Robert Fleming the elder

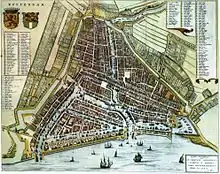

Robert Fleming the elder (1630 – 25 July 1694) was a Scottish Presbyterian Minister. Following the Restoration of King Charles II, he declined to accept the authority of the newly imposed bishops in the Kirk. He was therefore ejected as minister at Cambuslang. For the next ten years he remained in Scotland, preaching as he had opportunity. In 1669 he published the first part of Fulfilling of the Scripture in Rotterdam; it was later expanded to 3 parts and it is for this work and other treatises that Fleming is chiefly remembered.[3] On 3 September 1672 he declined indulgence at Kilwinning, disobeyed a citation of the Privy Council, and fled to London, where his Scottish speech somewhat marred his usefulness. On 30 December 1677 he was admitted colleague to John Hog, minister of the Scots Kirk, Rotterdam. After the Revolution he might have been restored to Cambuslang, but preferred to remain in Holland. While on a visit to London, he died of fever, 25 July 1694, after a short illness.[4] Daniel Burgess preached at his funeral and also recorded some memoirs of Fleming's life.[5]

Robert Fleming | |

|---|---|

| Born | Gifford |

| Died | 25 July 1694 London |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Dunbar (1650) |

| minister of Cambuslang | |

| In office 1653 – 1 October 1662[1] | |

| minister of Scots Kirk, Rotterdam | |

| In office 30 December 1677 – 25 July 1694[2] | |

Early life and education

.jpg.webp)

Robert Fleming was born in December 1630 at Yester, Haddingtonshire, of which parish, anciently known as St. Bathan's, his father, James Fleming (died 8 April 1653), was minister.[6] James Fleming's first wife was Martha, eldest daughter of John Knox, the Scottish reformer; Robert was the issue of a second marriage with Jean Livingston, a relative of John Livingstone. He had his early training at home.[4] His childhood was sickly, and he nearly lost his sight and life owing to a blow with a club. He speaks of an ‘extraordinary impression’ made upon him as a boy by a voice which he heard when he had climbed up into his father's pulpit at night; but he dates the beginning of his religious life from a communion day at Greyfriars Church, Edinburgh, at the opening of 1648.[6][7]At this time he was a student of Edinburgh University, where he, at fifteen had entered and from which he graduated M.A. on 26 July 1649, distinguishing himself in philosophy.[4] He pursued his theological studies at St. Andrews under Samuel Rutherford.[6] When he was only 20 he had joined the Covenanting army under David Leslie at The Battle of Dunbar (1650).

Cambuslang ministry

At the battle of Dunbar (3 September 1650) he was probably in the ranks of the Scottish army, for he speaks of his ‘signal preservation.’ After license he received a call to Cambuslang, Lanarkshire, and was ordained there in 1653. His health was then so bad that ‘it seemed hopeless’.[6]

Following the defeat and execution of King Charles I, and the conquest of Scotland, by the New Model Army of Oliver Cromwell, Fleming was called to be Minister of Cambuslang, when only 24. He remained there until the Restoration, when King Charles II re-established episcopacy in the Church of Scotland. Fleming's ministry was popular and successful. On the restoration of episcopacy the Scottish parliament passed an act (11 June 1662) vacating benefices that had been filled without respect to the rights of patrons, unless by 20 September the incumbent should obtain presentation (this patrons were enjoined to grant) and episcopal collation, and renounce the covenant. This is known as the Glasgow Act of 1662.[8] Failing to comply with these conditions, Fleming was deprived by the Privy Council of Scotland on 1 October. During the next ten years he remained in Scotland, preaching wherever he found opportunity. Indulgences were offered to the ejected ministers in 1669 by the king, and on 3 September 1672 by the privy council. By the terms of this latter indulgence Fleming was assigned to the parish of Kilwinning, Ayrshire, as a preacher. He disobeyed the order; when cited to the privy council on 4 September he did not attend, and a warrant was issued for his apprehension. He did not appear but was later apprehended and imprisoned in Edinburgh Tollbooth. He fled to London, where his broad Scottish ‘idiotisms and accents’ somewhat ‘clouded’ his usefulness. In 1674 he was again in Scotland, at West Nisbet, Roxburghshire, where he had left his wife. She died in that year, and Fleming returned to London.[6] From there he was called to become the Minister of the Scots Kirk in Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Rotterdam ministry

On 30 December 1677 he was admitted colleague [in succession to Robert MacWard] to John Hog [or Hoog], minister of the Scots Kirk, Rotterdam. Next year he visited Scotland for the purpose of bringing over his children. While there he held conventicles in Edinburgh, and was thrown into the Tolbooth. Brought before the privy council in June 1679, he agreed to give bail, but declined to promise a passive obedience. He was sent back to prison, but soon obtained his liberty and returned to Rotterdam. The Privy Council allowed him bail, June 1679, but refusing to conform to all its demands, he was sent back to confinement. On regaining his liberty, he returned to Rotterdam.

On 2 April 1683 proceedings were taken against him in the high court of judiciary at Edinburgh, on suspicion of harbouring some of the assassins of Archbishop Sharpe; his innocence appearing, the accusation was dropped on 17 April 1684. He did not formally demit the charge of Cambuslang till March 1688, on the death of David Cunningham, who had been appointed in his place. The act of April 1689 restored him to his benefice, but he preferred to remain in Holland. During a visit to London he was seized with fever on 17 July, and died on 25 July 1694.[4] Robertson seemed to erroneously think his death was in Cambuslang.[9]

Legacy

Daniel Burgess preached at his funeral and also recorded some memoirs of Fleming's life.[5] Fleming left a diary, which was not published; his rather confused list of thirty-eight memorable occurrences of his life, entitled A Short Index, &c., is printed at the end of Memoirs by Daniel Burgess, prefixed to the 1726 edition of the Fulfilling and in Howie's Scots Worthies.[10] A fuller memoir is prefixed to the 1845 edition.[11]

Wodrow characterises Fleming as a "devout and pious man, most spiritual in his carriage and writings, much engaged in secret prayer and meditations, very affectionate to his servants and people, full of love, and of a peaceable temper."[4]

Publications by Robert Fleming, Senior

Robert Fleming was renowned as a preacher and wrote a number of Calvinist theological books.

- Fulfilling of the Scripture, or An essay shewing the exact accomplishment of the Word of God in his works of providence, performed & to be performed. : For confirming the beleevers [sic], and convincing the atheists of the present time: containing in the… (1671)

- Faithfulness of God considered and cleared in the great events of his word, or, A second part of The fulfilling of the Scripture : where its convincing and near approach before mens eyes, with some clear discovery thereof in the work and conduct of providence… (1674)

- Scripture truth confirmed and cleared by some great appearances of God for his church under the New Testament : held forth with some special remarks thereon. From her first rise & planting amongst the nations, and that blessed recovery of late from Antichrist… (1678)

- Church wounded and rent by a spirit of division, held forth in a short account of some sad differences hath been of late in the Church of Scotland, with the occasion, grounds, and too evident product thereof whose wounds are bleeding to this day. (1681)

- Confirming worke of religion: in its necessity and use briefly held forth; that each Christian may have a proper ballast of his own, of the grounds and reasons of his faith… (1685)

- Confirming work of religion, or, Its great things made plain, by their primary evidences and demonstrations: whereby the meanest in the church may soon be made to render a solid and rational account of their faith (1693)

- Present aspect of our times, and of the extraordinary conjunction of things therein. : In a rational view and prospect of the same; as it respects the publick hazard and safety of Brittain in this day. Licensed November 29. 1693. (1694)

Fasti:[4]

- The Fulfilling of the Scripture (Rotterdam, 1669 ; 2nd ed., 1671)

- The Faithfulness of God, etc. [Second Part]

- The Great Appearances of God [Third Part]

- all three parts, 2 vols. (London, 1681 ; 3rd ed., 1681 ; 4th ed., 1693 ; 5th ed. [with Life and a Funeral Sermon by Daniel Burgess], 1726; latest edition [with Life by Thomas Thomson], Edinburgh, 1845)

- An Account of the Roman Church and Doctrine (London, 1675)

- A Survey of Quakerism [anon.] (1677)

- Scripture Truth confirmed and cleared (1678)

- The Truth and Certainty of the Protestant Faith (1678)

- The Church Wounded and Rent by a Spirit of Division (1681)

- The One Thing Necessary (1681)

- Joshua's Choice (1684) [originally printed in Dutch]

- The Confirming Worke of Religion (Rotterdam, 1685)

- True Statement of the Christian Faith (1692)

- Sermon on Ecclesiastes, vii., 1 (1692)

- Sermon on Jeremiah, xviii., 7-11 (1692)

- The Present Aspect of Our Times (London, 1694)

Family

He married

- Christian (died at West Nisbet in 1674), daughter of Sir George Hamilton of Binny, Linlithgowshire, and had issue —

- Robert, his successor at Rotterdam, born 1660, died 21 May 1716, and six others.[4]

Fleming's son Robert Fleming the younger succeeded him as Minister of the Scots Kirk in Rotterdam. He too became a noted Calvinist theologian, and was author of The Rise and Fall of the Papacy.

Bibliography

References

Citations

- Scott 1920, p. 236-237.

- Scott 1920, p. 237.

- Hewison 1913.

- Scott 1920.

- Burgess 1726.

- Gordon 1889.

- Howie 1870, p. 578.

- Fleming 1845, p. ix-xi.

- Robertson 1845, p. 429.

- Howie 1870.

- Fleming 1845.

- Steven 1832, p. 58-67.

Sources

- Anderson, William (1870). "Fleming, Robert". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. 2. A. Fullarton & co. pp. 221-222.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burgess, Daniel (1726). The Church's Triumph over Death: A Funeral- Sermon preached upon the Decease of Blessed Robert Fleming, late Pastor of a Church in Rotterdam; By Daniel Burgess. London: Printed for J. and B. Sprint. pp. i-xxiv.

- Chambers, Robert (1870). Thomson, Thomas (ed.). A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. New ed., rev. under the care of the publishers. With a supplementary volume, continuing the biographies to the present time. 2. Glasgow: Blackie. pp. 30-31.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleming, Robert (1845). The fulfilling of the Scripture (with biography of Fleming by the editor). 1. Edinburgh: Printed for the Assembly's Committee. pp. iii-xxviii.

- Gordon, Alexander (1889). "Fleming, Robert". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 19. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Grub, George (1861). An ecclesiastical history of Scotland : from the introduction of Christianity to the present time. 3. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 261–262.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hewison, James King (1913). The Covenanters. 2. Glasgow: John Smith and son. p. 547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howie, John (1870). "Robert Fleming". In Carslaw, W. H. (ed.). The Scots worthies. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson, & Ferrier. pp. 572-580.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Irving, Joseph (1881). The book of Scotsmen eminent for achievements in arms and arts, church and state, law, legislation, and literature, commerce, science, travel, and philanthropy. Paisley: A. Gardner. p. 144.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Johnston, John C. (1887). Treasury of the Scottish covenant. Andrew Elliot. p. 370-371.

- Kirkton, James (1817). Sharpe, C. K. (ed.). The secret and true history of the church of Scotland from the Restoration to the year 1678. Edinburgh: J. Ballantyne. pp. 480-481.

- Meek, James (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. 5. Edinburgh: Printed and sold by William Creech. pp. 241-274.

- Mullane, David George. "Fleming, Robert (1630–1694)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9710. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Porter, Wm Henry Cambuslang and its Ministers (in Mitchell Library - Glasgow Collection, reference GC941.433 CAM 188520 Box 952

- Robertson, John (1845). The new statistical account of Scotland. 6. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 416-442.

- Scott, Hew (1915). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. 1. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 399.

- Scott, Hew (1920). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. 3. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 236-237.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Steven, William (1832). The history of the Scottish church, Rotterdam. Edinburgh: Waugh & Innes, etc. pp. 83-113.

- Wilson, James Alexander OBE, MD A History of Cambuslang: a Clydesdale parish. Jackson Wylie & Co Glasgow (1929)

- Wodrow, Robert (1829). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation and notes, in four volumes. 3. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)