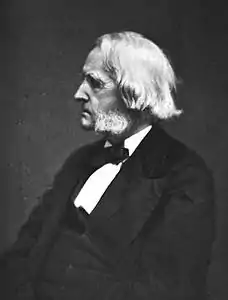

Samuel Edmund Sewall

Samuel Edmund Sewall (1799-1888) was an American lawyer, abolitionist, and suffragist. He was one of the founders of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in 1831, lent his legal expertise to the Underground Railroad, and served a term in the Massachusetts Senate as a Free-Soiler.

Samuel Edmund Sewall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 9, 1799 Boston, U.S. |

| Died | December 20, 1888 (aged 89) Boston, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Harvard College Harvard Law School |

| Spouse(s) | Louisa Winslow (1836-50) Harriet Winslow (1857-88) |

| Children | Lucy Ellen Sewall Louisa Winslow Sewall |

Sewall was involved in several notable cases involving refugees from slavery, including George Latimer, Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, Eliza Small, and Polly Ann Bates. He also worked to advance women's legal rights in Massachusetts.

He was a descendant of the Puritan judge Samuel Sewall.

Early life and education

Sewall was born in Boston on November 9, 1799,[note 1] the seventh of eleven children of Joseph Sewall and Mary (Robie) Sewall. Joseph Sewall, a great-grandson of Chief Justice Samuel Sewall, was a partner in a dry goods import business, Sewall & Salisbury, and the treasurer of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Of Samuel's siblings, four died in infancy and five more died young, of consumption (tuberculosis). Samuel and his older brother Thomas were the only ones who survived their mother, who died in 1834.[1]

After attending Phillips Exeter Academy, Samuel entered Harvard College at the age of 13, graduating in 1817 near the top of his class. Many of his classmates at Harvard went on to distinguished careers: historian George Bancroft, politicians Caleb Cushing and Samuel A. Eliot, journalist David Lee Child, educators George B. Emerson and Alva Woods, noted clergyman Stephen H. Tyng, and reformer Samuel J. May (Sewall's cousin). In the fall of 1817 he entered the newly established Harvard Law School, receiving his LL.B. degree in 1820.[2]

Career

He was admitted to the bar in 1821, and went into partnership with Willard Phillips. In addition to his regular work, he edited the American Jurist and published law articles.[3]

Abolitionism

Sewall's ancestor, Samuel Sewall, was one of the first colonial abolitionists. In The Selling of Joseph, he argued that no human being could truly be owned by another; that Africans, like whites, were "the sons and daughters of the first Adam, the brethren and sisters of the last Adam, and the offspring of God," and, as such, "ought to be treated with a respect agreeable."[4]

Samuel E. Sewall's first anti-slavery article, On Slavery in the United States (1827) was more conservative. Although he condemned slavery as a "great national evil,"[5] he scoffed at the idea that slavery should be abolished immediately and all at once: "nothing could be more absurd and dangerous than a sudden enfranchisement of all the negroes."[6]

It was not until he heard William Lloyd Garrison speak that he took up the cause in earnest. With his friends Samuel J. May and A. Bronson Alcott, Sewall attended Garrison's first public lecture in Boston on October 16, 1830. Afterwards, the three of them introduced themselves to Garrison and talked with him late into the night. Garrison convinced him that "immediate, unconditional emancipation was the right of every slave and could not be withheld by his master an hour without sin." Sewall arranged to have Garrison repeat his lecture in a better hall. Later he helped fund the Liberator, Garrison's abolitionist newspaper,[7] and co-founded the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society,[8] joining the Board of Managers in 1832. The two remained friends for many years, despite their very different personalities and frequent disagreements about strategy.[9]

Sewall volunteered his services as a lawyer to the Society, drafting petitions, resolutions, arguments, and legal defenses, as well as preparing annual reports and writing articles for the Liberator. He also enlisted the support of other abolitionists such as Maria Weston Chapman and Ellis Gray Loring.[10] He was a trustee of the short-lived Noyes Academy in New Hampshire, an interracial school which was destroyed by a mob in 1835.[11]

Sewall's abolitionist convictions grew stronger over the years. In 1851 he wrote in a letter to Samuel May:

Much as I abominate bloodshed, I think it far better that two or three slaveholders and their assistant slave-hunters should be killed than that a man should be dragged back into slavery....I cannot blame a man for fighting for his liberty, or anyone else for fighting for him.[12]

Fugitive slave cases

On August 1, 1836, Sewall represented Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates, two refugees from Baltimore who had been held prisoner by the captain of the Chickasaw. Sewall successfully argued that the captain had no right to detain the women, and the judge ordered their release. Immediately the agent for the slaveholder inquired about a warrant for the women's arrest. Fearing that the women were about to be seized, spectators rioted in the courtroom and ushered Small and Bates to safety. The incident came to be known as the Abolition Riot of 1836. Some commentators suspected Sewall of instigating the riot; he received threatening letters and was physically assaulted in his office by a relative of the slaveholder.[13]

Later that month, he and Ellis Gray Loring, with the assistance of Rufus Choate, obtained the release of Med Slater, a six-year-old girl who had traveled to Boston from New Orleans in the service of Mary Aves Slater. The case was originally brought to their attention by Lydia Maria Child and the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Loring and Sewall argued in Commonwealth v. Aves that the Massachusetts constitution banned slavery and that therefore the child was freed as soon as she entered the state.[14] The slaveholders were barred from taking Med back to New Orleans, and she was placed in the custody of a state-appointed guardian.[15] In 1841, Sewall brought a similar case against a Mrs. Taylor, who had brought an eight-year-old boy with her from Arkansas. In another case, that of a girl named Amy who had been brought to Boston from New Orleans, Sewall was unsuccessful; the judge allowed the slaveholder to leave with the child on the grounds that she "appeared happy and contented and was acting under no visible restraint."[14]

Sewall was the lead defender of George and Rebecca Latimer in the fall of 1842, and when he lost the case, he and others purchased Latimer's freedom.[16] In 1848, he joined a litigation team in Washington D.C. that included Francis Jackson, Salmon P. Chase, Samuel Gridley Howe, Horace Mann, and Robert Morris. The group defended Daniel Drayton, the captain charged in the Pearl incident. Although Drayton was convicted, his lawyers succeeded in getting his sentence reduced from twenty years to four.[10]

In 1851, the Boston Vigilance Committee hired Sewall to help with the case of Shadrach Minkins.[17] Together with Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and Richard Henry Dana Jr., Sewall filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus calling for Minkins's release from police custody. When the petition was denied, members of the Boston Vigilance Committee rescued Minkins, who escaped to Canada with help from the Underground Railroad.[18] That same year, Sewall teamed with Wendell Phillips to defend Thomas Sims, a refugee from Savannah, Georgia. It was the first case to challenge the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Despite concerted efforts by Sewall and Phillips, a federal commissioner upheld the law's constitutionality, and Sims was sent back to Georgia.[19]

Following the arrest of Anthony Burns in 1854, Sewall chaired a "Burns meeting" at Faneuil Hall. During the meeting, a small band of abolitionists led by Thomas Wentworth Higginson broke down the courthouse door with a battering ram in an attempt to free Burns. The plan was for hundreds of abolitionists to leave the meeting at the appointed time and help Higginson, but there was a delay of some kind, and by the time they arrived, Higginson and his cohorts had been scattered by the police.[20]

Sewall was not directly involved in the trial of John Brown, but afterwards he and John Albion Andrew prepared an argument in his defense to be used on appeal. The Virginia Supreme Court refused to give them a hearing. Sewall also raised funds for Brown's family. The following year, Sewall and Andrew worked together again in defense of Thaddeus Hyatt, an associate of Brown's. Hyatt was summoned before the U.S. Senate to testify about his dealings with Brown, and was jailed when he refused to testify. Despite the efforts of Sewall and Andrew to get him released, he remained in jail for three months.[21]

State senate term

Sewall was elected to the Massachusetts state senate in 1851 as a Free-Soil candidate. While in office he served as chairman of the judiciary committee. He introduced a bill which he claimed was the shortest ever enacted by the Massachusetts legislature: "Aliens may take, hold, convey, and transmit real estate."[22] He also introduced a number of bills which did not pass, some of which were later used as a basis for bills that did. He proposed to amend the law of evidence to prevent witnesses from being barred from testifying because of their religious beliefs or lack thereof; to make "extreme cruelty and habitual intemperance" grounds for divorce; to abolish capital punishment; to protect the property of married women; and to nullify the Fugitive Slave Law.[23]

When his term was over, he declined to run for reelection. Later, when the Massachusetts personal liberty laws were under attack, he published a series of articles defending them.[24]

Women's rights

Sewall supported equal rights for women. After his death, his widow, Harriet Winslow Sewall, wrote a poem about him titled "The Defender of Women."[25]

One of his clients was a woman who came to him to inquire about a divorce. Afterwards, her husband had her committed to the McLean Asylum, where she was subjected to the abusive practices that were common in such institutions at the time. While on an outing, she dropped a note for Sewall out of the carriage window, asking for his help. The note reached him, and he managed to have her released from the asylum. He then instigated legislative reforms requiring proper classification of patients in mental institutions, allowing patients to communicate with friends, and establishing visiting boards. Years later, another of his ideas was adopted: the addition of women physicians to the staff.[26]

Sewall encouraged women reformers, such as Lucretia Mott and Sarah and Angelina Grimké, who were criticized for speaking in public. He supported Abby Kelley when some members of the American Anti-Slavery Society objected to her taking a prominent role in the group.[27] He supported the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women, and was a director of the New England Female Medical College. Marie Elizabeth Zakrzewska, a pioneering woman physician who headed a department there, later said of Sewall, "He served the cause for the education of medical women when this was so unpopular as to call forth ridicule upon any man who openly avowed it." Sewall's own daughter Lucy eventually became a physician.[28]

Sewall wrote articles defending women's right to hold public office, to serve on juries, and to vote. He was one of the signers of the call for the convention at which the New England Woman Suffrage Association was founded. In 1886, he published a tract titled Legal Condition of Women in Massachusetts.[29] He frequently appeared before the state legislature with Lucy Stone and Henry Browne Blackwell to press for reforms, and sent regular updates to the Woman's Journal. When Massachusetts women were granted the right to vote in school committee elections, he published a pamphlet of instructions for the novice voters.[30]

Personal life and legacy

In the summer of 1835, while attending an anti-slavery conference in New York, Sewall met a Quaker family, Nathan and Comfort Winslow of Portland, Maine, and their daughter Louisa. He married Louisa Winslow in 1836 after persuading her to become a Unitarian.[31] Their first child, Lucy Ellen Sewall, was born in 1837 and went on to become a successful Boston physician. A second daughter, Louisa Winslow Sewall, was born in 1846. The family lived in Roxbury until 1848, when they moved to Melrose, Massachusetts,[8] and later, Norfolk, Massachusetts.[10] Sewall's first wife died in 1850; seven years later he married his late wife's widowed sister, Harriet Winslow List, a poet and editor.[32]

Sewall died of pneumonia on December 20, 1888, aged 89.[33] The poet John Greenleaf Whittier, Sewall's lifelong friend and fellow abolitionist, wrote a poem in his memory.[34]

Selected writings

- "On Slavery in the United States". The Christian Examiner. IV (III): 201–227. May–June 1827.

- "Argument on behalf of Thaddeus Hyatt : brought before the Senate of the United States on a charge of contempt for refusing to appear as a witness before the Harper's Ferry Committee". Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection. Cornell University Library. 1860.

- Legal Condition of Women in Massachusetts in 1886. Boston: Addison C. Getchell. 1886.

Notes

- Snodgrass gives his birth year as 1789; Tiffany, Merrill, and several other sources say 1799.

References

Citations

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 5, 10.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 12-13.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 17

- Sewall (1700), quoted in Tiffany (1898), p. 33.

- Sewall (1827), p. 205.

- Sewall (1827), p. 206.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 36; Snodgrass (2015), p. 478.

- Merrill (1979), p. 219

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 39-41.

- Snodgrass (2015), p. 478.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 43.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 80.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 64-65

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 66-68; Snodgrass (2015), pp. 478, 486.

- "Great American Trials: Commonwealth v. Aves, 1836". Encyclopedia.com. Thomson Learning. 2002.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 70; Snodgrass (2015), p. 478.

- Snodgrass (2015), p. 479.

- "The Ordeal of Shadrach Minkins". The Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 72-77; Snodgrass (2015), p. 479.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 78.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 104-106.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 96.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 97, 100.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 107, 109.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 127.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 128-129.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 130.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 131-133

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 133-138.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 142-143.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 23.

- Tiffany (1898), pp. 31, 83, 90, 118.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 165.

- Tiffany (1898), p. 11.

Bibliography

- Garrison, William Lloyd (1979). Merrill, Walter M. (ed.). The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison: Let the Oppressed Go Free, 1861-1867. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674526655.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). "Sewall, Samuel Edmund (1789-1888)". The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations. Routledge. pp. 478–479. ISBN 9781317454168.

- Tiffany, Nina Moore (1898). Samuel E. Sewall: A Memoir. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. (Nina Moore Tiffany (1852–1958) was the author of several books and an illustrator for historical children's books. Note on Photograph Album of the Moore, Newell, and Tiffany Families.)