Rocket U-boat

The Rocket U-boat was a series of military projects undertaken by Nazi Germany at the Peenemünde Army Research Center to develop submarine-launched rockets, flying bombs and missiles. The German Navy did not use submarine-launched rockets or missiles from U-boats against targets at sea or ashore. These projects never reached combat readiness before the war ended.

From 31 May to 5 June 1942, a series of underwater launching experiments of solid-fuel rockets were carried out using submarine U-511 as a launching platform. The rocket system was first envisaged as a weapon against convoy escorts, but with no effective guidance system, the arrangement was ineffective against moving targets and could only be used for shore bombardment. The development of this system ended in early 1943, as it was found to decrease the U-boats' seaworthiness.

Plans for the rocket U-boat involved an attack on New York City with newly invented V-2 rockets. Unmanned and unpowered, containers containing V-2 rockets were intended to be towed by a conventional U-boat to within the range of its target, then set up and launched from its gyro-stabilized platform. With thoughts to hit targets in the United States and in the United Kingdom, this suggestion progressed to the design of a 32-m long container of 500-tons displacement to be towed behind a submerged U-boat. The evacuation of Peenemünde in February 1945 brought an end to these developments. There are no records that these were tested with a rocket launch before Germany's final collapse. Although generously described as a forerunner of the ballistic missile submarines, the idea of launching V2-rockets from canisters towed by U-boats across the Atlantic Ocean embodied the mood of the desperation of Nazi Germany at the end of World War II.

After the war, the United States and the Soviet Union continued these projects with the assistance of captured German scientists. The US Navy fired reversed-engineered versions of the German V-1 flying bomb (Republic-Ford JB2 flying bombs) from submarines USS Cusk (SS-348) and USS Carbonero (SS-337) in a successful series of tests between 1947 and 1951. During Operation Sandy, a German V-2 rocket, seized by the US Army at the end of the war in Germany, was launched from the upper deck of the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CV-41) on 6 September 1947. Reportedly, in the Soviet Union, German scientists contributed to the development of GOLEM-1, a liquid-fueled rocket, based on the V-2 rocket design and designed to be launched from a capsule towed by a submarine.

Background

The British Area Bombing Directive issued on 14 February 1942 focused on undermining "the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular the industrial workers."[1][2] According to British philosopher A. C. Grayling, Lübeck, with its many timbered medieval buildings, was chosen because the RAF "Air Staff were eager to experiment with a bombing technique using a high proportion of incendiaries" to help them carry out the directive. The RAF was well aware that the technique of using a high proportion of incendiaries during bombing raids was effective because cities such as Coventry had been subject to such attacks by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz.[3] New heavy bombers, improved navigation and bombing systems, and new tactics led to a devastating increase in the effectiveness of the RAF's bombing offensive on Germany, starting with the bombing of Lübeck in March 1942. A series of follow-up attacks, taking much the same pattern, was mounted against Rostock between 24 and 27 April 1942.[4]

The destruction of Lübeck and Rostock came as a profound shock to the German leadership and population.[5][6] Hitler was enraged and ordered on 14 April 1942 "that the air war against England be given a more aggressive stamp. Accordingly, when targets are being selected, preference is to be given to those where attacks are likely to have the greatest possible effect on civilian life. Besides raids on ports and industry, terror attacks of a retaliatory nature [Vergeltungsangriffe] are to be carried out on towns other than London".[7] The Luftwaffe designed in April and May 1942 the Baedeker Raids on British cities with the hope of forcing the Royal Air Force to reduce their actions. The Luftwaffe continued to target cities for their cultural value for the next two years.[8] The Baedeker-type raids ended in 1944, as the Germans realized they were ineffective; unsustainable losses were being suffered for no material gain. January 1944 saw a switch to London as the principal target for retaliation. On 21 January the Luftwaffe mounted Operation Steinbock, an all-out attack on London employing all of its available bomber force in the west. This too was largely a failure and the efforts were re-directed toward the ports that the Germans suspected were going to be used for the allied invasion of Germany. Operation Steinbock was the last large-scale bombing campaign against England using conventional aircraft, and thenceforth only the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rockets – the pioneering examples of cruise missiles and short-range ballistic missiles respectively – were used to strike British cities.[9] The V-1 flying bomb, a pulsejet-powered cruise missile, and the V-2 rocket, a liquid-fueled ballistic missile were long-range "retaliatory weapons" (German:Vergeltungswaffen) specially designed for strategic bombing during World War II, particularly terror bombing and/or the aerial bombing of cities, as retaliation for the Allied bombings against German cities.[10][11]

Following the relative failure of the Baedeker Raids on Britain in May 1942, the development of both flying bombs and rockets accelerated, with Britain designated as the target.[12] The V-1 flying bomb was the first of the so-called "Vengeance weapons" series deployed for the terror bombing of London. It was developed at Peenemünde Army Research Center in 1939 by the Luftwaffe at the beginning of the Second World War. In July 1943, the V-1 flying bomb flew 245 kilometers and impacted within a kilometer of its target.[13][14] Ground-launched V-1s were propelled up a 49-m (160 ft)-long inclined launch ramp, consisting of 8 modular sections 6 m long and a muzzle brake, to enable the missile to become airborne with a strong enough air-flow allowing the pulse-jet engine to operate. The steam catapult accelerated the V-1 flying bomb to a launch speed of 200 mph, well above the needed minimum operational speed of 150 mph.[13] Its operational range was about 200 km (150 mi) and its maximum speed was about 640 km/h (400 mph).[13]

.svg.png.webp)

The V-2 rocket, with the technical name Aggregat 4 (A-4), was the world's first long-range guided ballistic missile developed by Wernher von Braun.[15] The first successful test flight of a V-2 rocket took place on 3 October 1942, reaching an altitude of 84.5 kilometres (52.5 miles).[16] The missile was powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine. The V-2 used a 75% ethanol/25% water mixture for fuel and liquid oxygen for oxidizer. The fuel and oxidizer pumps were driven by a steam turbine, and the steam was produced by concentrated hydrogen peroxide with sodium permanganate catalyst.[17]

At launch, the V-2 rocket propelled itself for up to 65 seconds, and a programmed motor held the inclination at the specified angle until engine shutdown, after which the rocket continued on a ballistic free-fall trajectory. The rocket reached a height of 80 km (50 mi) after shutting off the engine. Unlike the V-1, the V-2's speed and trajectory made it practically invulnerable to anti-aircraft guns and fighters, as it dropped from an altitude of 100–110 km (62–68 mi) at up to three times the speed of sound at sea level (approximately 3550 km/h).[14] Its operational range was about 320 km (200 mi).[16]

On 26 May 1943, Germany decided to put both the V-1 and the V-2 into production.[18] On 29 September 1943, Albert Speer publicly promised retribution against the mass bombing of German cities by a "secret weapon".[19] On 24 June 1944, the Reich Propaganda Ministry announcement of the "Vergeltungswaffe 1" guided missile implied that there would be another such weapon.[20]

Development

During World War II, several projects were undertaken by the German Navy at the Peenemünde Army Research Center to develop submarine-launched rockets, flying bombs and missiles.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27] These projects never reached combat readiness before the war ended. The German Navy did not use submarine-launched rockets or missiles from U-boats against targets at sea or ashore.

Short-range rockets

According to Walter Dornberger, Ernst Steinhoff, whose brother was a U-boot commander, came up with the idea to launch solid-propellant rockets from a submerged submarine.[28] Ernst Steinhoff was the Director for Flight Mechanics, Ballistics, Guidance Control, and Instrumentation at the Peenemünde Army Research Center.[29] His brother Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Steinhoff commanded submarine U-511. Tubular metal launch frames (Schwere Wurfgerät 41 (sWG 41)), carrying a total of six 30 cm Wurfkörper 42 rockets, were mounted on the upper deck of the submarine, with a 45° firing angle.[31][32][33] From 31 May to 5 June 1942,[34] under the code name "project Ursel", a series of solid-fuel rocket launching experiments were carried out using submarine U-511 as a launching platform near the Greifswalder Oie.[35] Successful firings from the surface were carried out on 4 June 1942,[35] and from up to 15 meters underwater without any effect on the missiles' accuracy.[36][37] The rocket system was first envisaged as a weapon against convoy escorts, but with no effective guidance system, the arrangement was ineffective against moving targets and could only be used for shore bombardment.[38] The development of this system ended in early 1943, as it was found to decrease the U-boats' seaworthiness.[39]

From 1944 to 1945, the German Navy continued to develop and successfully tested various short-range rockets that could be launched from submerged submarines up to a depth of 100 meters at the naval testing station operated by the Torpedoversuch Anstalt Eckernförde at the Lake Toplitz, near Bad Aussee, in Austria.[23][40] No official records have been found yet on the deployment of these short-range rockets on German U-boats or its use against targets at sea or ashore.[36]

Of note, the first recorded attack using seabased rockets on shore targets was carried out by the US submarine USS Barb (SS-220) on 22 June 1944 against the Japanese town Shari. The USS Barb fired 12 5-inch rockets Mk 10 Mod 0,[41] from 4,700 yards (4,300 m) offshore, using a rocket launcher Mk 51 Mod 0 installed on the deck of the submarine.[42][43]

V-1 flying bombs

In 1943 interest in the concept of seabased-launched missiles was revived with the advent of the V-1 flying bomb; proposals were made to mount a V-1 and steam-operated launcher on a U-boat to strike targets at a much greater range than the 150 miles (240 km) radius from land-based sites. This proposal foundered on inter-service rivalry, however, as the V-1 was a Luftwaffe project.[44]

In September 1944, the Allies received intelligence reports which suggested that Germany's Kriegsmarine was planning to use V-1 flying bombs launched from submarines to attack cities on the east coast of the United States. A modified German submarine was spotted in a southern Norwegian port "showing a pair of rails extending from conning tower to the bow and terminating at a flat, rectangular surface", apparently modified to launch V-1 flying bombs.[45] Notwithstanding, no official records have been found yet on the deployment of V-1 flying bombs on German U-boats.[36]

V-2 rockets

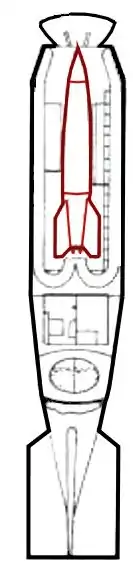

In Autumn 1943, Deutsche Arbeitsfront Director, Bodo Lafferentz, proposed to Dornberger the idea of a towable watertight container that could hold a V-2 rocket.[46][47][48] The project of seabeased of V-2 rockets was code-named Apparat F[21] and the development of towable containers themselves are commonly referred to by the codename Prüfstand XII from late 1944.[49][50] Unmanned and unpowered, the container was intended to be towed by a conventional U-boat to within the range of its target, then set up and launched from its gyro-stabilized platform.[51] A report of the Peenemünde research center dated from 19 January 1945 clearly summarised the objectives of Prüfstand XII: "This project opens up the possibility of attacking, with the Apparat F, off enemy coasts (for example, northern England or eastern America), very distant but strategically important targets that are currently out of range. In addition, it deceives the adversary about the real range of the missile and, at additional costs, offers new strategic and political opportunities."[21] Important rocket scientists such as Klaus Riedel, Hans Hüter, Bernhard Tessman, Georg von Tiesenhausen were assigned to the project.[52]

Once in the firing position, its upper ballasts would be remotely emptied to bring the container from its horizontal towing position to its vertical launching position, with its bow emerging about 5 meters above the surface.[53] The container was stabilized using the large rudders of the container, steered by a gyroscopic system. A service team consisting of three operators would leave the submarine in an inflatable boat, while the fire control unit remained on board the submarine.[54] The operators would open the hinged lid at the bow of the container to get access to a servicing platform and connect the container to the submarine to power it. They would prepare the warhead and fuel the missile with liquid oxygen, ethanol and sodium permanganate for the turbopump, from fuel tanks located in the container. The missile was prepared for launch from the service room located underneath the missile chamber. The V-2 would have been guided by rails and the empty space would accommodate the ballasts. The exhaust jet was deflected 180° using collecting funnels so that the jet could exit upward.[55][56][57] This deflection would in turn reduce the rocket thrust and its radius of action of a seabased V-2 rocket, requiring the u-boat to come dangerously close to the coast. The armed missile would have been ready to launch 30 minutes after reaching its firing position. After the launch, the container could be abandoned or towed back to the base.[54]

Initial calculations showed that a U-boat could tow, at periscope depth and at a speed of 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph), three submerged containers at a time.[28] An attack on US targets would require a 30-day trip yo the launching position at an average speed of 10–12 knots (19–22 km/h; 12–14 mph).[21][28] Type XXI U-boats, with a range of 15,500 nautical miles (28,700 km; 17,800 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) surfaced and 340 nmi (630 km; 390 mi) at 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) submerged, were considered to be the ideal submarines to perform such attacks on US soil.

This project was delayed until November 1944 due to troubles in the development of V-2.[28] In January 1945, Dornberger submitted over a hundred detailed draft designs.[21] A 300-ton prototype was built by Schichau-Werke GmbH.[46] At the beginning of 1945, successful underwater towing trials were carried out with U-boat 1063.[58]

Although its design never reached the prototype stage, the engineers of Peenemünde considered using the A-8 version of the V-2 rocket. It was a "stretched" variant of the V-2 with a longer radius of action that used rocket propellants like nitric acid oxidizer and kerosene pressurized with nitrogen, if the losses of hydrogen peroxide could not be kept under 1% per day as planned.[54][21] This called for longer containers weighing 500 tons and measuring 32 meters long.[46] Under the code-name "Projekt Schwimmweste" (English: Project Lifejacket), confidential reports, dated 3 January 1945 and 19 January 1945, indicate that the Stetinner Vulkanwerft (English: Vulkan Docks) was contracted to build three containers in Stetin by March 1945 and that four test firings were planned with different firing configurations.[21][59]

The evacuation of Peenemünde in February 1945 and the fall of Stettin to the Red Army in April 1945 brought an end to these developments. There are no records that these were tested with a rocket launch before Germany's final collapse.[60][50]

The fate of these containers after the war is uncertain. According to some sources, incomplete capsules and design information were captured by Soviet forces.[46] Reportedly, the project was continued with the assistance of German scientists and lead to the development of GOLEM-1, a liquid-fueled rocket, based on the V-2 rocket design and designed to be launched from a capsule towed by a submarine.

According to Michael Neufeld, although generously described as a forerunner of the ballistic missile submarines, the idea of launching V2-rockets from canisters towed by U-boats across the Atlantic Ocean embodied the mood of the desperation of Nazi Germany at the end of World War II, concluding that "it is hard to see how a few [V-2 rocket attacks on New York] would have done anything but make Americans more determined to take revenge on German cities".[50] Frederick Ira Ordway III and Michael Sharpe considered this project "became a part of the history that may have been, given more time".[52]

Fears for rocket attacks on US

Rumors of missile-armed submarines, operating from Bergen with New York as the target, emerged at the end of 1944, including one from Denmark and one from Sweden passed on by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.[61][62] The British Admiralty discounted these reports and assessed that while V-1s could be potentially mounted on Type IX submarines, the Germans were unlikely to devote scarce resources to such a project.[63] The press reported in May 1945 an attempted attack on New York on the 1944 election day with a "jet-propelled or rocket-propelled weapon" from submarines. The US Navy declared that the report of the submarine attack was "without foundation".[64]

German spies William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel were landed in Maine on 29 November 1944 by the Type IXC/40 U-boat U-1230 to gather intelligence on U.S. military and technology facilities. Colepaugh was arrested on 6 December. During his interrogation, Colepaugh claimed that German U-boats were being equipped with long-range rocket launchers.[65] Supposedly, the U-1230 was shadowed by a U-boat pack equipped with such V-weapons intended to attack New York City and Washington D.C. Although the US took the threat seriously, it never materialized,[66] and Colepaugh's claim was later proven false.[65]

The Atlantic Fleet's commander, Vice Admiral Jonas H. Ingram, gave a press conference on 8 January 1945 in which he warned there was a threat of a missile attack and announced that a large force had been assembled to counter seaborne missile launchers.[67][68][69][70] In January 1945, German Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer made a propaganda broadcast in which he claimed that V-1 and V-2s "would fall on New York by February 1, 1945", increasing the U.S. Government's concern over the threat of attack.[71]

In response to this threat, the US navy conducted Operation Teardrop, between April and May 1945, to sink German U-boats detected heading for the Eastern Seaboard believed to be armed with V-1 flying bombs or V-2 rockets. Five of the seven Type IX submarines that stationed off the United States were sunk, four with their entire crews. Thirty-three U-546 crew members were captured. Following the end of World War II in Europe, the submarines U-234, U-805, U-858 and U-1228 surrendered at sea before returning to bases on the U.S. east coast.[72][73]

After the German surrender, the U.S. Navy continued its efforts to determine whether the U-boats had carried missiles. The crews of U-805 and U-858 were interrogated and confirmed that their boats were not fitted with missile launching equipment.[74] Kapitänleutnant Fritz Steinhoff, who had commanded U-511 during her rocket trials and was captured at sea when he surrendered U-873, was subjected to an abusive interrogation at Portsmouth by the interviewers of U-546's crew. On 19 May 1945, Steinhoff bled to death in his Boston jail cell from wrist wounds, possibly self-inflicted with the broken lens of his sunglasses.[75][76][32][77] It is not known if the Allies were aware of Steinhoff's involvement in the rocket trials.[74][78] Six months after Steinhoff's death, his brother Ernst Steinhoff was one of the Operation Paperclip rocket scientists from Peenemünde arriving in the United States to work at White Sands Missile Range.[79]

Post-war developments

Soviet Union

After the war, Western experts were convinced that the Soviet Union had developed the sea-going GOLEM 1 rocket based on the V-2 rocket.[80][81][82] Developed with the assistance of German scientists, GOLEM 1, details are scarce but it is believed that the underwater-to-surface GOLEM-1 rocket was nuclear-capable, liquid-fueled (oxygen and alcohol), radio-inertial guided rockets designed to be launched from a capsule towed by a submarine.[83][84] The GOLEM-1 was a 53.8-foot (16.4 m) long rocket with a diameter of 5.41 ft (1.65 m) and a range of 395 mi (636 km).[85] Two or three GOLEM-1 missiles could be towed in capsules by submerged submarines.[83]

The Soviet submarine B-67, a converted Project 611 (Zulu-IV class) submarine, launched on 16 September 1955 at 17:32 in the White Sea, the world's first submarine-launched ballistic missile: an R-11FM (SS-N-1 Scud-A), the naval variant of the R-11 Zemlya (SS-1b Scud-A), modeled after the Wasserfall, the anti-aircraft version of the V-2 rocket and developed by engineer Victor Makeev.[86][87] The missiles were too long to be contained in the boat's hull and extended into the enlarged sail.[88] To be fired, the submarine had to surface and raise the missile out of the sail.[89] Five additional Project V611 and AV611 (Zulu-V class) submarines became the world's first operational ballistic missile submarines with two R-11FM missiles each, entering service in 1956–57.[90][91] Six Zulu class submarines successfully modified to carry and launch three R-11FM missiles became known by their NATO reporting name of Golf class.

Following this initial success, the R-11FM was further developed and the first underwater launch of a modified R-11FM rocket, using solid instead of liquid fuel, took place on 26 December 1956 from a 30 m depth from an immersed platform. With a range of 150 km and a payload of 967 kg, the R-11FM rocket officially entered service in the Navy on 20 February 1959.[88] The Soviet Union made its first successful underwater launch of a submarine ballistic missile in the White Sea, on 10 September 1960 from the same converted Project 611 submarine that first launched the R-11FM.[92]

United States

During Operation Sandy, for the first time, a German V-2 rocket, seized by the US Army at the end of the war in Germany, was launched from a ship at sea, several hundred miles south of Bermuda. The first sea launch of a V-2 rocket took place on 6 September 1947 from the upper deck of the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CV-41).[93] The first seabased launch of a missile was executed by the US Navy on 12 February 1947 from the upper deck of the US submarine USS Cusk (SS-348).[94] Codenamed "loon", a naval version of the Republic-Ford JB-2, a reversed-engineered copy of the German V-1 flying bomb, was successfully launched off Point Mugu, California. The JB-2 "Loon" was developed to be carried on the aft deck of submarines in watertight containers. USS Carbonero (SS-337) was modified to provide mid-course guidance for JB-2 "Loon".[95] These successful tests led to the development of submarine-launched cruise missiles.[96] The U.S. Navy's success in adapting a variant of the V-1 to be launched from submarines also demonstrated that it would have been technically feasible for the German navy to have done the same.[97]

- Seabased launch of JB-2 "Loon" cruise missiles by the US Navy

_V-2_launch_(Operation_Sandy).jpg.webp) Launch of a captured V-2 rocket from deck of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Midway (CVB-41) during "Operation Sandy", 6 September 1947

Launch of a captured V-2 rocket from deck of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Midway (CVB-41) during "Operation Sandy", 6 September 1947.tiff.jpg.webp) First launching on 12 February 1947, off Point Mugu, California, from USS Cusk of an LTV-N-2 Loon missile, a US copy of the German V-1 flying bomb

First launching on 12 February 1947, off Point Mugu, California, from USS Cusk of an LTV-N-2 Loon missile, a US copy of the German V-1 flying bomb A JB-2 "Loon" being fired from USS Cusk in 1951

A JB-2 "Loon" being fired from USS Cusk in 1951

By 1953 the USS Tunny had been adapted into a true missile submarine, but it was still an awkward process to firing the Regulus cruise missile, a nuclear-capable turbojet-powered second-generation cruise missile that outgrew from the tests conducted with the German V-1 flying bomb. The submarine had to surface, then the missile was manually loaded from storage onto a launch rail on the submarine's deck before it could fire. During the entire process, the surfaced submarine was visible and vulnerable to attack by enemy aircraft. The Grayback-class submarines were subsequently built to launch missiles from the surface. On the Graybacks, two missile hangars allowed for a total of two Regulus II or four Regulus I missiles each.

- Seabased launch of Regulus I missiles by the US Navy

_Regulus_launching_sequence_c1956.jpg.webp) USS Tunny fires a Regulus I missile (c. 1956)

USS Tunny fires a Regulus I missile (c. 1956) USS Grayback preparing to launch a Regulus II missile (c. 1960)

USS Grayback preparing to launch a Regulus II missile (c. 1960)

The United States's first operational ballistic missile submarine, the USS George Washington, standing out into the Atlantic Missile Test Range successfully conducted the first UGM-27 Polaris missile launch from a submerged submarine on 20 July 1960, establishing the nuclear deterrent role of missile submarines.[98] USS George Washington also conducted the first successful submerged SLBM launch with a Polaris A-1 on 20 July 1960.[99]

In March 2010, Deputy Secretary of Defense William J. Lynn III referred to the "Project Laffarenz" (sic) in a speech on missile defense stating that "although Project Laffarenz did not come to fruition, it illustrates how our adversaries will always be reaching for new and ingenious ways to cause us harm. Their tactics may make straightforward use of weapons systems we are prepared to defend against. But they may also marry high and low technologies in unexpected combinations, forcing us to quickly adapt."[100][101]

See also

- USS Barb (SS-220)

- Japanese I-400-class submarine aircraft carrier

- Japanese Type AM submarine aircraft carrier

References

- Ash, E. (1999). "Terror Targeting. The Morale of the Story" (PDF). Aerospace Power Journal.

- Goda, Paul J. (1966). "The Protection of Civilians from Bombardment by Aircraft: The Ineffectiveness of the International Law of War". Military Law Review. 33.

- Grayling 2006, p. 50-51.

- Boog 2001, p. 566.

- Hastings 1979, pp. 146-148.

- Terraine 1985, pp. 472-478.

- Price 1977, p. 132.

- Price 1977, p. 136.

- Boog 2001, p. 380.

- Collier 1976, p. 138.

- "V-Weapons Crossbow Campaign". All World Wars. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Collier 1976, p. 15–16.

- Werrell 1985, pp. 41–62.

- Zaloga 2005, p. 7.

- "Long-range" in the context of the time. See NASA Kennedy Space Center (24 August 2000l). "A Brief History of Rocketry". Archived from the original on 7 January 2009.

- Neufeld 1995, p. 73, 74, 101, 281.

- Dungan, T. "The A4-V2 Rocket Site". Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Werrell 1985, p. 42.

- Henshall 1985, p. 128.

- Johnson 1982, p. 80.

- Marion, Jehan (3 April 2020). "Des U Boote lance-missiles ?" [Missile-launching U-boats?] (PDF). Plongée illustrée (in French). Association Générale des Amicales de Sous-Mariniers: 1–13.

- Duffy 2004, p. 95-98.

- Griehl 2006, p. 228–232.

- "Hitler's Rocket U-boat Program – history of WW2 rocket submarine". German U-Boats and Battle of the Atlantic. 2016. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- "The First Submarine Launched Rockets". Prinzeugen.com. 2011-07-24. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Geise, Gernot L. (2006). "Geheime Waffen, Geräte und andere Erfindungen im 2. Weltkrieg" [Secret weapons, devices and other inventions in World War II] (PDF). Efedon: Synesis (in German). 75 (3): 44–51. ISSN 0945-1366.

- Geise, Gernot L. (2007). "Geheim- und Sonderwaffen im 2. Weltkrieg" [Secret and special weapons in World War 2] (PDF). Efedon: Synesis (in German). 81 (3): 15–20. ISSN 0945-1366.

- Dornberger 1958, p. 231–237.

- International Space Hall of Fame. "Ernst A. Steinhoff". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Stoelzel, Heinz (1982). "Die deutschen Raketen-U-Boote". Schiff und Zeit (in German). Deutschen Gesellschaft für Schifffahrts- und Marinegeschichte. 16: 1–3.

- Lawton 2019.

- Rider 2020, p. 3875-3883.

- Prag 2009, p. 165–166.

- Paterson 2009, p. 55–57.

- "U 511 and Missiles – U 511, U 1063 and plans for U-boats armed with seabased missiles". Deutsches U-Boot-Museum. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- Rider 2020, p. 3873.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "The Type IXC boat U-511". German U-boats of WWII – uboat.net. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Lundeberg 1994, pp. 213–214.

- Köberl 1990, p. 78-80.

- "Navy Rockets". U.S. Explosive Ordnance. Ordnance Pamphlet 1644. US Navy. 1947. p. 173.

- "USS Barb rocket attack question". models.rokket.biz. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

On their 12th war patrol the Barb had a Mk 51 Mod 0 launcher and 72 Mk 10 Mod 0 5-inch rockets. They launched a total of 4 rocket assaults and fired a total of 68 rockets... The rocket launcher was mounted on the foredeck in the area where the 4 inch gun had previously been mounted... (...) The 1st rocket assault on the town of Shari occurred on 6/22/1945 at 2:34 am. The Barb launched 12 rockets into the center of the town from 4,700 yds offshore...

- "Rocket launcher Mk 51 Mod 0". Missile Launchers and Related Equipment Catalog. Ordnance Pamphlet 1855. US Navy. 1953.

- Marion, Jehan (3 April 2020). "Des U Boote lance-missiles ?" [Missile-launching U-boats?] (PDF). Plongée illustrée (in French). Association Générale des Amicales de Sous-Mariniers: 1–13.

- Rider 2020, Interpretation report n° S103 (p. 3867-3868; E.2.4 Submarine-Launched and Solid Propellant Rockets).

- Klee & Merk 1965, p. 92-108.

- Dornberger 1958, p. 231– 237.

- Hahn 1998.

- "Prüfstand XII Raketen Unterseeboot". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Neufeld 1995, p. 255.

- Bergaust, Erik (2017). Wernher von Braun. Stackpole Books. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-8117-6623-4.

- Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 55.

- Hahn 1998, p. 172.

- Schoenenberg, Hans (May 1958). "Missile-carying submarines – A new factor of strategic planning". Supplement to Military Review – Professional Journal of the United States Army. Command and General Staff School: 102–106.

- Duffy 2004, p. Towing Missiles to America - p. 95-98.

- Rider 2020, p. 3890-38981944 drawings from the “Prüfstand XII” project to transport and launch V-2 rockets towed in containers by submarines [Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg RH 8/4067K].

- Rider 2020, p. 3890-3898 (Bundesarchiv Militararchiv Freiburg RH 8/4067K).

- Georg 2003, p. 91.

- Brooks 2008, p. 29–30.

- Paterson 2009, p. 57–58.

- Henshall 2000, p. 164-165.

- Georg & Mehner 2004, p. 209.

- Lundeberg 1994, pp. 213–215.

- "U-Boat Aimed V-Bomb Here, Army Paper Says". The New York Times. 1945-05-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

A German submarine tried to V-bomb New York last election day, presumably with a jet-propelled or rocket-propelled weapon, the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes reported tonight

- Miller 2013.

- Breuer 2003, p. 174-176.

- "Robot Bomb Attacks Here Held 'Probable' by Admiral; WARNS OF ROBOT BOMBS". The New York Times. 1945-01-09. p. 1, 6. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- "BOMBS FOR NEW YORK?". The New York Times. 1945-01-10. p. 22. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- Lundeberg 1994, pp. 215–216.

- Siegel 1989.

- Blair 1998, p. 683.

- Y'Blood 2004, p. 272.

- "H-047-1: The Last Battle of the Atlantic—Operation Teardrop". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- Lundeberg 1994, p. 227.

- "Suicide: U-Boat 873 Commander Friedrich Steinhoff". Bill Milhomme. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- Lundeberg, Philip K. (2016). "The Treatment of Survivors and Prisoners of War, at Sea and Ashore". International Journal of Naval History. 16 (1).

- "U-boat Archive – U-873". www.uboatarchive.net. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Blair 1998, pp. 689–690.

- "Steinhoff, Ernst". Astronautix. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Zaloga 1993, p. 171.

- United States Department of the Army 1962, p. 100.

- "Russia's Guided Missile Program". Missiles and Rockets. Vol. 2 no. 2. Washington: American Aviation Publications. 1957. pp. 34–36. ISSN 0096-9702. OCLC 1887163.

- United States Department of the Army 1960, p. 43.

- Parry 1960, p. 154, 161.

- United States Department of the Army 1960, p. 46.

- Wade, Mark. "R-11". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Zapolskiy, Anatoliy Aleksandrovich (1994). "Missiles Take Off From the Sea". fas.org. Podvodnoye Korablestroyeniye. Proshloye, Nastoyashcheye, Budushcheye ("Submarine Building. Past, Present, Future"). Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- "Rocket R-11". RSC "Energia". Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Polmar & White 2010, p. 20.

- Polmar & Moore 2004.

- "Large submarines – Project 611". russianships.info.

- Dygalo, V.A. "Start razreshaju (in Russian)". Nauka i Zhizn'. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "Pictures of Operation SANDY". www.midwaysailor.com. 1947. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- Hambling, David (2017-02-13). "Launching a Missile From a Submarine Is Harder Than You Think". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- Stumpf 2006, p. 13.

- Polmar & Moore 2004, p. 87.

- Duffy 2004, p. 72.

- "Submarine Chronology". Chief of Naval Operations. Submarine Warfare Division. 3 March 2001. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- "Missiles 1963", Flight International: 752, 7 November 1963

- Lynn, William J. (22 March 2010). "Speech: AIAA Conference on Missile Defense As Delivered by Deputy Secretary of Defense William J. Lynn, III, Ronald Reagan International Trade Center, Washington, D.C., Monday, March 22, 2010". US DoD. Archived from the original on 2010-04-15. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- "Danger Room Mythbuster: Nazi Rocket Barge, Sunk". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

Bibliography

- Blair, Clay (1998). Hitler's U-Boat War. The Hunters, 1942–1945 (Modern Library ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-64033-9.

- Boog, Horst (2001). The Global War. Germany and the Second World War. VI. Oxford University Press. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-19-822888-2.

- Brooks, Geoffrey (2008). Hitler's Terror Weapons: From VI to Vimana. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-78337-933-0.

- Breuer, William B. (2003). The air-raid warden was a spy and other tales from home-front America in World War II. Hoboken, N.J. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-23488-3.

- Collier, Basil (1976). The Battle of the V-weapons, 1944–45. Elmfield Press. ISBN 978-0-7057-0070-2.

- Dornberger, Walter (1958). V-2: The Nazi Rocket Weapon. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-345-06273-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffy, James P. (2004). "U-boats to America". Target America : Hitler's plan to attack the United States. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96684-4. OCLC 53476807.

- Georg, Friedrich (2003). Hitler's Miracle Weapons: The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-91-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Georg, Friedrich; Mehner, Thomas (2004). Atomziel New York : geheime Grossraketen- und Raumfahrtprojekte des Dritten Reiches [Atomic Target New York: Secret Large Rocket and Space Projects of the Third Reich] (in German). Rottenburg: Kopp. ISBN 978-3-930219-91-9.

- Grayling, A. C. (2006). Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-7671-8.

- Griehl, Manfred (2006). "Rocket attack". Luftwaffe over America : the secret plans to bomb the United States in World War II. London: Greenhill. ISBN 0-7607-8697-6. OCLC 156852663.

- Hahn, Fritz (1998). Waffen und Geheimwaffen des deutschen Heeres 1933–1945 (in German). Bonn: Bernard und Graefe. ISBN 978-3-89555-128-4.

- Hastings, Max (1979). Bomber Command. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-39204-2.

- Henshall, Philip (1985). Hitler's Rocket Sites. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 128.

- Henshall, Philip (2000). The Nuclear axis : Germany, Japan and the atom bomb race, 1939–1945. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Pub. ISBN 0-7509-2293-1.

- Johnson, David (1982). V-1, V-2: Hitler's Vengeance on London. Stein and Day. ISBN 0-8128-2858-5.

- Köberl, Markus (1990). "Das Projekt "Ursel"". Der Toplitzsee: wo Geschichte und Sage zusammentreffen (in German). ÖBV. ISBN 978-3-215-07491-2.

- Klee, Ernst; Merk, Otto (1965). The Birth of the Missile: The Secrets of Peenemünde. Dutton.

- Lawton, Paul M. (18 November 2019). Hitler's Raketen U-Boote (Rocket Submarines) : the true story of the Steinhoff Brothers and the Nazi's first submarine launched missiles : the untold New England U-Boat saga and murder mystery. Brockton, MA. ISBN 978-1-938394-39-3. OCLC 1198434716.

- Lundeberg, Philip K. (1994). "Operation Teardrop Revisited". In Runyan, Timothy J.; Copes, Jan M (eds.). To Die Gallantly : The Battle of the Atlantic. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8815-5.

- Miller, David (2000). U-boats : history, development and equipment 1914–1945. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-790-2.

- Miller, Robert A. (2013). A true story of an American Nazi spy : William Curtis Colepaugh. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-8220-8. OCLC 828892911.

- Neufeld, Michael J. (1995). The Rocket and the Reich. Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-922895-6.

- Ordway, Frederick Ira; Sharpe, Mitchell R. (1979). The Rocket Team. Crowell. ISBN 978-0-690-01656-7.

- Parry, Albert (1960). Russia's Rockets and Missiles. Doubleday.

- Paterson, Lawrence (2009). Black flag : the surrender of Germany's U-boat forces. Minneapolis, Minn.: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3754-7. OCLC 308175284.

- Polmar, Norman; Moore, Kenneth J. (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-594-1.

- Polmar, Norman; White, Michael (2010-11-29). Project Azorian: The CIA and the Raising of the K-129. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-690-2. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Prag, Christian (16 April 2009). No Ordinary War: The Eventful Career of U-604. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-022-2.

- Price, Alfred (1977). Blitz on Britain 1939–1945. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0723-3.

- Rider, Todd H. (1 June 2020). Forgotten Creators – How German-Speaking Scientists And Engineers Invented The Modern World, rev. 2020-06-01.

- Siegel, Adam B. (1989). "The Wartime Diversion of U.S. Navy Forces in Response to Public Demands for Augmented Coastal Defense". HyperWar Project.

- Stumpf, David (2006). Regulus, the forgotten weapon : a complete guide to Chance Vought's Regulus I and II. Paducah, KY: Turner Pub. Co. ISBN 978-1-59652-183-4.

- Terraine, John (1985). The Right of the Line. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-26644-9.

- United States Department of the Army (28 September 1960). USSR: Missiles, Rockets, and Space Effort, a Bibliographic Record, 1956–1960. DA Pamphlet 70-5-8. Washington, DC.

- United States Department of the Army (1962). Missiles and ventures into space: Progress report, 1961–1962. Washington, DC: U.S. G.P.O.

- U.S. Naval Technical Mission in Europe (16 October 1945). German Underwater Rockets (Report). 500–45.

- Werrell, Kenneth P. (1985). The Evolution of the Cruise Missile (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press.

- Y'Blood, William T. (2004). Hunter-killer: U.S. escort carriers in the Battle of the Atlantic (illustrated ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-995-9.

- Zaloga, Steven (1993). Target america : the soviet union and the strategic arms race, 1945–1964. Diane Pub Co. ISBN 978-0-7881-6725-6.

- Zaloga, Steven (2005). V-1 Flying Bomb 1942–52. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-791-8.