 0 | Henning A. Blomen | Massachusetts | 0 |

| Clifton DeBerry | Socialist Workers | Illinois | 32,706 | 0.05% | 0 | Ed Shaw | Michigan | 0 |

| Earle Harold Munn | Prohibition | Michigan | 23,267 | 0.03% | 0 | Mark R. Shaw | Massachusetts | 0 |

| John Kasper | States' Rights | New York | 6,953 | 0.01% | 0 | J. B. Stoner | Georgia | 0 |

| Joseph B. Lightburn | Constitution | West Virginia | 5,061 | 0.01% | 0 | Theodore Billings | Colorado | 0 |

| Other | 12,581 | 0.02% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 70,639,284 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

Source (popular vote): Leip, David. "1964 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

Source (electoral vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

Geography of results

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Presidential election results by county

Presidential election results by county Democratic presidential election results by county

Democratic presidential election results by county Republican presidential election results by county

Republican presidential election results by county Unpledged Electors presidential election results by county

Unpledged Electors presidential election results by county "Other" presidential election results by county

"Other" presidential election results by county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county Cartogram of Unpledged Electors presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Unpledged Electors presidential election results by county Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

| States/districts won by Johnson/Humphrey |

| States/districts won by Goldwater/Miller |

| Lyndon B. Johnson Democratic |

Barry Goldwater Republican |

Unpledged Electors Unpledged Democratic |

Eric Hass Socialist Labor |

Margin | State total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 10 | - | - | - | 479,085 | 69.45 | 10 | 210,732 | 30.55 | - | - | - | - | −268,353 | −38.90 | 689,817 | AL |

| Alaska | 3 | 44,329 | 65.91 | 3 | 22,930 | 34.09 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21,399 | 31.82 | 67,259 | AK |

| Arizona | 5 | 237,753 | 49.45 | - | 242,535 | 50.45 | 5 | - | - | - | 482 | 0.10 | - | −4,782 | −1.00 | 480,770 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 6 | 314,197 | 56.06 | 6 | 243,264 | 43.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70,933 | 12.66 | 560,426 | AR |

| California | 40 | 4,171,877 | 59.11 | 40 | 2,879,108 | 40.79 | - | - | - | - | 489 | 0.01 | - | 1,292,769 | 18.32 | 7,057,586 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 476,024 | 61.27 | 6 | 296,767 | 38.19 | - | - | - | - | 302 | 0.04 | - | 179,257 | 23.07 | 776,986 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 826,269 | 67.81 | 8 | 390,996 | 32.09 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 435,273 | 35.72 | 1,218,578 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 122,704 | 60.95 | 3 | 78,078 | 38.78 | - | - | - | - | 113 | 0.06 | - | 44,626 | 22.17 | 201,320 | DE |

| D.C. | 3 | 169,796 | 85.50 | 3 | 28,801 | 14.50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 140,995 | 71.00 | 198,597 | DC |

| Florida | 14 | 948,540 | 51.15 | 14 | 905,941 | 48.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 42,599 | 2.30 | 1,854,481 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 522,557 | 45.87 | - | 616,584 | 54.12 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | −94,027 | −8.25 | 1,139,336 | GA |

| Hawaii | 4 | 163,249 | 78.76 | 4 | 44,022 | 21.24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 119,227 | 57.52 | 207,271 | HI |

| Idaho | 4 | 148,920 | 50.92 | 4 | 143,557 | 49.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5,363 | 1.83 | 292,477 | ID |

| Illinois | 26 | 2,796,833 | 59.47 | 26 | 1,905,946 | 40.53 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 890,887 | 18.94 | 4,702,841 | IL |

| Indiana | 13 | 1,170,848 | 55.98 | 13 | 911,118 | 43.56 | - | - | - | - | 1,374 | 0.07 | - | 259,730 | 12.42 | 2,091,606 | IN |

| Iowa | 9 | 733,030 | 61.88 | 9 | 449,148 | 37.92 | - | - | - | - | 182 | 0.02 | - | 283,882 | 23.97 | 1,184,539 | IA |

| Kansas | 7 | 464,028 | 54.09 | 7 | 386,579 | 45.06 | - | - | - | - | 1,901 | 0.22 | - | 77,449 | 9.03 | 857,901 | KS |

| Kentucky | 9 | 669,659 | 64.01 | 9 | 372,977 | 35.65 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 296,682 | 28.36 | 1,046,105 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 387,068 | 43.19 | - | 509,225 | 56.81 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | −122,157 | −13.63 | 896,293 | LA |

| Maine | 4 | 262,264 | 68.84 | 4 | 118,701 | 31.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 143,563 | 37.68 | 380,965 | ME |

| Maryland | 10 | 730,912 | 65.47 | 10 | 385,495 | 34.53 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.00 | - | 345,417 | 30.94 | 1,116,457 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 1,786,422 | 76.19 | 14 | 549,727 | 23.44 | - | - | - | - | 4,755 | 0.20 | - | 1,236,695 | 52.74 | 2,344,798 | MA |

| Michigan | 21 | 2,136,615 | 66.70 | 21 | 1,060,152 | 33.10 | - | - | - | - | 1,704 | 0.05 | - | 1,076,463 | 33.61 | 3,203,102 | MI |

| Minnesota | 10 | 991,117 | 63.76 | 10 | 559,624 | 36.00 | - | - | - | - | 2,544 | 0.16 | - | 431,493 | 27.76 | 1,554,462 | MN |

| Mississippi | 7 | 52,618 | 12.86 | - | 356,528 | 87.14 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | −303,910 | −74.28 | 409,146 | MS |

| Missouri | 12 | 1,164,344 | 64.05 | 12 | 653,535 | 35.95 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 510,809 | 28.10 | 1,817,879 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 164,246 | 58.95 | 4 | 113,032 | 40.57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 51,214 | 18.38 | 278,628 | MT |

| Nebraska | 5 | 307,307 | 52.61 | 5 | 276,847 | 47.39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30,460 | 5.22 | 584,154 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 79,339 | 58.58 | 3 | 56,094 | 41.42 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 23,245 | 17.16 | 135,433 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 184,064 | 63.89 | 4 | 104,029 | 36.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 78,036 | 27.78 | 286,094 | NH |

| New Jersey | 17 | 1,867,671 | 65.61 | 17 | 963,843 | 33.86 | - | - | - | - | 7,075 | 0.25 | - | 903,828 | 31.75 | 2,846,770 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 4 | 194,017 | 59.22 | 4 | 131,838 | 40.24 | - | - | - | - | 1,217 | 0.37 | - | 62,179 | 18.98 | 327,615 | NM |

| New York | 43 | 4,913,156 | 68.56 | 43 | 2,243,559 | 31.31 | - | - | - | - | 6,085 | 0.08 | - | 2,669,597 | 37.25 | 7,166,015 | NY |

| North Carolina | 13 | 800,139 | 56.15 | 13 | 624,844 | 43.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 175,295 | 12.30 | 1,424,983 | NC |

| North Dakota | 4 | 149,784 | 57.97 | 4 | 108,207 | 41.88 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 41,577 | 16.09 | 258,389 | ND |

| Ohio | 26 | 2,498,331 | 62.94 | 26 | 1,470,865 | 37.06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1,027,466 | 25.89 | 3,969,196 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 519,834 | 55.75 | 8 | 412,665 | 44.25 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 107,169 | 11.49 | 932,499 | OK |

| Oregon | 6 | 501,017 | 63.72 | 6 | 282,779 | 35.96 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 218,238 | 27.75 | 786,305 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 29 | 3,130,954 | 64.92 | 29 | 1,673,657 | 34.70 | - | - | - | - | 5,092 | 0.11 | - | 1,457,297 | 30.22 | 4,822,690 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 315,463 | 80.87 | 4 | 74,615 | 19.13 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0.00 | - | 240,848 | 61.74 | 390,091 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 215,700 | 41.10 | - | 309,048 | 58.89 | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | −93,348 | −17.79 | 524,756 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 163,010 | 55.61 | 4 | 130,108 | 44.39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32,902 | 11.22 | 293,118 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 634,947 | 55.50 | 11 | 508,965 | 44.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 125,982 | 11.01 | 1,143,946 | TN |

| Texas | 25 | 1,663,185 | 63.32 | 25 | 958,566 | 36.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 704,619 | 26.82 | 2,626,811 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 219,628 | 54.86 | 4 | 180,682 | 45.14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 38,946 | 9.73 | 400,310 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 108,127 | 66.30 | 3 | 54,942 | 33.69 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 53,185 | 32.61 | 163,089 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 558,038 | 53.54 | 12 | 481,334 | 46.18 | - | - | - | - | 2,895 | 0.28 | - | 76,704 | 7.36 | 1,042,267 | VA |

| Washington | 9 | 779,881 | 61.97 | 9 | 470,366 | 37.37 | - | - | - | - | 7,772 | 0.62 | - | 309,515 | 24.59 | 1,258,556 | WA |

| West Virginia | 7 | 538,087 | 67.94 | 7 | 253,953 | 32.06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 284,134 | 35.87 | 792,040 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 1,050,424 | 62.09 | 12 | 638,495 | 37.74 | - | - | - | - | 1,204 | 0.07 | - | 411,929 | 24.35 | 1,691,815 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 80,718 | 56.56 | 3 | 61,998 | 43.44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18,720 | 13.12 | 142,716 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 538 | 43,127,041 | 61.05 | 486 | 27,175,754 | 38.47 | 52 | 210,732 | 0.30 | - | 45,189 | 0.06 | - | 15,951,287 | 22.58 | 70,639,284 | US |

Voter demographics

| The 1964 presidential vote by demographic subgroup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic subgroup | Johnson | Goldwater | ||||

| Total vote | 61 | 38 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 60 | 40 | ||||

| Women | 62 | 38 | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 years old | 64 | 36 | ||||

| 30–49 years old | 61 | 39 | ||||

| 50 and older | 59 | 41 | ||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 59 | 41 | ||||

| Black | 94 | 6 | ||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Protestants | 55 | 45 | ||||

| Catholics | 76 | 24 | ||||

| Party | ||||||

| Democrats | 86 | 13 | ||||

| Republicans | 20 | 80 | ||||

| Independents | 56 | 44 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 66 | 34 | ||||

| High school | 62 | 38 | ||||

| College graduate or higher | 52 | 48 | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Professional and business | 54 | 46 | ||||

| White-collar | 57 | 43 | ||||

| Blue-collar | 71 | 29 | ||||

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 68 | 32 | ||||

| Midwest | 61 | 39 | ||||

| South | 51 | 48 | ||||

| West | 60 | 40 | ||||

| Union households | ||||||

| Union | 73 | 27 | ||||

Source: [36]

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (23 electoral votes):

- Arizona, 1.00%

- Idaho, 1.83%

- Florida, 2.30%

Margin of victory over 5%, but less than 10% (40 electoral votes):

- Nebraska, 5.22%

- Virginia, 7.36%

- Georgia, 8.25%

- Kansas, 9.03%

- Utah, 9.73%

Tipping point:

- Washington, 24.59%

Statistics

Counties with highest percent of vote (Democratic)

- Duval County, Texas 92.55%

- Knott County, Kentucky 90.61%

- Webb County, Texas 90.08%

- Jim Hogg County, Texas 89.87%

- Menominee County, Wisconsin 89.12%

Counties with highest percent of vote (Republican)

- Holmes County, Mississippi 96.59%

- Noxubee County, Mississippi 96.59%

- Amite County, Mississippi 96.38%

- Leake County, Mississippi 96.23%

- Franklin County, Mississippi 96.05%

Counties with highest percent of vote (other)

- Macon County, Alabama 61.54%

- Limestone County, Alabama 56.01%

- Jackson County, Alabama 53.53%

- Lauderdale County, Alabama 52.45%

- Colbert County, Alabama 51.41%

Consequences

Although Goldwater was decisively defeated, some political pundits and historians believe he laid the foundation for the conservative revolution to follow. Among them is Richard Perlstein, historian of the American conservative movement, who wrote of Goldwater's defeat, "Here was one time, at least, when history was written by the losers."[38] Ronald Reagan's speech on Goldwater's behalf, grassroots organization, and the conservative takeover (although temporary in the 1960s) of the Republican party would all help to bring about the "Reagan Revolution" of the 1980s.

Johnson went from his victory in the 1964 election to launch the Great Society program at home, signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and starting the War on Poverty. He also escalated the Vietnam War, which eroded his popularity. By 1968, Johnson's popularity had declined and the Democrats became so split over his candidacy that he withdrew as a candidate. Moreover, his support of civil rights for blacks helped split white union members and Southerners away from Franklin Roosevelt's Democratic New Deal Coalition, which would later lead to the phenomenon of the "Reagan Democrat". Of the 14 presidential elections that followed up to 2020, Democrats would win only six times, although in 8 of those elections, a majority, the Democratic candidate received the highest number of popular votes.

The election also furthered the shift of the black voting electorate away from the Republican Party, a phenomenon which had begun with the New Deal. Since the 1964 election, Democratic presidential candidates have almost consistently won at least 80–90% of the black vote in each presidential election.

See also

- Conservatism in the United States

- History of the United States (1964–1980)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- Second inauguration of Lyndon B. Johnson

- 1964 United States gubernatorial elections

- 1964 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1964 United States Senate elections

- Natural born citizen of the United States (regarding Goldwater's Constitutional eligibility to be President)

- Scientists and Engineers for Johnson–Humphrey

Notes

- In 2008 and 2020, Barack Obama and Joe Biden each won an electoral vote from Nebraska's 2nd Congressional District.

References

- "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- Weaver Jr., Warren (November 23, 1963). "Parties' Outlook for '64 Confused". The New York Times. p. 1.

- Bigart, Homer (November 26, 1963). "GOP Leaders Ask Halt in Campaign". New York Times. p. 11.

- White 1965, pp. 59–60

- White 1965, p. 101

- "Jan 11, 1964: WALLACE CONSIDERS PRIMARIES IN NORTH". New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- Unger and Unger; LBJ; a Life (1999) pp. 325–26; Dallek Flawed Giant, p. 164

- Evans and Novak (1966) pp. 451–56

- Robert A. Caro; "The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power" (2012), ch. 3 ("It's about Roosevelt and his father", Johnson said)

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York: Basic Books. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- Johnson, Robert David, All the Way with LBJ, p. 111. ISBN 9780521425957

- "News Analysis; The Extremism Issue; Aides Say Goldwater Sought to Extol Patriotism and Defend His Party Stand". The New York Times. July 23, 1964. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "Civil Rights Act of 1964 – CRA – Title VII – Equal Employment Opportunities – 42 US Code Chapter 21". Archived from the original on January 25, 2010.

- Barnes, Bart (May 30, 1998). "Barry Goldwater, GOP Hero, Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "The Living Room Candidate – Commercials – 1964 – Eastern Seabord".

- "The Living Room Candidate – Commercials – 1964 – Social Security".

- Black, Conrad (2007), p. 464.

- Perlstein, Rick (2009). Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Nation Books. p. 375. ISBN 978-1568584126.

- Nick Gillespie (July 30, 2006). "The Hard Right". New York Times.

- Sally Satel (June 30, 2004). "Essay; The Perils of Putting National Leaders on the Couch". New York Times.

- "'64 Poll of Psychiatrists On Goldwater Defended". September 5, 1965.

- "EXPERT CONDEMNS GOLDWATER POLL – Tells Libel Trial Magazine Survey Was 'Loaded'". The New York Times. May 16, 1968.

- "Goldwater Awarded $75,000 in Damages In His Suit for Libel". The New York Times. May 25, 1968. p. 1.

- "The Living Room Candidate – Commercials – 1964 – Ike at Gettysburg".

- "The Living Room Candidate – Commercials – 1964 – Peace Little Girl (Daisy)".

- Farber, David. The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s. ISBN 1429931264

- "The Living Room Candidate – Commercials – 1964 – Confessions of a Republican".

- "10 worst political slogans of all time". The Daily Telegraph. March 23, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "Election and the Vietnam War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "Login to eResources, The University of Sydney Library". web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- "LBJ for the USA". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- Best, Gary Dean. Herbert Hoover, the Postpresidential Years, 1933–1964: 1946–1964. pp. 415, 431–32 ISBN 0817977511

- "Gallup Presidential Election Trial-Heat Trends, 1936–2008". Gallup, Inc.

- Kornacki, Steve (February 3, 2011). "The 'Southern Strategy', fulfilled". Salon.com. Archived April 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- "1964 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110726155334/http://www.gallup.com/poll/9454/Election-Polls-Vote-Groups-19601964.aspx

- "1964 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- Perlstein, Richard (2001). Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Nation Books. pp. x. ISBN 978-1-56858-412-6.

Further reading

- Davies, Gareth, and Julian E. Zelizer, eds. America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History (2015) pp. 184–195, role of liberalism.

- George H. Gallup, ed. (1972). The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935–1971. Random House.

- Steve Fraser; Gary Gerstle, eds. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930–1980.

- Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr., ed. (2001). History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2000.

- Barone, Michael; Grant Ujifusa (1967). The Almanac of American Politics 1966: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts.

- Brennan, Mary C. (1995). Turning Right in the Sixties: The Conservative Capture of the G.O.P. University of North Carolina Press.

- Burdick, Eugene (1964). The 480. – a political fiction novel around the Republican campaign.

- Dallek, Robert (2004). Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President.

- Donaldson, Gary (2003). Liberalism's Last Hurrah: The Presidential Campaign of 1964. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-1119-8.

- Evans, Rowland, and Novak, Robert (1966). Lyndon B. Johnson: The Exercise of Power.

- Farrington, Joshua D. (2020). "Evicted from the Party: Black Republicans and the 1964 Election". Journal of Arizona History 61.1: 127–148.

- Goldberg, Robert Alan (1995). Barry Goldwater.

- Hamby, Alonzo (1992). Liberalism and Its Challengers: From F.D.R. to Bush.

- Hodgson, Godfrey (1996). The World Turned Right Side Up: A History of the Conservative Ascendancy in America. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Jensen, Richard (1983). Grass Roots Politics: Parties, Issues, and Voters, 1854–1983.

- Jurdem, Laurence R. "'The Media Were Not Completely Fair to You': Foreign Policy, the Press and the 1964 Goldwater Campaign". Journal of Arizona History 61.1 (2020): 161–180.

- Kolkey, Jonathan Martin (1983). The New Right, 1960–1968: With Epilogue, 1969–1980.

- Ladd, Everett Carll Jr.; Charles D. Hadley (1978). Transformations of the American Party System: Political Coalitions from the New Deal to the 1970s (2nd ed.).

- Lesher, Stephan (1995). George Wallace.

- Mann, Robert (2011). Daisy Petals and Mushroom Clouds: LBJ, Barry Goldwater and the Ad That Changed American Politics. Louisiana State University Press.

- Matthews, Jeffrey J. (1997). "To Defeat a Maverick: The Goldwater Candidacy Revisited, 1963–1964". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 27 (4): 662.

- McGirr, Lisa (2002). Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right.

- Middendorf, J. William (2006). A Glorious Disaster: Barry Goldwater’s Presidential Campaign and the Origins of the Conservative Movement. Basic Books.

- Perlstein, Rick (2002). Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus.

- Rae, Nicol C. (1994). Southern Democrats. Oxford University Press.

- Sundquist, James L. (1983). Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States.

- White, Theodore (1965). The Making of the President: 1964.

Primary sources

- Gallup, George H., ed. (1972). The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935–1971. 3 vols. Random House.

- Chester, Edward W. (1977). A guide to political platforms.

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. (1973). National party platforms, 1840–1972.

External links

- United States presidential election of 1964 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Campaign commercials from the 1964 election

- CONELRAD's definitive history of the Daisy ad

- 1964 election results: State-by-state Popular vote

- 1964 popular vote by states (with bar graphs)

- 1964 popular vote by counties

- "How close was the 1964 election?", Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- electoral history

- Election of 1964 in Counting the Votes