Santa Ana winds

The Santa Ana winds are strong, extremely dry downslope winds that originate inland and affect coastal Southern California and northern Baja California. They originate from cool, dry high-pressure air masses in the Great Basin.

Santa Ana winds are known for the hot, dry weather that they bring in autumn (often the hottest of the year), but they can also arise at other times of the year.[1] They often bring the lowest relative humidities of the year to coastal Southern California. These low humidities, combined with the warm, compressionally-heated air mass, plus high wind speeds, create critical fire weather conditions. Also sometimes called "devil winds",[2][3] the Santa Anas are infamous for fanning regional wildfires.

Description

Meteorology

The National Weather Service defines Santa Ana winds as "Strong down slope winds that blow through the mountain passes in southern California. These winds, which can easily exceed 40 miles per hour (64 km/h), are warm and dry and can severely exacerbate brush or forest fires, especially under drought conditions."[4]

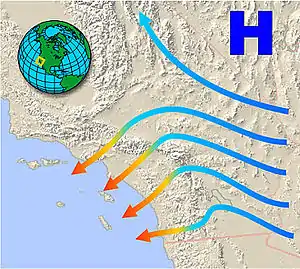

The Santa Anas are katabatic winds—Greek for "flowing downhill", arising in higher altitudes and blowing down towards sea level.[5] Santa Ana winds originate from high-pressure airmasses over the Great Basin and upper Mojave Desert. Any low-pressure area over the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of California, can change the stability of the Great Basin High, causing a pressure gradient that turns the synoptic scale winds southward down the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada and into the Southern California region.[6] Warm, dry air flows outward in a clockwise spiral from the high pressure center. This dry airmass sweeps across the deserts of eastern California toward the coast, and encounters the towering Transverse Ranges, which separate coastal Southern California from the deserts. The airmass, flowing from high pressure in the Great Basin to a low pressure center off the coast, takes the path of least resistance by channeling through the mountain passes to the lower coastal elevations, as the low pressure area off the coast pulls the airmass offshore.[7]

These passes include the Soledad Pass, the Cajon Pass, and the San Gorgonio Pass, all well known for exaggerating Santa Anas as they are funneled through.[8] As the wind narrows and is compressed into the passes its velocity increases dramatically, often to near-gale force or above. At the same time, as the air descends from higher elevation to lower, the temperature and barometric pressure increase adiabatically, warming about 5 °F for each 1,000 feet it descends (1 °C for each 100 m).[8] Relative humidity decreases with the increasing temperature. The air has already been dried by orographic lift before reaching the Great Basin, as well as by subsidence from the upper atmosphere, so this additional warming often causes relative humidity to fall below 10 percent.[9] The end result is a strong, warm, and very dry wind blowing out of the bottom of mountain passes into the valleys and coastal plain.

During Santa Ana conditions it is typically hotter along the coast than in the deserts,[10] with the Southern California coastal region reaching some of its highest annual temperatures in autumn rather than summer.

Frigid, dry arctic air from Canada tends to create the most intense Santa Ana winds.[11]

While the Santa Anas are katabatic, they are not Föhn winds. These result from precipitation on the windward side of a mountain range which releases latent heat into the atmosphere which is then warmer on the leeward side (e.g., the Chinook or the original Föhn).

If the Santa Anas are strong, the usual day-time sea breeze may not arise, or develop weak later in the day because the strong offshore desert winds oppose the on-shore sea breeze. At night, the Santa Ana Winds merge with the land breeze blowing from land to sea and strengthen because the inland desert cools more than the ocean due to differences in the heat capacity and because there is no competing sea breeze.[9][12]

Regional impacts

Santa Ana winds often bring the lowest relative humidities of the year to coastal Southern California. These low humidities, combined with the warm, compressionally-heated air mass, plus the high wind speeds, create critical fire weather conditions. The combination of wind, heat, and dryness accompanying the Santa Ana winds turns the chaparral into explosive fuel feeding the infamous wildfires for which the region is known. Wildfires fanned by Santa Ana winds burned 721,791 acres (292,098 ha) in two weeks during October 2003,[13] and another 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) in the October 2007 California wildfires.[14]

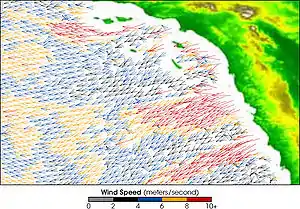

Although the winds often have a destructive nature, they have some benefits as well. They cause cold water to rise from below the surface layer of the ocean, bringing with it many nutrients that ultimately benefit local fisheries. As the winds blow over the ocean, sea surface temperatures drop about 4°C (7°F), indicating the upwelling. Chlorophyll concentrations in the surface water go from negligible, in the absence of winds, to very active at more than 1.5 milligrams per cubic meter in the presence of the winds.

Local maritime impacts

During the Santa Ana winds, large ocean waves can develop. These waves come from a northeasterly direction; toward the normally sheltered side of Catalina Island. Protected harbors such as Avalon and Two Harbors are normally sheltered and the waters within the harbors are very calm. In strong Santa Ana conditions, these harbors develop high surf and strong winds that can tear boats from their moorings and crash them onto the shore. During a Santa Ana, it is advised that boaters moor on the back side of the island to avoid the dangerous conditions of the front side.

Related phenomena

Santa Ana fog

A Santa Ana fog is a derivative phenomenon in which a ground fog settles in coastal Southern California at the end of a Santa Ana wind episode. When Santa Ana conditions prevail, with winds in the lower two to three kilometers (1.25-1.8 miles) of the atmosphere from the north through east, the air over the coastal basin is extremely dry, and this dry air extends out over offshore waters of the Pacific Ocean. When the Santa Ana winds cease, the cool and moist marine layer may re-form rapidly over the ocean if conditions are right. The air in the marine layer becomes very moist and very low clouds or fog occurs.[15][16] If wind gradients turn on-shore with enough strength, this sea fog is blown onto the coastal areas. This marks a sudden and surprising transition from the hot, dry Santa Ana conditions to cool, moist, and gray marine weather, as the Santa Ana fog can blow onshore and envelop cities in as quickly as fifteen minutes. However, a true Santa Ana fog is rare, because it requires conditions conducive to rapid re-forming of the marine layer, plus a rapid and strong reversal in wind gradients from off-shore to on-shore winds. More often, the high pressure system over the Great Basin, which caused the Santa Ana conditions in the first place, is slow to weaken or move east across the United States. In this more usual case, the Santa Ana winds cease, but warm, dry conditions under a stationary air mass continue for days or even weeks after the Santa Ana wind event ends.

A related phenomenon occurs when the Santa Ana condition is present but weak, allowing hot dry air to accumulate in the inland valleys that may not push all the way to sea level. Under these conditions auto commuters can drive from the San Fernando Valley where conditions are sunny and warm, over the low Santa Monica Mountains, to plunge into the cool cloudy air, low clouds, and fog characteristic of the marine air mass. This and the "Santa Ana fog" above constitute examples of an air inversion.

Sundowner winds

The similar winds in the Santa Barbara and Goleta coast area occur most frequently in the late spring to early summer, and are strongest at sunset, or "sundown"; hence their name: sundowner. Because high pressure areas usually migrate east, changing the pressure gradient in southern California to the northeast, it is common for "sundowner" wind events to precede Santa Ana events by a day or two.[17]

Arctic and Antarctic katabatic winds

Winds blowing off the elevated glaciated plateaus of Greenland and Antarctica experience the most extreme form of katabatic wind, of which the Santa Ana is a type, for the most part. The winds start at a high elevation and flow outward and downslope, attaining hurricane gusts in valleys, along the shore, and even out to sea. Like the Santa Ana, these winds also heat up by compression and lose humidity, but because they start out so extraordinarily cold and dry and blow over snow and ice all the way to the sea, the perceived similarity is negligible.

Historical impact

The Santa Ana winds and the accompanying raging wildfires have been a part of the ecosystem of the Los Angeles Basin for over 5,000 years, dating back to the earliest habitation of the region by the Tongva and Tataviam peoples.[18]

The Santa Ana winds have been recognized and reported in English-language records as a weather phenomenon in Southern California since at least the mid-nineteenth century.[2] Various episodes of hot, dry winds have been described over this history as dust storms, hurricane-force winds, and violent north-easters, damaging houses and destroying fruit orchards. Newspaper archives have many photographs of regional damage dating back to the beginnings of news reporting in Los Angeles. When the Los Angeles Basin was primarily an agricultural region, the winds were feared particularly by farmers for their potential to destroy crops.[2]

The winds are also associated with some of the area's largest and deadliest wildfires, including some of the state's largest and deadliest fires on record, the Camp fire, Thomas Fire, and Cedar Fire, as well as the Laguna Fire, Old Fire, Esperanza Fire, Santiago Canyon Fire of 1889 and the Witch Creek Fire.

In October 2007, the winds fueled major wild fires and house burnings in Escondido, Malibu, Rainbow, San Marcos, Carlsbad, Rancho Bernardo, Poway, Ramona, and in the major cities of San Bernardino, San Diego and Los Angeles. The Santa Ana winds were also a factor in the November 2008 California wildfires.

In early December 2011, the Santa Ana winds were the strongest yet recorded. An atmospheric set-up occurred that allowed the towns of Pasadena and Altadena in the San Gabriel Valley to get whipped by sustained winds at 97 mph (156 km/h), and gusts up to 167 mph (269 km/h).[19] The winds toppled thousands of trees, knocking out power for over a week. Schools were closed, and a "state of emergency" was declared. The winds grounded planes at LAX, destroyed homes, and were even strong enough to snap a concrete stop light from its foundation.[20] The winds also ripped through Mammoth Mountain and parts of Utah. Mammoth Mountain experienced a near-record wind gust of 175 mph (282 km/h), on December 1, 2011.[19]

In May 2014, the Santa Ana winds initiated the May 2014 San Diego County wildfires, approximately four months after the Colby Fire in northern Los Angeles County.

In December 2017, a cluster of twenty-five Southern California wildfires were exacerbated by long-lasting and strong Santa Ana winds.

In September 2020, a group of wildfires in Southern California were exacerbated by a mild Santa Ana event, including the Valley Fire, El Dorado Fire, and Bobcat Fire.

In October 2020, the Silverado Fire (Irvine, California) was exacerbated by severe Santa Ana winds.[21]

Health effects

Santa Ana winds are widely believed to affect people's moods and behavior.[22][23][24]

The winds carry Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii spores into nonendemic areas,[25][26] a pathogenic fungus that causes Coccidioidomycosis ("Valley Fever"). Symptomatic infection (40 percent of cases) usually presents as an influenza-like illness with fever, cough, headaches, rash, and myalgia (muscle pain).[27] Serious complications include severe pneumonia, lung nodules, and disseminated disease, where the fungus spreads throughout the body. The disseminated form of Coccidioidomycosis can devastate the body, causing skin ulcers, abscesses, bone lesions, severe joint pain, heart inflammation, urinary tract problems, meningitis, and often death.[28]

Etymology

The most well-accepted explanation for the name Santa Ana winds is that it is derived from the Santa Ana Canyon in Orange County, one of the many locations the winds blow intensely.[2][5] Newspaper references to the name Santa Ana winds date as far back as 1882.[29]

By 1893, controversy had broken out over whether this name was a corruption of the Spanish term Santana (a running together of the words Santa Ana), or the different term Satanás, meaning Satan. However, newspaper mention of the term "Satanás" in reference to the winds did not begin appearing until more than 60 years later. A possible explanation is that the spoken Spanish language merges two identical vowels in elision, when one ends a word and the other begins the next word. Thus the Spanish pronunciation of the phrase "Santa Ana" sounds like "Santana".

Another attempt at explanation of the name claims that it derives from a Native American term for "devil wind" that was altered by the Spanish into the form "Satanás" (meaning Satan), and then later corrupted into "Santa Ana". However, an authority on Native American language claims this term "Santana" never existed in that tongue.[5]

Another derivation favored by the late well-known KABC television meteorologist, Dr. George Fischbeck, cited the etymology of the Santana winds as coming from the early Mexicano/Angeleno: "Caliente aliento de Satanás" or "hot breath of Satan". This is likely a false etymology or folk etymology, though.

In popular culture

The Santa Ana winds are commonly portrayed in fiction as being responsible for a tense, uneasy, wrathful mood among Angelenos. Some of the more well-known literary references include the Philip Marlowe story "Red Wind" by Raymond Chandler, and Joan Didion's Slouching Towards Bethlehem.[2][3]

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands' necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.

— Raymond Chandler, "Red Wind"

The baby frets. The maid sulks. I rekindle a waning argument with the telephone company, then cut my losses and lie down, given over to whatever is in the air. To live with the Santa Ana is to accept, consciously or unconsciously, a deeply mechanistic view of human behavior. ...[T]he violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.

The Santa Ana winds are personified in The CW musical series Crazy Ex-Girlfriend as a prankster narrator responsible for main characters and enemies Rebecca and Nathaniel kissing for the first time. A song titled 'Santa Ana Winds' is sung in a doo-wop style, which educates the viewer on the winds itself. The winds are portrayed by Eric Michael Roy.[30]

The winds are also referenced in Ben Lee’s single 'Catch My Disease', Steely Dan's single 'Babylon Sisters', in the Belinda Carlisle song 'Summer Rain', in the book White Oleander and the film of the same name, in The Beach Boys song Santa Ana Winds, and in the Randy Newman song 'I Love L.A.' and the Nancy Meyers movie The Holiday.

See also

References

- Smith, Joshua Emerson (January 31, 2019). "Climate change should tamp down California's wildfire-fanning Santa Ana winds, study finds". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Masters, Nathan (October 25, 2012). "SoCal's Devil Winds: The Santa Anas in Historical Photos and Literature". www.kcet.org. KCET. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012. "(White)Scholars who have looked into the name's origins generally agree that it derives from Santa Ana Canyon, the portal where the Santa Ana River -- as well as a congested Riverside (CA-91) Freeway -- leaves Riverside County and enters Orange County. When the Santa Anas blow, winds can reach exceptional speeds in this narrow gap between the Puente Hills and Santa Ana Mountains."

- Needham, John (March 12, 1988). "The Devil Winds Made Me Do It : Santa Anas Are Enough to Make Anyone's Hair Stand on End". www.latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- "Santa Ana Wind". NOAA's National Weather Service Glossary. NOAA National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- Fovell, Robert. "UCLA explains the naming of the Santa Ana winds". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on May 6, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Santa Ana". cnap.ucsd.edu. California Nevada Applications Program / California Climate Change Center. October 3, 2015. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- Lin II, Rong-Gong; Duginski, Paul (2019-10-25). "Two destructive fires. Hundreds of miles apart. One culprit: Winds". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- "What are the Santana or Santa Ana Winds?". www.laalmanac.com. Los Angeles Almanac. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- Fovell. "The Santa Ana Winds". UCLA. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- "Santa Ana Winds - Wildfires". NOAA Watch All Hazards Monitor. NOAA National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- Duginski, Paul (2019-10-29). "Why Santa Ana winds later this week may be the strongest of the season thus far". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- Leneman, Mike (2015). "Devil winds: Santa Ana Winds explained by one of us". The Mariner. Pat Reynolds. Nov 2015 (153): 8–9. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

-

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fire deaths, damage come into focus as evacuees cope Archived 2007-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Leipper, D. F., Fog development at San Diego, California, J. Mar. Research, 7, 337-346, 1948.

- Leipper, D. F., Fog on the United States West Coast: a review. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 75, 229-240.

- Ryan, G., and L. E. Burch, 1992: An analysis of sundowner winds: A California downslope wind event. Preprints, Sixth Conf. on Mountain Meteorology, Portland, OR, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 64-67.

- Rutten, Tim (October 15, 2000). "L.A., land of fire -- always". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- Christopher C. Burt (4 December 2011). "Big Winds in the West, Possible Wind Gust Record in California". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-11-13. Retrieved 2017-02-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Andrew Freedman, Diana Leonard (October 27, 2020). "California wildfires: Orange County evacuations grow as blazes spread from strong, dry winds". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- Studying the Dust Kicked up by the Santa Anas Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- NEEDHAM, JOHN (12 March 1988). "The Devil Winds Made Me Do It : Santa Anas Are Enough to Make Anyone's Hair Stand on End". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS" (PDF). Department of Public Health. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- Lawrence L. Schmelzer, M.P.H.; Irving R. Tabershaw, M.D., F.A.P.H.A. (1968). Exposure Factors In Occupational Coccidioidomycosis. McGraw Hill. p. 110.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 680–83. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Coccidioidomycosis". Merck. Archived from the original on 2010-11-14. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- Fovell, Robert (January 2008), Etymology of the name "Santa Ana winds", as revealed in the archives of the Los Angeles Times newspaper, retrieved 2020-09-06

- Shoemaker, Allison. "The Santa Ana winds blow through Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and things get weird". TV Club. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

External links

- University of California, Los Angeles, Meteorology Dept.: Santa Ana Winds

- What are the Santana or Santa Ana Winds?

- "NASA Satellite Finds Something Fishy About Santa Ana Winds". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. March 11, 2004. Retrieved 2006-05-25.

- University of California, San Diego, Meteorology Dept. Santa Anas (includes indicator if there are currently Santa Ana conditions)