Saturnino Herrán

Saturnino Herrán Guinchard (July 9, 1887 – October 8, 1918) was a Mexican painter influential to Latin culture in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Saturnino Herrán | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Self portrait, charcoal sketch, c. 1918 | |

| Born | Saturnino Herrán Guinchard July 9, 1887 |

| Died | October 8, 1918 (aged 31) |

| Nationality | Mexican, Swiss |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | The Offering (1913), Our Gods (1918) |

| Movement | Mexican muralism |

| Signature | |

Biography

Born a mix of Indigenous Mexican and Swiss descent, Saturnine Herrán was raised in Aguascalientes, a city in North-Central Mexico ingrained with Spanish culture. His father owned "the only bookstore in the city and was a professor of bookkeeping at The Academy of Science".[1] At the age of ten, he was exceptional in drawing, painting, and draftsmanship. In 1903, when he was sixteen, his father died. Two years later, the family moved to Mexico City where he studied painting further and began to teach.

At 25 years old, he met Rosario Arellano, his future wife, who occasionally acted as a figure model for pieces like Mujer en Tehuantepec (1914). At the height of his career in 1914, they were married. There is little that is known about their marriage other than it appeared to be "congruent" and "enlightened".[2] Together they had one son, José Francisco.

Herrán completed majestic paintings of Mexican Indigenous people, giving them heroic strength, beauty, and dignity. In 1910 he participated in the exhibition commemorating the Centennial Anniversary of Mexico's Independence. A desire to be a mural painter appeared during his career, and in 1911 he completed commissioned large-scale, mural-like paintings.

He died suddenly in Mexico City on October 8, 1918 at the age of 31 from a gastric complication.

Early career

In 1901 Herrán began taking drawing lessons at the Aguascalientes Academy of Science where his father worked. José Inés Tovilla and Severo Amador[3] helped teach him both drawing and painting. In 1903, his father died. He and his mother moved to Mexico City, where he worked at a telegraph office to support her and took classes from Julio Ruelas at the Academy of San Carlos.[4] He then studied draughtsmanship under Antonio Fabres, a Catalan painter and color under German colorist Gedovious. His work was highly inspired by European theories of modern art including Greek and Roman aesthetics and a high degree of naturalism. He was an "outstanding student" receiving "honorable mentions" in multiple courses.[3] Herrán immersed himself in Mexican art, mixing that with his training in academic European technique, for he saw art as a spiritual experience.

His first paintings displayed figures as allegories of nature and included Spanish mythology and scenes of everyday people at work who were either exhausted or optimistic. By 1908 he gained success and recognition within the artistic community and began winning awards on top of scholarships. In 1909 he became a professor drawing at the National Institute of Fine Arts, where his pupils were Diego Rivera and Roberto Montenegro. In 1910, he turned down a scholarship to study in Europe and took a job as a draftsman in the Department for the Inspection of Archeological Monuments.[3]

1910 launched Herrán into greater success when he participated in the Centennial Anniversary of Mexico's Independence. With fellow artist Jose Orozco, he formed the Society of Mexican Painters and Sculptors and staged a counter-exhibition to the Centennial Anniversary that included art that was purely Mexican. It included his triptych The Legend of the Volcanoes. Herrán's pieces were associated with the work of Velázquez and José de Rivera, with his own influence from Catalan modernism. The exhibition was so popular that the entrance had to be controlled by police. This exhibition made an impression on José Vasconcelos, the future Secretary of Education of Mexico after it was revolutionized. After seeing the exhibition, he commissioned Herrán to do a large-scale mural in the School of Arts and Crafts in 1911.[4]

Mexican modernism

On top of being a professor, Herrán was an activist for modern art, a muralist, book illustrator, draughtsman, and stain glass colorist. While his work had influence from Mexico, Spain, and Catalan it did not fully break away from the traditional European style he was trained to paint in. Herrán, being of mixed descent himself, recognized the multitude of races Mexico embodied, and painted people in natural habitats, capturing their strength, dignity, and inherent beauty. This realization was a part of a movement called 'indigenismo'-a movement that called for social elevation, for a developed personal identity that is inextricably linked to a plethora of Latin races. His generation marked him as one of the painters that "embodied the nations soul" [5]

The Offering (1913) exemplifies Mexican modernism with its allegorical allusion to life's journey. It displays a punt boat in a canal filled with zempasúchitl flowers (a marigold[6] that is traditionally associated with death). Featured are a baby, a youthful man, and an elderly man offering the flowers for the dead. This is a reference to ofrenda, a tradition deeply connected to Mexico's Dia de los Muertos, a celebration of ancestry that is said to connect the living to the dead. Each character is represents a different stage of life, but they are all following the same end destination and respecting their course. When Herran died, his widowed wife requested The Offering yet it was taken to the National Fine Arts Institute. Herrán's works gave credence to the "spiritual beauty of the native people of Mexico in exquisite drawings of Indians whose languid silhouettes stand out against freely interpreted backgrounds of Pre-Columbian sculpture." [5] See: The Shawl (1916) and Criolla with Mantilla (1917–1918).

Later career: muralist

By this time in his career, Saturnino finally became a muralist. "Mural art would be, by definition, revolutionary and Marxist, nationalist and indigenous. In this art, in rather Manichean fashion, the forces of good (those mentioned) confront the forces of evil, represented by Spain, Catholicism, and the Conquistadores and, in modern times, capitalism"[7] These ideologies were painted by fellow artists Orozco and Rivera, making them illustrious in the art world. As mentioned above, he went on to create commissioned murals for the School of Arts and Crafts. His works were used as model for future muralists throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

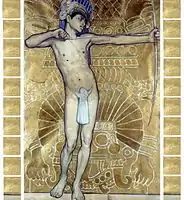

In Herrán's famous triptych Our Gods (1914-1918), he displayed legendary Aztec goddess Coatlicue, who, according to legend, gave birth to the sun, moon, stars. It was commissioned for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. The mural is sixteen feet tall with multiple panels. Latin and Caucasian races are showcased on both sides, yet it draws the eyes of the viewer in to engage with the center panel, Coatlicue Transformed. Jesus Christ, God of the early Christians is in the center of the goddess. Hands, hearts, skulls and crosses are displayed along with lilies, which are representative of Christian spirituality. The piece is a fusion of both cultures as all races on both sides are turned worshiping one god-like figure with one Aztec and one European reference to a higher power. Christ and Coatlicue coalesce in "a vivid expression of his theme concerning the mixture of the two races" [5] Our Gods is arguably Herrán's greatest, most infamous work due to its deep calling to the viewer to accept others, think spiritually, and unify two cultures. It was never fully completed as he worked on it until the day he died. Due to his clear skill with draughtsmanship, some of Herrán's contemporaries criticized his style, calling his paintings "painted drawings" or "effeminate", yet others believe his "superb draftsmanship of the human figure [provided] the strength of his best work".[8]

Legacy

Saturnino paved the way for artists like Orozco and Rivera by creating masterpieces with deep, relatable meaning. Stylistically, he painted his strengths and used well-cultured techniques from years of learning with Spanish, European, and Catalan influence. Herran used free brushwork over his drawings to capture vibrations of light . He blurred certain background colors together to create ambiance. He preferred strong contours, dynamic imagery, and color balanced. "The refinement of Herran's draughtsmanship and use of colour balances the naturalistic imagery in these works combining drawing with watercolour, a technique adapted from Spanish painters such as Néstor de la Torre".[5] Along with integrating well- developed techniques, his work displays a deep knowledge of the human psyche. His art links eminence and dignity to Mexican heritage. It has brought deep meaning to teaching the value of cultural acceptance and gives insight into the brevity of human life for every viewer to relate to.

Major works

- The Offering, 1913

- The Orange Seller, 1913

- Mujer en Tehuantepec 1914

- Nuestros Dioses, 1916

- Woman with the Shawl 1916

- Mujer con Calabaza, 1917

- Our Gods (Cuatlicule Transformed), 1918

Gallery

La Cosecha, 1909

La Cosecha, 1909 The Offering, 1913

The Offering, 1913.jpg.webp) Mujer en Tehuantepec, 1914

Mujer en Tehuantepec, 1914 Nuestros Dioses Antiguos, 1916

Nuestros Dioses Antiguos, 1916 Flechador, 1917

Flechador, 1917.jpg.webp) Mujer con Calabaza, 1917

Mujer con Calabaza, 1917%252C_de_Saturnino_Herr%C3%A1n_en_el_Museo_Aguascalientes_04.jpg.webp) Our Gods, 1918

Our Gods, 1918

References

- "Saturnino Herran: A Bright Light Too Soon Extinguished : Mexico Culture & Arts". www.mexconnect.com. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Bleys, Ruby, C. (2000). Images of Ambiente: Homosexuality and Latin American Art, 1810-Today. Wellington House, London: Continuum. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-8264-4723-6.

- "Saturnino Herrán - Google Arts & Culture". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- "Saturnino Herran - Artist Biography for Saturnino Herran". www.askart.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Oxford Art Online: Saturnino Herran". Oxford Art. November 2017.

- marigold

- University, Cambridge (1995). The Cambridge History of Latin America Volume X: Latin America Since 1930: Ideas, Culture, and Society. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 398–399. ISBN 0 521 49594 6.

- Pomade, Rita (September 1, 2008). "A Bright Light Too Soon Extinguished". Mex Connect. Retrieved November 20, 2017.