Sanfilippo syndrome

Sanfilippo syndrome, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis type III (MPS III), is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease that primarily affects the brain and spinal cord. It is caused by a buildup of large sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans (AKA GAGs, or mucopolysaccharides) in the body's lysosomes.

| Sanfilippo Syndrome (MPS III) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mucopolysaccharidosis III; MPS III |

| |

| 12-year-old girl with Sanfilippo Syndrome Type A | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Progressive intellectual disability; hyperactivity; dementia; loss of mobility |

| Usual onset | Birth; symptoms usually become apparent between ages 2-6 |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Sanfilippo Syndrome Types A, B, C, and D |

| Causes | Inherited enzyme deficiency |

| Diagnostic method | MPS urine screen (initial test), confirmed by blood test |

| Differential diagnosis | Autism spectrum disorder[1] |

| Prognosis | Lifespan is reduced; most patients survive until the early teenage years, but some may reach their 30s |

| Frequency | 1 in 70,000[2] |

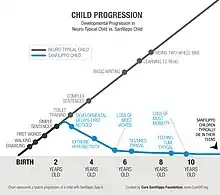

Affected children generally do not show any signs or symptoms at birth. Although some early indicators can be respiratory issues at birth, large head size, and umbilical hernia.[3] In early childhood, they begin to develop developmental disability and loss of previously learned skills. In later stages of the disorder, they may develop seizures and movement disorders. Patients with Sanfilippo syndrome usually live into adolescence or early adulthood.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The disease manifests in young children. Symptoms usually begin to appear between 2 and 6 years of age.[5] Affected infants appear normal, although some mild facial dysmorphism may be noticeable. Of all of the MPS diseases, Sanfilippo syndrome produces the fewest physical abnormalities. After an initial symptom-free interval, patients usually present with a slowing of development and/or behavioral problems, followed by progressive intellectual decline resulting in severe dementia and progressive motor disease.[6] Acquisition of speech is often slow and incomplete.

The disease progresses to increasing behavioral disturbance including temper tantrums, hyperactivity, destructiveness, aggressive behavior, pica, difficulties with toilet training, and sleep disturbance. As affected children initially have normal muscle strength and mobility, the behavioral disturbances may be difficult to manage. The disordered sleep in particular presents a significant problem to care providers.

In the final phase of the illness, children become increasingly immobile and unresponsive, often require wheelchairs, and develop swallowing difficulties and seizures. The life-span of an affected child does not usually extend beyond late teens to early twenties.

Individuals with MPS Type III tend to have mild skeletal abnormalities; osteonecrosis of the femoral head may be present in patients with the severe form. Optic nerve atrophy, deafness, and otitis can be seen in moderate to severe individuals. Other characteristics include coarse facial features, thick lips, synophrys, and stiff joints.

It is difficult to clinically distinguish differences among the four types of Sanfilippo syndrome. However, type A is usually the most severe subtype, characterized by earliest onset, rapid clinical progression with severe symptoms, and short survival.[7] The median age of death for children afflicted with type A is 15.4 years, ±4.1 years.[8]

It is important that simple and treatable conditions such as ear infections and toothaches not be overlooked because of behavior problems that make examination difficult. Children with MPS type III often have an increased tolerance to pain. Bumps, bruises, or ear infections that would be painful for other children often go unnoticed in children with MPS type III. Some children with MPS type III may have a blood-clotting problem during and after surgery.[5]

Genetics

Mutations in four different genes can lead to Sanfilippo Syndrome. This disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. People with two working copies of the gene are unaffected. People with one working copy are genetic carriers of Sanfilippo Syndrome. They have no symptoms but may pass down the defective gene to their children. People with two defective copies will suffer from Sanfilippo Syndrome.[9]

| Sanfilippo Syndrome type | Gene | Enzyme | Chromosomal region | Number of known mutations causing this type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | SGSH | heparan N-sulfatase[9] | 17q25.3 | 137 |

| Type B | NAGLU | Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase[9] | 17q21.2 | 152 |

| Type C | HGSNAT | acetyl-CoA:alpha-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase[9] | 8p11.21 | 64 |

| Type D | GNS | N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase[9] | 12q14.3 | 23 |

Mechanism

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are chains of sugar molecules. They are found in the extracellular matrix and the cell membrane, or stored in the secretory granules. GAGs are stored in the cell lysosome, and are degraded by enzymes such as glycosidases, sulfatases, and acetyltransferases. Deficiency in these enzymes lead to the four subtypes of MPS III.[7]

Diagnosis

Sanfilippo Syndrome Types A, B, C, and D are considered to be clinically indistinguishable, although mutations in different genes are responsible for each disease. The following discussion is therefore applicable to all four conditions.

A urinalysis can show elevated levels of heparan sulfate in the urine.[9] All four types of Sanfilippo syndrome show increased levels of GAGs in the urine; however, this is less true of Sanfilippo syndrome than other MPS disorders. Additionally, urinary GAG levels are higher in infants and toddlers than in older children. In order to avoid a false negative urine test due to dilution, it is important that a urine sample be taken first thing in the morning.

The diagnosis may be confirmed by enzyme assay of skin fibroblasts and white blood cells. The enzyme assay is considered the most-credible diagnostic tool because it detects whether or not the enzymes in the cellular pathway breaking down heparan sulfate is present or not, providing a definitive answer. This test is also ideal for younger patients in which collecting a viable urine sample is difficult or impossible. Another diagnostic tool can be gene sequencing. However, if the genetic mutation they carry has never been seen or recorded, the patient would receive a false negative.

Prenatal diagnosis is possible by chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis.[10]

Treatments

Treatment remains largely supportive. The behavioral disturbances of MPS-III respond poorly to medication. If an early diagnosis is made, bone marrow replacement may be beneficial. Although the missing enzyme can be manufactured and given intravenously, it cannot penetrate the blood–brain barrier and therefore cannot treat the neurological manifestations of the disease. Along with many other lysosomal storage diseases, MPS-III exists as a model of a monogenetic disease involving the central nervous system.

Several promising therapies are in development. The French company Lysogene is conducting a Phase II/III clinical trial of a gene therapy based treatment.[11][12] Other potential therapies include chemical modification of deficient enzymes to allow them to penetrate the blood–brain barrier, stabilisation of abnormal but active enzyme to prevent its degradation, and implantation of stem cells strongly expressing the missing enzyme. For any future treatment to be successful, it must be administered as early as possible. Currently MPS-III is mainly diagnosed clinically, by which stage it is probably too late for any treatment to be very effective. Neonatal screening programs would provide the earliest possible diagnosis.

The flavonoid genistein decreases the accumulation of GAGs.[13] In vitro, animal studies and clinical experiments suggest that the symptoms of the disease may be alleviated by an adequate dose of genistein.[14] Despite its reported beneficial properties, genistein also has toxic side effects.[15]

Several support and research groups have been established to speed the development of new treatments for Sanfilippo syndrome.[16][17][18][19] [20]

Participants in the first-ever Caregiver Preference Study for Sanfilippo Syndrome advocated for clinical trials that shift focus from primary cognitive outcomes to other multisystem endpoints, and perceptions of non-curative therapies revealed a preference for treatment options that stop or slow the disorder progression to maintain the child’s current function to ensure quality of life; thus, parents express high risk tolerance and a desire for broader inclusion criteria for trials.[21]

Prognosis

According to a study of patients with Sanfilippo syndrome, the median life expectancy varies depending on the subtype. In Sanfilippo syndrome type A, the mean age at death (± standard deviation) was 15.22 ± 4.22 years. For Type B, it was 18.91 ± 7.33 years, and for Type C it was 23.43 ± 9.47 years. The mean life expectancy for Type A has increased since the 1970s.[22]

Epidemiology

Incidence of Sanfilippo syndrome varies geographically, with approximately 1 case per 280,000 live births in Northern Ireland,[23] 1 per 66,000 in Australia,[24] and 1 per 50,000 in the Netherlands.[25]

The Australian study estimated the following incidences for each subtype of Sanfilippo syndrome:

| Sanfilippo syndrome type | Approximate incidence | Percentage of cases | Age of onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 in 100,000[24] | 60% | 1.5-4 |

| B | 1 in 200,000[24] | 30% | 1-4 |

| C | 1 in 1,500,000[24] | 4% | 3-7 |

| D | 1 in 1,000,000[24] | 6% | 2-6 |

History

The condition is named after Sylvester Sanfilippo, the pediatrician who first described the disease in 1963.[5][10][26]

Caregiver impact

Caregivers for children with Sanfilippo Syndrome face a unique set of challenges because of the disease's complex nature. There is little understanding among clinicians of the family experience of caring for patients with Sanfilippo and how a caregiver's experiences change and evolve as patients age. The burden and impact on caregivers' quality of life is poorly defined and best-practice guidance for clinicians is lacking.[27]

A best-practice guidance to help clinicians understand the challenges caregivers face was published July 2019 in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases by a group of international clinical advisors with expertise in the care of pediatric patients with Sanfilippo, lysosomal storage disorders, and life as a caregiver to a child with Sanfilippo.[27]

The group reviewed key aspects of caregiver burden associated with Sanfilippo B by identifying and quantifying the nature and impact of the disease on patients and caregivers. Recommendations were based on findings from qualitative and quantitative research.[27]

The article's authors reported that: "Providing care for patients with Sanfilippo B impinges on all aspects of family life, evolving as the patient ages and the disease progresses. Important factors contributing toward caregiver burden include sleep disturbances, impulsive and hyperactive behavior, and communication difficulties...Caregiver burden remained high throughout the life of the patient and, coupled with the physical burden of daily care, had a cumulative impact that generated significant psychological stress."[27]

Additionally, the authors call for changing the narrative associated with Sanfilippo: "The panel agreed that the perceived aggressive behavior of the child may be better described as 'physical impulsiveness' and is often misunderstood by the general public. Importantly, the lack of intentionality of the child’s behavior is recognized and shared by parents and panel members...Parents may seek to protect their child from public scrutiny and avoid situations that many engender criticism of their parenting skills."[27]

Culture

The community of Sanfilippo families, foundations, scientists and researchers, and industry partners and collaborators around the world have dedicated November 16 as World Sanfilippo Awareness Day.[28] [29]

World Sanfilippo Awareness Day is about spreading awareness and sparking conversations globally about Sanfilippo Syndrome. This special day of Awareness is in honor of the children around the world living with Sanfilippo Syndrome today, and those who have passed away. It also honors the families of the children with Sanfilippo Syndrome. Nov. 16, 2019, was the first year observing World Sanfilippo Awareness Day.

See also

References

- Marta Figeiredo. "Autism Symptoms May Be Indicative of Sanfilippo Syndrome, Data Review Finds".

- "Mucopolysaccharidoses Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 15 Nov 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Early Symptoms of Sanfilippo Syndrome". Cure Sanfilippo Foundation.

- "Mucopolysaccharidosis type III". Genetics Home Reference. March 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "A Guide to Understanding MPS III" (PDF). web.archive.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Marlies J. Valstar; Hennie T. Bruggenwirth; Renske Olmer; Ron A. Wevers; Frans W. Verheijen; et al. (September 2010). "Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB may predominantly present with an attenuated clinical phenotype". Inherit Metab Dis. 10.1007/s10545-010-9199-y (6): 759–767. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9199-y. PMC 2992652. PMID 20852935.

- Andrade, F.; Aldámiz-Echevarría, L.; Llarena, M.; Couce, M.L. (2015). "Sanfilippo syndrome: Overall review". Pediatrics International. 57 (3): 331–8. doi:10.1111/ped.12636. PMID 25851924.

- Tardieu, Marc (February 2014). "Intracerebral Administration of Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Serotype rh.10 Carrying Human SGSH and SUMF1 cDNAs in Children with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIA Disease: Results of a Phase I/II Trial". Human Gene Therapy. 25 (6). p. 506–516. doi:10.1089/hum.2013.238.

- Edens Hurst, Anna C.; Zieve, David; Conaway, Brenda (1 May 2017). "Mucopolysaccharidosis type III". United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Defendi, Germaine L. (23 May 2018). "Sanfilippo Syndrome (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III)". Medscape. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Koberstein, Wayne (November 7, 2018). "Lysogene: Mother of Invention". Life Science Leader. United States: VertMarkets.

- Intracerebral Gene Therapy for Sanfilippo Type A Syndrome on clinicaltrials.gov

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2014-01-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Piotrowska, E.; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Barańska, S.; Tylki-Szymańska, A.; Czartoryska, B.; Wegrzyn, A.; Wegrzyn, G. (Jul 2006). "Genistein-mediated inhibition of glycosaminoglycan synthesis as a basis for gene expression-targeted isoflavone therapy for mucopolysaccharidoses". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (7): 846–52. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201623. PMID 16670689.

- Jin, Y.; Wu, H.; Cohen, EM.; Wei, J.; Jin, H.; Prentice, H.; Wu, JY. (Mar 2007). "Genistein and daidzein induce neurotoxicity at high concentrations in primary rat neuronal cultures". J Biomed Sci. 14 (2): 275–84. doi:10.1007/s11373-006-9142-2. PMID 17245525.

- Cure Sanfilippo Foundation, funding research to accelerate discovery of a cure to Sanfilippo Syndrome

- Jonah's Just Begun - Foundation to Cure Sanfilippo, Inc.

- Phoenix Nest, Inc., a biotech company seeking treatments and cures for Sanfilippo Syndrome

- Phunk Phenomenon HipHop For Hope, a dance crew in Boston raising awareness for Sanfilippo Syndrome

- Team Sanfilippo Foundation, a medical research foundation created by parents of children with Sanfilippo Syndrome

- Porter, K.A.; O'Neill, C.; Drake, E.; et al. (December 2020). "Parent Experiences of Sanfilippo Syndrome Impact and Unmet Treatment Needs: A Qualitative Assessment". Neurology and Therapy. 2020.

- Lavery, Christine; Hendriksz, Chris J.; Jones, Simon A. (23 Oct 2017). "Mortality in patients with Sanfilippo syndrome". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 12 (1): 168. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0717-y. PMC 5654004. PMID 29061114.

- Nelson J (December 1997). "Incidence of the mucopolysaccharidoses in Northern Ireland". Hum. Genet. 101 (3): 355–8. doi:10.1007/s004390050641. PMID 9439667. S2CID 23099247.

- Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF (January 1999). "Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders". JAMA. 281 (3): 249–54. doi:10.1001/jama.281.3.249. PMID 9918480.

- Poorthuis BJ, Wevers RA, Kleijer WJ, et al. (1999). "The frequency of lysosomal storage diseases in The Netherlands". Hum. Genet. 105 (1–2): 151–6. doi:10.1007/s004390051078. PMID 10480370.

- Sanfilippo, S. J.; Podosin, R.; Langer, L. O., Jr.; Good, R. A. : Mental retardation associated with acid mucopolysacchariduria (heparitin sulfate type). J. Pediat. 63: 837-838, 1963.

- Shapiro, Elsa; Lourenço, Charles Marques; Mungan, Neslihan Onenli; Muschol, Nicole; O’Neill, Cara; Vijayaraghavan, Suresh (8 July 2019). "Analysis of the caregiver burden associated with Sanfilippo syndrome type B: panel recommendations based on qualitative and quantitative data". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 14 (1): 168. doi:10.1186/s13023-019-1150-1. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 6615275. PMID 31287005.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - [Awareness Days - International Calendar] https://www.awarenessdays.com/awareness-days-calendar/world-sanfilippo-awareness-day-2019/

- [World Sanfilippo Awareness Day] https://curesanfilippofoundation.org/worldsanfilippoawarenessday/

External links

Media related to Sanfilippo syndrome at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sanfilippo syndrome at Wikimedia Commons

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |