2004 Summer Olympics

The 2004 Summer Olympics (Greek: Θερινοί Ολυμπιακοί Αγώνες 2004, Therinoí Olympiakoí Agónes 2004),[2] officially known as the Games of the XXVIII Olympiad and commonly known as Athens 2004 (Greek: ΑΘΗΝΑ 2004, Athena 2004), was an international multi-sport event held from 13 to 29 August 2004 in Athens, Greece. The Games saw 10,625 athletes compete,[3][4] some 600 more than expected, accompanied by 5,501 team officials from 201 countries.[3] There were 301 medal events in 28 different sports.[3] Athens 2004 marked the first time since the 1996 Summer Olympics that all countries with a National Olympic Committee were in attendance, and also saw the return of the Olympic Games to the city where they began. Having previously hosted the first modern Olympics in 1896, Athens became one of only four cities to have hosted the Summer Olympic Games on two separate occasions at the time (together with Paris, London and Los Angeles).

| |||

| Host city | Athens, Greece | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | Welcome Home (Greek: Καλώς ήρθατε σπίτι, Kalós írthate spíti) | ||

| Nations | 201 | ||

| Athletes | 10,625 (6,296 men, 4,329 women) | ||

| Events | 301 in 28 sports (40 disciplines) | ||

| Opening | 13 August | ||

| Closing | 29 August | ||

| Opened by | |||

| Cauldron | |||

| Stadium | Olympic Stadium | ||

| Summer | |||

| |||

| Winter | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

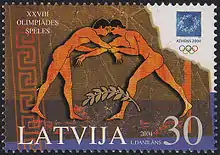

A new medal obverse was introduced at these Games, replacing the design by Giuseppe Cassioli that had been used since 1928. This rectified the long-lasting mistake of using a depiction of the Roman Colosseum rather than a Greek venue;[5] the new design features the Panathenaic Stadium.[6]

The 2004 Olympic Games were hailed as "unforgettable dream games" by IOC President Jacques Rogge, and left Athens with a significantly improved infrastructure, including a new airport, ring road, and subway system.[7] However, there have been arguments (mostly in popular media) regarding the cost of the 2004 Summer Games and their possible contribution to the 2010–18 Greek government-debt crisis, but there is little or no evidence for such a correlation. The 2004 Games were generally deemed to be a success, with the rising standard of competition amongst nations across the world. The final medal tally was led by the United States, followed by China and Russia with Greece at 15th place. Several world and Olympic records were broken during these Games.

Host city selection

Athens was chosen as the host city during the 106th IOC Session held in Lausanne on 5 September 1997. Athens had lost its bid to organize the 1996 Summer Olympics to Atlanta nearly seven years before on 18 September 1990, during the 96th IOC Session in Tokyo. Under the direction of Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, Athens pursued another bid, this time for the right to host the Summer Olympics in 2004. The success of Athens in securing the 2004 Games was based largely on Athens' appeal to Olympic history and the emphasis that it placed on the pivotal role that Greece and Athens could play in promoting Olympism and the Olympic Movement.[8] The bid for the 2004 Games was lauded for its humility and earnestness, its focused message, and its detailed bid concept.[9] The 2004 bid addressed concerns and criticisms raised in its unsuccessful 1996 bid – primarily Athens' infrastructural readiness, its air pollution, its budget, and politicization of Games preparations.[10] Athens' successful organization of the 1997 World Championships in Athletics the month before the host city election was also crucial in allaying lingering fears and concerns among the sporting community and some IOC members about its ability to host international sporting events.[11] Another factor which also contributed to Athens' selection was a growing sentiment among some IOC members to restore the values of the Olympics to the Games, a component which they felt was lost.[12]

After leading all voting rounds, Athens easily defeated Rome in the 5th and final vote. Cape Town, Stockholm, and Buenos Aires, the three other cities that made the IOC shortlist, were eliminated in prior rounds of voting. Six other cities submitted applications, but their bids were dropped by the IOC in 1996. These cities were Istanbul, Lille, Rio de Janeiro, San Juan, Seville, and Saint Petersburg.[13]

| 2004 host city election – ballot results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Country (NOC) | Round 1 | Run-off | Round 3 | Round 4 | Round 5 |

| Athens | 32 | — | 38 | 52 | 66 | |

| Rome | 23 | — | 28 | 35 | 41 | |

| Cape Town | 16 | 62 | 22 | 20 | — | |

| Stockholm | 20 | — | 19 | — | — | |

| Buenos Aires | 16 | 44 | — | — | — | |

Development and preparation

Costs

The 2004 Summer Olympic Games cost the Government of Greece €8.954 billion to stage.[14] According to the cost-benefit evaluation of the impact of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games presented to the Greek Parliament in January 2013 by the Minister of Finance Mr. Giannis Stournaras, the overall net economic benefit for Greece was positive.[15]

The Athens 2004 Organizing Committee (ATHOC), responsible for the preparation and organisation of the Games, concluded its operations as a company in 2005 with a surplus of €130.6 million. ATHOC contributed €123.6 million of the surplus to the Greek State to cover other related expenditures of the Greek State in organizing the Games. As a result, ATHOC reported in its official published accounts a net profit of €7 million.[16][17] The State's contribution to the total ATHOC budget was 8% of its expenditure against an originally anticipated 14%.

The overall revenue of ATHOC, including income from tickets, sponsors, broadcasting rights, merchandise sales etc., totalled €2,098.4 million. The largest percentage of that income (38%) came from broadcasting rights. The overall expenditure of ATHOC was €1,967.8 million.

Often analysts refer to the "Cost of the Olympic Games" by taking into account not only the Organizing Committee's budget (i.e. the organizational cost) directly related to the Olympic Games, but also the cost incurred by the hosting country during preparation, i.e. the large projects required for the upgrade of the country's infrastructure, including sports infrastructure, roads, airports, hospitals, power grid etc. This cost, however, is not directly attributable to the actual organisation of the Games. Such infrastructure projects are considered by all fiscal standards as fixed asset investments that stay with the hosting country for decades after the Games. Also, in many cases these infrastructure upgrades would have taken place regardless of hosting the Olympic Games, although the latter may have acted as a "catalyst".

It was in this sense that the Greek Ministry of Finance reported in 2013 that the expenses of the Greek state for the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, including both infrastructure and organizational costs, reached the amount of €8.5 billion. The same report further explains that €2 billion of this amount was covered by the revenue of the ATHOC (from tickets, sponsors, broadcasting rights, merchandise sales etc.) and that another €2 billion was directly invested in upgrading hospitals and archaeological sites. Therefore, the net infrastructure costs related to the preparation of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games was €4.5 billion, substantially lower than the reported estimates,[18] and mainly included long-standing fixed asset investments in numerous municipal and transport infrastructures.

On the revenue side, the same report estimates that incremental tax revenues of approximately €3.5 billion arose from the increased activities caused by the Athens 2004 Olympic Games during the period 2000 to 2004. These tax revenues were paid directly to the Greek state specifically in the form of incremental social security contributions, income taxes and VAT tax paid by all the companies, professionals, and service providers that were directly involved with the Olympic Games. Moreover, it is reported that the Athens 2004 Olympic Games have had a great economic growth impact on the tourism sector, one of the pillars of the Greek economy, as well as in many other sectors.

The final verdict on the cost of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, in the words of the Greek Minister of Finance, is that "as a result from the cost-benefit analysis, we reach the conclusion that there has been a net economic benefit from the Olympic Games"

The Oxford Olympics Study 2016 estimates the outturn cost of Athens 2004 at US$2.9 billion in 2015-dollars.[19] This figure includes only sports-related costs, that is, (i) operational costs incurred by the organizing committee for the purpose of staging the Games, of which the largest components are technology, transportation, workforce, and administration costs, while other operational costs include security, catering, ceremonies, and medical services, and (ii) direct capital costs incurred by the host city and country or private investors to build the competition venues, the Olympic village, international broadcast center, and media and press center, which are required to host the Games. Indirect capital costs are not included here, such as for road, rail, or airport infrastructure, or for hotel upgrades or other business investment incurred in preparation for the Games but not directly related to staging the Games. Athens 2004 cost of US$2.9 billion compares with costs of US$4.6 billion for Rio 2016, US$40–44 billion for Beijing 2008 and US$51 billion for Sochi 2014, the most expensive Olympics in history. Average sports-related cost for the Summer Games since 1960 is US$5.2 billion.

Cost per sporting event for Athens 2004 was US$9.8 million. This compares with US$14.9 million for Rio 2016, US$49.5 million for London 2012, and US$22.5 million for Beijing 2008. Average cost per event for the Summer Games since 1960 is US$19.9 million.

Cost per athlete for Athens 2004 was US$0.3 million. This compares with US$0.4 million for Rio 2016, US$1.4 million for London 2012, and US$0.6 million for Beijing 2008. Average cost per athlete for the Summer Games since 1960 is US$0.6 million.

Cost overrun for Athens 2004 was 49 percent, measured in real terms from the bid to host the Games. This compares with 51 percent for Rio 2016 and 76 percent for London 2012. Average cost overrun for the Summer Games since 1960 is 176 percent.

Construction

By late March 2004, some Olympic projects were still behind schedule, and Greek authorities announced that a roof it had initially proposed as an optional, non-vital addition to the Aquatics Center would no longer be built. The main Olympic Stadium, the designated facility for the opening and closing ceremonies, was completed only two months before the Games opened. This stadium was completed with a retractable glass roof designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. The same architect also designed the Velodrome and other facilities.

Infrastructure, such as the tram line linking venues in southern Athens with the city centre, and numerous venues were considerably behind schedule just two months before the start of the Games. The subsequent pace of preparation, however, made the rush to finish the Athens venues one of the tightest in Olympics history. The Greeks, unperturbed, maintained that they would make it all along. By July/August 2004, all venues were delivered: in August, the Olympic Stadium was officially completed and opened, joined or preceded by the official completion and openings of other venues within the Athens Olympic Sports Complex (OAKA), and the sports complexes in Faliro and Helliniko.

Late July and early August witnessed the Athens Tram become operational, and this system provided additional connections to those already existing between Athens city centre and its waterfront communities along the Saronic Gulf. These communities included the port city of Piraeus, Agios Kosmas (site of the sailing venue), Helliniko (the site of the old international airport which now contained the fencing venue, the canoe/kayak slalom course, the 15,000-seat Helliniko Olympic Basketball Arena, and the softball and baseball stadia), and the Faliro Coastal Zone Olympic Complex (site of the taekwondo, handball, indoor volleyball, and beach volleyball venues, as well as the newly reconstructed Karaiskaki Stadium for football). The upgrades to the Athens Ring Road were also delivered just in time, as were the expressway upgrades connecting central Athens with peripheral areas such as Markopoulo (site of the shooting and equestrian venues), the newly constructed Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport, Schinias (site of the rowing venue), Maroussi (site of the OAKA), Parnitha (site of the Olympic Village), Galatsi (site of the rhythmic gymnastics and table tennis venue), and Vouliagmeni (site of the triathlon venue). The upgrades to the Athens Metro were also completed, and the new lines became operational by mid-summer.

EMI released Unity, the official pop album of the Athens Olympics, in the leadup to the Olympics.[20] It features contributions from Sting, Lenny Kravitz, Moby, Destiny's Child, and Avril Lavigne.[20] EMI has pledged to donate US$180,000 from the album to UNICEF's HIV/AIDS program in Sub-Saharan Africa.[20]

At least 14 people died during the work on the facilities. Most of these people were not from Greece.[21]

Before the Games, Greek hotel staff staged a series of one-day strikes over wage disputes. They had been asking for a significant raise for the period covering the event being staged. Paramedics and ambulance drivers also protested. They claimed to have the right to the same Olympic bonuses promised to their security force counterparts.

Torch relay

The lighting ceremony of the Olympic flame took place on 25 March 2004 in Ancient Olympia. For the first time ever, the flame travelled around the world in a relay to various Olympic cities (past and future) and other large cities, before returning to Greece.

Mascots

Mascots have been a tradition at the Olympic Games since the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France. The 2004 Olympics had two official mascots: Athena and Phevos (Greek pronunciation: Athina and Fivos). The sister and brother were named after Athena, the goddess of wisdom, strategy and war, and Phoebus, the god of light and music, respectively. They were inspired by the ancient daidala, which were toy dolls that also had religious connotations.

Online coverage

For the first time, major broadcasters were allowed to serve video coverage of the Olympics over the Internet, provided that they restricted this service geographically, to protect broadcasting contracts in other areas.[22] The International Olympic Committee forbade Olympic athletes, as well as coaches, support personnel and other officials, from setting up specialized weblogs and/or other websites for covering their personal perspective of the Games. They were not allowed to post audio, video, or photos that they had taken. An exception was made if an athlete already has a personal website that was not set up specifically for the Games.[23] NBC launched its own Olympic website, NBCOlympics.com. Focusing on the television coverage of the Games, it did provide video clips, medal standings, live results. Its main purpose, however, was to provide a schedule of what sports were on the many stations of NBC Universal. The Games were shown on television 24 hours a day, on one network or another.

Technology

As with any enterprise, the Organizing Committee and everyone involved with it relied heavily on technology in order to deliver a successful event. ATHOC maintained two separate data networks, one for the preparation of the Games (known as the Administrative network) and one for the Games themselves (Games Network). The technical infrastructure involved more than 11,000 computers, over 600 servers, 2,000 printers, 23,000 fixed-line telephone devices, 9,000 mobile phones, 12,000 TETRA devices, 16,000 TV and video devices and 17 Video Walls interconnected by more than 6,000 kilometers of cabling (both optical fiber and twisted pair).

This infrastructure was created and maintained to serve directly more than 150,000 ATHOC Staff, Volunteers, Olympic family members (IOC, NOCs, Federations), Partners & Sponsors and Media. It also kept the information flowing for all spectators, TV viewers, Website visitors and news readers around the world, prior and during the Games. The Media Center was located inside the Zappeion which is a Greek national exhibition center.

Between June and August 2004, the technology staff worked in the Technology Operations Center (TOC) from where it could centrally monitor and manage all the devices and flow of information, as well as handle any problems that occurred during the Games. The TOC was organized in teams (e.g. Systems, Telecommunications, Information Security, Data Network, Staffing, etc.) under a TOC Director and corresponding team leaders (Shift Managers). The TOC operated on a 24x7 basis with personnel organized into 12-hour shifts.

The Games

Opening ceremony

The widely praised Opening Ceremony Directed by avant garde choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou and produced by Jack Morton Worldwide led by Project Director David Zolkwer was held on 13 August 2004. It began with a twenty eight (the number of the Olympiads up to then) second countdown paced by the sounds of an amplified heartbeat.[24] As the countdown was completed, fireworks rumbled and illuminated the skies overhead. After a drum corps and bouzouki players joined in an opening march, the video screen showed images of flight, crossing southwest from Athens over the Greek countryside to ancient Olympia. Then, a single drummer in the ancient stadium joined in a drum duet with a single drummer in the main stadium in Athens, joining the original ancient Olympic Games with the modern ones in symbolism. At the end of the drum duet, a single flaming arrow was launched from the video screen (symbolically from ancient Olympia) and into the reflecting pool, which resulted in fire erupting in the middle of the stadium creating a burning image of the Olympic rings rising from the pool. The Opening Ceremony was a pageant of traditional Greek culture and history hearkening back to its mythological beginnings. The program began as a young Greek boy sailed into the stadium on a 'paper-ship' waving the host nation's flag to aethereal music by Hadjidakis and then a centaur appeared, followed by a gigantic head of a cycladic figurine which eventually broke into many pieces symbolising the Greek islands. Underneath the cycladic head was a Hellenistic representation of the human body, reflecting the concept and belief in perfection reflected in Greek art. A man was seen balancing on a hovering cube symbolising man's eternal 'split' between passion and reason followed by a couple of young lovers playfully chasing each other while the god Eros was hovering above them. There followed a very colourful float parade chronicling Greek history from the ancient Minoan civilization to modern times.

Although NBC in the United States presented the entire opening ceremony from start to finish, a topless Minoan priestess was shown only briefly, the breasts having been pixelated digitally in order to avoid controversy (as the "Nipplegate" incident was still fresh in viewer's minds at the time) and potential fines by the Federal Communications Commission. Also, lower frontal nudity of men dressed as ancient Greek statues was shown in such a way that the area below the waist was cut off by the bottom of the screen. Overall, NBC's coverage of the Olympics has been praised, and the company was awarded with 6 Emmy Awards for its coverage of the Games and technical production.[25][26]

Following the artistic performances, a parade of nations entered the stadium with over 10,500 athletes walking under the banners of 201 nations. The nations were arranged according to Greek alphabet making Finland, Fiji, Chile, and Hong Kong the last four to enter the stadium before the Greek delegation. On this occasion, in observance of the tradition that the delegation of Greece opens the parade and the host nation closes it, the Greek flag bearer opened the parade and all the Greek delegation closed it. Based on audience reaction, the emotional high point of the parade was the entrance of the delegation from Afghanistan which had been absent from the Olympics and had female competitors for the first time. The Iraqi delegation also stirred emotions. Also recognized was the symbolic unified march of athletes from North Korea and South Korea under the Korean Unification Flag.[lower-alpha 1] The country of Kiribati made its debut appearance at these Games and East Timor made a debut under its own flag. After the Parade of Nations, during which the Dutch DJ Tiësto provided the music, the Icelandic singer Björk performed the song Oceania, written specially for the event by her and the poet Sjón.

The Opening Ceremony culminated in the lighting of the Olympic Cauldron by 1996 Gold Medalist Windsurfer Nikolaos Kaklamanakis. Many key moments in the ceremony, including the lighting of the Olympic Cauldron, featured music composed and arranged by John Psathas[27] from New Zealand. The gigantic cauldron, which was styled after the Athens 2004 Olympic Torch, pivoted down to be lit by the 35-year-old, before slowly swinging up and lifting the flame high above the stadium. Following this, the stadium found itself at the centre of a rousing fireworks spectacular.

Participating National Olympic Committees

All National Olympic Committees (NOCs) except Djibouti participated in the Athens Games. Two new NOCs had been created since 2000 and made their debut at these Games (Kiribati and East Timor). Therefore, with the return of Afghanistan (who had been banned from the 2000 Summer Olympics), the number of participating nations increased from 199 to 202. Also since 2000, Yugoslavia had changed its name to Serbia and Montenegro and its code from YUG to SCG.

In the table below, the number in parentheses indicates the number of participants contributed by each NOC.

Sports

The sports featured at the 2004 Summer Olympics are listed below. Officially there were 301 events in 28 sports as swimming, diving, synchronised swimming and water polo are classified by the IOC as disciplines within the sport of aquatics, and wheelchair racing was a demonstration sport. For the first time, the wrestling category featured women's wrestling and in the fencing competition women competed in the sabre. American Kristin Heaston, who led off the qualifying round of women's shot put became the first woman to compete at the ancient site of Olympia.

The demonstration sport of wheelchair racing was a joint Olympic/Paralympic event, allowing a Paralympic event to occur within the Olympics, and for the future, opening up the wheelchair race to the able-bodied. The 2004 Summer Paralympics were also held in Athens, from 17 to 28 September.

| 2004 Summer Olympic Sports Programme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gallery

Archery rounds in the Panathenaic Stadium

Archery rounds in the Panathenaic Stadium

Russian Igor Turchin (left) and American Weston Kelsey (right) duel in second round of men's individual épée

Russian Igor Turchin (left) and American Weston Kelsey (right) duel in second round of men's individual épée

Calendar

- All times are in Eastern European Summer Time (UTC+3)

| OC | Opening ceremony | ● | Event competitions | 1 | Gold medal events | CC | Closing ceremony |

| August | 11th Wed | 12th Thu | 13th Fri | 14th Sat | 15th Sun | 16th Mon | 17th Tue | 18th Wed | 19th Thu | 20th Fri | 21st Sat | 22nd Sun | 23rd Mon | 24th Tue | 25th Wed | 26th Thu | 27th Fri | 28th Sat | 29th Sun | Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | CC | N/A | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aquatics | 2 | 2 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | 44 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 46 | ||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 5 | 6 | 11 | ||||||

| Canoeing | ● | 2 | ● | 2 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cycling | 1 | 1 | 2 | 18 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | 2 | ● | 1 | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Gymnastics | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 18 | ||||||||||||

| ● | ● | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 7 | 7 | 14 | |||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | 2 | ● | ● | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 | |||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 17 | ||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Volleyball | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |||||||||||

| ● | 4 | ● | 4 | 3 | ● | 4 | 3 | 14 | |||||||||||||

| Daily medal events | 13 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 21 | 15 | 21 | 30 | 27 | 20 | 12 | 18 | 15 | 21 | 34 | 17 | 301 | ||||

| Cumulative total | 13 | 25 | 39 | 50 | 71 | 86 | 107 | 137 | 164 | 184 | 196 | 214 | 229 | 250 | 284 | 301 | 301 | ||||

| August | 11th Wed | 12th Thu | 13th Fri | 14th Sat | 15th Sun | 16th Mon | 17th Tue | 18th Wed | 19th Thu | 20th Fri | 21st Sat | 22nd Sun | 23rd Mon | 24th Tue | 25th Wed | 26th Thu | 27th Fri | 28th Sat | 29th Sun | Events | |

31 sports

Highlights

- The shot put event was held in ancient Olympia, site of the ancient Olympic Games (that is the very first time women athletes competed in Ancient Olympia), while the archery competition and the men's and women's marathon finish were held in the Panathenaic Stadium, in which the 1896 Games were held.[29]

- Kiribati and Timor Leste participated in the Olympic Games for the first time.[29]

- Women's wrestling and women's sabre made their Olympic debut at the 2004 Games.[29]

- With 6 gold, 6 silver, and 4 bronze medals, Greece had its best medal tally in over 100 years (since hosting the 1896 Olympics), continuing the nation's sporting success after winning Euro 2004 in July.

- The marathon was held on the same route as the 1896 Games, beginning in the site of the Battle of Marathon to the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens.[29]

- Australia became the first country in Olympic history to win more gold medals (17) immediately after hosting the Olympics in Sydney 2000 where they won 16 gold medals.

- World record holder and strong favourite Paula Radcliffe crashes out of the women's marathon in spectacular fashion, leaving Mizuki Noguchi to win the gold.

- While leading in the men's marathon with less than 10 kilometres to go, Brazilian runner Vanderlei Cordeiro de Lima is attacked by Irish priest Neil Horan and dragged into the crowd. De Lima recovered to take bronze, and was later awarded the Pierre de Coubertin medal for sportsmanship.[29] Twelve years later, at the opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympics, he lit the Olympic Cauldron at Maracana Stadium.

- British athlete Kelly Holmes wins gold in the 800 m and 1500 m.[29]

- Liu Xiang wins the first ever gold medal in men's track and field for China in the 110 m hurdles, equalling Colin Jackson's 1993 World Record time of 12.91 seconds.

- Kenyan runners swept the medals in the 3000 meters steeple chase.[29]

- The Olympics saw Afghanistan's first return to the Games since 1996 (it was banned due to the Taliban's extremist attitudes towards women, but was reinstated in 2002).

- Hicham El Guerrouj wins gold in the 1500 m and 5000 m. He is the first person to accomplish this feat at the Olympics since Paavo Nurmi in 1924.[29]

- Greek athlete Fani Halkia comes out of retirement to win the 400 m hurdles.

- The US women's 4×200 m swimming team of Natalie Coughlin, Carly Piper, Dana Vollmer and Kaitlin Sandeno won gold, smashing the long-standing world record set by the German Democratic Republic in 1987.

- The United States lost for the first time in Olympic men's basketball since the introduction of professional players in 1992. This defeat came at the hands of Puerto Rico 92–73.

- Argentina won a thrilling victory over the United States in the semi-finals of men's basketball. They went on to beat Italy 84–69 in the final.

- Windsurfer Gal Fridman wins Israel's first-ever gold medal.

- Dominican athlete Félix Sánchez won the first ever gold medal for the Dominican Republic in the 400 m hurdles event.

- German kayaker Birgit Fischer wins gold in the K-4 500 m and silver in the K-2 500 m. In so doing, she became the first woman in any sport to win gold medals at 6 different Olympics, the first woman to win gold 24 years apart and the first person in Olympic history to win two or more medals in five different Games.

- Swimmer Michael Phelps became the first athlete to win 8 medals (6 gold and 2 bronze) in non-boycotted Olympics.[29]

- United States' gymnast Carly Patterson becomes the second American woman to win the all-around gold medal, and the first American woman to win the all-around competition at a non-boycotted Olympic Games.

- Chilean Tennis players Nicolás Massu and Fernando Gonzalez won the gold medal in the Doubles Competition, while Massu won the gold and Gonzalez the bronze on the Singles competition. These were Chile's first-ever gold medals. With these victories, Massú became the thirteenth Tennis player (and the eighth male player) in history to have won the gold medal in both the Singles and Doubles Competition during the same Olympic Games. He also became the second Tennis player, and first male player, to have achieved this feat in modern Olympic Tennis (1988 onwards). The first player to do so was Venus Williams in 2000.[29]

- Usain Bolt of Jamaica, in his first career Olympic Games, finishes fifth in his 200m dash heat in 21.05 seconds, failing to qualify for the second round. In the years to come, he would go on to become the world's fastest man, with multiple world records in the 100m, 200m and 4×100m and a medal count of over 29 global medals, including 8 Olympic gold medals and 11 World Championships gold medals.

Closing ceremony

The Games were concluded on 29 August 2004. The closing ceremony was held at the Athens Olympic Stadium, where the Games had been opened 16 days earlier. Around 70,000 people gathered in the stadium to watch the ceremony.

The initial part of the ceremony interspersed the performances of various Greek singers, and featured traditional Greek dance performances from various regions of Greece (Crete, Pontos, Thessaly, etc.). The event was meant to highlight the pride of the Greeks in their culture and country for the world to see.

A significant part of the closing ceremony was the exchange of the Olympic flag of the Athens Games between the mayor of Athens and the mayor of Beijing, host city of the next Olympics. After the flag exchange a presentation from the Beijing delegation presented a glimpse into Chinese culture for the world to see. Beijing University students (who were at first incorrectly cited as the Twelve Girls Band) sang Mo Li Hua (Jasmine Flower) accompanied by a ribbon dancer, then some male dancers did a routine with tai-chi and acrobatics, followed by dancers from the Peking Opera and finally, a little Chinese girl singing a reprise of Mo Li Hua and concluded the presentation by saying "Welcome to Beijing!"

The medal ceremony for the last event of the Olympics, the men's marathon, was conducted, with Stefano Baldini from Italy as the winner. The bronze medal winner, Vanderlei Cordeiro de Lima of Brazil, was simultaneously announced as a recipient of the Pierre de Coubertin medal for his bravery in finishing the race despite being attacked by a rogue spectator while leading with 7 km to go.

A flag-bearer from each nation's delegation then entered along the stage, followed by the competitors en masse on the floor.

Short speeches were presented by Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, President of the Organising Committee, and by President Dr. Jacques Rogge of the IOC, in which he described the Athens Olympics as "unforgettable, dream Games".[7]

Dr. Rogge had previously declared he would be breaking with tradition in his closing speech as President of the IOC and that he would never use the words of his predecessor Juan Antonio Samaranch, who used to always say 'these were the best ever games'.[7] Dr. Rogge had described Salt Lake City 2002 as "superb games" and in turn would continue after Athens 2004 and describe Turin 2006 as "truly magnificent games."

The national anthems of Greece and China were played in a handover ceremony as both nations' flags were raised. The Mayor of Athens, Dora Bakoyianni, passed the Olympic Flag to the Mayor of Beijing, Wang Qishan. After a short cultural performance by Chinese actors, dancers, and musicians directed by eminent Chinese director Zhang Yimou, Rogge declared the 2004 Olympic Games closed. The Olympic flag was next raised again on 10 February 2006 during the opening ceremony of the next Winter Olympics in Torino.

A young Greek girl, 10-year-old Fotini Papaleonidopoulou, lit a symbolic lantern with the Olympic Flame and passed it on to other children before "extinguishing" the flame in the cauldron by blowing a puff of air. The ceremony ended with a variety of musical performances by Greek singers, including Dionysis Savvopoulos, George Dalaras, Haris Alexiou, Anna Vissi, Sakis Rouvas, Eleftheria Arvanitaki, Alkistis Protopsalti, Antonis Remos, Michalis Hatzigiannis, Marinella, and Dimitra Galani, as thousands of athletes carried out symbolic displays on the stadium floor.

Medal count

These are the top ten nations that won medals in the 2004 Games.

* Host nation (Greece)

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 39 | 26 | 101 | |

| 2 | 32 | 17 | 14 | 63 | |

| 3 | 28 | 26 | 36 | 90 | |

| 4 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 50 | |

| 5 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 37 | |

| 6 | 13 | 16 | 20 | 49 | |

| 7 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 33 | |

| 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 32 | |

| 9 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 30 | |

| 10 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 30 | |

| 11–74 | Remaining | 120 | 136 | 156 | 412 |

| Totals (74 nations) | 301 | 300 | 326 | 927 | |

Venues

OAKA

- Athens Olympic Aquatic Centre – diving, swimming, synchronized swimming, water polo

- Athens Olympic Tennis Centre – tennis

- Athens Olympic Velodrome – cycling (track)

- Olympic Indoor Hall – basketball (final), gymnastics (artistic, trampolining)

- Olympic Stadium – ceremonies (opening/ closing), athletics, football (final)

HOC

- Fencing Hall – fencing

- Helliniko Indoor Arena – basketball, handball (final)

- Olympic Baseball Centre – baseball

- Olympic Canoe/Kayak Slalom Centre – canoeing (slalom)

- Olympic Hockey Centre – field hockey

- Olympic Softball Stadium – softball

Faliro

- Faliro Olympic Beach Volleyball Centre – volleyball (beach)

- Faliro Sports Pavilion Arena – handball, taekwondo

- Peace and Friendship Stadium – volleyball (indoor)

GOC

- Goudi Olympic Hall – badminton

- Olympic Modern Pentathlon Centre – modern pentathlon

MOC

- Markopoulo Olympic Equestrian Centre – equestrian

- Markopoulo Olympic Shooting Centre – shooting

Football venues

Other venues

- Agios Kosmas Olympic Sailing Centre – sailing

- Ano Liosia Olympic Hall – judo, wrestling

- Galatsi Olympic Hall – gymnastics (rhythmic), table tennis

- Kotzia Square – cycling (individual road race)

- Marathon (city) – athletics (marathon start)

- Nikaia Olympic Weightlifting Hall – weightlifting

- Panathenaic Stadium – archery, athletics (marathons finish)

- Peristeri Olympic Boxing Hall – boxing

- Schinias Olympic Rowing and Canoeing Centre – canoeing (sprint), rowing

- Stadium at Olympia – athletics (shot put)

- Vouliagmeni Olympic Centre – cycling (individual time trial), triathlon

Sponsors

| Sponsors of the 2004 Summer Olympics |

|---|

| Worldwide Olympic Partners |

| Grand Sponsors |

Official Supporters

|

| Official Providers |

Legacy

To commemorate the 2004 Olympics, a series of Greek high value euro collectors' coins were minted by the Mint of Greece, in both silver and gold. The pieces depict landmarks in Greece as well as ancient and modern sports on the obverse of the coin. On the reverse, a common motif with the logo of the Games, circled by an olive branch representing the spirit of the Games.

Preparations to stage the Olympics led to a number of positive developments for the city's infrastructure. These improvements included the establishment of Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport, a modern new international airport serving as Greece's main aviation gateway;[30] expansions to the Athens Metro[31] system; the "Tram", a new metropolitan tram (light rail) system[32] system; the "Proastiakos", a new suburban railway system linking the airport and suburban towns to the city of Athens; the "Attiki Odos", a new toll motorway encircling the city,[33] and the conversion of streets into pedestrianized walkways in the historic center of Athens which link several of the city's main tourist sites, including the Parthenon and the Panathenaic Stadium (the site of the first modern Olympic Games in 1896).[34][35] All of the above infrastructure is still in use to this day, and there have been continued expansions and proposals to expand Athens' metro, tram, suburban rail and motorway network, the airport, as well as further plans to pedestrianize more thoroughfares in the historic center of Athens.

The Greek Government has created a corporation, Olympic Properties SA, which is overseeing the post-Olympics management, development and conversion of these facilities, some of which will be sold off (or have already been sold off) to the private sector,[36][37] while some other facilities are still in use, or have been converted for commercial use or modified for other sports.[38]

As of 2012 many conversion schemes have stalled owing to the Greek government-debt crisis, though many of these facilities are now under the control of domestic sporting clubs and organizations or the private sector.

The table below delineates the current status of the Athens Olympic facilities:

| Facility | Olympics use | Current/Proposed use |

|---|---|---|

| Athens Olympic Stadium (OAKA) | Opening & Closing Ceremonies, Track & Field, Football | Home pitch for Panathinaikos FC,[39] AEK FC[40] (football; Greek Super League, UEFA Champions League), Greek national football team (some matches), International football competitions;[41] Track & Field events (e.g. IAAF Athens Grand Prix[42]), Concerts[43][44][45] |

| Athens Olympic Indoor Hall | Basketball, Gymnastics | Home court for Panathinaikos BC[46] and AEK BC[47] (Greek basketball league); Greek National Basketball Team, International basketball competitions,[48] Concerts[49][50] |

| Athens Olympic Aquatic Centre | Swimming, Diving, Synchronized Swimming, Water Polo | Domestic and international swimming meets,[51][52][53] Public pool,[54] domestic league and European water-polo games. |

| Athens Olympic Tennis Centre | Tennis | Domestic and international tennis matches, training courts open to the public and home of the Athens Tennis Academy, currently the best-kept facility in the complex[55][56] |

| Athens Olympic Velodrome | Cycling | Domestic and international cycling meets[57] |

| Peace and Friendship Stadium | Volleyball | Home court for Olympiacos BC (basketball),[58] Concerts, Conventions and trade shows[59] |

| Helliniko Olympic Indoor Arena | Basketball, Handball | Home court for Panionios BC (basketball),[60] Conventions and trade shows[54] |

| Hellinikon Canoe/Kayak Slalom Centre | Canoe/Kayak | Turned over to a private consortium (J&P AVAX, GEP, Corfu Waterparks and BIOTER), plans to convert it to a water park,[61][62] although currently it is abandoned. |

| Hellinikon Olympic Hockey Centre | Field Hockey | Mini-football, will be part of new Hellinikon metropolitan park complex[63] |

| Hellinikon Baseball Stadium | Baseball | Main ground (no. 1) converted to football pitch, home field of Ethnikos Piraeus F.C. (Football; Greek second division),[64] auxiliary ground (no. 2) abandoned. |

| Hellinikon Softball Stadium | Softball | Abandoned[63] |

| Agios Kosmas Olympic Sailing Centre | Sailing | Currently out of use, turned over to the private sector (Seirios AE), will become marina with 1,000+ yacht capacity[65] and will be part of Athens' revitalized waterfront[66] |

| Ano Liosia Olympic Hall | Judo, Wrestling | TV filming facility,[54] Future home of the Hellenic Academy of Culture and Hellenic Digital Archive[67][68] |

| Olympic Beach Volleyball Centre | Beach Volleyball | Concert and theater venue, it hosted Helena Paparizou's concert on 13 August 2005 to celebrate the first anniversary of the Olympic Games, currently sees minimal usage[69] plans to turn it into an ultra-modern outdoor theater[54] |

| Faliro Sports Pavilion | Handball, Taekwondo | Converted to the Athens International Convention Center, hosts concerts, conventions and trade shows[54][68][70][71][72] |

| Galatsi Olympic Hall | Table Tennis, Rhythmic Gymnastics | After 2004, was the home court of AEK BC (basketball) before the team moved to the Athens Olympic Indoor Hall. Turned over to the private sector (Acropol Haragionis AE and Sonae Sierra SGPS S.A), being converted to a shopping mall and retail/entertainment complex.[73] |

| Goudi Olympic Complex | Badminton, Modern Pentathlon | Now the site of the ultra-modern Badminton Theater, hosting major theatrical productions[74][75] |

| Markopoulo Olympic Equestrian Centre | Equestrian | Horse racing,[76] Domestic and International Equestrian meets,[77][78] Auto racing (rallye)[79] |

| Markopoulo Olympic Shooting Centre | Shooting | Converted to the official shooting range and training center of the Hellenic Police.[65][80] |

| Nikaia Olympic Weightlifting Hall | Weightlifting | Has hosted fencing competitions in the years following the Olympics,[54] but has recently been turned over to the University of Piraeus for use as an academic lecture and conference center.[68][81] |

| Parnitha Olympic Mountain Bike Venue | Mountain Biking | Part of the Parnitha National Park. In public use for biking and hiking.[82][83] |

| Peristeri Olympic Boxing Hall | Boxing | Partially converted to a football pitch, also in use for gymnastics competitions.[54] |

| Schinias Olympic Rowing and Canoeing Centre | Rowing and Canoeing | One of only three FISA-approved training centers in the world, the others being in Munich and Seville.[65] Hosts mainly domestic rowing and canoeing meetings.[84][85] Part of the Schinias National Park, completely reconstructed by the German company Hochtief.[54] |

| Vouliagmeni Olympic Centre | Triathlon | Temporary facility, not in existence presently. |

| Kaftanzoglio Stadium | Football | Home pitch for Iraklis FC (football; Greek Super League)[86] and temporary home pitch for Apollon Kalamarias FC (football; Greek second division).[87] Also in use for track and field meets.[88] Hosted the 2007 Greek football All-Star Game. |

| Karaiskaki Stadium | Football | Home pitch for Olympiacos FC (football; Greek Super League)[89] and for the Greek National Football team. Also used as a concert venue. |

| Pampeloponnisiako Stadium | Football | Home pitch for Panahaiki FC (football; Greek third division).[90] Also used for various track-and-field events, concerts, conventions, and friendly matches of the Greek National Football Team.[54] |

| Pankritio Stadium | Football | Home pitch for OFI FC[91][92] and Ergotelis FC (football; Greek Super League).[92][93] Hosted the 2005 Greek football All-Star game. Also home to various track-and-field meets.[54] |

| Panthessaliko Stadium | Football | Home pitch for Niki Volou FC (football; Greek third division).[54] Has also hosted concerts, conventions and track-and-field meets.[54] |

| Panathainaiko Stadium | Marathon, Archery | Site of the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. One of Athens' major tourist attractions, also used for occasional sporting and concert events.[94][95][96][97] |

| The Ancient Stadium at Olympia | Track and Field | One of Greece's historic sites and largest tourist attractions, open to the public to this day.[98] |

| International Broadcast Centre (IBC) | International Broadcast Centre | Half of it (the section fronting Kifissias Avenue) has been turned over to the private company Lambda Development SA and has been converted to a luxury shopping, retail, office and entertainment complex known as the "Golden Hall."[99] The remaining section, facing the Olympic Stadium itself, will become home to the Hellenic Olympic Museum and the International Museum of Classical Athletics.[54][68][100] |

| Olympic Athletes' Village | Housing | 2,292 apartments were sold to low-income individuals and today the village is home to over 8,000 residents.[54] Several communal installations however are abandoned and heavily vandalised. |

| Olympic Press Village | Housing | It has been turned over to the private sector and namely Lamda Developments S.A. (the same company which owns and runs the Mall of Athens and the Golden Hall), and has been converted to luxury flats. |

Arguments about possible effects on Greece's debt crisis

There have been arguments (mostly in popular media) that the cost of the 2004 Athens Summer Games was a contributor to the Greek government-debt crisis that started in 2010, with a lot of focus on the use of the facilities after the Games.[101] This argument, however, contradicts the fact that Greece's Debt to GDP ratio was essentially not affected until the 2008 world financial crisis,[102] while the cost of the Games, spread over years of preparation, was insignificant compared to Greece's public debt and GDP.[103][104] Furthermore, the aforementioned arguments do not even take into account the profits (direct and indirect) generated by the Games, which may well have surpassed the above costs. Finally, popular arguments about "rotting" of many of the facilities, appear to ignore the actual utilization of most of these structures.[104]

See also

- 2004 Summer Paralympics

- Olympic Games celebrated in Greece

- 1896 Summer Olympics – Athens

- 2004 Summer Olympics – Athens

Notes

- The national teams of North Korea and South Korea competed separately in the Olympic events, even though they marched together as a unified Korean team in the opening ceremony.

References

- "Factsheet - Opening Ceremony of the Games of the Olympiad" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Standard Greek pronunciation is [θeriˈni olibi.aˈci aˈɣones ðˈio çiˈʎaðes ˈtesera]

- "Athens 2004". International Olympic Committee. olympic.org. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- "The Olympic Summer Games Factsheet" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- Winner Medals Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Olympic Games Museum. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Athens' New Olympic Medal Design Win IOC's Nod, People Daily. Accessed 5 August 2011.

- "Rogge: Athens 'unforgettable, dream Games'". ESPN. Associated Press. 29 August 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Weisman, Steven R. (19 September 1990). "Atlanta Selected Over Athens for 1996 Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Rowbottom, Mike (6 September 1997). "Athens wins 2004 Olympics". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Longman, Jere (6 September 1997). "Athens Wins a Vote for Tradition, and the 2004 Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Longman, Jere (3 August 1997). "Athens Pins Olympic Bid to World Meet". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Anderson, Dave (7 September 1997). "Athens Can Thank Atlanta for 2004 Games". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "International Olympic Committee – Athens 2004 – Election". Olympic.org. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Cost of Athens 2004 Olympics". Embassy of Greek. greekembassy.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2004.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- "Published Accounts of the ATHENS 2004 Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games, Greek Official Gazette, FEK5395/2005".

- "Olympics 'may cost Greece dear'". 2 June 2004 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent; Stewart, Allison; Budzier, Alexander (2016). The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games. Oxford: Saïd Business School Working Papers (Oxford: University of Oxford). pp. 18–20. SSRN 2804554.

- "Unity Olympics Album". The Star Online eCentral. 2004. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- "Workers in peril at Athens sites". BBC News. 23 July 2004. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Pfanner, Eric (30 August 2004). "Athens Games beating Sydney in TV race". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- "You're Athletes, Not Journalists". Wired News. 20 August 2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- "Master of Olympic Pageantry Prepares One Final Blowout". The New York Times. Associated Press. 29 August 2004. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Athens Olympics close, and NBC cashes in - Aug. 30, 2004". money.cnn.com.

- Grohmann, Karolos (19 January 2005). "Olympics chief rebuffs lewd claims". Reuters. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "SOUNZ – NZ composer – John Psathas". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Matthews, Peter (22 March 2012). Historical Dictionary of Track and Field. Scarecrow Press. p. xciv.

- "Athens 2004". IOC. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- "The Company". Aia.gr. 28 March 2001. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "AttikoMetro Inside". Ametro.gr. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Tram Sa". Tramsa.gr. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Unification of Archaeological Sites in the Centre of Athens". Minenv.gr. 4 November 1995. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "As Olympic Glow Fades, Athens Questions $15 Billion Cost". Csmonitor.com. 21 July 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Hellenic Olympic Properties: The Company". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "After The Party: What happens when the Olympics leave town". The Independent. London. 19 August 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- (AFP) – 30 July 2008 (30 July 2008). "Four years after Athens Greeks have Olympics blues". Google. Archived from the original on 6 August 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Archived 16 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "AEK F.C. Official Web Site". Aekfctickets.gr. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- McNulty, Phil (23 May 2007). "BBC SPORT | Football | Europe | AC Milan 2–1 Liverpool". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Athens Grand Prix 2009". Tsiklitiria.org. 13 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "ATHENS, GREECE CONCERT, SAT. September 20, 2008 | The Official Jennifer Lopez Site". Jenniferlopez.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. Archived from the original on 27 April 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Panathinaikos Bc::::Εδρα::::". Paobc.gr. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "AEK B.C. | Official Web Site". Aekbc.gr. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- "www.athens2008.fiba.com – Home page". Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- "Pop icon set for show in Athens this September". ekathimerini.com. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Eurovision Song Contest 2006 Final | Year page | Eurovision Song Contest – Oslo 2010". Eurovision.tv. 20 May 2006. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. 22 March 2008. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. 16 July 2006. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Athens Tennis Academy". Athenstennisacademy.gr. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακό Αθλητικό Κέντρο Αθηνών". Oaka.com.gr. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Αρχειο Εκδηλωσεων". Sef-stadium.gr. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Πανιωνιοσ – Κ.Α.Ε". Panioniosbc.gr. 20 October 2009. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "High hopes for park at Hellenikon". ekathimerini.com. 3 August 2007. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- etipos/

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Εθνικός". Sport.gr. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Η πορεία της μεταολυμπιακής αξιοποίησης των Ολυμπιακών Ακινήτων". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Renzo Piano Chosen to Design New Greek Opera, Library Complex". Bloomberg. 21 February 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Media

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: GFestival 2005". Olympicproperties.gr. 15 June 2005. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Isaac Hayes Στο Κλειστο Φαληρου". i-stores.gr. Archived from the original on 22 December 2005. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Κλειστό Γυμναστήριο Φαλήρου – Morrissey | Siteseein.gr Blog". Siteseein.gr. 27 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Metaforce – Fuel. "Badminton Theater". Badmintontheater.gr. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Ολυμπιακό Κέντρο Γουδή". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Horse Racing | Hellas Vegas". Hellasvegas.gr. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "FEI European Jumping Championship for Children – Markopoulo (GRE), 10–13 July 2008". Hunter Jumper News. 30 June 2008. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Ελληνική Ομοσπονδία Ιππασίας – Αγωνιστικό Πρόγραμμα 2008". Olympicproperties.gr. 24 May 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "The Subaru Enthuisast Website". Subdriven. 25 May 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα: Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση". Olympicproperties.gr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ανακοινώσεις, Εκδηλώσεις, Νέα". Unipi.gr. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ορεινη Ποδηλασια". Parnitha-np.gr. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Parnitha Olympic Mountain Bike Venue – Attraction in Athens, Greece – Ratings and Information". TravelMuse. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "eurorowing-2008.com". eurorowing-2008.com. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- WebSide Associates SA. "Official Website". World Rowing. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "IRAKLIS FC Official Web site". Iraklis-fc.gr. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Archived 5 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Καυτανζόγλειο Στάδιο – Θεσσαλονίκη". Kaftanzoglio.gr. 27 August 2004. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- George Xenides. "Georgios Karaiskakis Stadium". Stadia.gr. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Site Map". Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- "EISITIRIA DIARKEIAS 2008-09.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- George Xenides (20 February 2005). "Παγκρήτιο Στάδιο". Stadia.gr. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Παε Διεθνησ Ενωσισ Εργοτελησ". Ergotelis.gr. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism | Panathenaic Stadium". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "news in.gr – Δωρεάν συναυλία στο Καλλιμάρμαρο δίνουν οι R.E.M". In.gr. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Πρόγραμμα Τηλεοπτικών Σειρών - e-go.gr". Πρόγραμμα Τηλεοπτικών Σειρών - e-go.gr. Archived from the original on 11 September 2008.

- "Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism | Olympia". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Lamda Development". Lamda Development. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Ελλάδα – Ευρώπη – Κόσμος : Η ζωή έχει χρώμα". fe-mail.gr. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Olympic Cities: Booms and Busts". Cnbc.com. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "2010-2018 Greek Debt Crisis and Greece's Past: Myths, Popular Notions and Implications". Academia.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Did 2004 Olympics Spark Greek Financial Crisis?". CNBC. 3 June 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Nevradakis, Michael (7 August 2012). "The True Olympic Legacy of Athens: Refuting the Mythology". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

External links

| External video | |

|---|---|

Media related to 2004 Summer Olympics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 2004 Summer Olympics at Wikimedia Commons- "Athens 2004". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- Official website

- Pictures from the opening ceremony

- Project to fly the 2004 Olympic Flame around the world on a B747 aircraft

- Pictures backstage from the opening ceremony

- 2004 Athens Olympics at Curlie

- BBC coverage

| Preceded by Sydney |

Summer Olympic Games Athens XXVIII Olympiad (2004) |

Succeeded by Beijing |