Rumbula massacre

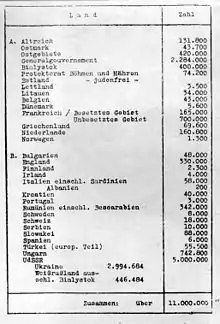

The Rumbula massacre is a collective term for incidents on November 30 and December 8, 1941, in which about 25,000 Jews were killed in or on the way to Rumbula forest near Riga, Latvia, during the Holocaust. Except for the Babi Yar massacre in Ukraine, this was the biggest two-day Holocaust atrocity until the operation of the death camps.[1] About 24,000 of the victims were Latvian Jews from the Riga Ghetto and approximately 1,000 were German Jews transported to the forest by train. The Rumbula massacre was carried out by the Nazi Einsatzgruppe A with the help of local collaborators of the Arajs Kommando, with support from other such Latvian auxiliaries. In charge of the operation was Höherer SS und Polizeiführer Friedrich Jeckeln, who had previously overseen similar massacres in Ukraine. Rudolf Lange, who later participated in the Wannsee Conference, also took part in organizing the massacre. Some of the accusations against Latvian Herberts Cukurs are related to the clearing of the Riga Ghetto by the Arajs Kommando. The Rumbula killings, together with many others, formed the basis of the post-World War II Einsatzgruppen trial where a number of Einsatzgruppen commanders were found guilty of crimes against humanity.[2]

| Rumbula massacre | |

|---|---|

Remembrance stone, placed in 1964 by Jewish activists in memory of those killed in the massacre. | |

| Also known as | Rumbula, Rumbuli, Rumbula Action, the Big Action, the Jeckeln Action |

| Location | Rumbula forest, near Riga, Latvia, Reichskommissariat Ostland |

| Date | November 30 and December 8, 1941 |

| Incident type | Genocide, Mass shootings |

| Perpetrators | Friedrich Jeckeln, Rudolf Lange, Roberts Osis, Eduard Strauch, and others |

| Participants | Viktors Arājs, Herberts Cukurs, and others |

| Organizations | Einsatzgruppen, Ordnungspolizei, Arajs Kommando, Latvian Auxiliary Police and (possibly) Wehrmacht |

| Ghetto | Riga ghetto |

| Victims | About 24,000 Latvian Jews and 1,000 German Jews. |

| Witnesses | Hinrich Lohse, Otto Drechsler, and others |

| Memorials | On site |

Nomenclature

This massacre is known by different names, including "The Big Action", and the "Rumbula Action", but in Latvia it is just called "Rumbula" or "Rumbuli".[3] It is sometimes called the Jeckeln Action after its commander Friedrich Jeckeln.[4] The word "Aktion", which translates literally to action or operation in English, was used by the Nazis as a euphemism for murder.[5] For Rumbula, the official euphemism was "shooting action" (Erschiessungsaktion).[6] In the Einsatzgruppen trial before the Nuremberg Military Tribunal, the event was not given a name but simply described as "the murder of 10,600 Jews" on 30 November 1941.[2]

Location

Rumbula was a small railroad station 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) south of Riga, the capital and major city of Latvia, which was connected with Daugavpils, the second largest city in Latvia, by the rail line along the north side of the Daugava river.[7] Located on a hill about 250 meters (820 ft) from the station, the massacre site was a "rather open and accessible place".[8] The view was blocked by vegetation, but the sound of gunfire would have been audible from the station grounds. The area lay between the rail line and the Riga-Daugavpils highway, with the rail line to the north of the highway.[7] Rumbula was part of a forest and swamp area known in Latvian as Vārnu mežs, which means Crow Forest in English.[1] The sounds of gun fire could be and were heard from the highway.[9] The German occupation authorities carried out a number of other massacres on the north bank of the Daugava in the Rumbula vicinity. The soil was sandy and it was easy to dig graves.[7] While the surrounding pine woods were sparse, there was a heavily forested area in the center which became the execution site.[7] The rail line and highway made it easy to move the victims in from Riga (it had to be within walking distance of the Riga Ghetto on the southeast side of the city), as well as transport the murderers and their arms.[3]

The Holocaust in Latvia

The Holocaust in Latvia began on June 22, 1941, when the German army invaded the Soviet Union, including the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia that had been recently occupied by Soviet forces following a period of independence after World War I. Murders of Jews, Communists, and others began almost immediately, perpetrated by German killer squads known as Einsatzgruppen (which can be translated as "Special Task Groups" or "Special Assignment Groups"), and also other organizations, including the German Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei or Sipo) and the Security Service of the SS (Sicherheitsdienst or SD). The first murders were on the night of June 23, 1941, in the town of Grobina, near Liepāja, where Sonderkommando 1a members murdered six Jews in the church cemetery.[5] The Nazi occupiers were also aided by a unit of native Latvians known as the Arājs Commando, and at least to some extent by Latvian auxiliary police.[3][11]

Involvement of local population

The Nazis wished to make it appear as if the local populations of Latvians were responsible for the murders of the Jews. They attempted, without much success,[12] to stir up local deadly riots, known as "pogroms", against the Jews. They spread rumors that Jews were responsible for widespread arson and other crimes, and even reported the same to their superiors.[13] This policy of incitement to what the Nazis called "self-cleansing actions" was acknowledged to be a failure by Franz Walter Stahlecker, who, as chief of Einsatzgruppe A, was the Nazis' main killing expert in the Baltic states.[14][15]

Creation of the Riga Ghetto

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

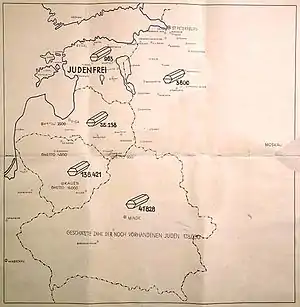

The SD's goal was to make Latvia judenrein, a Nazi neologism which can be translated as "Jew free." By October 15, 1941, the Nazis had murdered up to 30,000[13] of the approximately 66,000 Jews that had not been able to flee the country before the German occupation was completed. Hinrich Lohse, who reported to Alfred Rosenberg rather than the SD's boss, Heinrich Himmler, wanted not so much to exterminate the Jews but rather to steal all their property, confine them to ghettos,[16] and use them as slave laborers for Germany's war effort. This bureaucratic conflict slowed down the pace of killing in September and October 1941. Lohse, as part of the "civil administration" was perceived by the SD as resisting their plans.[17] On November 15, 1941, Lohse asked for directions from Rosenberg as to whether all Jews were to be murdered "regardless of economic considerations."[18][19][20] By the end of October, Lohse had confined all the Jews of Riga, as well some of the surrounding area, into a ghetto within the city, the gates of which were about 10 kilometers from Rumbula.[3] The Riga Ghetto was a creation of the Nazis themselves, and had not existed before the war.[21]

Entry of Friedrich Jeckeln

Motive

Himmler's motive was to eliminate the Latvian Jews in Riga so that Jews from Germany and Austria could be deported to the Riga ghetto and housed in their place.[24] Similarly motivated mass murders of eastern Jews confined to ghettos were carried out at Kovno on October 28, 1941 (10,000 dead), and at Minsk, where 13,000 were shot on November 7 and an additional 7,000 on November 20.[25] To carry out this plan, Himmler brought Friedrich Jeckeln into Latvia from the Ukraine, where he had organized a number of mass murders, including Babi Yar (30,000 dead). Jeckeln's crew of about 50 killers and supporting personnel arrived in Riga on November 5, 1941. Jeckeln did not arrive with them, but went instead to Berlin where sometime between November 10 and November 12, 1941,[26] he met with Himmler. Himmler told Jeckeln to kill the entire Riga ghetto and to instruct Lohse, should he object that this was an order of Himmler's and also of Adolf Hitler's: "Tell Lohse it is my order, which is also the Führer's wish".[27]

Jeckeln then went to Riga and explained the situation to Lohse, who raised no further objection. By mid-November 1941, Jeckeln had set himself up in a building in the old section of Riga known as the Ritterhaus.[28] Back in Berlin, Rosenberg, Lohse's superior in the Nazi hierarchy, was able to get one concession out of Himmler, that slave labor extracted from male Jews aged 16–60 would be considered too important to Germany's war effort. Consequently, these people would be spared, while women, children, old and disabled people would be shot. Jeckeln's plan for carrying out this segregation of the victims came to be known as the "Little Ghetto".[3]

Planning the massacre

To fulfill Himmler's order to clear out the Ghetto, Jeckeln would need to kill 12,000 people per day. At that time of year, there were only about eight hours of day and twilight, so, the last column of victims would have to leave the Riga ghetto no later than 12:00 noon. Guards would be posted on both sides along the entire 10 kilometer column route. The whole process required about 1,700 personnel to carry it out.[29]

Jeckeln's construction specialist, Ernst Hennicker, who later claimed he was shocked when he learned in advance of the number of people to be murdered, nevertheless made no objection at the time and proceeded to supervise the digging of six murder pits, sufficient to bury 25,000 people.[30][29] The actual excavation of the pits was done by 200[3] or 300[30] Russian prisoners of war. The pits themselves were purpose-designed: they were excavated in levels, like an inverted pyramid, with the broader levels towards the top, and a ramp down to the different levels to allow the victims to be literally marched into their own graves. It took about three days to finish the pits which were complete by November 23, 1941.[29]

The actual shooting was done by 10 or 12 men of Jeckeln's bodyguard, including Endl, Lueschen, and Wedekind, all experienced murderers. Much later, Jeckeln's driver, Johannes Zingler, claimed in testimony that Jeckeln had forced him to join in as a killer by making threats to harm Zingler's family.[29] In similar massacres in Russia and the Ukraine, there were many accounts contrary to Zingler's to the effect that participation was voluntary, and even sometimes sought after, and that those who refused to take part in shootings suffered no adverse consequences.[31] In particular, Erwin Schulz, head of Einsatzkommando 5, refused to participate in Babi Yar, another Jeckeln atrocity, and at his own request was transferred back to his pre-war position in Berlin with no loss of professional standing.[31]

Jeckeln had no Latvians carrying out shootings. Jeckeln considered the shooting of the victims in the pits to be a deed of marksmanship, and he wanted to prove Germans were inherently more accurate shooters than Latvians. Jeckeln also didn't trust other agencies, even Nazi ones, to carry out his wishes. Although the SD and the Order Police were involved, Jeckeln assigned his own squad to supervise every aspect of the operation.[29]

Deciding on the site

Jeckeln and his aide Paul Degenhart searched the Riga vicinity to find a site. Riga was located in a swampy area where the water table was close to ground level. This would interfere with the proper disposal of thousands of corpses. Jeckeln needed elevated ground. The site also had to be on the north side of the Daugava River within walking distance of the ghetto, also on the north side. On or about November 18 or 19[29] Jeckeln came upon Rumbula as he was driving south to the Salaspils concentration camp (then under construction), and it fit what he was looking for. The site was close to Riga, it was on elevated ground, and it had sandy soil, with the only drawback being the proximity to the highway (about 100 meters).[29]

Jeckeln system

Jeckeln developed his "Jeckeln system" during the many murders he had organized in the Ukraine, which included among others Babi Yar and the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre.[32] He called it "sardine packing" (Sardinenpackung).[33] The Jeckeln method was noted, although not by name, in the judgment of the Einsatzgruppen commanders at Nuremberg Military Tribunal, as a means of avoiding the extra work associated with having to push the bodies into the grave.[34] It was reported that even some of the experienced Einsatzgruppen killers claimed to have been horrified by its cruelty.[32] Extermination by shooting ran into a problem when it came to women and children.[35] Otto Ohlendorf, himself a prolific killer, objected to Jeckeln's techniques according to his testimony at his post-war trial for crimes against humanity.[36] Jeckeln had staff which specialized in each separate part of the process, including Genickschußspezialisten -- "neck shot specialists".[37] There were nine components to this assembly-line method as applied to the Riga ghetto.

- The Security Police roused the people out of their houses in the ghetto;

- The Jews were organized into columns of 1000 people and marched to the killing grounds;

- The German Order Police (Ordnungspolizei or Orpo) led the columns to Rumbula;

- Three pits had already been dug where the killing would be done simultaneously;

- The victims were stripped of their clothing and valuables;

- The victims were run through a double cordon of guards on the way to the killing pits;

- To save the trouble of tossing dead bodies into the pits, the killers forced the living victims into the trench on top of other people who had already been shot;

- Russian submachine guns (another source says semi-automatic pistols[7]) were used rather than German arms, because the magazine held 50 rounds and the weapon could be set to fire one round at a time. This also allowed some deniability because should the bodies be discovered, the claim could be made that since the victims had been shot with Russian bullets, the NKVD or some other Communist organization was responsible.

- The killers forced the victims to lie face down on the trench floor, or more often, on the bodies of the people who had just been shot. The people were not sprayed with bullets. Rather, to save ammunition, each person was shot just once, in the back of the head. Anyone not murdered outright was simply buried alive when the pit was covered up.[38]

Arranging transport for infirm victims

Jeckeln had at his direct disposal 10 to 12 automobiles and 6 to 8 motorcycles. This was enough to transport the killers themselves and certain official witnesses. Jeckeln needed more and heavier transport for the sick, disabled or other of his intended victims who could not make the 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) march. Jeckeln also anticipated there would be a significant number of people murdered along the march route, and he would need about 25 trucks to pick up the bodies. Consequently, he ordered his men to scrounge through Riga to locate suitable vehicles.[39]

Final planning and instructions

On or about Thursday, November 27, 1941, Jeckeln held a meeting of the leaders of the participating units at the Riga office of the Protective Police (Schutzpolizei), a branch of the German Order Police, (Ordnungspolizei) to coordinate their actions in the forthcoming massacre. This appears consistent with the substantial role that the Order Police played in the Holocaust, as stated by Professor Browning:

It is no longer seriously in question that members of the German Order Police, both career professionals and reservists, in both battalion formations and precinct service or Einzeldienst, were at the center of the Holocaust, providing a major manpower source for carrying out numerous deportations, ghetto-clearing operations, and massacres.

— Christopher Browning[40]

Jeckeln convened a second planning session of senior commanders on the afternoon of Saturday, November 29, 1941, this time at the Ritterhaus. According to later versions given by those in attendance, Jeckeln gave a speech to these officers to the effect that it was their patriotic duty to exterminate the Jews of the Riga ghetto, just as much as if they were on the front lines of the battles then currently raging far to the east. Officers also later claimed that Jeckeln told them that failure to participate in the murders would be considered the equivalent of desertion, and that all HSSPF personnel who would not be participating in the action were required to attend the extermination site as official witnesses. No Latvian officials were present at the November 29 Ritterhaus meeting.[41]

At about 7:00 p.m. on November 29, a brief (about 15 minutes) third meeting was held, this time at the Protective Police headquarters. This was presided over by Karl Heise, the head of the protective police. He told his men they would have to report the next morning at 4:00 a.m. to carry out a "resettlement" of the people in the Riga ghetto. Although "resettlement" was a Nazi euphemism for mass murder, Heisse and a majority of men of the participating Protective Police knew the true nature of the action. Final instructions were also passed to the Latvian militia and police who would be rounding up people in the ghetto and acting as guards along the way. The Latvian police were told they would be moving the Jews to the Rumbula station for transport to a resettlement camp.[41]

In the Jahnke trial in the early 1970s, the West German court in Hamburg found that a purpose of the Jeckeln system was to conceal the murderous purpose until the very last.[42] The court further found:

- That by the evening meeting on November 29, 1941, the intermediate commanders knew the full extent of the intended murders;

- That the intermediate commanders also knew that the 20 kilogram luggage rule was a ruse to deceive the victims into a belief that they were truly being resettled;[7]

- That the men in the lower ranks did not know what was planned until they saw the shootings in the forest.[42]

Professor Ezergailis questioned whether the Latvian police might have had a better idea of what was actually going to happen, this being their native country, but he also noted contrary evidence including misleading instructions given to the Latvian police by the Germans, and the giving of instructions, at least to some Germans, to shoot any guard who might fail to execute a "disobedient" Jew during the course of the march.[42]

Advance knowledge by Wehrmacht

According to his later testimony before the Nuremberg Military Tribunal at the High Command Trial, Walter Bruns, a Major General of Engineers, learned on November 28 that planned mass executions would soon take place in Riga.[43] Bruns sent a report to his superiors, then urged a certain "administrative officer", named Walter Altemeyer to postpone the action until Bruns could receive a response. Altemeyer told Bruns that the operation was being carried out pursuant to a "Führer-order".[43] Bruns then sent out two officers to observe and report.[43][44] Advance word of the planned murders reached the Wehrmacht intelligence office ("Abwehr") in Riga.[45] This office, which was not connected with the massacre, had received a cable shortly before the executions began, from Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, which in summary instructed the Riga Abwehr that "it is unworthy of an intelligence officer to be party to, or even present at interrogations or maltreatments".[45] By "interrogations and maltreatments", Canaris was referring to the planned massacre.[45]

Preparation for the massacre

Able-bodied men separated from the others

On about November 27, 1941 a four-block area of the Riga ghetto was cordoned off with barbed wire, and this area became known as the "small ghetto".[16] On November 28, the Nazis issued an order requiring the able-bodied men to move to the small ghetto and the rest of the population was to report at 6:00 a.m. on November 30 to a different area for "light work" with no more than a 20-kilogram (44 lb) bag. The reaction among the Jews was one of horror.[46] In July and August, it was the men of Latvia who were shot first, while the women and children were allowed to live, at least for a time. The order for the men to separate themselves from their families was thus perceived as a predicate for the murder of the men, the arrangements between Rosenberg and Himmler having been made without their knowledge. By the morning of Saturday, November 29, the Nazis had finished segregating the able-bodied men into the small ghetto.[47]

Ghetto survivor Max Kaufmann described the scene somewhat differently, writing that on Thursday morning, November 27, a large poster was put up on Sadornika Street in the ghetto, which said, among other things, that on Saturday, November 29, 1941, all inmates of the ghetto were to form up in columns of 1,000 people each near the ghetto gate for evacuation from the ghetto. The people living closest to the gate would be the first to depart.[48] Kaufmann doesn't describe a specific order separating the able-bodied men from the rest of the people. Instead he states that "the larger work crews were told they had the possibility of staying in the newly formed small camp and rejoining their families later.[48] According to Kaufmann, while the columns of 1,000 were formed on the morning of the 29th, they were later dispersed, causing relief among the inhabitants, who believed that the entire evacuation had been cancelled. 300 women seamstresses were also selected and moved to the Central Prison from the ghetto.[48]

Professor Ezergailis states that while the men were at work, the Nazis culled the able-bodied men from those left in the ghetto, and once the work crews returned, the same process was employed again on the returning workers. The total, about 4,000 able-bodied men, were sent to the newly created small ghetto.[47] Kaufmann states that after returning from work on the 29th, he and his son, then aged 16, would not return to the large ghetto, but were housed instead in a ruined building on Vilanu Street in the small ghetto.[48]

First transport of German Jews arrives in Riga

The first transport of German Jews to Riga departed Berlin on Thursday, November 27, 1941[49] and arrived in Riga on Saturday, November 29, 1941. Whether the Jews were to be worked and starved to death over time, or simply murdered outright had not yet been decided upon.[19] Apparently at the last minute, Himmler decided he did not want these German Jews murdered immediately; his plan instead was to house them in the Riga Ghetto in the dwellings to be made available from the murder of the Latvian Jews.[49]

For this reason, on Sunday, November 30, 1941, Himmler placed a telephone call to Reinhard Heydrich,[50] who, as head of the SD was also Jeckeln's boss. According to Himmler's telephone log, his order to Heydrich was that the Jews on the transport from Berlin were not to be murdered, or in the Nazi terminology, "liquidated" (Judentransport aus Berlin. Keine Liquidierung).[50] Himmler however only made this call at 1:30 in the afternoon that Sunday, and by that time, the people on the train were dead.[49] What had happened was that there was no housing for the deported German Jews when they arrived in Riga, so the Nazis left them on the train. The next morning, the Nazis ran the trainload of people down to the Rumbula station. They took the people off the train, marched them the short distance to the crime scene and shot them all between 8:15 and 9:00 a.m.[7] They were the first group to die that day.[3] The Nazi euphemism for this crime was that the 1,000 Berlin Jews had been "disposed of."[51] Thereafter, on December 1, and, in a personal conference on December 4, 1941, Himmler issued strict instructions to Jeckeln that no mass murders of deported German Jews were to occur without his express orders:[49] "The Jews deported into the territory of the Ostland are to be dealt with only according to the guideline given by me and the Reich Security Main Office acting on my behalf. I will punish unilateral acts and violations."[52]

Jeckeln claimed at his post-war trial that he'd received orders from Himmler on November 10 or 11, that "all the Jews in the Ostland down to the last man must be exterminated."[19] Jeckeln might well have believed that killing the German Jews on the Riga transport was what Himmler wished, for just before the Rumbula massacre, mass murders of German Jews upon or shortly after arrival in the East had been carried out in Kaunas, Lithuania, on November 25 and 29, 1941, when the Sipo murdered 5,000 German and Austrian Jews who had arrived on transports on November 11, including some 1,000 Jews from Berlin.[53]

Professor Fleming suggests several reasons for Himmler's "no liquidation" order. On board the train were 40 to 45 people who were considered "cases of unjustified evacuation", meaning they were either elderly or had been awarded the Iron Cross for heroic service to Germany during the Great War. Another reason may have been that Himmler hesitated to carry out the execution of German Jews for fear of the effect that it might have on the attitude of the United States, which as of November 30, 1941, was not yet at war with Germany.[27] Professor Browning attributes the order and the fact that, with two significant exceptions, in general further transports of Jews to Riga from Germany did not result in immediate mass execution, to Himmler's concern over some of the issues raised by the shooting of German (as opposed to native) Jews and the desire to postpone the same until it could be in greater secrecy and at a time when less controversy might arise among the Nazis themselves.[54]

Women, children and elderly forced out of ghetto

When the columns were dispersed on Saturday, November 29, the ghetto inhabitants believed, to their relief, that there would be no evacuation.[48] This proved wrong. The first action in the ghetto began at 4:00 a.m., well before dawn, on Sunday, November 30, 1941. Working from west to east (that is, towards Rumbula), squads of the SD, the Protective Police, the Araji commando, and about 80 Jewish ghetto police rousted people from their sleep and told them to report for assembly in half an hour.[16] Max Kaufmann describes the raid as beginning in the middle of the night on the 29th.[55] He describes "thousands" of "absolutely drunk" Germans and Latvians invading the ghettos, bursting into apartments, and hunting down the occupants while shouting wildly. He states that children were thrown from third floor windows.[55] Detachments cut special openings in the fence to allow more rapid access to the highway south to the forest site. (Detailed maps of the ghetto are provided by Ezergailis[56] and Kaufmann.)

Even though the able-bodied men were gone, people still resisted being forced out of their dwellings and tried to desert from the columns as they moved through the eastern part of the ghetto. The Germans murdered 600 to 1,000 people in the process of forcing out the people. Eventually columns of about 1,000 people were formed and marched out. The first column was led by the lawyer, Dr. Eljaschow. "The expression on his face showed no disquiet whatsoever; on the contrary, because everyone was looking at him, he made an effort to smile hopefully."[57] Next to Dr. Eljaschow was Rabbi Zack. Other well-known citizens of Riga were in the columns.[57] Among the guards were Altmeyer, Jäger, and Herberts Cukurs. Cukurs, a world-famous pilot, was the most recognizable Latvian SD man at the scene,[58] whom Kaufmann described as follows:

The Latvian murderer Cukurs got out of a car wearing a pistol (Nagant) in a leather holster at his side. He went to the Latvian guards to give them various instructions. He had certainly been informed in detail about the great catastrophe that awaited us.

— Churbn Lettland - The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia[55]

Latvian historian Andrew Ezergailis states that "although Arajs' men were not the only ones on the ghetto end of the operation, to the degree they participated in the atrocities there the chief responsibility rests on Herberts Cukurs' shoulders."[59]

The Jews were allowed to carry some luggage as a sham, to create the impression among the victims that they were simply being resettled.[7] Frida Michelson, one of the few survivors of the massacre at the pits, later described what she saw that day:

It was already beginning to get light. An unending column of people, guarded by armed policemen, was passing by. Young women, women with infants in their arms, old women, handicapped helped by their neighbors, young boys and girls -- all marching, marching. Suddenly, in front of our window, a German SS man started firing with an automatic gun point blank into the crowd. People were mowed down by the shots, and fell on the cobblestones. There was confusion in the column. People were trampling over those who had fallen, they were pushing forward, away from the wildly shooting SS man. Some were throwing away their packs so they could run faster. The Latvian policemen were shouting 'Faster, faster' and lashing whips over the heads of the crowd.

... The columns of people were moving on and on, sometimes at a half run, marching, trotting, without end. There one, there another, would fall and they would walk right over them, constantly being urged on by the policemen, 'Faster, faster', with their whips and rifle butts.

... I stood by the window and watched until about midday when the horror of the march ended ... . Now the street was quiet, nothing moved. Corpses were scattered all over, rivulets of blood still oozing from the lifeless bodies. They were mostly old people, pregnant women, children, handicapped -- all those who could not keep up with the inhuman tempo of the march.— Frida Michelson, I Survived Rumbuli, pp. 77-8

Ten kilometer march to the killing pits

The first column of people, accompanied by about 50 guards, left the ghetto at 06:00 hours. On November 30, 1941, the air temperatures recorded at Riga were −7.5 °C (18.5 °F) at 07:00 hours, −1.1 °C (30.0 °F) at 09:00, and 1.9 °C (35.4 °F) at 21:00. The previous evening there had been a snowfall of 7 cm (2.8 in), but no snow fell on November 30 from 07:00 to 21:00.[7] The people could not keep up the pace demanded by the guards and the column kept stretching out. The guards murdered anyone who fell out of the column or stopped to rest along the 10-kilometer (6.2 mi)[60] march route. German guards, when later tried for war crimes, claimed it was the Latvians who did most of the killing. In Latvia, however, there were stories about Latvian policemen refusing orders to shoot people.[61]

Arrival at Rumbula and murder

The first column of people arrived at Rumbula at about 9:00 am on November 30. The people were ordered to disrobe and deposit their clothing and valuables in designated locations and collection boxes, shoes in one, overcoats in another, and so forth.[7] Luggage was deposited before the Jews entered the wood.[7] They were then marched towards the murder pits. If there were too many people arriving to be readily murdered immediately, they were held in the nearby forest until their turn came. As the piles of clothing became huge, members of the Arajs Commando loaded the articles on trucks to be transported back to Riga. The disrobing point was watched carefully by the killers, because it was here that there was a pause in the conveyor-like system, where resistance or rebellion might arise.[3][7]

The people were then marched down the ramps into the pits, in single file ten at time, on top of previously shot victims, many of whom were still alive.[7][62] Some people wept, others prayed and recited the Torah. Handicapped and elderly people were helped into the pit by other sturdier victims.[7]

The victims were made to lie face down on top of those who had already been shot and were still writhing and heaving, oozing blood, stinking of brains and excrement. With their Russian automatic weapons set on single shots, the marksmen murdered the Jews from a distance of about two meters with a shot in the backs of their heads. One bullet per person was allotted in the Jeckeln system.

— Andrew Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941-1944: The Missing Center, pp. 253–4

The shooting continued past sundown into the twilight, probably ending at about 5:00 p.m., when darkness fell. (The evidence is in conflict about when the shooting ended.[63] One source says the shooting went on well into the evening.[7]) Their aim may have been worsened by the twilight, as German police Major Karl Heise, who had gone back and forth between Riga and the killing site that day, suffered the misfortune of having been hit in the eye by a ricochet bullet.[3] Jeckeln himself described Rumbula at his trial in early 1946.

Q: Who did the shooting?

A: Ten or twelve German SD soldiers.

Q: What was the procedure?

A: All of the Jews went by foot from the ghetto in Riga to the liquidation site. Near the pits, they had to deposit their overclothes, which were washed, sorted, and shipped back to Germany. Jews - men, women, and children - passed through police cordons on their way to the pits, where they were shot by German soldiers.— Jeckeln interrogation excerpts[64]

The shooters fired from the brink of the smaller pits. For the larger pits, they walked down in the graves among the dead and dying to shoot additional victims.[7] Captain Otto Schulz-Du Bois, of the Engineer Reserves of the German Army, was in the area on bridge and road inspection duties, when he heard "intermittent but persistent reports of gunfire".[65] Schulz-Du Bois stopped to investigate, and because security was weak, was able to observe the murders. A few months later he described what he saw to friends in Germany, who in 1980 reported what Schulz-Du Bois had told them:

The first thing he came upon was a huge heap of clothes, then men, women, children and elderly people standing in a line and dressed in their underclothing. The head of the line ended in a small wood by a mass gravesite. Those first in line had to leap into the pit and then were murdered with a pistol bullet in the head. Six SS men were busy with this grisly chore. The victims maintained a perfect composure. There were no outcries, only light sobbing and crying, and saying soothing words to the children.

— Gerald Fleming, Hitler and the Final Solution[65]

Official witnesses

Jeckeln required high-ranking Nazis to witness the Rumbula murders. Jeckeln himself stood at the top of the pits personally directing the shooters. National Commissioner (Reichskommissar) for the Ostland[66] Hinrich Lohse was there, at least for a while. Dr. Otto Heinrich Drechsler, the Territorial Commissioner (Gebietskommissar) of Latvia may have been present. Roberts Osis, the chief of the Latvian collaborationist militia (Schutzmannschaft) was present for much of the time. Viktors Arajs, who was drunk, worked very close to the pits supervising the Latvian men of his commando, who were guarding and funnelling the victims into the pits.[3]

Later murders and body disposal in the ghetto

Karl Heise returned from Rumbula to the Riga ghetto by about 1:00 p.m. There he discovered that about 20 Jews too sick to be moved had been taken not to the murder site but rather to the hospital. Heise ordered they be taken out of the hospital, placed on the street on straw mattresses and shot in the head. Killers of the patients in the street included members of the Schutzpolizei, Hesfer, Otto Tuchel, and Neuman, among others.[67] There were still the hundreds of bodies left from the morning's forced evacuation. A squad of able-bodied Jews was delegated to pick them up and take them to the Jewish cemetery using sleds, wheelbarrows and horse carts.[68] Not every one who had been shot down in the streets was dead; those still alive were finished off by the Arajs commando. Individual graves were not dug at the cemetery. Instead, using dynamite, the Germans blew out a large crater in the ground, into which the dead were dumped without ceremony.[3][16][69]

Aftermath at the pits on the first day

By the end of the first day about 13,000 people had been shot but not all were dead. Kaufman reported that "the earth still heaved for a long time because of the many half-dead people."[70] Wounded naked people were wandering about as late as 11:00 am the next day, seeking help but getting none. In the words of Professor Ezergailis:

The pit itself was still alive; bleeding and writhing bodies were regaining consciousness. ... Moans and whimpers could be heard well into the night. There were people who had been only slightly wounded, or not hit at all; they crawled out of the pit. Hundreds must have smothered under the weight of human flesh. Sentries were posted at the pits and a unit of Latvian Schutzmannschaften was sent out to guard the area. The orders were to liquidate all survivors on the spot.

— Andrew Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941-1944: The Missing Center, p. 255

According to historian Bernard Press, himself a survivor of the Holocaust in Latvia:

Four young women initially escaped the bullets. Naked and trembling, they stood before their murderers' gun barrels and screamed in extreme mortal agony that they were Latvians, not Jews. They were believed and taken back to the city. The next morning Jeckeln himself decided their fate. One was indeed Latvian and had been adopted as a child by Jews. The others were Jewish. One of them hoped for support from her first husband, Army Lieutenant Skuja. Asked on the telephone about her nationality, he answered that she was a Jew and he was not interested in her fate. She was murdered. The second woman received no mercy from Jeckeln, because she was the Latvian wife of a Jew engaged in Judaic studies. With this answer she signed her death warrant, for Jeckeln decided she was "tainted by Judaism." Only the third girl, Ella Medalje, was clever enough to give Jeckeln plausible answers and thus escaped with her life.

— The Murder of the Jews in Latvia, pp. 106-7

Reaction among the survivors

The ghetto itself was a scene of mass murder after the departure of the columns on November 30, as Kaufmann described:

Ludzas street in the center of the ghetto was full of murdered people. Their blood flowed in the gutters. In the houses there were also countless people who had been shot. Slowly people began to pick them up. The lawyer Wittenberg had taken this holy task upon himself, and he mobilized the remaining young people for this task.

— Churbn Lettland - The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia[70]

The blood literally ran in the gutters. Frida Michelson, an eyewitness, recorded that the next day, December 1, there were still puddles of blood in the street, frozen by then.[69]

The men in the newly created small ghetto were sent out to their work stations that Sunday, as they had been the day before. On the way, they saw the columns formed up for the march to Rumbula, and they heard weeping, screaming, and shooting, but they could learn no details. The men asked some of the German soldiers with whom they were acquainted to go to the ghetto to see what happened. These soldiers did go, but could not gain admission to the ghetto itself. From a distance, they could still see "many horrible things".[71] They reported these facts to the Jews of the work detachments, who asked them to be released early from work to see to their families. At 14:00 hours this request was granted, at least for a few of the men, and they returned to the ghetto.[71] They found the streets scattered with things, which they were directed to collect and carry to the guardhouse. They also found a small bundle which turned out to be a living child, a baby aged about four weeks. A Latvian guard took the child away. Kaufmann believed the child's murder was a certainty.[71]

December 8 murders

Jeckeln seems to have wanted to continue the murders on December 1, but did not. Professor Ezergailis proposed that Jeckeln may have been bothered by problems such as the resistance of the Jews in Riga. In any case, the killing did not resume until Monday, December 8, 1941. According to Professor Ezergailis, this time 300 Jews were murdered in forcing people out of the ghetto. (Another source reports that the brutality in the Ghetto was worse on December 8 than on November 30.[16]). It was snowing that Monday, and the people may have believed that the worst had passed.[16] Even so, the columns were formed up and marched out of the city just as on Sunday, November 30, but with some differences. The 20 kilogram packs were not carried to the site, as they had been on November 30, but were left in the ghetto. Their owners were told that their luggage would be carried on by truck to the fictitious point of departure for resettlement. Mothers with small children and older people were told they could ride by sleigh, and sleighs were in fact available.[73] At least two policemen who had played some role in the November 30 massacre refused to participate again on December 8. These were the German Zimmermann and the Latvian Vilnis.[74] The march itself was fast-paced and brutal. Many people were trampled to death.[73]

Max Kaufmann, one of the men among the work crews in the small ghetto, was anxious to know what was happening to the people marched out on December 8. He organized, through bribery, an expedition by truck ostensibly to gather wood, but actually to follow the columns and learn their destination.[75] Kaufmann later described what he saw from the truck as it moved south along the highway from Riga towards Daugavpils:

... we encountered the first evacuees. We slowed down. They were walking quite calmly, and hardly a sound was heard. The first person in the procession we met was Mrs. Pola Schmulian * * * Her head was deeply bowed and she seemed to be in despair. I also saw other acquaintances of mine among the people marching; the Latvians would occasionally beat one or another of them with truncheons. * * * On the way, I counted six murdered people who were lying with their faces in the snow.

— Churbn Lettland - The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia[75]

Kaufmann noticed machine guns set closely together in the snow near the woods, and sixty to eighty soldiers, whom he identified as being from the German army. The soldier who was driving the truck stated the machine guns were posted just to prevent escapes. (In his book, Kaufmann stated he was certain the German army had played a role in the Rumbula massacre.)[75] They drove on that day down the highway past Rumbula to the Salaspils concentration camp, to investigate a rumor that the Jews had been evacuated to that point. At the camp they encountered Russian prisoners of war, but no Jews from Riga. The prisoners told them that they knew nothing about the Jews.[75] Frida Michelson had been marched out with the column, and she described the forest as being surrounded by a ring of SS men.[73] Michelson further described the scene when they arrived at Rumbula that morning:

As we came to the forest we heard shooting again. This was the horrible portent of our future. If I had any doubts about the intentions of our tormenters, they were all gone now. ... We were all numb with terror and followed orders mechanically. We were incapable of thinking and were submitting to everything like a docile herd of cattle.

— Frida Michelson, I Survived Rumbuli, pp. 85-8

Of the 12,000 people forced out of the ghetto to Rumbula that day, three known survivors later gave accounts: Frida Michelson, Elle Madale, and Matiss Lutrins. Michelson survived by pretending to be dead as victims discarded heaps of shoes on her.[76] Elle Madale claimed to be a Latvian.[77] Matiss Lutrins, a mechanic, persuaded some Latvian truck drivers to allow him and his wife (whom the Germans later found and murdered) to hide under a truckload of clothing from the victims that was being hauled back into Riga.[77]

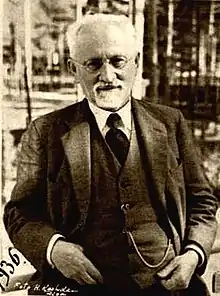

Among those slain on December 8 was Simon Dubnow, a well known Jewish writer, historian and activist. Dubnow had fled Berlin in 1933 when the Nazis took power, seeking safety in Riga.[28] On December 8, 1941, too ill to be marched to the forest, he was murdered in the ghetto.[50] and was buried in a mass grave. Kaufmann states that after November 30, Professor Dubnow was brought to live with the families of the Jewish policemen at 56 Ludzas Street. On December 8, the brutal Latvian guard overseer Alberts Danskop came to the house and asked Dubnow if he was a member of the policemen's families. Dubnow said he was not and Danskop forced him out of the house to join one of the columns that was marching past at the time. Uproar broke out in the house and one of the Jewish policemen, whom Kaufmann reports to have been a German who had won the Iron Cross, rushed out to try and save Dubnow, but it was too late.[78]

According to another account, Dubnow's killer was a German who had been a former student.[79] A rumor, which later grew into a legend,[72] stated that Dubnow said to the Jews present at the last moments of his life: "If you survive, never forget what is happening here, give evidence, write and rewrite, keep alive each word and each gesture, each cry and each tear!"[72][80] What is certain is that the SS stole the historian's library and papers and transported them back to the Reich.[81]

December 9 massacre

Some Jews who were not able-bodied working men were able to escape from the mass actions on November 30 and December 8 and hide in the new "small ghetto".[82] On December 9, 1941, the Nazis began a third massacre, this time in the small ghetto. They searched through the ghetto while the men were out at work. Whoever they found in hiding was taken out to the Biķernieki forest, on the northeast side of Riga, in blue buses borrowed from the Riga municipal authorities, where they were murdered and buried in mass graves. About 500 people were murdered in this operation. As with the Rumbula murders, evacuations from the ghetto ceased at 12 noon.[82]

Effect of Rumbula on plans for the Holocaust

German Jews replace Latvians in Riga ghetto

In December 1941, the Nazis continued issuing directions to Jews in Germany that they were to report to be deported to the East. For most of these people, because of Himmler's change of plan (as shown in his "keine Liquiderung" telephone call) they would get a year or two of life in a ghetto before their turn came to be murdered.[49][83][84] One of the first trains to arrive in Riga was called the "Bielefeld Transport."[83] Once the German Jews arrived on the Riga transports in December, 1941, they were sent to the ghetto, where they found that the houses had obviously been left in a hurry. The furnishings in the residences were in great disarray and some were stained with blood. Frozen but cooked food was on the tables, and baby carriages with bottles of frozen milk were outside in the snow.[16][50][85] On a wall a German family found the words written "Mama, farewell."[85] Years later, a German survivor, then a child, remembers being told "Latvians lived here", with no mention they were Jews.[85] Another German survivor, Ruth Foster, recounted what she had heard about the massacre:

We found out later that three days before we arrived, they murdered 30,000 Latvian Jews who came into the Ghetto from Riga and the surrounding towns. They herded them into a nearby forest where previously the Russian prisoners of war had dug graves for them, they had to undress completely, leave their clothes in neat order, and then they had to go to the edge of the pits where they were mown down with machine guns. So when we came to the Riga Ghetto, we lived in the houses where those poor people had been driven out and murdered.

— Lyn Smith, Remembering: Voices of the Holocaust, pp. 100, 114, 128.

Two months later, German Jews arriving in the ghetto were still finding bodies of murdered Latvian Jews in basements and attics.[86]

Wannsee Conference

Rudolf Lange, commander of Einsatzkommando 2 in Latvia, was invited to the infamous Wannsee Conference to give his perspective on the proposed Final Solution to the so-called Jewish question. The Nazis did not find shootings to be a feasible method of murdering millions of people, in particular because it was observed that even SS troops were uncomfortable about shooting assimilated German Jews as opposed to Ostjuden ("Eastern Jews").[35][87] The head of the German civil administration in the Baltic area, Wilhelm Kube, who had no objection to killing Jews in general[88] objected to German Jews, "who come from our own cultural circle", being casually murdered by German soldiers.[89]

Later actions at the site

In 1943, apparently concerned about leaving evidence behind, Himmler ordered that the bodies at Rumbula be dug up and burned. This work was done by a detachment of Jewish slave laborers. Persons travelling on the railway could readily smell the burning corpses.[3]

In 2001, the President of the Republic of Latvia, Vaira Vike-Freiberga, who was a child during World War II, spoke at a 60-year anniversary memorial service about the destruction of the bodies: "We could smell the smoke coming from Rumbula, where corpses were being dug up and burnt to erase the evidence."[90]

Justice

Some of the Rumbula murderers were brought to justice. Hinrich Lohse and Friedrich Jahnke were prosecuted in West German courts and sentenced to terms of imprisonment.[91][92]

Victors Arajs evaded capture for a long time in West Germany, but was finally sentenced to life imprisonment in 1979.[93]

Herberts Cukurs escaped to South America, where he was assassinated, supposedly by agents of Mossad.[94]

Eduard Strauch was convicted in the Einsatzgruppen case and sentenced to death, but he died in prison before the sentence could be carried out.[95]

Friedrich Jeckeln was publicly hanged in Riga on February 3, 1946 following a trial before the Soviet authorities.[96]

Remembrance

On 29 November 2002, a memorial, comprising memorial stones, sculpture and information panels, was unveiled in the forest at the site where the massacre took place.[97]

The center of the memorial is an open area in the form of the Star of David. A sculpture of a menorah stands in the center surrounded by stones bearing the names of Jews murdered at the site. Some of the paving stones bear the names of streets in the former Riga Ghetto.[97]

Concrete frames demarcate the mass graves situated in the memorial grounds.[97]

On the road leading into the forest, a stone marker next to a large metal sculpture states that thousands of people were driven to their deaths along this road and at the entrance to the memorial grounds, stone plaques are inscribed in four languages – Latvian, Hebrew, English and German – with information about the events at Rumbula and the history of memorial.[97]

The memorial was designed by architect Sergey Rizh. Financial contributions to build the memorial were made by individuals and organizations in Germany, Israel, Latvia and the USA.[97]

See also

Notes

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 239.

- Einsatzgruppen trial, p. 16, Indictment, at 6.F: "(F) On 30 November 1941 in Riga, 20 men of Einsatzkommando 2 participated in the murder of 10,600 Jews."

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 4-7, 239-70.

- Edelheit, History of the Holocaust. p. 163: "Aktion Jeckeln, named after its commander, Hoeherer SS- und Polizeiführer Friedrich Jeckeln. Undertaken in the Riga ghetto, the Aktion took place between November 30 and December 7, 1941. During the Aktion some 25,000 Jews were transported to the Rumbula Forest and murdered."

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 211–2.

- Einsatzgruppen judgment, p. 418.

- Riga trial verdict excerpts, as reprinted in Fleming 1994, pp. 78–9.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 33n81.

- Fleming 1994, p. 88.

- As Lohse appeared in 1941 in an announcement in Latvia newspapers following the German occupation.

- Stahlecker report, at 985: "Special detachments reinforced by selected units -- in Lithuania partisan detachments, in Latvia units of the Latvian auxiliary police -- therefore performed extensive executions both in the towns and in rural areas."

- A serious and deadly (approximately 400 Jews murdered) riot in Riga in early July 1941 was one exception.

- Stahlecker, report, at 986: "In Latvia as well the Jews participated in acts of sabotage and arson after the invasion of the German Armed Forces. In Duensburg so many fires were lighted by the Jews that a large part of the town was lost. The electric power station burnt down to a mere shell. The streets which were mainly inhabited by Jews remained unscathed."

- Friedländer, The Years of Extermination, at page 223, refers to the Stahlecker report as evidence that Nazi efforts to induce local pogroms were in general failures in the Baltic states.

- Stahlecker report, at 984-85: "It proved much more difficult to set in motion similar cleansing actions in Latvia. Essentially the reason was that the whole of the national stratum of leaders had been assassinated or destroyed by the Soviets, especially in Riga. It was possible though through similar influences on the Latvian auxiliary to set in motion a pogrom against Jews also in Riga. During this pogrom all synagogues were destroyed and about 400 Jews were murdered. As the population of Riga quieted down quickly, further pogroms were not convenient. So far as possible, both in Kowno and in Riga evidence by film and photo was established that the first spontaneous executions of Jews and Communists were carried out by Lithuanians and Latvians.

- Winter, "Rumbula viewed from the Riga Ghetto, at Rumbula.org

- Stahlecker report, at 987: "In this connection it may be mentioned that some authorities at the Civil Administration offered resistance, at times even a strong one, against the carrying out of larger executions. This resistance was answered by calling attention to the fact that it was a matter of carrying out basic orders."

- Reitlinger, Alibi. p. 186n1.

- Browning, Matthäus. Origins of the Final Solution, pp. 305–7, 406.

- The reply, coming from Brätigam, of Rosenburg's bureau on December 18, 1941, after the murders, was essentially that Lohse should follow instructions from the SS: "Clarification of the Jewish question has most likely been achieved by now through verbal discussions. Economic considerations should fundamentally remain unconsidered in the settlement of the problem. Moreover, it is requested that questions arising be settled directly with the Senior SS and Police Leaders.

- Stahlecker report, at 987: "In Riga the so-called "Moskau suburb" was designated as a Ghetto. This is the worst dwelling district of Riga, already now mostly inhabited by Jews. The transfer of the Jews into the Ghetto-district proved rather difficult because the Latvians dwelling in that district had to be evacuated and residential space in Riga is very crowded, 24,000 of the 28,000 Jews living in Riga have been transferred into the Ghetto so far. In creating the Ghetto, the Security Police restricted themselves to mere policing duties, while the establishment and administration of the Ghetto as well as the regulation of the food supply for the inmates of the Ghetto were left to Civil Administration; the Labor Offices were left in charge of Jewish labor."

- Fleming 1994, plate 3.

- Fleming 1994, pp. 99–100: "There can be no doubt that the Higher SS and Police Leader Friedrich Jeckeln received the KVK First Class with swords in recognition of his faithful performance: his organization of the mass shootings in Riga, 'on orders from the highest level' (auf höchsten Befehl).

- Friedländer, The Years of Extermination, at page 267: "The mass slaughters of October and November 1941 were intended to make space for the new arrivals from the Reich."

- Friedländer, The Years of Extermination, at page 267

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 241: "On November 12, Jeckeln received his order from Himmler to kill the Jews of the Riga ghetto." Other sources give the date of Himmler's order as November 10 or November 11. Fleming, Hitler and the Final Solution, at 75

- Fleming 1994, pp. 75–7.

- Eksteins, Walking Since Daybreak, page 150

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 241–2.

- Jeckeln interrogation excerpts, reprinted in Fleming 1994, pp. 95–100.

- Klee and others, eds., The Good Old Days. pp. 76-86.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 240–1.

- Rubenstein and Roth describe Jeckeln's system (p. 179): "In the western Ukraine, SS General Friedrich Jeckeln notices that the haphazard arrangement of the corpses meant an inefficient use of burial space. More graves would have to be dug than absolutely necessary. Jeckeln solved the problem. He told a colleague at one of the Ukrainian killing sites, 'Today we'll stack them like sardines.' Jeckeln called his solution Sardinenpackung (sardine packing). When this method was employed, the victims climbed into the grave and lay down on the bottom. Cross fire from above dispatched them. Then another batch of victims was ordered into the grave, positioning themselves on top of the corpses in a head-to-foot configuration. They too were murdered by cross-fire from above. The procedure continued until the grave was full."

- The Tribunal's judgment states (p. 444): "In some instances, the slain persons did not fall into the graves, and the executioners were then compelled to exert themselves to complete the job of interment. A method, however, was found to avoid this additional exertion by simply having the victims enter the ditch or grave while still alive. An SS eyewitness explained this procedure.

'The people were executed by a shot in the neck. The corpses were buried in a large tank ditch. The candidates for execution were already standing or kneeling in the ditch. One group had scarcely been shot before the next came and laid themselves on the corpses there.'" - According to the judgment of the Tribunal in the Einsatzgruppen case (p. 448): "It was stated in the early part of this opinion that women and children were to be executed with the men so that Jews, gypsies, and so-called asocials would be exterminated for all time. In this respect, the Einsatzgruppen leaders encountered a difficulty they had not anticipated. Many of the enlisted men were husbands and fathers, and they winced as they pulled their triggers on these helpless creatures who reminded them of their own wives and offspring at home. In this emotional disturbance they often aimed badly and it was necessary for the Kommando leaders to go about with a revolver or carbine, firing into the moaning and writhing forms." This situation was reported to the RSHA in Berlin, and to relieve the emotional sensitivity of the executioners, gas vans were sent as an additional killing system. Angrick & Klein 2012, p. 152.

- From the transcript of the Einsatzgruppen trial:

Ohlendorf: Some of the unit leaders did not carry out the liquidation in the military manner, but murdered the victims singly by shooting them in the back of the neck.

Col. Amen: And you objected to that procedure?

Ohlendorf: I was against that procedure, yes.

Col. Amen: For what reason?

Ohlendorf: Because both for the victims and for those who carried out the executions, it was, psychologically, an immense burden to bear. - Green series, Volume IV, p. 443, quoting Einsatzgruppe commander Paul Blobel.

- The Tribunal's judgment in the Einsatzgruppen case states (p. 444): "In fact, one defendant did not exclude the possibility that an executee could only seem to be dead because of shock or temporary unconsciousness. In such cases it was inevitable he would be buried alive."

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 242.

- Browning. Nazi Policy, p. 143.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 243–5.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 248–9.

- Fleming 1994, pp. 83–7.

- Max Kaufmann, a ghetto survivor, reported one "Altmeyer" as one of the guards forming up the columns of Jews in the ghetto on the morning of November 30, but whether this is the same person with whom Bruns spoke is not clear from the sources. Kaufmann 2010, pp. 60–1.

- Fleming 1994, pp. 80–2

- Michelson, Frida, I Survived Rumbuli, pp. 74-7.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 247–8.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 59-61.

- Browning, Matthäus. Origins of the Final Solution, p. 396.

- Hilberg, Destruction of European Jews. p. 365.

- The Einsatzgruppen judgment stated (p. 418): "In time the authors of the reports apparently tired of the word 'shot' so, within the narrow compass of expression allowed in a military report, some variety was added. A report originating in Latvia read --

'The Higher SS and Police leader in Riga, SS Obergruppenfuehrer Jeckeln, has meanwhile embarked on a shooting action [Erschiessungsaktion] and on Sunday, the 30 November 1941, about 4,000 Jews from the Riga ghetto and an evacuation transport from the Reich were disposed of." (NO-3257)

And so that no one could be in doubt as to what was meant by 'Disposed of', the word 'killed' was added in parentheses." - Roseman, The Wannsee Conference. pp. 75-7.

- Fleming 1994, p. 89.

- Browning. Nazi Policy, pp. 52-4.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 61-2.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 252.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 60-1.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 267n55.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 192, 267.

- The 10 kilometer distance is supplied in Ezergailis 1996b, p. 251.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 251.

- Kaufmann 2010, p. 63.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 253–4.

- Reprinted in Fleming 1994, pp. 95–100.

- Fleming 1994, p. 88.

- Reichskommissariat Ostland was the German name for the Baltic states and nearby areas which they had conquered.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 254.

- Ezergailis 1996b, p. 259.

- Michelson, Frida, I Survived Rumbuli. pp. 77-8.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 63-4.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 64–5.

- Friedlander, The Years of Extermination. pp. 261-3.

- Michelson, Frida, I Survived Rumbuli. pp. 85-8.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 256-7.

- Kaufmann 2010, pp. 68-9.

- Michelson, Frida, I Survived Rubuli. pp. 89-93.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 257–61.

- Kaufmann 2010, p. 150.

- Eksteins, Walking Since Daybreak. p. 150, citing Press, Bernard, Judenmort in Lettland, 1941-1945, Berlin: Metropol 1992. p. 12.

- Dribins, Leo; Gūtmanis, Armands; Vestermanis, Marģers (2001). Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival. Riga: Latvijas Vēsturnieku komisija (Commission of the Historians of Latvia).

- Friedländer, The Years of Extermination. p. 262: "A few months later, on June 26, 1942, SS Obersturmführer Heinz Ballensiefen, head of the Jewish section of Amt VII (research) in the RSHA, informed his colleagues that in Riga his men had secured ("sichergestellt") about 45 boxes containing the archive and library of the Jewish historian Dubnow.

- Kaufmann 2010, p. 70.

- Smith, Remembering. pp. 100, 114, 128, reporting statement of Ruth Foster.

- Reitlinger, Alibi. p. 282: "As early as October 1941 Jews had been sent from Berlin and other Reich cites to the already hopelessly overcrowed Lodz ghetto. Before the end of the year deportations had followed to ghettos in the Baltic states and White Russia."

- Smith, Remembering. p. 113, reporting statement of Ezra Jurmann: "We arrived in the ghetto and were taken to a group of houses which had obviously been left in a hurry: there was complete turmoil, they were completely deserted and they had not been heated. In a pantry there was a pot of potatoes frozen solid. ... Complete chaos. Ominous. On the walls, a message said, 'Mama, farewell.'"

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 254-6.

- Breitman, Architect of Genocide. p. 220, discusses Himmler's concerns about the effect on his men's morale of the mass killings of German Jews at Riga and elsewhere.

- Friedländer, The Years of Extermination. pp. 362-3.

- David Cesarani, Eichmann: His Life and Crimes (Vintage 2005). p. 110.

- "Styopina, Anastasia, "Latvia remembers Holocaust killings 60 years ago" Reuters World Report, November 30, 2001". Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved 2009-03-10.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link).

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial. p. 198.

- Ezergailis 1996b, pp. 16, 245-8.

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial. pp. 197-9.

- Kuenzle, Anton and Shimron, Gad, The Execution of the Hangman of Riga: The Only Execution of a Nazi War Criminal by the Mossad, Valentine Mitchell, London 2004 ISBN 0-85303-525-3.

- Eduard Strauch (German wikipedia).

- Edelheit, History of the Holocaust. p. 340: Jeckeln was " ... responsible for the murder of Jews and Communist Party officials ... convicted and hanged in the former ghetto of Riga on February 3, 1946.

- "Riga, Rumbula: Holocaust Memorial Places in Latvia". Holokausta memoriālās vietas Latvijā. Riga, Latvia: Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Latvia. 2002. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

References

Historiographical

- Anders, Edward, and Dubrovskis, Juris, "Who Died in the Holocaust? Recovering Names from Official Records", Holocaust and Genocide Studies 17.1 (2003) 114-138

- Angrick, Andrej; Klein, Peter (2012). The 'Final Solution' in Riga: Exploitation and Annihilation, 1941-1944. Translation from German by Ray Brandon. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0857456014.

- Bloxham, Donald, Genocide on Trial; war crimes trials and the formation of Holocaust History and Memory, Oxford University Press, New York NY 2001 ISBN 0-19-820872-3

- Browning, Christopher (1999). Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77490-X.

- Browning, Christopher; Matthäus, Jürgen (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5979-9.

- Dribins, Leo, Gūtmanis, Armands, and Vestermanis, Marģers, "Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Trajedy, Revival", Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Latvia

- Edelheit, Abraham J. and Edelheit, Hershel, History of the Holocaust : A Handbook and Dictionary, Westview Press, Boulder, CO 1994 ISBN 0-8133-1411-9

- Eksteins, Modris, Walking Since Daybreak: A story of Eastern Europe, World War II, and the Heart of our Century, Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1999 ISBN 0-395-93747-7.

- Ezergailis, Andrew (1996a). "Latvia". In Wyman, David S.; Rosenzveig, Charles H. (eds.). The World Reacts to the Holocaust. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 354–88. ISBN 0-8018-4969-1.

- Ezergailis, Andrew (1996b). The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941-1944: The Missing Center. Riga / Washington DC: Historical Institute of Latvia and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-9984905433.

- Fleming, Gerald (1994). Hitler and the Final Solution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520060229.

- Friedländer, Saul, The years of extermination : Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945, New York, NY 2007 ISBN 978-0-06-019043-9

- Hilberg, Raul, The Destruction of the European Jews (3d Ed.) Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 2003. ISBN 0-300-09557-0

- Hobrecht,Jürgen "We did survive it"- The Riga Ghetto. Documentary film, Berlin 2013, 98 Min. Outtakes: www.phoenix-medienakademie.com/Riga-survive

- Kaufmann, Max (2010). Churbn Lettland - The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia (PDF). Translation by Laimdota Mazzarins. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86628-315-2.

- Klee, Ernst, Dressen, Willi, and Riess, Volker, eds., The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as seen by its Perpetrators and Bystanders, (English translation) MacMillan Free Press, NY 1991 ISBN 0-02-917425-2

- Latvia Institute, The Holocaust in German-Occupied Latvia

- Michelson, Frida, I Survived Rumbuli, Holocaust Library, New York, NY 1979 ISBN 0-89604-029-1

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia, Holocaust Remembrance - Rumbula Memorial Site Unveiled, December 2002

- Press, Bernard, The Murder of the Jews in Latvia, Northwestern University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8101-1729-0

- Reitlinger, Gerald, The SS—Alibi of a Nation, at 186, 282, Viking Press, New York, 1957 (Da Capo reprint 1989) ISBN 0-306-80351-8

- Roseman, Mark, The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution—A Reassessment, Holt, New York, 2002 ISBN 0-8050-6810-4

- Rubenstein, Richard L., and Roth, John K., Approaches to Auschwitz, page 179, Louisville, Ky. : Westminster John Knox Press, 2003. ISBN 0-664-22353-2

- (in German) Scheffler, Wolfgang, "Zur Geschichte der Deportation jüdischer Bürger nach Riga 1941/1942", Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. – 23.05.2000

- Schneider, Gertrude, Journey into terror: story of the Riga Ghetto, (2d Ed.) Westport, Conn. : Praeger, 2001 ISBN 0-275-97050-7

- Schneider, Gertrude, ed., The Unfinished Road: Jewish Survivors of Latvia Look Back, Praeger Publishers (1991) ISBN 978-0-275-94093-5

- Smith, Lyn, Remembering: Voices of the Holocaust, Carroll & Graf, New York 2005 ISBN 0-7867-1640-1

- Winter, Alfred, "Rumbula Viewed From The Riga Ghetto" from The Ghetto of Riga and Continuance - A Survivor's Memoir 1998

War crimes trials and evidence

- Brätigam, Otto, Memorandum dated 18 Dec. 1941, "Jewish Question re correspondence of 15 Nov. 1941" translated and reprinted in Office of the United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Exhibit 3666-PS, Volume VII, pages 978–995, USGPO, Washington DC 1946 ("Red Series")

- Jeckeln, Friedrich, excerpts from minutes of interrogation, 14 December 1945 (Maj. Zwetajew, interrogator, Sgt. Suur, interpreter), pages 8–13, from the Historical State Archives, as reprinted in Fleming, Hitler and the Final Solution, at pages 95–100 (Portions of the Jeckeln interrogation are also available online at the Nizkor website).

- Stahlecker, Franz W., "Comprehensive Report of Einsatzgruppe A Operations up to 15 October 1941", Exhibit L-180, translated in part and reprinted in Office of the United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume VII, pages 978–995, USGPO, Washington DC 1946 ("Red Series")

- "The International Military Tribunal for Germany". Yale Law School / Lillian Goldman Law Library / The Avalon Project.

- Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, Nuernberg, October 1946 - April 1949, Volume IV, ("Green Series) (the "Einsatzgruppen case") also available at Mazel library (well indexed HTML version)

Further reading

- Katz, Josef, One Who Came Back, University of Wisconsin Press, (2nd Ed. 2006) ISBN 978-1-928755-07-4

- Iwens, Sidney, How Dark the Heavens—1400 Days in the Grip of Nazi Terror, Shengold Publishing (2d ed. 1990) ISBN 978-0-88400-147-8

- Michelson, Max, City of Life, City of Death: Memories of Riga, University Press of Colorado (2001) ISBN 978-0-87081-642-0

External links

- *The Holocaust in Latvia and Latvia's Jews Yesterday and Today

- Remembering Rumbula

- Killed in Rumbala forest

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia, Holocaust Education, Research and Remembrance in Latvia, 16 Sept 2003

- (in German) Berliner Zeitung, Das Lange Warten des Abram Kit, 29 October 1997

(interviews with Rumbula survivors)