Shotley Grove

Shotley Grove is a small settlement on the river Derwent, about 1 mile upstream of Shotley Bridge in the County of Durham, England.

| Shotley Grove | |

|---|---|

Shotley Grove Location within County Durham | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Durham |

| Fire | County Durham and Darlington |

| Ambulance | North East |

Today Shotley Grove is a pleasant rural idyll on the outskirts of Shotley Bridge, but in the past it was a vibrant part of early industrial of England. The Derwent valley played an important part in the industrialisation of the North, where the fast flowing river provided motive power to the emerging coal, lead and iron industries.

German settlers

It is believed Shotley Bridge was established in the early 17th century by a group of German sword makers. Robert Surtees.[1] writing in 1820 states,

At Shotley-Bridge a colony of German Sword-cutlers, who fled from their own country for the sake of religious liberty, established themselves about the reign of King William. These quiet settlers, who brought with them habits of industry, and moral and religious principle, easily mingled with the children of the dale, and forgot the language of their forefathers. Few of the original names are now left, but the trade is still carried on, and sword-blades and scimitars of excellent temper are manufactured for the London market.

Tradition has it that the German colonists originated in Solingen, a small city on the river Wiffer, near Düsseldorf. Solingen was celebrated for its fine elastic Damascene sword blades. The colonists brought with them the art of manufacturing these fine swords – a skill which was not known in England at that time.

The German sword makers, on arriving in England, desired a secluded location where they could maintain the secrecy of their art. They searched many areas of England, and eventually fixed on a spot on Derwentside, upstream of the old Roman town of Ebchester. Here they found the Derwent water was particularly suited to the tempering of steel. Indeed, they believed the water to be second to only to that of the Tagus at Toledo, where the famous Toledon swordmakers crafted their Damascus blades.[2]

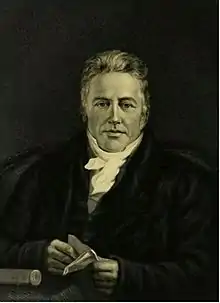

John Annandale

Shotley Grove first appears in the records in 1761, when a property deed describes a property belonging to Cuthbert Smith, of Snaws-Green . "... a parcel of land called Ealands, with a sword mill and a barley mill upon the same, lying near the mills there called Bishop's Mills, with a malting and a corn mill."[3]

In 1812, the property was sold to John Annandale,[4] and on possession, he renamed it 'Shotley Grove'.

John Annandale and his brother Alexander came originally from Scotland, and founded the firm of Messrs. John Annandale & Sons, Paper Manufacturers, on 1 May 1799 at Haughton Mill in Northumberland.

Shotley Grove Paper Mills

When John Annandale purchased the Shotley Grove Mills in 1812, the paper mill housed two vats, a beater, a washer, and a small drying house.[5] It probably produced no more than four tons of paper a week at first, but by the end of 1812 output of hand-made paper had increased to five or six tons a week.[6]

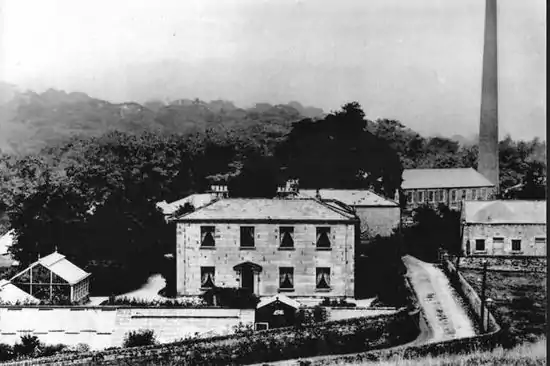

In 1826 John Annandale built a large house for his residence on the mill site. The house, known as Shotley Grove House, is shown in the photograph opposite, taken around 1900. It is one of the few buildings still remaining from the extensive 19th century works which can be seen in the background.

In 1828 the Low Mill was added just downstream of the High Mill. A map of 1829 shows both sites well developed with the mansion house and garden between them.

In 1841, Ryan[7] describes the scene…

Shotley Grove is the appropriate and euphonious name which the late John Annandale, Esq. gave the High Mill when he purchased the property about thirty years ago, and commenced those improvements which his talented Sons have so laudably continued, and which have added so much to the richness and beauty of the whole landscape. The lands adjoining their substantial and elegant residence, and the flourishing plantation grounds, used to be proverbially poor farms and sterile fields, scarcely worth any cultivation, but are now extremely luxuriant and productive, and in the highest stage of agriculture – so much can judicious management accomplish in a few years….The whole of the estate, which is now very extensive, the magnificent manufactories of the first order, the clear water ponds around the house and in the rich gardens, the woods, plantations, and groves on all sides, and the verdant meadows and lawns present a rare combination of the town's opulence and the country's simplicity and retirement, of commerce and agriculture embracing each other, and both retaining their respective advantages and rural attractions.

In the early days of Annandale's mills, the paper was made largely by hand, sheet by sheet. The pulp was pressed between squares of felt, then dipped into sizing, and hung up to dry in the drying house. Conditions during this early period were described by one of the managers:

As a lad I had to empty chests by myself with a grape or hand hook, my fingers would often bleed and my lungs often felt as though they were bursting with the fumes [bleach and vitriol] and the effort. Rag boilers were just open pans, all of the rags and rope were man-handled ... When a beater was emptied into the chest, a large hand bell was vigorously rung to warn the machine men to put more water on.[8]

John Annandale, who had set up the business in 1799, was by reputation, a man of great energy and perseverance, who understood all the departments of the business. He was admitted by his most experienced workmen to be a thorough paper maker, an upright man and good Master, though a strict disciplinarian.[9] In 1834 he died, leaving the management of the mill to his widow, six sons and two daughters[10]

An inspection for the Royal Commission into the Employment of Children in 1843 noted fifteen children, employed at Shotley Grove Mill. Young girls were found to be working in the rag house cutting rags from 6.30 am until 6 pm, six days a week, and were paid 6d a day at nine years of age. They ate their meals in the rag room, with the dust in the air so thick as to cover their food. Coughs and extreme shortness of breath, also torn or cut hands, were commonplace. Despite this, the mill was noted to have the best-ventilated rag cutting room in the district[11]

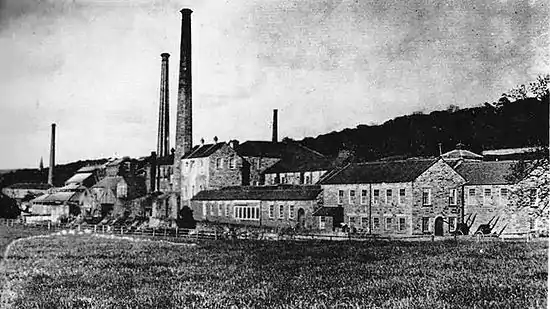

However, in the course of a few years, the industry was revolutionised by Fourdrinier's continuous paper-making machines. Such a machine was installed at Shotley Gove, and in 1857 Fordyce[12] reported that the water wheels had largely been replaced by more powerful and reliable steam engines.

A further great impetus to the trade was provided in 1860, when William Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer, abolished the duty on paper, or as it was called, the "Tax upon Knowledge". (The Bill was initially rejected by the House of Lords, as they believed cheap publishing would encourage the dissemination of radical working class ideas).

The prosperity of the Shotley Grove mills at this time is described in a series of articles in the Newcastle Guardian.[13] Like Ridely in 1841, the reporter emphasises the natural beauty of the location: "It is a place in which you might make love as well as paper." The articles also provide a detailed description of the paper making process at Shotley Grove, as well as the working conditions.

Up until this time, the main raw material for paper had been cotton rags, most of which were gathered locally and brought to the mill by Rag and Bone dealers and 'Candy Men'. However, even from the earliest days of the mill, the records show the Annandales importing rags from France and Germany[14]

As the volume of the paper trade grew, the supply of rags became more scarce, and in the 1870s the Annandales began to use Esparto grass from Spain as a raw material. Over fifty tons per week were consumed at Shotley Grove.

The capacity of the mills continued to expand through the next decades. In 1881, about 300 workers were employed, producing about 40–50 tons of finished paper per week.[15]

In 1894 the mill reached its peak production of about 95 tons of paper a week, and was described in this period as one of largest manufacturers in the United Kingdom.[16]

Decline and closure

In the last decade of the 19th century, the paper mills at Shotley Grove found it increasingly difficult to business began to compete with the much larger scale wood-pulp processes emerging elsewhere across Europe. The mills drifted into decline and by 1907 Shotley Grove was advertised for sale. No buyer could be found for the mills as a going concern, so the works was shut down between 1908 and 1911. The mill buildings were demolished and the machinery was auctioned off – some of it reputedly being shipped to India.

Today, there is very little evidence of the great industry that was Annandale's Shotley Grove Paper Mills. The only remaining buildings are the workers cottages, the mansion house and stables. The mansion house, now known simply as Grove House is referenced in Pevsner's Buildings of England.[17]

Range of paper products

During much of its 100-year history, the reputation of Shotley Grove Paper mills was built on the quality of its cartridge paper, as supplied to Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

However, through the years, they also produced a wide variety of other papers, including the blue paper used by chemists to wrap Seidlitz powders and the paper from which collars, cuffs, and even shirt-fronts were made. Stirk[18] lists the range of papers produced at Shotley Grove...

- Writing paper

- Cartridge paper

- Self blue paper (a paper that is derived from indigo-dyed rags)

- Envelope papers

- Fine printing paper

- Blotting paper

- News paper

- Collar paper (for manufacture of paper shirt collars)

- Cartridge paper for hosiery packaging

- Long elephants (for printing as wall paper)

- Manilla cartridges

- Envelope paper

- Gummed papers

- Surfacing paper

- Chromo (a type of coated paper used during the 19th- century to print chromolithographs)

- Enamelling and Super-calendered papers (High gloss papers for colour printing)

References

- Surtees, Robert (1820). The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham: volume 2: Chester ward. pp. 284–297.

- Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend. II (15). May 1888. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "The Consett Story". Derwentside.com. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Neasham, G (1881). The History & Biography of West Durham. p. 80.

- The Paper Maker's Circular. XXIX (340): 256. 10 June 1899. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Neasham, G (1881). The History & Biography of West Durham. p. 80.

- Ryan, Reverend John (1841). History and Vicinity of Shotley Bridge. Sunderland. p. 66.

- Moore, T (1988). The industrial Past of Shotley Bridge & Consett. p. 4.

- Neasham, G (1881). The History & Biography of West Durham. p. 80.

- Last Will and Testament of John Annandale. National Archive: Public Records Office of England and Wales. 1834.

- Moore, T (1988). The industrial Past of Shotley Bridge & Consett. p. 4.

- Fordyce, W (1855). History & Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, Volume 2.

- "Newcastle Guardian". Newspaper. 10 November 1860.

- "Shipping news". Durham County Advertiser. 3 December 1814.

- Stirk, Jean (July 2000). "BRITISH PAPER MILLS: SHOTLEY GROVE MILLS". The Journal of the British Association of Paper Historians (35).

- Stirk, Jean (July 2000). "BRITISH PAPER MILLS: SHOTLEY GROVE MILLS". The Journal of the British Association of Paper Historians (35).

- Pevsner, Nikolas (1983). County Durham (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England) (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300095996.

- Stirk, Jean (July 2000). "BRITISH PAPER MILLS: SHOTLEY GROVE MILLS". The Journal of the British Association of Paper Historians (35).