Seine River Steamers

The Seine River was the scene of many early experiments with steam navigation. The steamship has a long ancestry, dating back at least to 1783 when the Marquis de Jouffray d'Abbans steamed his little boat, the Pyroscaphe, across the Seine. Robert Fulton even exhibited one to Napoleon's regime. With the success of the steam engine by the 1820s, the Second Republic embarked on a series of navigation improvements to raise weirs and locks with which to deepen the navigation channel. By the 1860s improvements had changed the riverbed from low-lying sand banks and trickle to a series of cascading ponds with a depth of 6 and a half feet.

Early history

Early experiments with steam were started in 1780s on the Rhone River in France, and were perfected with Fulton's boat on the Seine in 1803. The British had the early lead with steam, from James Watt, William Symington, and Henry Bell, and thus it became logical that the technology transfer would migrate across the English Channel. The Rob Roy did such a task in 1816, while the Aaron Maltby left London and sailed up the Seine to Paris in 1822. A charter was issued for a tourist day tripper steamboat company in Paris.

Alfred Binyon, an English cloth merchant, travelled to France to see a trade show and wrote of it:

"We took a hasty cup of coffee and went on board the Seine steam packet, a French built boat with English engines and engineer. The sail was delightful - the banks of the Seine are steep chalk cliffs on one side, and fine rich meadow land with abundance of cattle on the other. Baum said it was superior to the Rhine in many parts. We arrived at Rouen."

Many early vessels used Boulton and Watt steam engines.

Steamer Élise

The Élise was the first steamship to cross the English Channel.

She was bought in England 1814 by Pierre Andriel as Margery, and renamed Élise. Andriel intended to accomplish a spectacular crossing of the Channel to convince public opinion that steamships could be ocean-worthy. She sailed up the Seine and arrived in Paris on 28 March, becoming a popular sensation. Two small saluting guns were mounted at the bow and fired in honour of Louis XVIII

Chain tugs

Early tugs used chains in the river to tow trains of barges up river. The low steam pressure and low power of early vessels meant that positive traction by pulling on a chain against a deadman or anchor was much more effective. In the 1830s river travel was considered dangerous, so much so that insurers would put a 25 percent premium on cargoes and vessels travelling the route.

The Seine is divided into three sections, the lower or Oise section, middle or Paris Section, and upper or Marne section. Ships enter the river at Le Havre through a bad tidal bore. (Victor Hugo's favourite daughter was killed while travelling in a small boat across the bore.) Oceangoing ships can travel to Rouen, where small steamers take on loads for journey further up river.

Continuous improvements to the shipping lane meant that regular traffic could be maintained and not just in periods of high water.

Cortege of a cut-off Corsican

In 1840 when the French nation desired the return of Napoleon's body from the Island of St. Helena, to his adopted nation of France, he travelled by sailing frigate to Cherbourg, then to a series of steamers up the river. On 30 November, la Belle-Poule entered the roadstead of Cherbourg, and six days later the remains were transferred to the steamboat la Normandie. Reaching Le Havre, the coffin was then transferred to la Dorade 3 at Val-de-la-Haye, near Rouen, to be carried up the Seine, on whose banks people had gathered to pay homage to Napoleon. On 14 December la Dorade moored at the Courbevoie quay. He was then ceremonially re-interred at Les Invalides.

Cement to the City of Light

With Baron Haussmann's levelling of the centre of Paris and building the sewers and Boulevards, the river bank was also reconstructed the famous Quais on the Seine banks were erected.

The river provided the key to moving in building materials: timber, sand, bricks, stone, gravel and ironware were moved; wine, fruit, and hay; while manure, litter and rubble were removed from town. The Quais at Bersy, Rapee, Hotel de Ville and Louvre carried on trade. And by 1880, the trade was duty-free from tariffs.

The Canal de l'Ourcq was constructed in 1808 between the River Ourcq and the Seine. Its purpose was to provide Paris with drinking water and a new navigable waterway. Geometricians at heart, the engineers of the Empire dug the canal along the axis of the Rotunda. With the industrial revolution along came mechanical workshops and boiler-works, replacing the countryside. Warehouses sprang up along the banks as 10,000 barges delivered to the city each year their cargo of cereals, coal, and building materials. Factories were constructed and products as diverse as sugar and boots were produced.

During the Paris Commune bloodshed was so bad that the Seine ran red with blood.

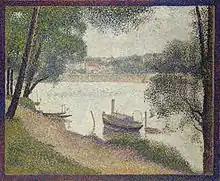

Lighters and light imagined by the impressionists

_-_'Morning%252C_Winter_Sunshine%252C_Frost%252C_the_Pont-Neuf%252C_the_Seine%252C_the_Louvre%252C_Soleil_D'hiver_Gella_Blanc'%252C_ca._1901.jpg.webp)

Traffic on the Seine entered into consciousness in a different way too—the Pre-Impressionist and impressionist painters would paint the River scenes from the Pont Neuf, to Argenteuil. And so we are left with colourful and sometimes cubist, copies of age old scenes.

Birth of the Bateau Mouche

In 1867, the year of an exposition, another famed Paris institution came into being—that of the Bateau Mouche. Sights-seeing steamers were built and steamed up and down the river, and under the low bridges. And they became a hit.

The individual pieces of the Statue of Liberty were barged down the Seine from the workshop, to a waiting ocean steamer for transhipment to New York about 1881. Louis Vuitton established his factory on the Seine at Asni so wood for his steamer trunks could be moved on the river

Floating swimming pools featured on the Seine, as did a series of laundries. The pools, dating from 1801and were used in the 1924 Olympics.

River steamers were used as hospital ships during the First World War, as the ghastily wounded British soldiers could be smoothly moved downriver to larger hospital ships at Le Havre.

Atlantic Salmon have naturally returned to the Seine almost a century after over fishing and pollution caused them to disappear.

See also

- L'Atalante classic barge, Seine film.