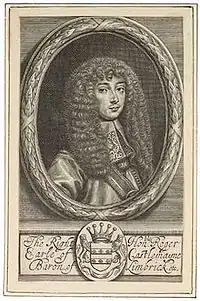

Roger Palmer, 1st Earl of Castlemaine

Roger Palmer, 1st Earl of Castlemaine, PC (1634–1705) was an English courtier, diplomat, and briefly a member of parliament, sitting in the House of Commons of England for part of 1660. He was also a noted Roman Catholic writer. His wife Barbara Villiers was one of Charles II's mistresses.

Early life

Born into a Catholic family, Roger was the son of Sir James Palmer of Dorney Court, Buckinghamshire, a Gentleman of the Bedchamber under King Charles I, and Catherine Herbert, daughter of William Herbert, 1st Baron Powis. He was educated at Eton College and King's College, Cambridge. He was admitted at the Inner Temple in 1656.[1]

In March 1660, Palmer was elected Member of Parliament for Windsor in the Convention Parliament. Following a double return, he was not seated until 27 April.[2]

Barbara Villiers

In 1660 Barbara Villiers, his wife of one year, became mistress to King Charles II. The king created Palmer Baron Limerick and Earl of Castlemaine in 1661, but the title was limited to his children by Barbara (as opposed, that is, to any later wife he might have) which made it clear to the whole court that the honour was for her services in the King's bedchamber rather than for his in the King's court. This made it more of a humiliation than an honour:

[...] and then to the Privy Seal, and sealed there the first time this month; and, among other things that passed, there was a patent for Roger Palmer (Madam Palmer's husband) to be Earl of Castlemaine and Baron of Limbricke in Ireland; but the honour is tied up to the males got of the body of this wife, the Lady Barbary: the reason whereof every body knows.

Palmer did not want a peerage on these terms, but it was forced on him; and he never took his seat in the Irish House of Lords (although he did use the title).

Career

While on a prolonged tour in France and Italy, he served as an officer in the fleet of the Venetian Republic in 1664 before returning to England later that year. In 1665 he served under the Duke of York in the Royal Navy during the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[3]

Palmer showed unwavering and public devotion to Roman Catholicism, in spite of heavy legal and social penalties, and also staunchly supported the Stuart monarchy. His loyalty to the throne and the Stuart succession in general and to the person of Charles II in particular forced his acquiescence to his wife's position as the King's mistress.

As a prominent Roman Catholic, Castlemaine came under suspicion at the time of the Popish plot alleged by Titus Oates and others. In the atmosphere of anti-Catholic hysteria of the time, Palmer was committed to the Tower of London and subsequently tried at the King's Bench Bar in Westminster for high treason. He had to represent himself and, as shown by the verbatim account in the State Trials, secured his own acquittal with skilful advocacy in his own defence against Judge Jeffreys and Chief Justice Scroggs.

He became a member of the English Privy Council in 1686, following James II's accession to the throne. He was appointed Ambassador to the Vatican, where he was ridiculed as Europe's most famous cuckold.[4] As ambassador, he promoted James's plan to have Pope Innocent XI make his Jesuit privy councillor, Edward Petre, a cardinal. Innocent declined to do so.[5][6]

After the Revolution of 1688, Castlemaine fled for refuge to Llanfyllin near his ancestral home in Montgomeryshire and stayed for a while in the house of a recusant there,[7] but he was arrested in Oswestry, Shropshire, and committed to the Tower,[8] spending most of 1689 and part of 1690 there. After enduring almost 16 months in the Tower, he was freed on bail. He was arrested and sent to the Tower again in 1696 after failing to attend the Irish Parliament but was released again 5 months later.[9]

Later life

He died quietly in Oswestry in 1705 at the age of 70, and was buried in the Herbert family vault at St Mary's Church, Welshpool, Montgomeryshire.[10] His estranged wife Barbara followed him to the grave four years later in 1709. Castlemaine's heirs included his nephew, Charles Palmer of Dorney Court, to whom he left property in Wales which had come to him from his mother's family, but it proved to be heavily encumbered and worth little.

His titles became extinct at his death. His wife's sons might technically have claimed them since they were all born while she remained married to him, and there is a presumption of legitimacy in marriage, but no-one ever contended that they were in fact legitimate and no such claim was ever made. The sons had, in any event, all been granted titles of their own by Charles II.

The writings of Roger Palmer, Earl of Castlemaine, include the Catholique Apology (1666), The Compendium [of the Popish Plot trials] (1679) and The Earl of Castlemaine's Manifesto (1681).

Family

On 14 April 1659 he married Barbara Villiers against his family's wishes; his father predicting at the time of the wedding that she would make him one of the most miserable men in the world. Roger was a quiet, studious, bookish man and a devout Roman Catholic while his wife was an accomplished sexual athlete and a woman of whom her later lover, Charles II himself, is recorded by Pepys on 15 May 1663 as having claimed that "she hath all the tricks of Aretin that are to be practised to give pleasure".

At the time of Roger's wedding to Barbara, she was already the mistress of Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl of Chesterfield and the marriage does not appear to have prevented her from continuing this relationship nor indeed of seeking out new partners.

Within a year, Barbara became the favourite mistress or 'mistresse en titre,' of King Charles II, coincident with his restoration to the throne in May 1660. In an entry to his diary on 13 July 1660, Pepys describes "[t]he King and Dukes there with Madame Palmer, a pretty woman that they have a fancy to, to make her husband a cuckold".

On 25 February 1660 Barbara gave birth to a daughter named Lady Anne Palmer, who Palmer believed was his own daughter. Samuel Pepys in his diary on 23 August 1662 said: "But that which pleased me best was that my Lady Castlemayne stood over against us upon a piece of White-hall — where I glutted myself with looking on her. But methought it was strange to see her Lord and her upon the same place, walking up and down without taking notice one of another; only, at first entry, he put off his hat and she made him a very civil salute — but afterwards took no notice one of another. But both of them now and then would take their child, which the nurse held in her armes, and dandle it." The child was Anne. However, Charles II also acknowledged her with her sister Charlotte as "his dear and natural daughters by the Duchess of Cleveland" and described her as "the Lady Anne Fitzroy" when granting her a patent of the arms granted to her brother Charles, then Earl (later Duke) of Southampton. The Earl of Chesterfield also claimed the child as his own.

In early June 1662 Barbara had given birth to a son named Charles who it is believed was fathered by the King. Although Roger Palmer insisted on treating the boy as his and ensured that he was baptised as a Roman Catholic, Barbara snatched away the young boy and arranged for him to be re-christened in the Church of England. Other children followed, none of whom were claimed by Palmer as his own, and most of whom were subsequently acknowledged by Charles II.

References

- "Palmer, Roger (PLMR652R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- History of Parliament Online - Palmer, Roger

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 42. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 520. ISBN 0-19-861392-X.Article by R.A.P.J. Beddard.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington, The History of England from the Accession of James II, Volume II. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1878, p. 206.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington, The History of England from the Accession of James II, Volume II. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1878, p. 209.

- Baron Thomas Babington Macaulay. The History of England from the Accession of James II. / Complete Contents of the Five Volumes (Kindle Location 14422).

- "Llanfyllin". The National Gazetteer. 1868. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 43. p. 149.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 42. p. 521.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 42. p. 522.

External links

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). . Dictionary of National Biography. 43. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- An article on Roger Palmer at the Wayback Machine (archived 16 May 2004)

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by New Creation |

Earl of Castlemaine 1661–1705 |

Succeeded by Extinct |