Siege of Dundee

The Siege of Dundee took place from 30 August to 1 September 1651 (plus around three days in aftermath). A decisive victory for General Monck representing Oliver Cromwell, it was the final battle of the English Civil War on Scottish soil.

| Siege of Dundee (1651) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Wars of the Three Kingdoms | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

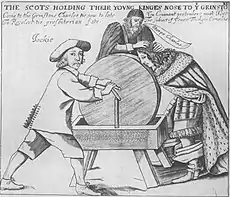

In 1639, and again in 1640, Charles I, who was king of both Scotland and England in a personal union, went to war with his Scottish subjects in the Bishops' Wars. These had arisen from the Scots' refusal to accept Charles's attempts to reform the Scottish Kirk to bring it into line with English religious practices.[1] Charles was not successful and after years of rising tensions, in part caused by Charles's defeat in the Bishops' Wars and his need to fund them, the relationship between Charles and his English Parliament also broke down in armed conflict, starting the First English Civil War in 1642.[2][3]

In England Charles's supporters, the Royalists, were opposed by the combined forces of the Parliamentarians and the Scots, who in 1643 had formed an alliance bound by the Solemn League and Covenant, in which the English Parliament agreed to reform the English church along similar lines to the Scottish Kirk in return for the Scots' military assistance.[4] After four years of war the Royalists were defeated and Charles surrendered to the Scots.[5] After several months of fruitless negotiations the Scots handed Charles over to the English parliamentary forces in exchange for a financial settlement, and left England on 3 February 1647.[6]

Exasperated by Charles' intransigence and the prolonged bloodshed, the New Model Army purged the English Parliament and established the Rump Parliament, which had Charles tried for treason against the English people. He was executed on 30 January 1649,[7] and the republican Commonwealth was created. [8] The Scottish Parliament, which had not been consulted prior to the King's execution, declared his son, also Charles, king of Britain. [9][10] Charles II was initially reluctant to accept the conditions attached to this declaration, but after Cromwell's campaign in Ireland crushed his Royalist supporters there,[11] he felt compelled to accept the Scottish terms. The Scottish Parliament set about rapidly recruiting an army to support the new king,[12] under the command of the experienced general David Leslie. [12]

Scotland was actively rearming and the leaders of the English Commonwealth felt threatened. [13] Oliver Cromwell was appointed commander-in-chief of the New Model Army and led it across the Tweed into Scotland on 22 July 1650, so starting the Third English Civil War. [14] Cromwell manoeuvred around Edinburgh, attempting to bring the Scots to battle, but he was not able to draw Leslie out. [15] On 31 August Cromwell withdrew; [16] to Dunbar. [17][18] Believing the English army was in a hopeless situation and under pressure to finish it off rapidly,[19][20] Leslie moved his into a position to attack Dunbar. [21][17] On the night of 2/3 September Cromwell manoeuvred his army so as to be able to launch a concentrated pre-dawn attack against the Scottish right wing. [22][23] The battle was undecided when Cromwell personally led his cavalry reserve in a flank attack on the two Scottish infantry brigades which had managed to come to grips with the English and rolled up the Scottish line. [24][25] Leslie executed a fighting withdrawal, but some 6,000 Scots, from his army of 12,000, were taken prisoner, and approximately 1,500 killed or wounded. [26][27]

Leslie sought to rally what remained of his army, and build a new defensive line at Stirling. This was a narrow choke point which blocked access to north-east Scotland, the major source of supplies and recruits for the Scots. There he was joined by the bulk of the government, clergy, and Edinburgh's mercantile elite. [28] On 1 January 1651 Charles was formally crowned at Scone. [29] In early February the English army advanced against Stirling, then retreated in dreadful weather; Cromwell himself fell ill. [30] In late June the Scottish army advanced south. The English moved north from Edinburgh to meet them and the Scots eventually withdrew. Cromwell followed and attempted to bypass Stirling, but was unable to. [31]

Late in 1650 the Council of State, the executive authority of the English Commonwealth, ordered the construction of 50 flat-bottomed boats, which arrived in Leith in June 1651. [32] The Scots anticipated the possibility of another attempt to cross the Forth and established a garrison at Burntisland. [33] Early on 17 July,[33] an English force of 1,600 men[34] crossed the Firth of Forth at its narrowest point, landing at North Queensferry on the Ferry Peninsula. The Scottish troops at Burntisland moved towards the English landing place, sent for reinforcements from Stirling and Dunfermline, and dug in to await them. For the next four days the English shipped the balance of their own force across the Forth. [33][34] They totalled approximately 4,000 men. [35] The modern historian Austin Woolrych states the Scots had more than 4,000 men. [35] On 20 July the Scots advanced on the English. [36]

The Scottish cavalry on both flanks charged and initiallly got the better of the English cavalry. The English had maintained a reserve, which counter-charged the disordered Scots, routing them.[37] With the battle lost, the Scottish infantry attempted to retreat from the field. They were pursued by the English cavalry for 6 miles (9.7 km).[38][39] Sir James Balfour, a senior officer in the Scottish army, wrote in his journal that about 800 Scots were killed in total. [40] Modern sources believe that approximately 1,000 Scots were captured. [41]

Prelude

After the battle, Lambert marched 6 miles (10 km) east and occupied the deep-water port of Burntisland[32] and Cromwell shipped most of the English army there.[38] Realising this left open the way into England for the Scots, Cromwell issued contingency orders as to what measures to take if this were to occur.[38][35] He then ignored the Scottish army at Stirling and on 31 July marched on the seat of the Scottish government at Perth, which he besieged. Perth surrendered after two days, cutting off the Scottish army from reinforcements, provisions and materiel.[32][42] Charles and Leslie could not resist the lure of a march into England and took their army south. Cromwell and Lambert followed, shadowing the Scottish army, while leaving General George Monck with 6,000 of the least experienced men to mop up what Scottish resistance remained.[43]

By the end of August, Monck had captured Stirling, Alyth, and St Andrews. Dundee and Aberdeen were the last significant Scottish strongholds. Monck drew up his full army outside Dundee on 26 August and demanded its surrender. Following the English victory at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 Scottish towns feared English invasion and many built defensive walls. Those of Dundee dated from 1545 and was remarkably entire in comparison to other Scottish towns.[44] In the mid-17th century Dundee was a compact and well-defended town, with a town wall to west, north and east and the Tay Estuary to the south. It had a good harbour and links to Aberdeen and Edinburgh by sea were excellent. Roads by comparison were poor. The town wall had three gates (ports) on each of its three sides, the main gate being to the west to connect to Perth.[45] The town was dominated by Dundee Law a hill to the north of the town wall. Inside the wall a spired church (St Mary's) standing on a small hill dominated the townscape.[46] Due to the unsettled times and the perceived security of Dundee in relation to other Scottish cities, it was used as a storehouse for Scottish gold, and this fact was known to the English.[47]

The siege

General Monck had moved a substantial force (probably around 5,000 to 7,000) including cavalry, artillery and siege mortars, to encircle Dundee in August 1651, following their success in the surrender of Stirling Castle. This movement was at least partially by sea, and was clearly visible to the citizens of Dundee.[48] In the mid-17th century Dundee was a compact and well-defended town, with a town wall to west, north and east and the Tay Estuary to the south. It had a good harbour and links to Aberdeen and Edinburgh by sea were excellent. Roads by comparison were poor. The town wall had three gates (ports) on each of its three sides, the main gate being to the west to connect to Perth.[49] The town was dominated by Dundee Law a hill to the north of the town wall. Inside the wall a spired church (St Mary's) standing on a small hill dominated the townscape.[50] Due to the unsettled times and the perceived security of Dundee in relation to other Scottish cities, it was used as a storehouse for Scottish gold, and this fact was known to the English.[51]

The Scots had opportunity to bring other local troops into Dundee to defend the town including cavalry regiments controlled by Lt Col John Leslie.[52] Dundee had a barracks (in the west of the town) but the total number of troops was certainly below 1000. Six small armed ships belonging to the Royalists lay in Dundee Harbour, but these could not fire on the outer sides of the town wall as this would be firing across Dundee itself. Defence of the town fell on the town barracks and to a number of armed volunteers from surrounding estates. Although cavalry was present this was of limited or perhaps no value, within the closed walls.

General Monck had everything in place by 26 August and sent a written demand for surrender to the governor Robert Lumsden, fully expecting his capitulation in the circumstances. Lumsden however was unduly confident that the town's walls were secure and refused to surrender. Monck was infuriated and not only began his bombardment but also instructed his troops that once they were within the walls that they may murder and plunder as they pleased. Within this instruction there was a general understanding that the army would loot the large quantity of Scottish gold held in Dundee.[53]

The use of cannon and mortars began on 29 August and was concentrated on the town gates. The town refused to surrender, being confident their walls would hold. However, three days of bombardment continued.[53] Stories regarding the Dundee garrison being drunk hold little weight as (drunk or not) this was not a surprise attack, and the defenders were expecting a fight.[54] At 4 am on 1 September the surrounding army began their final assault, including use of mortar. At 11 am the west and east ports were breached and the defending force retreated to the main church. The battle then focussed upon the attack of the church (now known as the Steeple Church).[55] By the conventions of the day, the resistance of the garrison meant that "no quarter" was given by the attacking troops and a massacre ensued.[56]

The most believable account is the contemporary diary of John Lamont, which put English casualties at only 20 (and only one officer: Captain Hart) but Scottish casualties at 500 to 600, including militia, soldiers, townsfolk and "strangers". English estimates went up to 1100 killed.[57] A further 500 (*presumably soldiers) were taken prisoner. This in total equates to the entire military force of Dundee. The townsfolk loss was considerable but statistically could not exceed 200.[58] The population of Dundee at this time is not accurately recorded but comparing to other known towns would be between 5000 and 10000. Modern accounts of one third of the town being killed are therefore gross exaggeration.[54] 500 prisoners were taken (which was the residue of the military force). This included Col Coningham, previously the military governor of Stirling castle. The Military Governor of Dundee, Robert Lumsden or Lumsdaine of Balwhinnie (or Montquhinnie) was certainly killed, Contemporary accounts say he was killed in the battle for the church. Later accounts say he was singled out for punishment as a public example and beheaded in the town centre.[53]

Around 200,000 gold coins were plundered, with a 21st-century value of around £12 billion. The English also captured the ships in the harbour six of which were armed with cannon (40 cannon in total, the largest ship being ten-gun). And 190 sail (ships were counted in sails) totalling around 60 ships.[53] The large number of dead were buried in mass graves on 3 September. Deaths from wounds would presumably continue for around a month. Stories that the bodies were buried in the earth roads are perhaps true as there is no evidence of mass graves in the churchyard, nor would this huge number be capable of containment. The harbour fleet was used to transport the huge haul of gold to England. Whilst stories as to the fate of the ships vary, all agree the ships did not reach their destination, and sank either due to storm, or other disaster, in the Tay Estuary. This may be seen as poetic justice.[59]

Aftermath

The English army occupied Dundee for nine years after the siege. Dundee never recovered its former position.[60] Not until December 1669 did the Scottish Parliament vote monies to repair the damage done in Dundee. They placed the cost of the damage at 100,000 Scots pounds. This excluded the robbery of gold, which if true was one of the largest thefts ever in British history.[61]

On 3 September 1651 (two days later) the New Model Army won a decisive victory over the Royalist army at Worcester: the final battle of the English Civil War. The shift of power in England moved permanently to the Parliament rather than the Crown.[62]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

Citations

- Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2002, pp. 15–16.

- Rodger 2004, pp. 413–415.

- Woolrych 2002, p. 229–230.

- Woolrych 2002, p. 271.

- Woolrych 2002, pp. 329–330.

- Woolrych 2002, pp. 340–349.

- Woolrych 2002, pp. 430–433.

- Gentles 2002, p. 154.

- Dow 1979, p. 7.

- Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2002, p. 32.

- Ohlmeyer 2002, pp. 98–102.

- Furgol 2002, p. 65.

- Woolrych 2002, p. 482.

- Dow 1979, p. 8.

- Woolrych 2002, pp. 484–485.

- Edwards 2002, p. 258.

- Brooks 2005, p. 514.

- Reese 2006, p. 68.

- Royle 2005, p. 579.

- Reid 2008, p. 57.

- Wanklyn 2019, p. 138.

- Brooks 2005, p. 516.

- Royle 2005, p. 581.

- Reese 2006, pp. 96–97.

- Reid 2008, pp. 74–75.

- Brooks 2005, p. 515.

- Reid 2008, pp. 39, 75–77.

- Woolrych 2002, p. 487.

- Reid 2008, p. 84.

- Reid 2008, pp. 82, 84.

- Reid 2008, p. 85.

- Wanklyn 2019, p. 140.

- Reid 2008, pp. 85–86.

- Ashley 1954, p. 51.

- Woolrych 2002, p. 494.

- Reid 2008, pp. 86, 88–89.

- Reid 2008, p. 89.

- Reese 2006, p. 116.

- Reid 2008, pp. 87, 89.

- Reid 2008, pp. 90–91.

- Stewart 2020, p. 176.

- Reid 2008, p. 91.

- Woolrych 2002, pp. 494–496.

- "Dundee Feature Page on Undiscovered Scotland". www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk.

- "Photo". monikie.org.uk. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "View: Dundee – 'The Prospect of ye Town of Dundee' – John Slezer's Engravings of Scotland". maps.nls.uk.

- "17th century Archives".

- "General George Monck – Home Page". www.generalmonck.com.

- "Photo". monikie.org.uk. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "View: Dundee – 'The Prospect of ye Town of Dundee' – John Slezer's Engravings of Scotland". maps.nls.uk.

- "17th century Archives".

- ODNB: John Leslie

- "The Storming of Dundee". 3 September 2014.

- Dundee Evening Telegraph 18 Sept 2013

- Scots Magazine 11 May 2015

- Wainwright, Brian (14 January 2012). "English Historical Fiction Authors: General George Monck and the Siege of Dundee".

- "1645 Seige of Dundee [sic]". FDCA. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Diary of John Lamont 1 September 1651

- Scotsman newspaper 3 August 2002

- "BBC – History – British History in depth: Scottish Wars of Independence". www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Records of the Parliaments of Scotland". www.rps.ac.uk.

- "The Battle of Worcester, 1651". Historic UK.

Sources

- Ashley, Maurice (1954). Cromwell's Generals. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 557043110.

- Brooks, Richard (2005). Cassell's Battlefields of Britain and Ireland. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-304-36333-9.

- Dow, F.D. (1979). Cromwellian Scotland 1651-1660. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85976-049-2.

- Edwards, Peter (2002). "Logistics and Supply". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 234–271. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Furgol, Edward (2002). "The Civil Wars in Scotland". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 41–72. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Gentles, Ian (2002). "The Civil Wars in England". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 103–154. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Hutton, Ronald & Reeves, Wiley (2002). "Sieges and Fortifications". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 195–233. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (2002). "The Background to the Civil Wars in the Stuart Kingdoms". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–40. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Ohlmeyer, Jane (2002). "The Civil Wars in Ireland". In Kenyon, John & Ohlmeyer, Jane (eds.). The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland 1638–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–102. ISBN 978-0-19-280278-1.

- Reese, Peter (2006). Cromwell's Masterstroke: The Battle of Dunbar 1650. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-179-0.

- Reid, Stuart (2008) [2004]. Dunbar 1650: Cromwell's Most Famous Victory. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-774-1.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Safeguard of the Sea. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-029724-9.

- Royle, Trevor (2005) [2004]. Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, 1638–1660. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- Stewart, Laura A. M. (2020). Union, Revolution and War: Scotland 1625–1745. The New History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1015-1.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm (2019). Parliament's Generals: Supreme Command and Politics During the British Wars 1642–51. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-47389-836-3.

- Woolrych, Austin (2002). Britain in Revolution 1625–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820081-9.