Siege of Berwick (1333)

The siege of Berwick lasted four months in 1333 and resulted in the Scottish-held town of Berwick-upon-Tweed being captured by an English army commanded by King Edward III (r. 1327–1377). The year before, Edward Balliol had seized the Scottish Crown, surreptitiously supported by Edward III. He was shortly expelled from the kingdom by a popular uprising. Edward III used this as a casus belli and invaded Scotland. The immediate target was the strategically important border town of Berwick.

| Siege of Berwick | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second War of Scottish Independence | |||||||||

A medieval depiction of Edward III at the siege of Berwick | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Up to 20,000 | Less than 10,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown. Surviving garrison capitulated and were allowed to leave | Very few | ||||||||

Location of the siege within Scotland | |||||||||

An advance force laid siege to the town in March. Edward III and the main English army joined it in May and pressed the attack. A large Scottish army advanced to relieve the town. After unsuccessfully manoeuvring for position and knowing that Berwick was on the verge of surrender, the Scots felt compelled to attack the English at Halidon Hill on 19 July. The Scots suffered a crushing defeat, and Berwick surrendered on terms the next day. Balliol was reinstalled as king of Scotland after ceding a large part of his territory to Edward III and agreeing to do homage for the balance.

Background

The First War of Scottish Independence between England and Scotland began in March 1296, when Edward I of England (r. 1272–1307) stormed and sacked the Scottish border town of Berwick as a prelude to his invasion of Scotland.[1] After 30 years of warfare that followed, the newly-crowned 14-year-old King Edward III was nearly captured in the English disaster at Stanhope Park. This brought his regents, Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer, to the negotiating table. They agreed to the Treaty of Northampton with Robert Bruce (r. 1306–1329) in 1328 but this treaty was widely resented in England and commonly known as turpis pax, "the cowards' peace". Some Scots nobles, refusing to swear fealty to Bruce, were disinherited and left Scotland to join forces with Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland (r. 1292–1296),[2] whom Edward I had deposed in 1296.[3]

Robert Bruce died in 1329; his heir was 5-year-old David II (r. 1329–1371). In 1331, under the leadership of Edward Balliol and Henry Beaumont, 4th Earl of Buchan, the disinherited Scottish nobles gathered in Yorkshire and plotted an invasion of Scotland. Edward III was aware of the scheme and officially forbade it, in March 1332 writing to his northern officials that anyone planning an invasion of Scotland was to be arrested. The reality was different, and Edward III was happy to cause trouble for his northern neighbour. He insisted that Balliol not invade Scotland overland from England but turned a blind eye to his forces sailing for Scotland from Yorkshire ports on 31 July 1332. The Scots were aware of the situation and were waiting for Balliol. David II's regent was an experienced old soldier, Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray. He had prepared for Balliol and Beaumont, but he died ten days before they sailed.[4][5]

Five days after landing in Fife, Balliol's force of some 2,000 men met the Scottish army of 12,000–15,000 men. The Scots were crushed at the Battle of Dupplin Moor. Thousands of Scots died, including much of the nobility of the realm. Balliol was crowned king of Scotland at Scone – the traditional place of coronation for Scottish monarchs[6] – on 24 September 1332.[3] Almost immediately, Balliol granted Edward III Scottish estates to a value of £2,000, which included "the town, castle and county of Berwick".[3] Balliol's support within Scotland was limited and within six months it had collapsed. He was ambushed by supporters of David II at the Battle of Annan a few months after his coronation. Balliol fled to England half-dressed and riding bareback. He appealed to Edward III for assistance.[7][8]

Prelude

Berwick, on the North Sea coast of Britain, is on the Anglo-Scottish border, astride the main invasion and trade route in either direction. In the Middle Ages, it was the gateway from Scotland to the English eastern march.[9] According to William Edington, a bishop and chancellor of England, Berwick was "so populous and of such commercial importance that it might rightly be called another Alexandria, whose riches were the sea and the water its walls".[10] It was the most successful trading town in Scotland, and the duty on wool which passed through it was the Scottish Crown's largest single source of income.[11] During centuries of war between the two nations its strategic value and relative wealth led to a succession of raids, sieges and takeovers.[12] Battles were rare, as the Scots preferred guerrilla tactics and border raiding into England.[13] Berwick had been sold to the Scots by Richard I of England (r. 1189–1199) 140 years before, to raise funds for his crusade.[14] The town was captured and sacked by Edward I in 1296, the first significant action of the First War of Scottish Independence.[15] Twenty-two years later Robert Bruce retook it after bribing an English guard, expelling the last English garrison from Scottish soil.[16] King Edward II of England (r. 1307–1327) attempted to recapture Berwick in 1319 but abandoned the siege after a Scottish army bypassed him and defeated a hastily assembled army under the Archbishop of York at the Battle of Myton.[17]

At the beginning of 1333, the atmosphere on the border was tense;[18] Edward III had dropped all pretence of neutrality, recognised Balliol as king of Scotland and was making ready for war.[19] The English parliament met at York and debated the situation for five days without conclusion. Edward III promised to discuss the matter with both Pope John XXII and King Philip VI of France (r. 1328–1350). Possibly to prevent the Scots from taking the initiative, England began openly preparing for war, while announcing that it was Scotland which was preparing to invade England.[20][21] In Scotland Archibald Douglas was Guardian of the Realm for the underage David. He was the brother of the "Good" Sir James Douglas, a hero of the First War of Independence. Weapons and supplies were gathered as he made arrangements for the defence of Berwick. Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March, the keeper of Berwick Castle, had recently spent nearly £200 on its defences. Sir Alexander Seton was appointed Governor of Berwick, responsible for the defence of the town.[22] After it was sacked in 1296, Edward I had replaced the old wooden palisade with stone walls. These were considerably improved by the Scots in 1318.[23] The walls stretched for 2 miles (3.2 kilometres) and were up to 40 inches (3 feet; 1 metre) thick and 22 feet (6.7 metres) high. They were protected by towers, each up to 60 feet (20 metres) tall.[24][note 1] The wall to the south-west was further protected by the River Tweed, which was crossed by a stone bridge and entered the town at a stone gatehouse. Berwick Castle was to the west of the town, separated by a broad moat, making the town and castle independent strongholds.[23] Berwick was well-defended, well-stocked with provisions and materiel, and expected to withstand a long siege.[26]

Siege

Balliol, in command of the disinherited Scottish lords and some English magnates, crossed the border on 10 March. Edward III made grants of over £1,000 to the nobles accompanying him on the campaign and a similar amount was paid to Balliol's companions; Balliol received over £700 personally.[27] He marched through Roxburghshire, burning and pillaging as he went and capturing Oxnam. He reached Berwick in late March and cut it off by land. Edward III's navy had already isolated it by sea. Balliol and the nobles accompanying him are said to have sworn not to withdraw until Berwick had fallen.[28] Edward arrived at Berwick with the main English army on 9 May,[29] after leaving Queen Philippa at Bamburgh Castle 15 miles (24 kilometres) south of Berwick.[30] Balliol had been at Berwick for six weeks and had placed the town under close siege. Trenches had been dug, the water supply cut and all communication with the hinterland prevented.[18][31] A scorched-earth policy was applied to the surrounding area to deny supplies for the town if an opportunity to break the siege occurred. The pillaging of the countryside also added to the English army's supplies.[31] The army included troops raised in the Welsh Marches and the Midlands, as well as levies from the north which had already mustered on account of the earlier Scottish raids. By the end of the month, this force had been augmented by noble retinues, a muster at Newcastle, and the assembly of the English fleet in the River Tyne.[32] Accompanying the army were craftsmen to build siege engines. Thirty-seven masons prepared nearly 700 stone missiles for the siege; these were transported by sea from Hull on 16 May.[33] Edward III had arranged for the combined army to be revictualled by sea through the small port of Tweedmouth.[32]

Douglas had assembled a large army north of the border but his inactivity contrasts sharply with Robert Bruce's swift response to the siege of 1319. Douglas seems to have spent the time assembling ever more troops, rather than using those he already had to mount diversionary raids.[18][34] Minor raids into Cumberland were launched by Sir Archibald Douglas. These were insufficient to draw the English forces from the siege. But it gave Edward III a pretext for his invasion, of which he took full advantage.[35] The success of Edward III's propaganda is reflected in contemporaneous English chronicles, which portray his invasion as retaliation against Scottish incursions,

… propter incursiones Scotorum cum incendijs ac multas alias illatas iniurias regno Anglie (… on account of the incursions of the Scots and the many injuries so inflicted on the realm of England).[36]

With the arrival of Edward III, the assault on Berwick began. It was commanded by the Flemish soldier-merchant John Crabb. Crabb had defended Berwick from the English in 1319, been captured by them in 1332 and now used his knowledge of Berwick's defences on England's behalf. Catapults and trebuchets were used to great effect.[18][37] The English used some form of firearms during the siege and modern historian Ranald Nicholson states that Berwick was probably "the first town in the British Isles to be bombarded by cannon".[38]

In late June, the defenders set adrift burning brushwood soaked in tar, in an attempt to repel a naval assault. Instead of the English ships, much of the town was set on fire.[39][40] William Seton, a son of the town's governor, was killed fighting an English seabourne assault.[41] By the end of June the attacks by land and sea had brought the town to a state of ruin and the garrison close to exhaustion.[18][37][note 2] It is believed that a desire for a respite from the plunging fire of the two large counterweight trebuchets used by the English was a significant factor in Seton requesting a short truce from King Edward.[33][37] This was granted, but only on the condition that he surrender if not relieved by 11 July. Seton's son, Thomas, was to be a hostage to the agreement, along with eleven others.[43][39]

Relief force

Douglas was now faced with a situation similar to that which the English had faced before the Battle of Bannockburn. Nicholson considers that "If Berwick were to be saved immediate action on the part of the Scottish guardian was unavoidable".[44] As a matter of national pride Douglas would have to come to the relief of Berwick, just as Edward II had come to the relief of Stirling Castle in 1314. The army that Douglas had spent so much time gathering was now compelled to take to the field.[18] The English army is estimated to have been less than 10,000 strong – outnumbered approximately two-to-one by the Scots.[45] Douglas entered England on 11 July, the last day of Seton's truce.[44] He advanced eastwards to Tweedmouth and destroyed it in sight of the English army. Edward III did not move.[18]

Sir William Keith, with Sir Alexander Gray and Sir William Prenderguest, led a force of around 200 Scottish cavalry. With some difficulty, they forced their way across the ruins of the bridge to the northern bank of the Tweed and made their way into the town.[34] Douglas considered the town relieved. He sent messages to Edward III calling on him to depart, threatening that if he failed to do so, the Scots army would devastate England. The Scots were challenged to do their worst.[46] The defenders argued that Keith's 200 horsemen constituted the relief according to the truce and therefore they did not have to surrender. Edward III stated that this was not the case: they had to be relieved directly from Scotland – literally from the direction of Scotland – whereas Keith, Gray and Prenderguest had approached Berwick from the direction of England.[47] Edward III ruled that the truce agreement had been breached – the town having neither surrendered nor been relieved. A gallows was constructed directly outside the town walls and, as the highest-ranking hostage, Thomas Seton was hanged while his parents watched. Edward III issued instructions that each day the town failed to surrender, another two hostages should be hanged.[47][note 3]

Keith, having taken command of the town from Seton, concluded a fresh truce on 15 July, promising to surrender if not relieved by sunset on 19 July.[18] The truce comprised two indentures, one between Edward III and the town of Berwick and the other between Edward III and March, the keeper of Berwick Castle. It defined circumstances in which relief would or would not occur. The terms of surrender were not unconditional. The town was to be returned to English soil and law but the inhabitants were to be allowed to leave, with their goods and chattels, under a safe conduct from Edward III. All members of the garrison would also be given free passage. Relief was defined as one of three events: 200 Scottish men-at-arms fighting their way into Berwick; the Scottish army forcing its way across a specific stretch of the River Tweed; or, defeat of the English army in open battle on Scottish soil. On concluding the new treaty, Keith was allowed to immediately leave Berwick, travel to wherever the Guardian of Scotland happened to be, advise him of the terms of the treaty, and return safely to Berwick.[48]

By this time Douglas had marched south to Bamburgh, where Edward III's queen Philippa was still staying, and besieged it; Douglas hoped that this would cause Edward III to break off his siege.[46] In 1319 Edward III's father, Edward II, had broken off a siege of Berwick after a Scottish army had advanced on York, where his queen was staying, and devastated Yorkshire.[49] However, whatever concerns Edward III had for his queen, he ignored the threat to Bamburgh.[50][46] The Scots did not have the time to construct the kind of equipment that would be necessary to take the fortress by assault. The Scots devastated the countryside but Edward III ignored this.[18] He positioned the English army on Halidon Hill, a small rise of some 600 feet (180 metres), 2 miles (3.2 km) to the north-west of Berwick, which gives an excellent view of the town and the vicinity. From this vantage point, he dominated the crossing of the Tweed specified in the indentures and would have been able to attack the flank of any force of men-at-arms attempting to enter Berwick. Receiving Keith's news, Douglas felt that his only option was to engage the English in battle.[48] Crossing the Tweed to the west of the English position, the Scottish army reached the town of Duns, 15 miles (24 km) from Berwick, on 18 July.[51] On the following day it approached Halidon Hill from the north-west, ready to give battle on ground chosen by Edward III.[18] Edward III had to face the Scottish army to the front and guard his rear against the risk of a sortie by the garrison of Berwick. By some accounts, a large proportion of the English army was left guarding Berwick.[52][53]

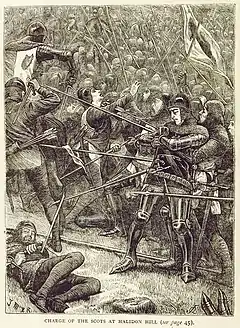

To engage the English, the Scots had to advance downhill, cross a large area of marshy ground and then climb the northern slope of Halidon Hill.[54][51] The Battle of Dupplin Moor the previous year had shown how vulnerable the Scots were to arrows. The prudent course of action would have been to withdraw and wait for a better opportunity to fight, but this would guarantee the loss of Berwick.[18][55] The armies encountered each other's scouts around midday on 19 July.[56] Douglas ordered an attack. The Lanercost Chronicle reports:

. . . the Scots who marched in the front were so wounded in the face and blinded by the multitude of English arrows that they could not help themselves, and soon began to turn their faces away from the blows of the arrows and fall.[58]

The Scots suffered many casualties and the lower reaches of the hill were littered with dead and wounded. The survivors continued upwards, through the arrows "as thick as motes in a sun beam", according to an unnamed contemporary quoted by Nicholson,[59] and on to the waiting spears.[59]

The Scottish army broke, the camp followers made off with the horses and the fugitives were pursued by the mounted English knights. The Scottish casualties numbered in thousands, including Douglas and five earls dead on the field.[18] Scots who surrendered were killed on Edward's orders and some drowned as they fled into the sea.[60] English casualties were reported as fourteen; some chronicles give a lower figure of seven.[61][62] About a hundred Scots who had been taken prisoner were beheaded the next morning, 20 July.[63] This was the date that Berwick's second truce expired, and the town and the castle surrendered on the terms in the indentures.[18][64]

Aftermath

After the capitulation of Berwick, Edward III appointed Baron Henry Percy as Constable, with Sir Thomas Grey (father of the chronicler Thomas Grey) as his deputy.[65] Considering his part done and short of money, he left for the south. On 19 June 1334, Balliol did homage to Edward for Scotland, after formally ceding to England the eight counties of south-east Scotland.[30] Balliol ruled a truncated Scottish state from Perth, from where he attempted to put down the remaining resistance. Seton in turn did homage to Balliol. Balliol was deposed again in 1334, restored again in 1335 and finally deposed in 1336, by those loyal to David II. Berwick was to remain the military and political headquarters of the English on the border until 1461, when it was returned to the Scottish by King Henry VI (r. 1422–1461).[66][67] Clifford Rogers states that Berwick "remained a bone of contention throughout the Middle Ages",[9] until its final re-capture for the English by the Duke of Gloucester, the future King Richard III, in 1482.[9]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- The surviving town walls are mostly of a later date and are considerably smaller than those of 1333.[25]

- The Brut Chronicle remarks that the English "made meny assautes with gonnes and with othere engynes to the toune, wherwith thai destroiede meny a fair hous; and cherches also were beten adoune unto the erthe, with gret stones, and spitouse comyng out of gonnes and of othere gynnes."[42] Later petitions from the town to the King also mention churches and houses having been "cast down" during the siege.[39]

- It has been suggested that Alexander Seton had little to lose: he had "already lost one son fighting against Balliol in 1332 and a second in the defence of the town [so] Sir Alexander Seton did not shrink from sacrificing a third".[47]

- Based on Sumption.[57]

Citations

- Barrow 1965, pp. 99–100.

- Weir 2006, p. 314.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 19.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 124, 126.

- DeVries 1996, p. 116.

- Rodwell 2013, p. 25.

- Wyntourn 1907, p. 395.

- Maxwell 1913, pp. 274–275.

- Rogers 2010, p. 144.

- Robson 2007, p. 234.

- Ormrod 2012, p. 161.

- MacDonald Fraser 1971, p. 38.

- Prestwich 1988, p. 469.

- Geldard 2009, p. 58.

- Prestwich 1988, p. 471.

- Brown 2008, p. 151.

- Bradbury 2004, p. 216.

- Sumption 1990, p. 130.

- Sumption 1990, p. 12.

- McKisack 1991, p. 117.

- Nicholson 1961, pp. 20–21.

- Nicholson 1961, pp. 22–23.

- Blackenstall 2010, p. 11.

- Forster 1907, p. 97.

- Pettifer 2002, p. 176.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 23.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 21.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 22.

- Maxwell 1913, pp. 278–279.

- Ormrod 2008.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 26.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 24.

- Corfis & Wolfe 1999, p. 267.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 29.

- Nicholson 1961, pp. 23–24.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 24, n. 2.

- Hall 1999, p. 267.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 27.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 28.

- Rogers 2010, p. 145.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 31, n. 4.

- Brie 1960, p. 281.

- Dalrymple 1819, pp. 374–375.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 29, n. 2.

- Ormrod 2012, p. 159.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 30.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 31.

- Nicholson 1961, pp. 32–33.

- Prestwich 2003, p. 51.

- DeVries 1996, p. 114.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 36.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 35.

- Oman 1998, p. 106.

- Stock 1888, pp. 54–55.

- Stock 1888, p. 54.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 37.

- Sumption 1990, p. 131.

- Maxwell 1913, p. 279.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 39.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 41.

- Strickland & Hardy 2011, p. 188.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 42.

- King 2002, p. 281.

- Tuck 2002, p. 148.

- Maxwell 1913, pp. 282–283.

- Nicholson 1974, p. 129.

- Maurer 2003, p. 204.

Sources

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1965). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. OCLC 655056131.

- Blackenstall, Stan (2010). Coastal Castles of Northumberland. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-44560-196-0.

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge Companions to History. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41522-126-9.

- Brie, Friedrich (1960). The Brut; or, The Chronicles of England. Early English Text Society (repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 15591643.

- Brown, Michael (2008). Bannockburn. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3333-3.

- Corfis, Ivy; Wolfe, Michael (1999). The Medieval City Under Siege. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-756-6.

- Dalrymple, Sir David (1819). Annals of Scotland: From the Accession of Malcolm III. in the Year M.LVII. to the Accession of the House of Stewart in the Year M.CCC.LXXI. To which are Added, Tracts Relative to the History & Antiquities of Scotland. 2. Edinburgh: A. Constable & Co. OCLC 150903449.

- DeVries, Kelly (1996). Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century : Discipline, Tactics, and Technology. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-571-5.

- Forster, Robert Henry (1907). "The Walls of Berwick-upon-Tweed". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. XIII (2): 89–104. doi:10.1080/00681288.1907.11894053. ISSN 0068-1288.

- Geldard, Ed (2009). Northumberland Strongholds. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-71122-985-3.

- Hall, Bert (1999). "Technology and Tactics". In Corfis, Ivy; Wolfe, Michael (eds.). The Medieval City Under Siege. Medieval Archaeology Series. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 257–276. ISBN 978-0-85115-756-6.

- King, Andy (2002). "According to the Custom Used in French and Scottish Wars: Prisoners and Casualties on the Scottish Marches in the Fourteenth Century". Journal of Medieval History. XXVIII (3): 263–290. doi:10.1016/S0048-721X(02)00057-X. ISSN 0304-4181. S2CID 159873083.

- MacDonald Fraser, George (1971). The Steel Bonnets. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00272-746-4.

- Maurer, Helen Estelle (2003). Margaret of Anjou: Queenship and Power in Late Medieval England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-927-0.

- Maxwell, Herbert (1913). The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346. Glasgow: J. Maclehose. OCLC 27639133.

- McKisack, May (1991). The Fourteenth Century (repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19285-250-2.

- Nicholson, Ranald (1961). "The Siege of Berwick, 1333". The Scottish Historical Review. XXXX (129): 19–42. JSTOR 25526630. OCLC 664601468.

- Nicholson, Ranald (1974). Scotland: The Later Middle Ages. University of Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. ISBN 978-0-05002-038-8.

- Oman, Charles (1998) [1924]. A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages: 1278–1485 A.D. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-332-0.

- Ormrod, Mark (2008). "War in Scotland, 1332–1336". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8519. Retrieved 6 December 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Ormrod, Mark (2012). Edward III. Yale Medieval Monarchs series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11910-7.

- Pettifer, Adrian (2002). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Prestwich, Michael (1988). Edward I. Yale Medieval Monarchs series. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52006-266-5.

- Prestwich, Michael (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377 (2nd ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robson, Eric (2007). The Border Line. London: Frances Lincoln Publishers. ISBN 978-0-71122-716-3.

- Rodwell, Warwick (2013). The Coronation Chair and Stone of Scone: History, Archaeology and Conservation. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78297-153-5.

- Rogers, Clifford (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19533-403-6.

- Stock, John (1888). Berwick-upon-Tweed. The history of the town and guild. London: E Stock. OCLC 657093471.

- Strickland, Matthew; Hardy, Robert (2011). The Great Warbow: From Hastings to the Mary Rose. Somerset: J. H. Haynes & Co. ISBN 978-0-85733-090-1.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1990). Trial by Battle. The Hundred Years' War. I. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-57120-095-5.

- Tuck, Anthony (2002). "A Medieval Tax Haven: Berwick upon Tweed and the English Crown, 1333–1461". In Britnel, Richard; Hatcher, John (eds.). Progress and Problems in Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Edward Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–167. ISBN 978-0-52152-273-1.

- Weir, Alison (2006). Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-34545-320-4. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Wyntourn, Andrew (1907). Amours, François Joseph (ed.). The Original Chronicle of Scotland. II. Edinburgh: Blackwood. OCLC 61938371.