Second Catilinarian conspiracy

The second Catilinarian conspiracy, also known simply as the Catiline conspiracy, was a plot, devised by the Roman senator Lucius Sergius Catilina (or Catiline), with the help of a group of fellow aristocrats and disaffected veterans of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, to overthrow the consulship of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida. Late in the year of 63 BC, Cicero exposed the conspiracy and forced Catilina to flee from Rome. The conspiracy was chronicled by Sallust in his work The Conspiracy of Catiline, and this work remains an authority on the matter.

Composition of the conspiracy

Catiline had been an unsuccessful candidate in the consular elections of the previous year (64 BC) and he did not take this lightly. The knowledge that this would be his last chance to obtain the consulship led him to undertake a no-holds-barred election campaign. He had lost the support of many among the nobility in his previous campaign, which meant he had to look elsewhere to get the backing he needed.[1] He consequently turned increasingly towards the people, and especially those plagued by debts and other difficulties. Many of the other leading conspirators had faced political problems similar to his in the Senate.[2] Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, the most influential conspirator after Catiline, had held the rank of consul in 71 BC, but he had been cast out of the senate by the censors during a political purge in the following year on the pretext of debauchery.[3] Publius Autronius Paetus was also complicit in their plot, since he was banned from holding office in the Roman government. Another leading conspirator, Lucius Cassius Longinus, who was praetor in 66 BC with Cicero, joined the conspiracy after he failed to obtain the consulship in 64 BC along with Catiline. By the time that the election came around, he was no longer even regarded as a viable candidate. Gaius Cornelius Cethegus, a relatively young man at the time of the conspiracy, was noted for his violent nature. His impatience for rapid political advancement may account for his involvement in the conspiracy.[4] The ranks of the conspirators included a variety of other patricians and plebeians who had been cast out of the political system for various reasons. Many of them sought the restoration of their status as senators and their lost political power.

Promoting his policy of debt relief, Catiline initially also rallied many of the poor to his banner along with a large portion of Sulla’s veterans.[5] Debt had never been greater than in 63 BC since the previous decades of war had led to an era of economic downturn across the Italian countryside.[6] Numerous plebeian farmers lost their farms and were forced to move to the city, where they swelled the numbers of the urban poor.[7] Sulla's veterans were in bad economic straits as well. Desiring to regain their fortunes, they were prepared to march to war under the banner of the "next" Sulla. Thus, many of the plebs eagerly flocked to Catiline and supported him in the hope of the absolution of their debts.

Course of the conspiracy

Catiline sent Gaius Manlius, a centurion from Sulla’s old army, to manage the conspiracy in Etruria where he assembled an army. Others were sent to aid the conspiracy in important locations throughout Italy, and even a small slave revolt which had begun in Capua. While civil unrest was felt throughout the countryside, Catiline made the final preparations for the conspiracy in Rome.[8] Their plans included arson and the murder of a large portion of the senators, after which they would join up with Manlius’ army. Finally, they would return to Rome and take control of the government. To set the plan in motion, Gaius Cornelius and Lucius Vargunteius were to assassinate Cicero early in the morning on November 7, 63 BC, but Quintus Curius, a senator who would eventually become one of Cicero's chief informants, warned Cicero of the threat through his mistress Fulvia. Cicero escaped death that morning by placing guards at the entrance of his house, who managed to scare the conspirators away.[9]

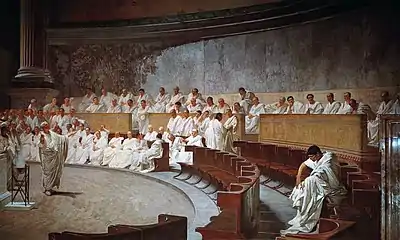

On the following day, Cicero convened the Senate in the Temple of Jupiter Stator and surrounded it with armed guards.[10] Much to his surprise, Catiline was in attendance while Cicero denounced him before the Senate and it's been said that the senators adjacent to Catiline slowly moved away from him during the course of the speech, the first of Cicero's four Catiline Orations. However, some sources suggest that the Senate didn't believe Cicero at all.[11] Incensed at these accusations, Catiline exhorted the Senate to recall the history of his family and how it had served the republic, instructing them not to believe false rumors and to trust the name of his family. He finally accused them of placing their faith in a "novus homo", Cicero, over a "nobilis", himself. Supposedly, Catiline violently concluded that he would put out his own fire with the general destruction of all.[12] Immediately afterward, he rushed home and the same night ostensibly complied with Cicero's demand and fled Rome under the pretext that he was going into voluntary exile at Massilia because of his "mistreatment" by the consul; however, he arrived at Manlius’ camp in Etruria to further his designs of revolution.[13]

While Catiline was preparing the army, the conspirators continued with their plans. The conspirators observed that a delegation from the Allobroges was in Rome seeking relief from the oppression of their governor. So, Lentulus Sura instructed Publius Umbrenus, a businessman with dealings in Gaul, to offer to free them of their miseries and to throw off the heavy yoke of their governor. He brought Publius Gabinius Capito, a leading conspirator of the equestrian rank, to meet them, and the conspiracy was revealed to the Allobroges.[14][15] The envoys quickly took advantage of this opportunity and informed Cicero, who then instructed the envoys to obtain tangible proof of the conspiracy. Five of the leading conspirators wrote letters to the Allobroges so that the envoys could show their people that there was truly a conspiracy which had the potential to succeed. However, a trap had been laid. These letters were intercepted in transit to Gaul at the Milvian Bridge.[16] Then, Cicero had the incriminating letters read before the Senate the following day, and shortly thereafter these five conspirators were condemned to death without a trial despite an eloquent protest by Julius Caesar.[17] Fearing that other conspirators might try to free Sura and the rest, Cicero had them strangled in the Tullianum immediately. He even escorted Sura to the Tullianum personally.[18] After the executions, he announced to a crowd gathering in the Forum what had occurred. Thus, an end was made to the conspiracy in Rome.

Aftermath

The failure of the conspiracy in Rome was a massive blow to Catiline's cause. Upon hearing of the death of Lentulus and the others, many men deserted his army, reducing the size from about 10,000 to 3,000. He and his ill-equipped army began to march towards Gaul and then back towards Rome again, they repeated this several times in a vain attempt to avoid a battle. However, Catiline was forced to fight when Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, propraetor of Cisalpine Gaul, blocked him from the north with three legions. So, he chose to engage Antonius Hybrida's army near Pistoia, hoping that he could defeat Antonius in the ensuing battle and dishearten the other Republican armies. Catiline also hoped that he might have an easier battle against Antonius who, he assumed, would fight less determinedly, as he had once been allied with Catiline.[19] In fact, Catiline may have still believed that Antonius Hybrida was conspiring with him—which may have been true, as Antonius Hybrida claimed to be ill on the day of the battle and left the fighting to his subordinate Marcus Petreius.[20]

Catiline and all his troops fought bravely, with Catiline himself fighting on the front lines. Once Catiline saw that there was no hope of victory, he threw himself into the thick of the fray. When the corpses were counted, all Catiline's soldiers were found with frontal wounds, and his corpse was found far in front of his own lines. In Catiline's War, the 1st-century BC Roman historian Sallust gives the following account:

When the battle was ended it became evident what boldness and resolution had pervaded Catiline's army. For almost every man covered with his body, when life was gone, the position which he had taken when alive at the beginning of the conflict. A few, indeed, in the centre, whom the praetorian cohort had scattered, lay a little apart from the rest, but the wounds even of these were in front. But Catiline was found far in advance of his men amid a heap of slain foemen, still breathing slightly, and showing in his face the indomitable spirit which had animated him when alive.[21]

See also

- First Catilinarian conspiracy

- Sempronia, a woman who was involved in the conspiracy

Footnotes

- Kathryn Tempest, Politics and Persuasion in Ancient Rome

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XVII

- Dio Cassius XXXVII.30.4; Plutarch, Cicero 17.1

- Cicero, In Catilinam III.16 IV.11

- Cicero, In Catilinam II.8 IV.6; Cicero, Pro Murena LXXVIII-LXXIX; Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXXVII.1

- Cicero, De Officiis II.84

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXXVII

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXVII.1-2 XXX.1-2; Cicero, Pro Murena XLIX

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXVII.3-XXVIII.3

- Cicero, In Catilinam I.21

- http://www.ancient.eu/article/861/

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXXI.5-9

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XXXII.1 XXXIV.2; Cicero, In Catilinam II.13

- Cicero, In Catilinam III.4; Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XL

- Gill, N. S. "Conspiracy of Catiline". About.com. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Cicero, In Catilinam III.6; Sallust, Bellum Catilinae XLV

- "Chronology of Catiline's Conspiracy". The Latin Library. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae LV.5-6

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae LVI-LXI

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae LIX

- Sallust, Catiline's War, Book LXI, pt. 4 (translated by J. C. Rolfe).