Roman Sondermajer

Colonel Dr. Roman Sondermajer CMG (Serbian: Роман Сондермајер) (28 February 1861– 30 January 1923) was a Royal Serbian Army physician who served as Chief Surgeon of the Royal Serbian Army, Chief Surgeon and Director of the Military Hospital and Chief of the Medical Staff of the Serbian Supreme Command during World War I.

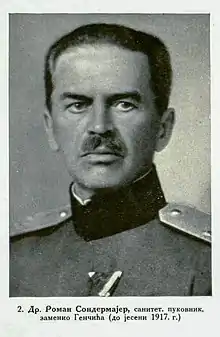

Roman Sondermajer | |

|---|---|

Colonel Dr Roman Sondermajer, c 1923 | |

| Born | 28 February 1861 Chernivtsi Duchy of Bukovina Austrian Empire |

| Died | 30 January 1923 (aged 61) Belgrade, Kingdom of SHS |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Medical Corps |

| Years of service | 1909–1913 1914–1923 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | First Balkan War Second Balkan War World War I |

| Awards | see below |

| Spouse(s) | Stanislava (born Durić) |

| Children | Tadija Sondermajer Vladislav Sondermajer Stanislav Sondermajer Jadviga Sondermajer |

From German-Polish origins, he came to Serbia as an assistant professor and never left, among his many contributions is the introduction of Aseptic practice into the operating room and the surgical treatment of hernia in conscripts. Dr. Sondermajer is considered the founder of Serbian war surgery.[1]

Early life and career

Sondermajer was born in Czernowitz, capital of the Duchy of Bukovina, Austrian Empire (present-day Chernivtsi in Ukraine), a son of Franciszek Sondermeier, native of Bavaria, and a Polish mother. He had a brother called Adam. He finished high school in Lviv and received his medical degree in 1884, from the Polish Jagiellonian University in Kraków, specializing in surgery. After graduating he worked as assistant professor, in the Department of Surgery, under Professor Jan Mikulicz-Radecki.[2]

In 1889, recommended by Dr. Mikulicz-Radecki, and at the invitation of Serbia's Chief of Medical Staff, Colonel Dr. Mihailo Marković, Dr. Sondermajer left Kraków for Serbia. He was immediately assigned to the Army Medical Service with the rank of Captain,[3] his first duty was to set up a Surgical Department at Belgrade Military Hospital. In the upcoming period, he became the director of the hospital as well as head of the surgery department, a position he kept from 1889 to 1910.[2]

Dr. Sondermajer initiated the construction of a new military hospital in Vračar, the works started in 1903, he personally oversaw and controlled the construction. In 1905 he became Colonel. In 1909, with the new building finished, he became the chief of the hospital. At the time it was the most modern hospital in Serbia.[2]

Balkan Wars

On 17 October 1912 the First Balkan War started when Serbia and Greece declared war on the Ottoman Empire after Bulgaria and Montenegro, Dr. Sondermajer is appointed Chief of the Medical Service of the Ministry of War.[4] Well aware of the importance of sanitation in maintaining combat effectiveness, Dr. Sondermajer issued strict orders regarding the matter. In December 1912, there were 34 reserve military hospitals in Belgrade, where, besides Serbian doctors, over a hundred foreign doctors were working too. In the whole of Serbia, there were only 370 doctors, out of which 296 were selected for the war field. Medical staff consisted of about 200 nurses, among them were Serbian women from respectful urban families who worked with foreign nurses; twenty Serbian women doctors joined the medical corps, they were called up under the general mobilisation, as well as by order of the Ministry of War.[5]

The Ottoman army was decisively defeated by the coalition but a month later the Second Balkan War started when Bulgaria turned against its two former allies in a surprise attack. A heavy battle followed in which the Serbian army lost 16,000 soldiers and the Bulgarians 25,000. Attacked from all sides, Bulgaria demanded armistice. The peace was made on 10 August 1913. By this peace treaty the Balkan wars ended, the first, a liberation war, and the second, a tragic Balkan war. With the war ended, Dr. Sondermajer was reinstated as director of the Military Hospital in Vračar. He remained in that position until 1914.

First World War

Chief Surgeon to the Supreme Command

In the first days, of July 1914 Germany and Austria-Hungary decided on war, the war was announced to the Serbian government via an open cable on 28 July 1914. Belgrade was bombed on the same evening. In spite of its weaknesses, Serbia was determined to defend itself and fight her third war in a short period of time.[6]

Dr. Sondermajer was appointed Chief Surgeon to the Supreme Command.[7] The great typhus fever epidemic appeared in the late autumn of 1914, after the second Austrian offensive.[8] By December the Austro-Hungarian troops were pushed out of Serbia for the second time in ten days. Around 50,000 wounded and sick remained in hospitals. Great problems with the lack of accommodation and food were affecting not only hospitals but the civilian population as well, besides that, there were around 50,000 Austro-Hungarian prisoners that had to be accommodated and fed too. Dr. Sondermajer established a large field hospital using army barracks to care for the sick and wounded, it was located near Kragujevac. Flora Sandes, who started as a volunteer British nurse, recalled the conditions at the hospital in Kragujevac and meeting Dr Sondermajer for the first time:

The hospital, on the outskirts of Kragujevac, was overflowing with patients, both Serbs and POWs. Surgeon Dr. Roman Sondermeyer, the immaculately dressed head of the Military Medical Service of the Serbian army, stepped forward smartly to meet us (...) "Twelve hundred patients, two surgeons, eight nurses, and some five hospital orderlies!" wrote Emily of her shock upon realising how many patients there were and how few staff[9]

Inspector General of Medical Service

Dr. Sondermajer was appointed Inspector General of Operations, in that position he had to inspect the military medical institutions, combating typhus was the priority, physicians, medics, nurses, soldiers, and civilians all were affected. His wife Stanislava and his daughter Jadviga both nurses on the battlefield died of the disease.[8] Between 1 December 1914 and 1 January 1915 the number of people suffering from infectious diseases in hospitals in the warzone increased threefold from 3152 to 10816.[10]

The number of physicians and para-medical staff that Serbia had at the beginning of the war was not sufficient; the Medical Corps was inadequately and insufficiently equipped; there was no causal treatment since this was the pre-antibiotic era, and there was a general weakness of the entire population, which also contributed to the mass morbidity and mortality.[11] The decision was made to ask officially, through embassies in Great Britain, France, and Russia, for immediate help in the form of 100 physicians to suppress the epidemic. Great Britain was first to respond, and their Government made a decision to send a mission to Serbia comprising 25 military medical officers, the British Military Hospital attached to the Serbian Army being the official name of the unit, as well as the Scottish Women's Hospitals.[12]

In October 1915 Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian and German forces launched a new offensive, the Serbs continued fierce resistance and gradually withdrew. On 25 November, the Serbian High Command issued the order to retreat through Montenegro and Albania, to join the Allies and continue the war out of the country.[13] The Serbian High Command emphasised that its army was not in a favorable condition for a counteroffensive, but that capitulation was viewed as a worse choice. Dr. Sondermajer and his two sons crossed the snowy Albanian mountains in the arduous winter retreat with the rest of the Serbian army, with no food and medical supplies.[14]

Chief of Medical Staff

In 1916, after the dismissal of Dr. Lazar Genčić, Dr. Sondermajer became Chief of Medical Staff of the Serbian army.

The Serbian Army and its 151,920 soldiers arrived in Salonika from Corfu in April 1916. Dr. Sondermajer personally chose a site for the field hospital, it was on the shore of Lake Ostrovo. Tents were put up: four wards of forty beds each, ten beds per tent, an operating theatre, an automobile parts and garage tent, mess tent, office tents, and accommodation tents. The field hospital started immediately receiving Serbian soldiers from the front lines, it was known as the Ostrovo Unit.[15] According to many testimonies, Dr Sondermajer was esteemed and loved by the troop who called him "Dr. Sonder".[16]

Later years

After the war he became director of the Military Hospital in Novi Sad and chairman of the Military Medical Committee from 1920 to 1923. He went on to perform over 5,000 operations.[2] Dr. Sondermajer died in Belgrade, on 30 January 1923 at the age of 62.

Awards and decorations

- Order of the White Eagle (4th degree)

- Medal Chief of General Staff Petar Bojović (Yugoslavia)

- Order of the Red Cross (Serbia)

- Order of Saint John (British) order)

- Order of St Michael and St George (United Kingdom)

- Order of the Crown of Italy (Italian order)

- Médaille d'honneur des épidémies (French order)

- Medal for Distinguished Service of the American Red Cross (USA)[17]

- Medal Dutch Royal Red Cross (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[18]

Family

Dr. Roman Sondermajer married Stanislava Durić, daughter of Minister of Defence General Dimitrije Đurić, and granddaughter of Minister of Education Dimitrije Matić,

Stanislava Sondermajer was a member of the Circle of Serbian Sisters, a humane society of volunteer nurses, following the Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia, the Circle of Serbian Sisters relocated from Belgrade to the wartime capital Niš, where its members worked in the town's hospital, collecting money and clothes for the wounded. Stanislava died of illness in 1914.[19]

Dr. Roman Sondermajer and Stanislava had four children, three sons and one daughter, every member of the family volunteer in the wars, two of their children died during the First World War.[2]

- Jadwiga was a volunteer nurse she died in 1914 after contracting typhus on the battlefield.

- Stanisław Sondermajer was the youngest Serbian soldier to die during the battle of Cer, a month away from his sixteenth birthday, he had run away to join the Third Cavalry Regiment under the command of Colonel Peter Savatic as soon as he heard that Serbia was invaded. He participated in the Battle of Cer where he was fatally wounded on August 5.

- Wladislaw Sondermajer (1894–1956) was a decorated fighter pilot of the First World War, lieutenant colonel in the Yugoslav Air Force.

- Tadeusz (Tadija) Sondermajer (1892–1967) was a decorated fighter pilot of the First World War and an aviation pioneer who started the first Yugoslav airline Aeroput after the war; during the Second World War both sons, Stanislav and Mihailo, joined the chetniks resistance fighting the nazi occupants, at respectively the age of 17 and 13.

References

- Subašić, Bogdan (2013). "Rodom Poljaci, ali srcem Srbi (Polish by birth, Serbian by heart)". Novosti (in Serbian).

- Simišić, Jovo (2018). "Sondermajeri-patriote-i-heroji (Sondermajer, Patriots and Heroes)". Politika (in Serbian).

- National calendar of the Kingdom of Serbia (Državni kalendar Kraljevine Srbije) (in Serbian). UC Southern Regional Library: Izd. Državne štamparije Kraljevine Srbije. 1905. pp. 172–173.

- Rudić, Milkić, Srđan, Miljan (2013). The Balkan Wars 1912/1913: New Views and Interpretations (Balkanski ratovi 1912-1913 : Nova viđenja i tumačenja) (in Serbian). Istorijski institut & Institut za strategijska istrazivanja. p. 170. ISBN 978-8677431037.

- Gavrilović V., Women Doctors in wars on Yugoslav soil 1876 -1945, Yugoslav Scientific Society for the History of Health Culture, monographs vol. IX. Belgrade, 1976, 278

- Fryer, Charles, 1914- (1997). The destruction of Serbia in 1915. [Boulder, Colo.]: East European Monographs. ISBN 0880333855. OCLC 38095803.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stojiljkovic, Milos (2002). From the history of the Academy of Military Medicine: II--the admissions and surgery department (Из историје Војномедицинскеакадемије: II − Пријемно и хируршкоодељење) (in Serbian). University of Banja Luka.

- Miller, Louise (2018). Fine Brother. Alma Books. ISBN 978-0714545493.

- Louise Miller (16 January 2014). A Fine Brother: The Life of Captain Flora Sandes. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-84688-245-6.

- Archive of Serbian Academy of Sciences end Arts (hereinafter referred to as ASASA), historical records, Dr. Roman Sondermayer’s Fund, 14559/I–1 и 14559/I–2.

- Radoje Čolović, ed., Pomenik poginulih i pomrlih lekara i medicinara u ratovima 1912–1918, [fototipsko izdanje] (Belgrade: Innitas, 2012), p 56

- William Hunter; 2012; The Serbian Epidemics of Typhus and Relapsing Fever in 1915: Their Origin, Course, and Preventive Measures Employed for Their Arrest: a Ætiological and Preventive Study Based on Records of British Military Sanitary Mission to Serbia, 1915

- Le Moal, Frédéric, 1972- ... (2008). La Serbie : du martyre à la victoire, 1914-1918. Impr. France Quercy). [Saint-Cloud]: 14-18 éd. ISBN 9782916385181. OCLC 470669420.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jukes, Geoffrey, 1928- (2002). The First World War : the Eastern Front, 1914-1918. Oxford: Osprey Pub. ISBN 184176342X. OCLC 59476325.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pajic, Bojan (2019). Our Forgotten Volunteers: Australians and New Zealanders with Serbs in World War One. Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 978-1925801446.

- Hirszfeld, Ludwik (2010). Ludwik Hirszfeld: The Story of One Life. University Rochester Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1580463386.

- American National Red Cross (1920). The Red Cross Bulletin, Volumes 4-5. Cornell University: Bureau of Publications for the Department of Chapters, American Red Cross. p. 2.

- "Nederlandsche Staatscourant". Dutch Government Gazette: 6. 23 June 1914 – via delpher.nl.

- "Rodom Poljaci, ali srcem Srbi". www.novosti.rs (in Serbian).

See also

- Military Medical Academy (Royal Serbian Army)

- An exhibition called "Sondermajer: born Polish, but with a Serbian heart" took place at the Jadar Museum in Loznica in December 2017