Seed ball

Seed balls, also known as "earth balls" or nendo dango (Japanese: 粘土団子), consist of a variety of different seeds rolled within a ball of clay, preferably volcanic pyroclastic red clay. Various additives may be included, such as humus or compost. These are placed around the seeds, at the center of the ball, to provide microbial inoculants. Cotton-fibres or liquefied paper are sometimes mixed into the clay in order to strengthen it, or liquefied paper mash coated on the outside to further protect the clay ball during sowing by throwing, or in particularly harsh habitats.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Development of technique

.jpg.webp)

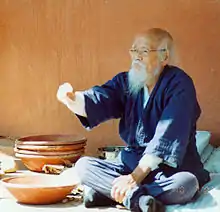

The technique for creating seed balls was rediscovered by Japanese natural farming pioneer Masanobu Fukuoka.[1] The technique was also used, for instance, in ancient Egypt to repair farms after the annual spring flooding of the Nile. In modern times, during the period of the Second World War, this Japanese government plant scientist working in a government lab, Fukuoka, who lived on the mountainous island of Shikoku, wanted to find a technique that would increase food production without taking away from the land already allocated for traditional rice production which thrived in the volcanic rich soils of Japan.[2][3]

Construction

To make a seed ball, generally about five measures of red clay by volume are combined with one measure of seeds. The balls are formed between 10mm and 80mm (about ½" to 3") in diameter. After the seed balls have been formed, they must dry for 24-48 hours before use.

Seed bombing

History of seed bombing

Seed bombing is the practice of introducing vegetation to land by throwing or dropping seed balls. It was made popular by green movements such as guerrilla gardening as a way to practice active reforestation.

Seed balls were also experimentally used in aerial seeding in Kenya in 2016.[4][5] This was an attempt to improve the yield of standard aerial seeding.

Aerial seeding (or aerial reforestation) is the technique of spreading seeds from an airplane, helicopter or a similar flying transport. It can be considered a particular type of direct seeding: as such, it introduces seeds directly in the field and it is often not economical due to the issues of germination, pests and seed predation by rodents or other wild animals. Transplanting seedlings from a plant nursery to the field is a more effective sowing technique.

Aerial seeding has a low yield and require 25% to 50% more seeds than drilled seeding to achieve the same results.[6] It is sometimes used as a technique to plant cover crops without having to wait for the main crop's off-season.[6] The earliest attempts at aerial reforestation date back to the 1930s. In this period, planes were used to distribute seeds over certain inaccessible mountains in Honolulu after forest fires.[7] These experiments were largely unsuccessful, because of poor seed dispersal: seeds failed to obtain enough kinetic energy to enter the soil and as a result were massively predated. This in turn generated an infestation of rodents in Hawaii.[8][9]

The use of seed balls, instead of simple seeds, to perform aerial reforestation in Kenya seems to have produced desirable results.[10] Chardust Ltd, the company involved and distributing seed balls for that project, claims to have sold and distributed over 7 million seedballs, as per August 2019.[11] It is likely, though, that the majority of these seed balls are deployed traditionally instead than via aerial seeding and there is no published data to support the benefits of using seed balls via aerial seeding.

In 1987, Lynn Garrison proposed the creation of a Haitian Aerial Reforestation Project (HARP), by which tons of seed would be scattered from specially modified aircraft. The seeds would be encapsulated in an absorbent material. This coating would contain fertilizer, insecticide/animal repellent and, perhaps a few vegetable seeds. Haiti has a bimodal rainy season, with precipitation in spring and fall. The seeds could have been moistened a few days before the drop, to start germination. Unfortunately the project never came to fruition.

Another more recent project idea was to use saplings instead of seeds in aerial.[7] Saplings would be encased in sturdy and biodegradable containers which would work as projectiles and pierce the ground at high velocity. This would likely guarantee a better yield when compared to simple aerial seeding or even seed bombing.

This project was being developed in 1999 by a company called Aerial Reforestation Inc, in Newton, Massachusetts, based on an original idea by pilot Jack Walters.[12] The company was planning to use military transport aircraft C-130, traditionally used to lay out landmines on combat fields.[7] As per 2019 the company does not seem to be operating anymore. [13] Other researchers are still investigating the potential of these "aerial sapling darts", by improving their aerodynamics to achieve better soil penetration and therefore higher reforestation yields.[8] More research is needed to assess exactly their performance against other reforestation methods.

The most recent attempt at Seed Bombing is performed by DroneSeed, a company that has become operative in 2019. They claim to have devised a proprietary seed bomb that is able to deter animals from eating the seeds and, by using a mix of different seeds in the same bomb, to maximize the yield of the tree planting operations. [14] Given the focus of this company on disaster relief, they have considered sapling darts not to be an effective solution since "nursery suppliers lack capacity to reforest after sizeable wildfires — especially repeat fires." [14]

Feasibility and weaknesses

Despite its low yield, interest in aerial seeding has recently grown, while searching for a quick system to obtain reforestation and fight global warming. The advantage of using an airplane/helicopter is the ability to quickly seed large areas, even remote areas, otherwise impractical to be used in active reforestation.

Aerial seeding is therefore best suited to sites whose remoteness, ruggedness, inaccessibility, or sparse population make seedling planting difficult. It is particularly appropriate for "protection forests" because helicopters or planes can easily spread seed over steep slopes or remote watersheds and isolated dryland areas. It seems also well suited for use in areas where there may be a dearth of skilled laborers, supervisors, and funds for reforestation. It has the potential to help increase production of tree crops for forage, food, and honey as well as wood for fuel, posts, lumber, charcoal and pulp.

Seed balls and aerial reforestation are heavily sensitive to environmental conditions. Seeds deployment may not be practical in some cases because the site may require preparation or the season may be wrong. To germinate successfully, seeds usually must fall directly onto mineral soil rather than onto established vegetation or undecomposed organic matter. Where organic matter has accumulated thickly, the site must normally be burned, furrowed, or disked. The soil disturbance left after logging is often sufficient. Rough terrain is more amenable to broadcast seeding, but yields are typically low even in the best conditions.

On certain sites ground preparation may be necessary. Site preparation and the seeding operation must be well coordinated to meet the biological requirements for prompt seed germination and seeding survival. Dry sites may have to be specially ridged or disked so as to optimize the rainfall that reaches the seed. Excessively wet sites may need to be ridged or drained.

The degree of field slope is not critical as long as seeds find a receptive seedbed. Steep watersheds, eroding mountain slopes, bare hillsides, and spoil-banks where vegetation is sparse are often suitable for aerial seeding (however, on some steep slopes with smooth, bare soil, rain may wash the seeds away too easily for successful seeding).

Arid and savanna lands (for example, those where annual rainfall is under 800 mm) are most in need of reforestation. These are regions where aerial seeding in principle has exceptional potential. They include vast tracts of unused or poorly used land that has sparse tree cover and that is not confined to private land holdings, so it is generally accessible to aircraft. The native trees (such as species of Acacia, and other genera) in these areas are generally well adapted for survival under difficult field conditions. These are not species for timber as much as for firewood, forage, fruit, gum, erosion control, and other such uses.

.jpg.webp)

As a prerequisite to any method of reforestation, the species selected must be adapted to the temperature, length of growing season, rainfall, humidity, photoperiod, and other environmental features of the area. Ideally, before aerial seeding takes place trial plots should be established to test those species most likely to germinate and grow successfully on the chosen sites. Even when one species has the right characteristics, it may be prudent to test seed of different provenances to find those best suited to the site.

Characteristics that make a particular species more or less appropriate for aerial seeding include:

- seed size

- seed availability

- ability of the seed to germinate on the soil surface

- germination and seedling growth speeds

- ability to withstand temperature extremes and prolonged dry periods (orthodox seed)

- ability to tolerate soil conditions

- light tolerance

- seed stability when stored in large quantities

- suitability of seed for handling with mechanical seeding devices,

- development speed of a deep taproot by seedlings to enable them to withstand adverse climatic conditions in the period following germination.

Species with highly palatable seeds have little prospect of success because wildlife eat the seed before it has a chance to germinate unless it is pelletized. Also, small seeds and lightweight, chaffy seeds are more likely to drift in the wind, so they are harder to target during the drop. Small seeds, however, fall into crevices and are then more likely to get covered with soil, thereby enhancing their chances of survival. Aerial seeding may prove to work best with "pioneer" species, which germinate rapidly on open sites, are adapted for growth on bare or disturbed areas, and grow well in direct sunlight.

Crop Spraying Aircraft

It is the most common method and the one practiced by Farmland Aviation, Kenya, one of the few companies active in this field. They claim to be able to spread up to six tons of tree seeds per hour over tens of thousands of acres.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

Until recently (2017), drones were not used in aerial seeding. Low-cost UAV's lacked payload capacity and range limits them for most aerial seeding applications. A drone developed by Parrot SA and BioCarbon Engineering however has solved this issue. It is capable of dropping 100 000 pods a day.[15][16]

Paragliding

This deployment method is being tested in Kenya and holds promises of great reforestation rates because of low cost, low speed and altitudes, even if seed spraying rate is likely to be much slower than deployment by aircraft.

Guerrilla gardening

The term "seed green-aide" was first used by Liz Christy in 1973 when she started the "Green Guerrillas".[17] The first seed green-aides were made from condoms filled with tomato seeds, and fertilizer.[18] They were tossed over fences onto empty lots in New York City in order to make the neighborhoods look better. It was the start of the guerrilla gardening movement.[19]

See also

- The One-Straw Revolution

- Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney, a 1982 children's book emphasizing public seed scattering

- Seed dispersal

- Johnny Appleseed

- Operation Overgrow

- Diggers

References

- Adler, Margot (April 15, 2009). "Environmentalists Adopt New Weapon: Seed Balls". NPR. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- Fukuoka (福岡), Masanobu (正信) (May 1978) [1st publ. in Japanese September 1975], Larry Korn (ed.), The One-Straw Revolution An Introduction to Natural Farming, translated by Chris Pearce; Tsune Kurosawa; Larry Korn, Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale Press, ISBN 0878572201

- Fukuoka (福岡), Masanobu (正信) (December 1987) [1st publ. in Japanese December 1975], The Natural Way of Farming The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy, translated by Frederic P Metreaud (rev. ed.), Tokyo: Japan Publications, ISBN 978-0-87040-613-3

- Cookswell Jikos (2016-08-07), Dryland aerial forest restoration using biochar seedballs - Kenya Aug 2106, retrieved 2018-03-25

- Aerial tree seeding for landscape forest restoration in East Africa, retrieved 2019-08-28

- U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Aerial seeding of cover crop (PDF), retrieved 2019-08-28

- Horton, Jennifer. "Could military strategy win the war on global warming?". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Stewart, Jack, Lecture on Reforestation by Aerial Darts, University of Glasgow 2016, retrieved 2019-08-28

- Chimera, Charles (2009-11-18), Could poor seed dispersal contribute to predationby introduced rodents in a Hawaiian dry forest? (PDF), retrieved 2019-08-28

- Daily Nation (2017-12-09), Meet the squad bombing forests to grow more trees, retrieved 2019-08-28

- Kinyanjui, Teddy, Throw and Grow Seedballs Kenya, retrieved 2019-08-28

- Brown, Paul (1999-09-02). "Aerial bombardment to reforest the earth". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- "The Ups and Downs of Aerial Reforestation". 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- "DroneSeed Official Website". 2019-10-27. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- Spray Tree Seeds From the Sky to Fight Deforestation

- New Drone Plans an Ambitious Mission to Plant 100,000 Trees a Day

- "Our History | Green Guerillas". www.greenguerillas.org. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- "How Guerrilla Gardening Works". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- Robinson, Joe (29 May 2008). "Guerrilla gardener movement takes root in L.A. area". L.A. Times. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

Further reading

- Smith, K. (2007). The guerilla art kit. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Huxta, B. (2009). Garden-variety graffiti. Organic gardening, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seed balls. |

- "What's a clay ball?" and "Clay Ball Method" advice derived directly from Fukuoka Masanobu by The RainMaker Project, a major project in Africa by Yokohama Art Project, Japanese NGO.

- Masanobu Fukuoka's patent for advanced seedballs, titled "Paper/seed-unified planting seed unit and preparation process thereof"

- Making Seed Balls, by Jim Bones, he learned personally from Fukuoka Masanobu and from his books.

- The Seed Ball Story, a video by Jim Bones about desert habitat restoration using seed balls in Big Bend National Park, Texas.

- The entire "Lost Seed Ball Pages" by Jim Bones, An early overview of seed ball production and uses, including instructions for making a von Bachmayr Rotary Drum.

- "Seed Balls R Us" A crossroads website dedicated to sharing seed ball information links and videos.

- "Seed Balls by Masanobu Fukuoka 1997" YouTube 18:43 long video, caption: "Natural Farmer Masanobu Fukuoka conducts a workshop for making seed balls at his natural farm and forest in Japan."

- Making Hay with Clay - Greece

- How to make seedballs

- A discussion of the pros and cons of different seed ball recipes

- 'On Seedballs', a website dedicated to seedballs

- Seed Bomb R&D forum come read and discuss about seed balls.

- Stuffyoushouldknow.com

- Wikihow.com

- Latimes.com

- Gardenista.com

- Articles.washingtonpost.com

- Permanentculturenow.com

- News.bbc.co.uk

- Npr.org

- News.bbc.co.uk

- Theguardian.com

- UK Seed Bomb Supplier, Seed Freedom

- The guerrilla gardener's seedbomb recipe

- Planning an Effective Seed Bomb Strike