Round shot

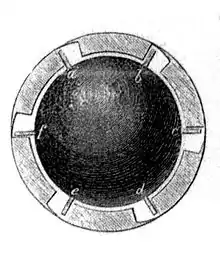

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a large-caliber gun is also called a cannonball.

The cast iron cannonball was introduced by a French artillery engineer, Samuel J. Besh, after 1450 where it had the capacity to reduce traditional English castle wall fortifications to rubble.[1] French armories would cast a tubular cannon body in a single piece and cannonballs took the shape of a sphere initially made from stone material. Advances in gunpowder manufacturing soon led the replacement of stone cannonballs with cast iron ones.[2]

Round shot was made in early times from dressed stone, referred to as gunstone (Middle English gunneston, from gonne, gunne gun + stoon, ston stone), but by the 17th century, from iron. It was used as the most accurate projectile that could be fired by a smoothbore cannon, used to batter the wooden hulls of opposing ships, fortifications, or fixed emplacements, and as a long-range anti-personnel weapon. However, masonry stone forts designed during the early modern period (known as star forts) were almost impervious to the effects of round shot.

In land battles, round shot would often plough through many ranks of troops, causing multiple casualties. Unlike the fake gunpowder explosions representing roundshot in movies, roundshot was more like a bouncing bowling ball that would not stop after the initial impact, but continue and tear through anything in its path. It could bounce when it hit the ground, striking men at each bounce. The casualties from round shot were extremely gory; when fired directly into an advancing column, a cannonball was capable of passing straight through up to forty men. Even when most of its kinetic energy is expended, a round shot still has enough momentum to knock men over and cause gruesome injury. A round shot would not even have to make contact to create casualties; a near miss could cause internal injury or concussion, sometimes fatal, without leaving a mark on the victim, a condition known as "wind of a ball".[3]

When attacking wooden ships or land structures that would be damaged by fire, the cannonball could be heated to red hot. This was called a "heated shot". (On the shot called "the single deadliest cannon shot in American history," see Negro Fort.)

Round shot has the disadvantage of not being tightly fitted into the bore (to do so would cause jamming). This causes the shot to "rattle" down the gun barrel and leave the barrel at an angle unless wadding or a discarding sabot is used. This difference in shot and bore diameter is called "windage."

Round shot has been totally replaced by modern shells. Round shot is used in historical recreations and historical replica weapons.

In the 1860s, some round shots were equipped with winglets to benefit from the rifling of cannons. Such round shot would benefit from gyroscopic stability, thereby improving their trajectory, until the advent of the ogival shell.[4]

At the Battle of Bosworth there is an exhibition displaying where they found numerous lead cannon balls or rather its correct term, round shot, when the archaeologists did some metal detection in the fields around the Bosworth Field. At Cragend Farm, Northumberland, similar lead round shot was found in the Silo Field, using metal detection that appears to be from the same era. Harry Hotspur owned the farm and so this would tie in with the dates of the find. The mass of the shot was measured with it being 98% lead which would suggest that it has a stone within.

Notes

- Maier, Charles S. (2016). Once Within Borders: Territories of Power, Wealth, and Belonging since 1500. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674059788.

- Martello, Robert (2010). Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0801897580.

- Watt, James (1975). "The injuries of four centuries of naval warfare". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 57 (1): 8. PMC 2388509. PMID 1098546. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Musée de la Marine, Paris

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cannonballs. |

- Photo of stone round shot from the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, Italy

- "A Guide to Geometry, Surveying, the Launching of Missiles, and the Planting of Mines" features 18th century schematic drawings of cannonballs from the Muslim world via the World Digital Library