Running track

An all-weather running track is a rubberized artificial running surface for track and field athletics. It provides a consistent surface for competitors to test their athletic ability unencumbered by adverse weather conditions. Historically, various forms of dirt, grass, sand and crushed cinders were used. Many examples of these varieties of track still exist worldwide.

Surfaces

Starting in the late 1950s, artificial surfaces using a combination of rubber and asphalt began to appear. An artificial warm-up track was constructed for the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. During the 1960s many of these tracks were constructed; examples still exist today.[1]

In the mid-1960s Tartan tracks were developed, surfaced with a product by 3M. The name Tartan is a trademark, but it is sometimes used as a genericized trademark.[2] This process was the first to commercialize a polyurethane surface for running tracks, though it was originally conceived for horse racing.[3] Many Tartan tracks were installed worldwide, including at many of the top universities in the United States. Among that list was a Tartan track installed in the Estadio Olímpico Universitario, home of the 1968 Summer Olympics at Mexico City, which were the first global championships to use such a track. Olympic shot put champion Bill Nieder was instrumental in developing the product and selling it for this first use in the Olympics.[4] An all-weather surface has become standard ever since.

Another Tartan track was installed on a temporary basis for the 1968 United States Olympic Trials held at altitude at Echo Summit, California, before being moved to South Tahoe Middle School, where it survived for almost 40 years. An original Tartan track is still in place at "Speed City" San Jose State University on a satellite to the campus at 10th Street and Alma. Years of the abuse of tractors tearing it and cars parked on it shows the durability of this original product.

Surfacing tracks have become an industry with many competitors.

- Stobitan® has been installed worldwide since 1991 and is available in a variety of systems.[5]

- Tartan; The legacy of the brand is now known as Tartan APS.[6]

- Chevron 440;[7][8] was a popular surface of the mid-1970s.

- Rekortan; was invented and used for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany[9] and is still licensed worldwide.

- Eurotan.[10]

- Martin ISS[11] was another 1970's development which now goes by the name of the manufacturer Beynon.[12]

- Plexitracs.[13]

- Mondotrack.[14]

There are other techniques that distribute small chunks of rubber then adhere them in place with various polyurethane or latex substances.

World Athletics, international governing body of the sport, publishes very specific regulations for the conduct of a Global Championship or International level track meet (which is their jurisdiction of the sport).[15]

Since the early 1980s, the manufacturer of the surfaces selected for most championship meets has been the Italian company, Mondo, again the trademarked brand name becoming used as a genericized trademark. Mondo's track surface is called Mondotrack. The surface differs from the particles stuck in adhesion techniques, in that they are more of a rubber carpet, cut to size then tightly seamed together (in the linear direction along the lane lines). This form of construction gives a more consistent bounce (or energy return) and traction.[16] Because of the tight fit specifications required for manufacture, construction surrounding these sites also has to be of a higher standard, making a Mondotrack one of the most expensive systems to use. Examples of Mondotracks were used for the 1996 Summer Olympics (since removed from the Centennial Olympic Stadium) in Atlanta, Georgia, United States; 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece; 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China; 2012 Summer Olympics in London, United Kingdom and the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[17][18]

Another player in the marketplace is BASF-owned Conica, which can boast the 2009 World Championships in Athletics in Berlin, Germany (where Usain Bolt improved his 100 metres and 200 metres world records), along with other record hosting venues like Stadio Olimpico in Rome, Italy[19]

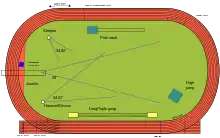

Measurement of a track

The proper length of the 1st lane of a competitive running track is 400 m (1,312.3 ft). Some tracks are not built to this specification, instead some are legacy to imperial distances like 440 yd (402.3 m). Prior to rule changes in 1979, distances in Imperial units were still used in the United States. Some facilities build tracks to fit the available space. One of the most notable examples of this is Franklin Field where the 400 metre distance is achieved in lane 5. Olympic tracks in the early 20th century were of other lengths. Each lane of the track could (by IAAF rules should) be as wide as 122 cm (4.00 ft),[20] though the majority of American tracks are built to NFHS high school specifications that allow smaller lanes.[21] The IAAF also specifies a preferred radius for the turns at 37 metres, but allows a range. Major international level meets are conducted and world records are allowed to be set on tracks that are not exactly 37 metres, but do fall in the range.

Lane measurement

| Lane | Total length | Radius | Semi-circle length | Delta | Angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 400.00 m | 36.80 m | 115.61 m | 0.00 m | 0.00° |

| 2 | 407.67 m | 38.02 m | 119.44 m | 3.83 m | 5.78° |

| 3 | 415.33 m | 39.24 m | 123.28 m | 7.67 m | 11.19° |

| 4 | 423.00 m | 40.46 m | 127.11 m | 11.50 m | 16.28° |

| 5 | 430.66 m | 41.68 m | 130.94 m | 15.33 m | 21.08° |

| 6 | 438.33 m | 42.90 m | 134.77 m | 19.16 m | 25.60° |

| 7 | 446.00 m | 44.12 m | 138.61 m | 23.00 m | 29.86° |

| 8 | 453.66 m | 45.34 m | 142.44 m | 26.83 m | 33.90° |

| 9 | 461.33 m | 46.56 m | 146.27 m | 30.66 m | 37.73° |

- Lane - The ordinal number of the lane with the first lane being on the inside

- Total length - The total length of the lane

- Radius - The radius of the curve 0.30m from the inner side into that lane

- Semi-circle length - The length of the half circle of track at that radius

- Delta - The length a track of this radius is longer than the inside track (and thus how much lead-in is needed to make it a fair race)

- Angle - The corresponding staggering angle (Starting at this offset ensures that a racer in that lane runs the same distance on a curve.)[22][23]

References

- "California and Nevada All-Weather Tracks". Trackinfo.org. 17 February 1997. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- https://www.berleburger.com/en/tartan-track/

- "Tartan - History". Tartan-aps.com. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Bill Nieder: Putter Formulated The Rubber Room". Elitetrack. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- https://stockmeier-urethanes.com/sports-leisure/track-and-field-systems

- "Tartan - The ORIGINAL Polyurethane Athletic Surface". www.tartan-aps.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- http://www.baylorbears.com/school-bio/bay-hart-trackfield.html Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Baylor track history

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Cal Poly track history

- http://precisionsurfaces.com/pages/rekortan/ Archived 19 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Rekortan history

- "Products Eurotan". Totalsportscy.com. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- http://www.beynonsports.com/aboutus/martin_surfacing.aspx Archived 19 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Martin history

- "Beynon Sports - Making fast look good". www.beynonsports.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Plexipave – A California Sports Surfaces Brand". Plexipave.com. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Mondo Spa". Mondotrackusa.com. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Martins, Alejandra (23 July 2012). "Inside line on 2012 Olympics track". BBC News. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- http://www.mondoworldwide.com/Showreferences.cfm?pagina=1&id_root_ref=3&id_applicazione=15

- http://www.iaaf.org/mm/Document/Competitions/TechnicalArea/04/43/20/20091207100318_httppostedfile_Tracks_1Dec09_17528.pdf Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine IAAF Certified Track list

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "IAAF Track and Field Facilities Manual 2008 Edition - Chapters 1-3". IAAF. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "2013 NFHS Rule Book - USA Track & Field" (PDF). NFHS. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "Running Track Geometry". datagenetics.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Schuster, Kurt (11 September 2017). "What Is the Distance Around a Running Track for Each Lane?". LIVESTRONG.COM. Retrieved 1 June 2018.