Schulpflicht

The (Allgemeine) Schulpflicht (English: (General) School Mandatory) is a statutory regulation in Germany that obliges children and adolescents up to a certain age (depending on the federal state) or up to the completion of a school career to attend a school. The Schulpflicht includes not only regular and punctual school attendance, but also participation in lessons and other school events, as well as doing homework.[2]

Simple laws, the so-called Schulgesetze (school laws), regulate the implementation. The police are often used in this process.[3][4][5] Children whose parents refuse to have them vaccinated must also go to school.[6]

It is one of the very few compulsory school attendance laws in a non-dictatorial country,[7] since most developed countries have compulsory education laws, meaning that education may also take place independent from school, as recorded in the article Homeschooling international status and statistics. Its justification, alleged benefits and motivations are disputed and controversially discussed.

History

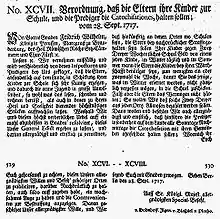

In 1919, the Weimar Constitution stipulated the Schulpflicht for all of Germany,[8] from 1938 to 1945 the Schulpflicht im Deutschen Reich, abbreviated as the Reichsschulpflichtgesetz, was in effect. This law classified people with complex disabilities as unfit for education. For the disabled, compulsory schooling was not introduced until 1978, regardless of the type and intensity of the disability.[9]

Initially, the Schulpflicht applied only to children with German citizenship. It was extended to foreign-born children in the 1960s. For asylum seeker children in North Rhine-Westphalia for example, it was introduced in 2005. Previously, there had been at most a right to attend school.

Positions

Advocacy

The Schulpflicht serves to enforce the state's educational mandate. This mandate is also officially aimed at educating the students as future citizens. The Federal Constitutional Court ruled that schools are better suited than other ways of education for this purpose, as they claim that „Kontakte mit der Gesellschaft und den in ihr vertretenen unterschiedlichen Auffassungen nicht nur gelegentlich stattfinden, sondern Teil einer mit dem regelmäßigen Schulbesuch verbundenen Alltagserfahrung sind“ ("contacts with society and the different views represented in it do not only take place occasionally, but are part of an everyday experience associated with regular school attendance").[10]

The Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb) argues for the Schulpflicht that „Die Allgemeinheit hat ein berechtigtes Interesse daran, der Entstehung von religiös oder weltanschaulich motivierten, Parallelgesellschaften' entgegenzuwirken und Minderheiten zu integrieren [...]“ ("The general public has a legitimate interest in counteracting the emergence of religiously or ideologically motivated 'parallel societies' and in integrating minorities [...]") and claims that „Unsere Gesellschaften sind [...] nur möglich, weil es Schulen gibt, die allen Kindern die notwendigen Voraussetzungen für die Kommunikation vermitteln, das heißt sowohl Kulturtechniken als auch die Orientierung an kulturellen Normen und Werten“ ("Our societies are [...] only possible because there are schools that provide all children with the necessary prerequisites for communication, that is, both cultural techniques and an orientation towards cultural norms and values").[11] In addition, they claim that homeschooling is „[...] von radikalen bibelgläubigen christlichen Eltern gefordert [...]“ ("[...] demanded by radical bible-believing Christian parents [...]").[12] The bpb also thinks that the Schulpflicht does not just mean that all children have to go to school, but also that all children have the right to attend school,[13] although this would not require compulsory schooling, which is why some people see this as a misappropriation of the word.[14] They claim that this is one of the children's rights,[13] although the children's rights education do not state that school attendance is mandatory.

The then CSU chairman Erwin Huber justified the Schulpflicht in September 2008 with the following explanation:[15]

Die allgemeine Schulpflicht gilt als eine unverzichtbare Bedingung für die Gewährleistung der freiheitlichen demokratischen Grundordnung und zugleich als unerlässliche Voraussetzung für die Sicherung der wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Wohlfahrt der Gesellschaft. Sinn und Zweck der Schulpflicht ist nicht nur die Vermittlung von Lehrplaninhalten, sondern insbesondere auch die Schulung der Sozialkompetenz der Kinder. Die Sozialkompetenz wird durch das Lernen in der Klassengemeinschaft und durch gemeinsame Schulveranstaltungen in besonderem Maße gefördert. Neben der Förderung der Sozialkompetenz hat die Schule auch die Funktion, während der Unterrichtszeit auf das Kindeswohl zu achten. Würde man Ausnahmen von der Schulpflicht zulassen, müsste diese Aufgabe von den Jugendämtern übernommen werden. Die Bayerische Verfassung will mit der allgemeinen Schulpflicht alle Kinder und Jugendlichen gleichermaßen und umfassend in die Gesellschaft eingliedern. Dies ist eine der großen emanzipatorischen und demokratischen Entwicklungen des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Criticism

The Schulpflicht has been constantly criticized by various sides until today.[1][16][17]

Some find that it violates article 26 (3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[16] which states: "Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children."[18] and the freedom of assembly.[19] Some people also see the Schulpflicht as a form of deprivation of liberty.[20]

The UN special rapporteur on the right to education, Vernor Muñoz, expressed concern in his report published in Berlin on February 21, 2006 that the restrictive German compulsory education criminalizes the use of the right to education through alternative forms of learning such as homeschooling.[21] University President Dieter Lenzen criticizes that Germany, unlike seven other European countries and the US, adheres to a rigid school attendance requirement instead of leaving it to the parents to decide how and through whom the children learn the subject matter.[22]

In particular, the way the authorities deal with school-age mentally or physically handicapped people and efforts to include people are criticized in Germany, since the said group is also fundamentally obliged to attend school in Germany.[1]

School refusal from Germany, who wanted to teach their children themselves, argued at an immigration court in the USA that the common practice in Germany of refusing parents permission to study at home as a substitute for schooling was political persecution. While in 2010 the immigration court followed the arguments of the school refusal,[23] the Board of Immigration Appeals rejected the family's application in May 2013 on the grounds that US immigration laws did not guarantee automatic right to stay for all people who were in another state and experienced restrictions that would not exist under the American constitution.[24][25]

German philosopher and author Bertrand Stern sees it as a fundamental human right to be able to educate oneself freely (independent from an institution), which is violated by compulsory schooling and criticizes the schooling ideology in his books and publications,[26] which he describes as „inhuman“ ("inhuman"), „verfassungswidrig“ ("unconstitutional") and „obsolet“ ("obsolete") and has „[...] überhaupt keinen Platz mehr in unserer Wirklichkeit“ "[...] no longer any place in our reality".[27] He thinks that the Schulpflicht will be abolished very soon.[28]

German neorobiologist and author Gerald Hüther criticizes that the Schulpflicht degrades children as self-determined subjects to incapacitated objects of schooling.[29] In his opinion, school should be a place that invites as many children as possible and motivates them to go there voluntarily and enthusiastically.[29] He thinks that it is „[...] das Furchtbarste, das einem überhaupt passieren kann [...]“ ("[...] the most terrible thing that can ever happen to you [...]" if you ask young people why they go to school and their only answer is „Weil ich muss“ ("Because I have to") and that children want to learn naturally when they are born.[30] He is also of the opinion that schools in Germany are deliberately so bad that they produce as minor voters as possible and thus the needs of as many people as possible are disregarded, whereby they seek as many substitute satisfactions as possible, „[...] damit wir genügend Kunden für den Müll haben, den wir hier ihnen andrehen wollen [...]“ ("[...] so that we have enough customers for the rubbish that we want to sell them here [...]").[29]

German philosopher Richard David Precht considers it questionable to dictate to children how to spend a large part of their most formative and most important developmental phase and questions whether what is currently happening in schools and what the school is doing is a justification to „[...] Kindern 10.000 Stunden [an] Lebenszeit abzuzwacken“ ("[...] stifle children 10,000 hours [of] life").[31] He is of the opinion that in times of rapid information retrieval via the Internet, schools are faced with different pressure to justify themselves than they used to.[32] As the primary mediator of knowledge, the school has become dispensable, which is why, in his opinion, the school's learning objectives should shift the focus from imparting knowledge to promoting the development of personality, teamwork, creativity, etc.[32] He assumes that in the future more and more parents will ask themselves why they should send their children to school.[32]

Some educational researchers see the Schulpflicht as counterproductive and criticize it as a cause for rejection of certain educational content and poor performance. The sociologist Ulrich Oevermann, for example, is in favor of abolishing the Schulpflicht because it would systematically prevent what it promises. He criticizes the „Trichterpädagogik“ ("funnel pedagogy") and conceives a Socratic maeutic pedagogy of understanding.[17]

It is criticized that with the Schulpflicht, children would be unceremoniously assumed to be unwilling or unable to educate themself or to be educated outside a school and parents would be imputed nationwide inability to raise their children.[19][33]

On December 8, 2014, German radio station Deutschlandfunk Kultur did an interview with a German father who unschools his children and says that the Schulpflicht is to „[...] lernen, sich unterzuordnen [...]“ (" [...] learn to submit [...]").[14] He thinks that the Schulpflicht „[...] Lernen behindert und Mündigkeit erstick [...]“ ("[...] hinders learning and stifles maturity [...]") and that communication and discussion are strictly regulated in school.[14]

On November 8, 2018, police wanted to force a 15-year old school refusal to school in Halle-Neustadt and came to her home, whereupon she fled to the balcony and jumped down.[3] Resuscitation measures were carried out and the victim was taken to hospital.[3] At around 8:55 a.m., the police was informed by the rescue control center that the girl had died despite intensive rescue measures.[3]

Some believe that one factor of the fact that the Schulpflicht will be maintained is that school costs, for example with school trips and school tutoring, has become an important economic factor in Germany.[34][35]

It has been criticized that the Schulpflicht is also maintained during the COVID-19 pandemic in many German states, which increases the likelihood that students will be infected.[36][37] The hygiene measures in German schools are also criticized,[38] and politicians are accused of denying that there are many Corona cases in German schools.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44] There were also demonstrations organized by students themeselfes.[45] Baden-Württemberg ist the only state in Germany that has temporarily suspended the school attendance factor of the Schulpflicht for undefined time,[37] meaning that students can take advantage of distance education if their parents request it.[46][47] After estimates of the Deutscher Lehrerverband, 300,000 students (about 2.7% of all students) and 30,000 teachers in Germany are in quarantine as of November 2020.[48]

According to German business journalist Rainer Hank, the Schulpflicht and the associated educational monopoly harm learning.[7] He thinks that this monopoly is not well founded and that there are many factors which speak against the quality of state schools in Germany like the repeated Pisa findings and the increasing student exodus to private schools.[7]

German pedagogue Volker Ladenthin thinks that German parents have more confidence in the state than in most other countries which is why there are many people in Germany who do not question the Schulpflicht.[7]

The argument that parallel societies would be formed without compulsory schooling is criticized as experience from other countries shows that this is almost not the case and many see school itself as a kind of parallel society.[7][49] For example, it is criticized that many of the things taught in schools have little in common with everyday life and that many things that would be important for life are not taught in schools.[50]

German libertarian party Party of Reason (PDV) wants to replace the Schulpflicht with a compulsory education law in its party program, arguing that compulsory schooling specifies how education should be achieved, although school may not be ideally suited as a form of education for everyone.[51] The party also criticizes „[...] Das [...] staatliche Bildungsmonopol [...]“ ("[...] The [...] state educational monopoly [...]"), arguing that „[...] die Geschichte [hat] uns gelehrt, dass der Staat kein neutraler Spieler in der Bildung ist [...]“ ("[...] history [has] taught us that the state is not a neutral player in education. [...]").[51] They say that „Bildung ist von so großer Bedeutung, dass sie keinem politischen Einfluss unterliegen darf“ ("Education is so important that it cannot be subject to political influence") and claim that the Schulpflicht was introduced under Adolf Hitler so that children could be taught by state control.[51]

Literature

- Hermann Avenarius, Hans Heckel, Hans-Christoph Loebel: Schulrechtskunde. Ein Handbuch für die Praxis, Rechtsprechung und Wissenschaft. 7. Auflage. Luchterhand, Neuwied 2006, ISBN 3-472-02175-6.

- Bertrand Stern: Schluß mit Schule! – das Menschenrecht, sich frei zu bilden. Tologo Verlag, Leipzig 2006, ISBN 3-9810444-5-2.

- Bertrand Stern: Schule? Nein danke! Für ein Recht auf freie Bildung! In: Kristian Kunert (publisher): Schule im Kreuzfeuer. Auftrag – Aufgaben – Probleme. Ringvorlesung zu Grundfragen der Schulpädagogik an der Universität Tübingen. Schneider Verlag Hohengehren, Baltmannsweiler 1993, ISBN 3-87116-918-8.

- Bertrand Stern: Zum Ausbruch aus der Beschulungsideologie: Gute Gründe, auch juristisch den Schulverweigerern unser prospektives Vertrauen zu schenken. In: Matthias Kern (publisher): Selbstbestimmte und selbstorganisierte Bildung versus Schulpflicht. tologo, Leipzig 2016, ISBN 978-3-937797-59-5.

- Pachtler, Georg Michael, 1825–1889, Verfasser (1876), Die geistige Knechtung der Völker durch das Schulmonopol des modernen Staates (in German), Habbel, OCLC 1070781020, retrieved 2020-04-02CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schlaffke, Winfried. (1997), Freie Schulen – eine Herausforderung für das staatliche Schulmonopol (in German), Adamas-Verl, ISBN 3-925746-48-X, OCLC 75882418, retrieved 2020-04-02

External links

- Schulpflicht on the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education

References

- "Die Schulpflicht | Minilex". www.minilex.de. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Schulpflicht | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- "Wegen Schulschwänzerei: 15-Jähriges Mädchen stürzt in Halle-Neustadt in den Tod – Du bist Halle" (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- "Erzwingung des Schulbesuchs durch die bayerische Polizei: Freiheit oder Schulpflicht". eigentümlich frei (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- "Rechtsprobleme an der Schule und im Unterricht | Smartlaw-Rechtstipps". Smartlaw (in German). 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- "Schulpflicht geht vor Infektionsschutz". donaukurier.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- "Erklär mir die Welt (73) Warum ist die staatliche Schulpflicht unnötig?". FAZ.NET (in German). 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- "documentArchiv.de - Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs ["Weimarer Reichsverfassung"] (11.08.1919)". www.documentarchiv.de. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- "Anzeige von Das Recht auf Bildung und das besondere Recht auf Bildung | Zeitschrift für Inklusion". www.inklusion-online.net. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- BVerfG, 2 BvR 1693/04 vom 31. Mai 2006, Abs. 16 aa.

- Tenorth, Heinz-Elmar. "Kurze Geschichte der allgemeinen Schulpflicht | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Wrase, Michael. "Bildungsrecht – wie die Verfassung unser Schulwesen (mit-) gestaltet | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- Toyka-Seid, Gerd Schneider, Christiane. "Schulpflicht | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Ein Vater erzählt - "Mein Kind geht nicht zur Schule"". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- http://www.kandidatenwatch.de/erwin_huber-120-16282--f143173.html#frage143173

- "Homeschooling & Co. als Alternative?". www.trendyone.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Tenorth, Heinz-Elmar. "Kurze Geschichte der allgemeinen Schulpflicht | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- "#FridaysforFuture - Ein Argument gegen die Schulpflicht". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Müller, Verena (2020-02-03). "Verstoß gegen Schulpflicht: Welche Strafen Freilernern drohen". www.morgenpost.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- (PDF). 2007-06-10 https://web.archive.org/web/20070610180336/http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/4session/A.HRC.4.29.Add.3.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2020-11-02. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Heimunterricht muss erlaubt sein". m.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Dubro, Lukas (2010-01-27). "Flucht vor der Schulpflicht: Deutsche erhalten US-Asyl". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- "Homeschooling: Familie Romeike bekommt doch kein Asyl in den USA - DER SPIEGEL - Panorama". www.spiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- "USA: Kein Asyl für deutsche Schulverweigerer". kath.net katholische Nachrichten (in German). 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Stern, Bertrand (2006). Schluß mit Schule! das Menschenrecht, sich frei zu bilden. tologo Verlag. ISBN 978-3-940596-39-0. OCLC 879500374.

- Interaktiver Kongress (interactive congress" "EMPOWER THE CHILD" with Regina Sari: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=JoW7I_IL7p8

- "Die Stiftung | Stiftung Bertrand Stern" (in German). Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- "Gerald Hüther: Schule und Gesellschaft – die Radikalkritik". Stifterverband (in German). 2015-10-28. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=3Bn6RzBZlJ4

- In a conversation with the German journalist Reinhard Kahl on the subject of education, Richard David Precht gave his opinion on the school. An excerpt from the conversation can be seen here on YouTube.

- ZDF: Volle Kanne, airing from May 23, 2013 with Richard David Precht. A reupload can be seen here on YouTube.

- "Bildungssystem - Die Schulpflicht gehört abgeschafft!". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- "Wer bezahlt die Schule?". www.fr.de (in German). 2005-08-09. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ""Bewusstsein schafft Visionen" - Bertrand Stern zum Ausbruch aus der Schulpflicht - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Schulpflicht: Darf der Staat Kinder in den Unterricht zwingen, wenn er dort den Gesundheitsschutz nicht gewährleisten kann?". News4teachers (in German). 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Jetzt ist klar: Der Staat kann (und will) den Gesundheitsschutz in Schulen nicht gewährleisten – hebt die Schulpflicht auf!". News4teachers (in German). 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Zimmermann, Olaf; Wochenblatt, Redaktion Elbe. "Wie sicher sind Schulen? | Elbe Wochenblatt" (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Redaktion (2020-11-09). "Schulen sind sicher? Wie wäre es mal mit der Wahrheit, Kultusminister?". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Redaktion (2020-11-13). "Werden Kitas und Schulen jetzt doch zu Corona-Hotspots? Interne Daten von Bund und Ländern zeigen drastische Entwicklung auf". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Redaktion (2020-11-17). "Virologin Eckerle: Kinder spielen jetzt eine größere Rolle im Infektionsgeschehen". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- Redaktion (2020-11-19). "Wie Schulleitungen vom Land unter Druck gesetzt werden, Probleme mit Corona zu verschweigen – und zu lügen ("Ihre Schule ist sicher")". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Redaktion (2020-11-20). "Größter Ausbruch an Schule in Deutschland – ausgerechnet in Hamburg (wo der Bildungssenator gestern die Schulen für sicher erklärt hat)". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- Redaktion (2020-11-22). "Kultusminister weigern sich weiter, den RKI-Empfehlungen für Schulen zu folgen – Wissenschaftler: Schulen sind Treiber der Pandemie". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Redaktion (2020-12-05). "Gegen Präsenzunterricht um jeden Preis: Schüler machen mobil – und organisieren sogar eigenmächtig Wechselunterricht". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- "In Baden-Württemberg startet das neue Schuljahr – ohne Schulbesuchspflicht". News4teachers (in German). 2020-09-12. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Kultusministerium informiert Schulen zum neuen Schuljahr". Baden-Württemberg.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Redaktion (2020-11-11). "Lehrerverband: 300.000 Schüler und 30.000 Lehrer sitzen derzeit in Quarantäne fest". News4teachers (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Lehn, Birgitta (2014-12-10). "Hausunterricht: Zum Lernen braucht's die Schule nicht". FAZ.NET (in German). Retrieved 2020-12-25.

- Online, FOCUS. "Statt Geometrie und Gedichtanalyse: Was hätten Sie gerne in der Schule gelernt?". FOCUS Online (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- "Bildung". parteidervernunft.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-11-02.