Robert Venables

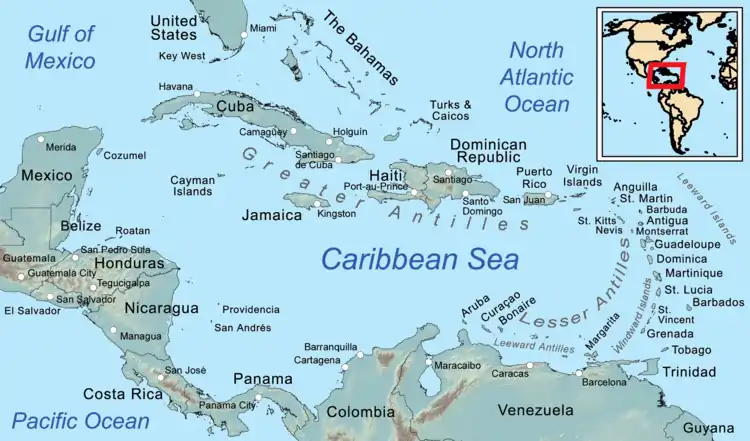

Robert Venables (ca. 1613–1687), was an English soldier from Cheshire, who fought for Parliament in the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and captured Jamaica in 1655.

Robert Venables | |

|---|---|

Map of Jamaica, captured by Venables during the 1655 Western Design | |

| Born | 1613 Antrobus, Cheshire |

| Died | 10 December 1687 (aged 73–74) Wincham, Cheshire |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1642–1655 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Jones' Regiment of Horse |

| Commands held | Governor of Tarvin Western Design 1654-1655 Governor of Chester, 1660 |

| Battles/wars | Wars of the Three Kingdoms Chester; Rowton Heath; Oxford; Cromwellian conquest of Ireland Rathmines Drogheda Lisnagarvey Scarrifholis Charlemont Anglo-Spanish War Santo Domingo Jamaica |

When the Anglo-Spanish War began in 1654, he was made joint commander of an expedition against Spanish possessions in the West Indies, known as the Western Design. Although he captured Jamaica, which remained a British colony for over 300 years, the project was considered a failure, ending his military career.

Appointed Governor of Chester shortly before The Restoration of Charles II in 1660, his religious views made him unacceptable to the new regime. He returned to private life and in 1662 published a treatise on fishing, The Experienced Angler, which went through five editions in his lifetime. Arrested but released without charge after the Farnley Wood Plot in 1663, in 1668 he purchased an estate at Wincham, Cheshire, where he lived quietly until his death in 1687.

Personal details

Robert Venables was the son of Robert Venables (ca 1579-1643) of Antrobus, Cheshire and Ellen Simcox (1577-1658), daughter of Richard Simcox of Rudheath; he seems to have had at least one sister, Elizabeth (1609-1683), but details are unclear. The Venables were a cadet branch of a family that could trace their ancestry back to the Norman Conquest, and were classed as members of the minor gentry.[1] His father had interests in the Cheshire salt mine industry and was part of a local Puritan network; Robert's godfather was the preacher Richard Mather, grandfather of Cotton Mather.[2]

His first wife was Elizabeth Rudyard; the date of their marriage is unknown, but appears to have been sometime in the mid 1630s, and she died before 1649. Only two of their five children survived into adulthood; Thomas (1640-1659), and Frances (1638-1692).[3]

Shortly before Venables went to Ireland in 1649, he became engaged to Elizabeth Lee (1614–1689), mother of seven and widow of Thomas Lee of Darnhall, Cheshire. They finally married on his return in 1654; at the same time, her son Thomas married his daughter Frances, while his son, also Thomas, married her daughter Elizabeth, breaking a prior engagement to another girl.[3] Their marriage was not a success; she allegedly 'disliked his politics, disdained his religion, and disapproved of his manners.'[1]

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Almost nothing is known of his career prior to the beginning of the First English Civil War in August 1642, when he raised a company for the Manchester garrison. In December, he was captured in a skirmish near Westhoughton, Lancashire but quickly released.[4] The Venables family had long-standing connections to the Breretons, one of the most powerful families in Cheshire, and for the rest of the war he served under Sir William Brereton, the senior local Parliamentarian. Despite lacking military experience, Brereton proved an energetic and resolute commander, winning minor victories in March 1643 at Middlewich and Hopton Heath.[5]

Brereton established his headquarters at Nantwich and quickly attained superiority over Arthur Capell, Royalist commander in Shropshire, Cheshire, and North Wales.[6] From August to September 1643, Venables was based at Cholmondeley, which he used as a base for attacking nearby Royalist garrisons. These supported the blockade of Chester, a town essential for funnelling men and material from Royalist areas in Ireland and North Wales. Their success led to Capell's replacement by Lord Byron in October 1643.[7]

Byron assembled an army of over 5,000, many of whom were veterans from the war in Ireland, and defeated the Parliamentarians at the Second Battle of Middlewich in December. Brereton appealed to Sir Thomas Fairfax for support, and their combined force routed the Royalists at Nantwich in January 1644. Having lost over 1,500 men and most of his artillery, Byron retreated into Chester, and Venables spent much of the next two years as governor of Tarvin.[8] When Chester finally surrendered in February 1646, Brereton recommended him as governor, but instead the position went to Irishman Michael Jones. Now a Lieutenant Colonel, Venables spent the next few months reducing Royalist garrisons in North Wales before the war ended in June.[1]

Despite victory, the cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague left Parliament unable to pay their soldiers. In summer 1647, the garrison of Nantwich mutinied; Venables restored order, and was made governor of Liverpool in January 1648, a position he held during the Second English Civil War.[1] Promoted colonel in 1649, he raised a regiment of Cheshire veterans sent to reinforce Michael Jones, newly appointed Parliamentarian Governor of Dublin. They arrived in time for the Battle of Rathmines on 2 August, a decisive victory over a Royalist/Confederate force under the Marquess of Ormond.[9]

On 15 August, Oliver Cromwell arrived with an expeditionary force of 12,000 to begin the conquest of Ireland, and Venables took part in the storming of Drogheda. Along with Michael Jones' brother Sir Theophilus, a detachment led by Venables joined forces with Sir Charles Coote in Ulster. Over the next twelve months, the three conducted a campaign to subdue the north, including the battles of Lisnagarvey and Scariffhollis. Charlemont, the last Confederate stronghold in Ulster, surrendered in August 1650, and their only significant field army dissolved in December when the Marquess of Clanricarde went into exile.[1]

Venables spent the next two years fighting an often brutal counter insurgency war in north Connaught and south-west Ulster; his troops were always in arrears with their pay, and on several occasions he and Jones resorted to confiscating taxes collected for Dublin.[10] In 1653, he helped implement the draconian 1652 Act of Settlement, while resisting attempts to impose Presbyterianism in Ulster; like many in the New Model, he was a religious Independent, who opposed any state-ordered church.[1]

The Western Design

Venables left Ireland in May 1654 and was appointed commander of land forces for the Western Design, an attack on the Spanish West Indies intended to secure a permanent base in the Caribbean. It was largely driven by Cromwell, who had been involved in the Providence Island Company, a Puritan colony established off the coast of Nicaragua in 1630 and abandoned in 1641.[11] Planning was based on input from Thomas Gage, a former missionary regarded as an expert on the region who claimed the Spanish colonies of Hispaniola and Cuba were weakly defended, advice which proved incorrect.[12]

Given the distances involved, Venables insisted on flexibility of objectives; Cromwell agreed and his instructions were simply "to gain an interest in that part of the West Indies in possession of the Spaniards". Leadership was shared with Admiral William Penn, who commanded the fleet, and two civilian commissioners, Edward Winslow, former Governor of Plymouth Colony, and Gregory Butler, who were to supervise colonisation of the captured lands. The fleet departed Portsmouth at the end of December 1654, with Venables accompanied by his new wife Elizabeth.[13]

Few veterans of the New Model were willing to serve in an area notorious for disease and on an expedition with such vague objectives, so many of the 2,500 troops brought from England were untrained, as well as poorly equipped.[14] They reached Barbados at the end of January and spent the next two months recruiting another 3,500 from indentured servants on the island and elsewhere in the region. The Spanish had been aware of the project for some time and this additional delay allowed them to send reinforcements to Hispaniola; the plan assumed secrecy and superior English forces, neither of which were true.[15]

The attack on Santo Domingo in April was disastrous; the troops raised in Barbados proved little more than a rabble, and after suffering nearly 1,000 casualties, mostly from disease or heatstroke, they were evacuated on 30 April. Despite opposition from Penn, Venables attacked Jamaica in late May; primarily a resupply point for Spanish ships, the main settlement of Santiago de la Vega was poorly defended and quickly surrendered, although resistance by Jamaican Maroons continued in the interior for several years.[16]

By this time the relationship between the two commanders had deteriorated completely, and on 25 June Penn sailed for England hoping to ensure his version of why the expedition failed was heard first. He was followed by Venables, who arrived on 9 September, emaciated and sick; Cromwell accused them both of desertion and threw them both in the Tower of London. Although soon released, they were both cashiered; Penn returned to the Royal Navy after the 1660 Restoration, but this ended Venables' military career.[1]

Later career

Cromwell died in September 1658 and was replaced as Protector by his son Richard, who was dismissed by the army in May 1659. Although sympathetic to restoring the monarchy, Venables avoided participation in Booth's Insurrection of August 1659, which was led by George Booth, a Presbyterian and colleague during the war in Cheshire. When George Monck took control of Parliament in February 1660, he appointed Venables governor of Chester but he was removed after The Restoration of Charles II, following pressure from local Royalists, ending his public career.[1]

In 1662, he published a treatise titled The Experienced Angler, with a preface by Izaak Walton, which went through five editions during his lifetime. A prominent supporter of local Nonconformists, he was accused of involvement in the 1663 Farnley Wood Plot, but released without charge. He sheltered the Covenanter dissident William Veitch after the Pentland Rising in 1666, and in 1683 was indicted as a supporter of the exiled Duke of Monmouth. He also served as a trustee of Sir John Deane's College, a school established in 1557 with a strong Puritan tradition; then in Chester, it moved to Northwich in 1905 and is now a Sixth form college.[17]

In 1668, he purchased an estate at Wincham where he died on 10 December 1687, leaving his property to his daughter Frances.[18]

References

- Morrill 2004.

- Cox & Hopkins 1975, p. 75.

- Townshend & Venables 1872, p. 7.

- Broxap 1910, p. 61.

- Morrill 2013.

- Hutton 2003, p. 62.

- Hutton 2003, pp. 125–126.

- Robinson 1895, p. 147.

- Hayes-McCoy 1990, p. 210.

- Dunlop 1913, pp. 245–246.

- Kupperman 2007.

- Plant "The Western Design".

- Harrington 2004, pp. 42–43.

- Harrington 2004, pp. 48–49.

- Harrington 2004, p. 55.

- Campbell 1988, pp. 14–17.

- Cox & Hopkins 1975, pp. 104–105.

- Lysons 1810, p. 534.

Sources

- Broxap, Ernest (1910). The Great Civil War in Lancashire. Manchester University Press.

- Campbell, Mavis (1988). The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: a History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal. Bergin & Garvey.

- Cox, Marjorie; Hopkins, LA (1975). A History of Sir John Deane's Grammar School, Northwich, 1557-1908. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719012822.

- Dunlop, Robert (1913). Ireland under the commonwealth; being a selection of documents relating to the government of Ireland from 1651 to 1659. Manchester University Press. OCLC 473591132.

- Harrington, Matthew Craig (2004). "The Worke Wee May Doe in the World": the Western Design and the Anglo-Spanish Struggle for the Caribbean, 1654–1655 (PDF) (PHD). Florida State University.

- Hayes-McCoy, Gerard Anthony (1990) [1969]. Irish Battles: A Military History of Ireland. Belfast: The Appletree Press. ISBN 0-86281-250-X.

- Hutton, Ronald (2003). The Royalist War Effort 1642–1646. Routledge. ISBN 9780415305402.

- Kupperman, Karen (2007). "Providence Island Company". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95346. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lysons, Daniel (1810). Magna Brittanica: Volume II The county palatine of Chester. Cadell & Davies.

- Morrill, John (2013). "Brereton, Sir William, first baronet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3333. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Morrill, John (2004). "Venables, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28181. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Plant, David. "The Western Design 1655". BCW Project. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Robinson, AM (1895). Cheshire in the Great Civil War (PDF). Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Townshend, Lee Porcher; Venables, Mrs. Elizabeth Aldersey Lee (1872). Some Account of General Robert Venables, of Antrobus and Wincham, Cheshire (with an Engraving from His Portrait at Wincham): Together with the Autobiographical Memoir, Or Diary, of His Widow, Elizabeth Venables. Chetham society.