Roger Fenton

Roger Fenton (28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869) was a British photographer, noted as one of the first war photographers.

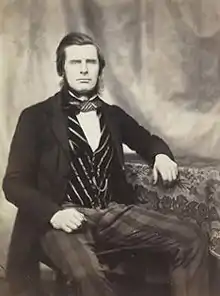

Roger Fenton | |

|---|---|

Fenton, Self-portrait | |

| Born | 28 March 1819 Heywood, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 8 August 1869 (aged 50) Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of London; Charles Lucy, Paris |

| Known for | Photographer and painter |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Elizabeth Maynard |

Fenton was born into a Lancashire merchant family. After graduating from London with an Arts degree, he became interested in painting and later developed a keen interest in the new technology of photography after seeing early examples at The Great Exhibition in 1851. Within a year, he began exhibiting his own photographs. He became a leading British photographer and instrumental in founding the Photographic Society (later the Royal Photographic Society). In 1854, he was commissioned to document events occurring in Crimea, where he became one of a small group of photographers to produce images of the final stages of the Crimean War.

Early life

Fenton was born in Crimble Hall, Heywood, Lancashire, on 28 March 1819. His grandfather was a wealthy cotton manufacturer and banker, whilst his father, John, was a banker and from 1832 a member of parliament.[1] Fenton was the fourth of seven children by his father's first marriage. His father had 10 more children by his second wife.

In 1840 Fenton graduated with a "first class" Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of London,[2] having read English, mathematics, Greek and Latin. In 1841, he began to read law at University College, London, evidently sporadically as he did not qualify as a solicitor until 1847, partly because he had become interested in learning to be a painter. In Yorkshire in 1843 Fenton married Grace Elizabeth Maynard, presumably after his first sojourn in Paris (his passport was issued in 1842) where he may briefly have studied painting in the studio of Paul Delaroche. When he registered as a copyist in the Louvre in 1844 he named his teacher as the history and portrait painter Michel Martin Drolling, who taught at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, but Fenton's name does not appear in the school records. By 1847 Fenton had returned to London where he continued to study painting under the tutelage of the history painter Charles Lucy, who became his friend and with whom, starting in 1850, he served on the board of the North London School of Drawing and Modelling. In 1849, 1850 and 1851 he exhibited paintings in the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy.

Fenton visited the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in London in 1851 and was impressed by the photography on display there. He then visited Paris to learn the waxed paper calotype process, most likely from Gustave Le Gray who had modified the methods employed by William Henry Fox Talbot, its inventor. By 1852 he had photographs exhibited in Britain, and travelled to Kiev, Moscow and St. Petersburg, and also photographed views and architecture around Britain. His published call for the setting up of a photographic society was answered in 1853 with the establishment of the Photographic Society, with Fenton as founder and first Secretary. It later became the Royal Photographic Society under the patronage of Prince Albert.[4][5]

Crimean War

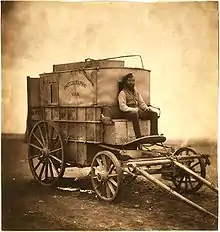

It is likely that in autumn 1854, as the Crimean War grabbed the attention of the British public, that some powerful friends and patrons – among them Prince Albert and Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State for War – urged Fenton to go to the Crimea to record the happenings. The London print publisher Thomas Agnew & Sons became his commercial sponsor.[6][7] The resulting photographs may have been intended to offset the general unpopularity of the war among the British people, and to counteract the occasionally critical reporting of correspondent William Howard Russell of The Times;[8][9] the photographs were to be converted into woodblocks and published in the less critical Illustrated London News. He set off aboard HMS Hecla in February, landed at Balaklava on 8 March and remained there until 22 June. Fenton took Marcus Sparling as his photographic assistant, a servant known as William and a large horse-drawn van of equipment.

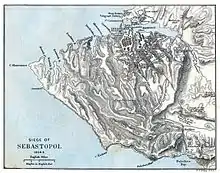

Due to the size and cumbersome nature of his photographic equipment, Fenton was limited in his choice of motifs. Because the photographic material of his time needed long exposures, he was only able to produce pictures of stationary objects, mostly posed pictures; he avoided making pictures of dead, injured or mutilated soldiers. But he also photographed the landscape, including an area near to where the Charge of the Light Brigade – made famous in Tennyson's poem – took place. In letters home soldiers had called the original valley "The Valley of Death", and Tennyson's poem used the same phrase, so when in September 1855 Thomas Agnew put the picture on show, as one of a series of eleven collectively titled Panorama of the Plateau of Sebastopol in Eleven Parts in a London exhibition, he took the troops'—and Tennyson's—epithet, expanded it as The Valley of the Shadow of Death with its deliberate evocation of Psalm 23, and assigned it to the piece; it is not the location of the famous charge, which took place in a long, broad valley several miles to the south-east.[10][11]

In 2007 film-maker Errol Morris went to Sevastopol to identify the site of this "first iconic photograph of war". He identified the small valley, shown on a later map as "The Valley of the Shadow of Death", as the place where Fenton had taken his photograph (see right). Two pictures were taken of this area, one with several cannonballs on the road, the other with an empty road. Hitherto opinions differed concerning which one was taken first but Morris spotted evidence that the photo without the cannonballs was taken first.[12][13][14] He remains uncertain about why balls were moved onto the road in the second picture—perhaps, he notes, Fenton probably deliberately placed them there to enhance the image. The alternative is that soldiers were gathering up cannonballs for reuse and they threw down balls higher up the hill onto the road and ditch for collection later. Other art historians, such as Nigel Spivey of Cambridge University, identify the images as from the nearby Woronzoff Road. In June 1855 illustrator and war correspondent William Simpson produced a watercolour of the Woronzoff Road, but looking downhill, which has cannonballs similarly placed to those shown by Fenton; Simpson's publisher too used the title "The Valley of the Shadow of Death".[15] This is the location accepted by the local tour guides.[16][17]

Despite summer high temperatures, breaking several ribs in a fall, suffering from cholera and also becoming depressed at the carnage he witnessed at Sevastopol, in all Fenton managed to make over 350 usable large format negatives. An exhibition of 312 prints was soon on show in London and at various places across the nation in the months that followed. Fenton also showed them to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and also to Emperor Napoleon III in Paris. Nevertheless, sales were not as good as expected.

Post Crimea

Despite the lack of commercial success for his Crimean photographs, Fenton later travelled widely over Britain to record landscapes and still life images. However, as time moved on, photography became more accessible to the general public. Many people sought to profit from selling quick portraits to common people. It is likely that Fenton, from a wealthy background, disdained 'trade' photographers, but nevertheless still wanted to profit from the art by taking exclusive images and selling them at good prices. He thus fell into conflict with many of his peers who genuinely needed to make money from photography and were willing to 'cheapen their art' (as Fenton saw it), and also with the Photographic Society, who believed that no photographer should soil himself with the 'sin' of exploiting his talent commercially in any manner.

Amongst Fenton's photographs from this period are the City of Westminster, including The Palace of Westminster nearing completion in 1857 – almost certainly the earliest images of the building, and the only photographs showing the incomplete Clock Tower.

Later work

In 1858 Fenton made studio genre studies based on romantically imaginative ideas of Muslim life, such as Seated Odalisque, using friends and models who were not always convincing in their roles.[18] Although well known for his Crimean War photography, his photographic career lasted little more than a decade, and in 1862 he abandoned the profession entirely, selling his equipment and returned to the law as a barrister.[1] Although becoming almost forgotten by the time of his death seven years later he was later formally recognised by art historians for his pioneering work and artistic endeavour.[4]

In 1862 the organising committee for the International Exhibition in London announced its plans to place photography, not with the other fine arts as had been done in the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition only five years earlier, but in the section reserved for machinery, tools and instruments – photography was considered a craft, for tradesmen. For Fenton and many of his colleagues, this was conclusive proof of photography's diminished status, and the pioneers drifted away.

He died 8 August 1869 at his home in Potters Bar, Middlesex after a week-long illness – he was only 50 years old. His wife died in 1886. Their graves were destroyed in 1969 when the Potters Bar church where they were buried was deconsecrated and demolished.

References

- Taylor, Roger (October 2006). "Fenton, Roger (1819–1869)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- "Admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts First Division". Examination and matriculation papers: 1838–43. University of London. 1843. p. 81. OCLC 38086382.

- Library of Congress: Roger Fenton Crimean War Photographs

- Royal Photographic Society

- Macdonald, Gus (1980). Camera. Victorian Eyewitness : a History of Photography, 1826–1913. London: Viking. p. 10.

- Deazley, Ronan. Derclaye, Estelle (ed.). Copyright and Cultural Heritage: Preservation and Access to Works in a Digital World. Cheltenham, England: Elgar. p. 96. ISBN 9781849808033.

- Gernsheim, Helmut; Gernsheim, Alison (1954). Roger Fenton, photographer of the Crimean War. London: Secker & Warburg. pp. 13–17. OCLC 250629696.

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003; ISBN 0-374-24858-3)

- The valley, called the "North Valley" by the British military, was just less than a mile wide and about a mile and a quarter long: Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1953). The Reason Why. London: John Constable. p. 238. OCLC 504665313.

- Green-Lewis, Jennifer (1996). Framing the Victorians: Photography and the Culture of Realism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-8014-3276-6.

- Morris, Errol (2011). Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography. Chapter 1: Penguin Press. p. 310. ISBN 9781594203015.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Morris, Errol (5 October 2012). "In the Valley of the Shadow of Doubt". RadioLab. WNYC Radio. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Dicker, Ron (1 October 2012). "'Valley Of The Shadow Of Death,' Famous Early War Photo, A Staged Fake, Investigator Says (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Simpson, William (1855). "The valley of the shadow of death Caves in the Woronzoff Road behind the 21 gun battery /". Library of Congress. Colnaghi brothers. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Morris, Errol (25 September 2007). "Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?" (PDF). Museum of Texas Tech University. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Spivey, Nigel (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-520-23022-1.

- Hoffman, Katherine (2008). Hannavy, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. 1. New York: Taylor and Francis. p. 1031. ISBN 9780415972352.

Further reading

- Baldwin, Gordon; et al. (2004). All the mighty world: the photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852–1860. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588391285.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roger Fenton. |