San Mateo Mountains (Socorro County, New Mexico)

The San Mateo Mountains are a mountain range in Socorro County, in west-central New Mexico in the southwestern United States. The highest point in the range is West Blue Mountain, at 10,336 ft (3,151 m). The range runs roughly north-south and is about 40 miles (64 km) long. It lies about 25 miles (40 km) north-northwest of the town of Truth or Consequences and about 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Socorro. They should not be confused with the identically named range in Cibola and McKinley counties, north of this range.

Most of the San Mateo Mountains are within the Magdalena Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest. There are two designated wilderness areas in the range, the Apache Kid Wilderness 44,650 acres (181 km2) and the Withington Wilderness 18,869 acres (76 km2). There are three Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRA) within the San Mateos: the Apache Kid Contiguous IRA (67,570 acres), the San Jose IRA (16,957 acres), and the White Cap IRA (8,039).

Geology

The San Mateo Mountains are a fault-block range, made of volcanic rock from the Datil-Mogollon Volcanic Field, of age between twenty-eight and twenty-four million years.[1] They form part of the western edge of the Rio Grande Rift Valley. They also form the eastern border of the Plains of San Agustin, site of the world-renowned Very Large Array.

Significant summits include:[2]

| Mountain | Height (ft) | Height (m) | Coordinates | Prominence (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Blue Mountain | 10,783 | 3,287 | 33.6651°N 107.4457°W | 3,146 |

| Vic's Peak | 10,252 | 3,125 | 33.5531°N 107.4350°W | 1,432 |

| San Mateo Mountain | 10,145 | 3,092 | 33.5604°N 107.4498°W | 652 |

| San Mateo Peak | 10,139 | 3,090 | 33.6112°N 107.4323°W | 1,199 |

| Mount Withington | 10,115 | 3,083 | 33.8807°N 107.4862°W | 2,335 |

| Apache Kid Peak | 10,048 | 3,063 | 33.6414°N 107.4152°W | 539 |

History and Culture

The history of the San Mateo Mountains is intimately linked with the rich history of the surrounding area. Basham noted in his report documenting the archeological history of the Cibola's Magdalena Ranger District that "[t]he heritage resources on the district are diverse and representative of nearly every prominent human evolutionary event known to anthropology. Evidence for human use of district lands date back 14,000 years to the Paleoindian period providing glimpses into the peopling of the New World and megafaunal extinction."[3] Much of the now Magdalena Ranger District were a province of the Apache. Bands of Apache effectively controlled the Magdalena-Datil region from the seventeenth century until they were defeated in the Apache Wars in the late nineteenth century.[3] Outlaw renegades Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch and notorious Apaches like Cochise and Geronimo have ties to the San Mateos. Vic's Peak was named after Victorio, "a Mimbreño Apache leader whose territory included much of the south and southwest New Mexico."[4] Famous for defying relocation orders in 1879 and leading his warriors "on a two-year reign of terror before he was killed," Victorio is at least as highly regarded as Geronimo or Cochise among Apaches.[4] Perhaps most famous outlaw was the Apache Kid whose supposed grave lies within the Apache Kid Wilderness. Stories of depredations by the Apache Kid, and of his demise, became so common and dramatic that in southwestern folklore they may be exceeded only by tales of lost Spanish gold.[3] Native Americans lingered in the San Mateos well into the 1900s. We know this by an essay written by Aldo Leopold in 1919 where he documents stumbling upon the remains of a recently abandoned Indian hunting camp.[5]

- Cultural or Historic Figures with Ties to the San Mateo Mountains

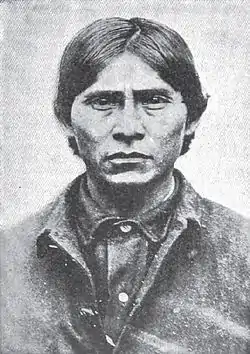

The Apache Kid is the namesake for the Wilderness area in the San Mateos.

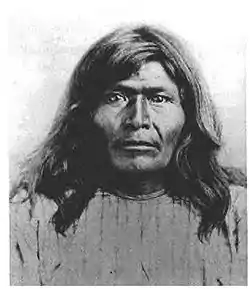

The Apache Kid is the namesake for the Wilderness area in the San Mateos. Vic's Peak in the San Mateo Mountains is named for Victorio, an Apache warrior and chief.

Vic's Peak in the San Mateo Mountains is named for Victorio, an Apache warrior and chief. Geronimo (Goyaałé), a Bedonkohe Apache; kneeling with rifle, 1887.

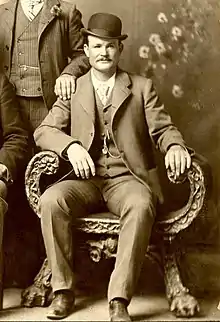

Geronimo (Goyaałé), a Bedonkohe Apache; kneeling with rifle, 1887. Butch Cassidy poses in the Wild Bunch group photo, Fort Worth, Texas, 1901.

Butch Cassidy poses in the Wild Bunch group photo, Fort Worth, Texas, 1901.

A mining rush followed the Apache wars – gold, silver, and copper were found in the mountains. It wasn't until this time that extensive use of the area by non-Native Americans occurred.[6] While some mining activity, involving gold, silver, and copper, occurred in the southern part of the range near the end of the nineteenth century,[1] the prospecting/mining remnants are barely visible today due to collapse, topographic screening, and vegetation regrowth. While miners combed the mountains for mineral riches during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stockmen drove tens of thousands of sheep and cattle to stockyards at the village of Magdalena, then linked by rail with Socorro.[4] In fact, the last regularly used cattle trail in the United States stretched 125 miles westward from Magdalena. The route was formally known as the Magdalena Livestock Driveway, but more popularly known to cowboys and cattlemen as the Beefsteak Trail. The trail began use in 1865 and its peak was in 1919. The trail was used continually until trailing gave way to trucking and the trail official closed in 1971.[3]

Wildlife

The range is home to mountain lion, black bear, elk, mule deer, pronghorn, goshawk, and wild turkey and contains several thousand acres of critical habitat for the threatened Mexican spotted owl. Ponderosa, oak, aspen, spruce, fir, and all three juniper types are found in the San Mateos. The San Mateos were listed in a 2004 report by The Nature Conservancy as a key conservation area due to their ecological diversity and species richness[7] and are important breeding ground for mountain lions.[8]

- Wildlife in the San Mateo Mountains

The San Mateo Mountains contain critical habitat for the threatened Mexican spotted owl.

The San Mateo Mountains contain critical habitat for the threatened Mexican spotted owl. The San Mateos are home to healthy populations of elk.

The San Mateos are home to healthy populations of elk. A black bear in Cibola National Forest.

A black bear in Cibola National Forest. A mule deer fawn in the snow.

A mule deer fawn in the snow.

Recreation

The area provides hiking, camping, backpacking, hunting, horseback-riding, and stargazing opportunities. There are four developed campsites in or near the San Mateos, including the Springtime, Luna Park, Bear Trap, and Hughes Mills campgrounds. One of these campgrounds (Hughes Mills) provides hiking access to the Mt. Withington lookout.

See also

References

- Butterfield, Mike, and Greene, Peter, Mike Butterfield's Guide to the Mountains of New Mexico, New Mexico Magazine Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-937206-88-1

- NM peaks on Lists of John Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Basham, M. (2011). Magdalena Ranger District Background for Survey. US Forest Service.

- Julyan, Robert (2006). The Mountains of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- Leopold, A. (2003). Brown, D. E.; Carmony, N. B. (eds.). Aldo Leopold's Southwest. University of New Mexico Press.

- Ugnade, H.E. (1972). Guide to the New Mexico Mountains. University of New Mexico Press.

- The Nature Conservancy (2004). Chapter 10: Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Cibola National Forest, Mountain Districts in Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3.

- Menke, K. (2008). Locating Potential Cougar (Puma concolor) Corridors in New Mexico Using a Least-Cost Path Corridor GIS Analysis (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15.