Siege of Fort Macon

The Siege of Fort Macon took place from March 23 to April 26, 1862, on the Outer Banks of Carteret County, North Carolina. It was part of Union Army General Ambrose E. Burnside's North Carolina Expedition during the American Civil War.

| Siege of Fort Macon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Fort Macon, NC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

John G. Parke Samuel Lockwood [1] | Moses J. White [1] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

3rd Division, Department of North Carolina North Atlantic Blockading Squadron [1] | Fort Macon Garrison [1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,259 total 2,649 present for duty [2] |

450 total 263 ready for duty [3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 killed 5 wounded 8 captured [4] |

8 killed 16 wounded ~400 captured[5] | ||||||

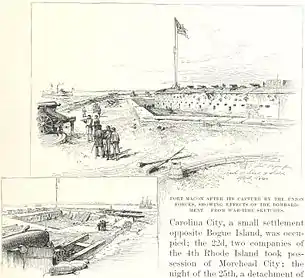

In late March, Major General Burnside’s army advanced on Fort Macon, a casemated masonry fort that commanded the channel to Beaufort, 35 miles (56 km) southeast of New Bern. The Union force invested the fort with siege works and on April 25 opened an accurate fire on the fort, soon breaching the masonry walls. Within a few hours the fort's scarp began to collapse, and in late afternoon the Confederate commander, Colonel Moses J. White, ordered the raising of a white flag. Burnside's terms of surrender were accepted, and the Federal troops took possession of the fort the next morning.

Background

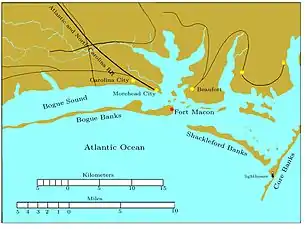

Fort Macon was one of the Third System coastal forts that were built around the borders of the still-young United States following the War of 1812. It was built on the eastern end of Bogue Banks, in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and was intended to defend the entrance to the ports of Beaufort and Morehead City. Begun in 1826, it was completed and received its first garrison in 1834. As it was intended for defense against attacking enemy naval forces, it was built of masonry. Gunfire from a rolling ship's deck was not accurate enough at that time to be able to break down brick and stone walls. Although the advent of rifled artillery would soon make its walls vulnerable, no alterations were made in the fort. It was a generation out of date when the Civil War came.[6]

After the first spate of enthusiasm, the fort was allowed to deteriorate. The woodwork rotted, the ironwork rusted, and gun carriages were allowed to decay. The garrison was steadily reduced in size, until by the time of the beginning of the Civil War the care of the fort was entrusted to a single sergeant.[7] When the fort was taken over by North Carolina troops under Captain Josiah Solomon Pender on April 14 (before the state had seceded from the Union), only four guns were mounted. The local military authorities immediately set about improving the armament. A total of 56 pieces (5 8-inch and 2 10-inch columbiads, 19 24-pounders, 32 32-pounders, and 6 field guns) were mounted, but they had ammunition for only three days of action.[8]

At the time of the siege, the garrison of the fort numbered about 430 officers and men, commanded by Colonel Moses J. White. Sickness reduced this number by about a third. Despite the poor diet and other living conditions that they suffered, only one man died. Morale among the men was generally not good, as they were cut off from their families, and White was unpopular, both with his men and with the people of Beaufort. A few men deserted during the siege.[9]

When battle came, the fort was outdated, inadequately armed, poorly supplied, and intended for a different form of combat than that it faced. These deficiencies are adequate to explain why the fort succumbed so readily at the first blow.

Prelude

Shortly after the Union forces had taken possession of Hatteras Island on the Outer Banks, Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside developed a plan to expand Federal control of eastern North Carolina by a joint Army-Navy expedition. His plan was approved by General-in-Chief George B. McClellan and the War Department. He was given authority to recruit and organize a division, to be known as the Coast Division, which would work with the Navy's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron to take control of the North Carolina Sounds and their adjacent cities. The expedition that came to be known by his name got under way in January 1862, and in early February had made its first conquest, Roanoke Island. Following that, the joint forces went on to other victories at Elizabeth City and New Bern (often spelled New Berne at the time). Most of the Confederate Army were forced away from the coast as far inland as Kinston by these battles. The major exception was the garrison of Fort Macon.[10]

So long as Fort Macon remained in Confederate possession, Burnside (recently promoted to rank of major general) could not use the ports at Beaufort and Morehead City, so immediately following the capture of New Bern on March 14, he ordered Brigadier General John G. Parke, commander of his Third Brigade, to reduce the fort. Parke began by seizing the towns along the inner shore: Carolina City on March 21, Morehead City on March 22, Newport on March 23, and finally Beaufort on March 25. Communications between the garrison and other Confederate forces were thereby severed.[11] Parke also had to repair a railroad bridge at Newport, burned by the retreating Confederates following the loss of New Bern; the railroad was needed for the transport of his siege artillery.[12]

Siege

On March 23, General Parke sent a message from his headquarters at Carolina City to Colonel White, demanding the surrender of the fort. He offered to release the men on parole if the fort was turned over intact. White replied tersely, "I have the honor to decline evacuating Fort Macon." [13] The siege can be regarded as starting with this exchange.

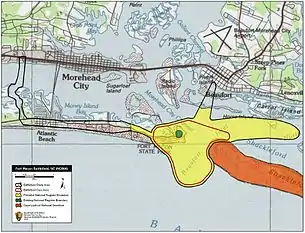

The investment of the fort was not yet complete, but that was accomplished on March 29, when a company from Parke's brigade crossed the sound and landed unopposed on Bogue Banks. The Confederate infantry that would have defended against the landing, the 26th North Carolina, had been included in the retreat following the Battle of New Bern.[14] Federal siege artillery followed, and Parke set up four batteries that would bear on the fort: four 8-inch (20.3 cm) mortars at a range of 1200 yards (1100 meters); four 10-inch (25.4 cm) mortars at a range of 1600 yards (1460 meters); three 30-pounder (13.6 kg) rifled Parrotts at a range of 1300 yards (1190 meters); and a 12-pounder (5.4 kg) boat howitzer at a range of 1200 yards (1100 meters).[15] The batteries were moved up at night and remained hidden behind sand dunes until they were ready to open fire. The defenders were aware of these activities, but could not waste ammunition by firing at unseen targets. Patrols sent out from the fort to harass the Union soldiers were driven back, usually without loss. On April 17, General Burnside could state in his report to the War Department, "I hope to reduce the fort within ten days."[16] His prediction proved to be remarkably accurate.

Preparations were completed by April 23, and on that day General Burnside communicated directly with Colonel White and repeated his demand for surrender, again offering to release the prisoners on parole.[17] Colonel White once more refused, so Burnside on April 24 ordered General Parke to begin the bombardment as soon as possible. Parke waited until nightfall to open the embrasures for his guns behind the dunes. The bombardment began at dawn on April 25. At first, the gunners in the fort manned their pieces and replied vigorously, but they were unable to inflict damage on the Federal guns protected by the dunes.[18]

The defenders were also distracted by the appearance of four vessels from the Blockading Squadron: the steamers USS Daylight, State of Georgia, and Chippewa, and the bark Gemsbok. Until this time, the Navy had not been involved with the siege, but Commander Samuel Lockwood responded to the sound of gunfire and brought his section of the fleet into action. The weather was not good for a naval bombardment, however; a strong wind created waves that caused the vessels to rock badly enough to disrupt their aim, and after about an hour, the fleet withdrew. The Navy also supplied a pair of floating batteries to the attack, but again the waves interfered, and only one of them got into action. It is not certain whether the fort sustained any hits from the ships. The Confederate return fire was accurate enough to hit two vessels, doing little damage and slightly wounding only one man.[19]

The initial fire from the mortars on shore was inaccurate, but a Signal Corps officer in Beaufort, Lieutenant William J. Andrews, acting on his own responsibility, was able to deliver messages to the battery commanders telling them how to adjust their range. After noon, virtually all shots were on target.[20] Nineteen guns were dismounted.[21] The walls of the fort began to crumble under the continued pounding, and in mid-afternoon Colonel White began to fear that the magazine would be breached. At 4:30 p.m., he decided that the fort could no longer hold out, so he ordered that a white flag be raised. Firing on both sides then ceased.[22]

Colonel White met with General Parke to discuss terms, and Parke at first demanded unconditional surrender. White asked him for more favorable conditions, and referred to the terms that General Burnside had offered on March 23. Parke did not concede, but agreed not to renew the bombardment until he could consult with Burnside. Burnside reasoned that White could hold out at least one more day, and further action would only cause more casualties and greater damage to the fort. He therefore agreed to adhere to his first terms. The men in the fort were allowed to give their paroles, meaning that they would not take up arms against the United States until properly exchanged. They then were permitted to return to their homes, taking with them their personal property. Shortly after dawn on April 26, the Confederate flag was lowered, the defenders marched out, and Union soldiers of the 5th Rhode Island marched in.[23]

Aftermath

The battle had been relatively bloodless, at least by standards that soon would be common in the Civil War. On the Union side, only one man was killed, and two soldiers and one seaman were wounded. On the Confederate side, seven were killed outright, two died of wounds, and sixteen were wounded.[24]

Although the Burnside Expedition had gained notable success at little cost in North Carolina, little was done to exploit it. Wilmington, for example, would seem to have been vulnerable, but it was not attacked until the final days of the war. Burnside was recalled shortly after the victory at Fort Macon, to assist General George B. McClellan in the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia. No further major offensive actions took place, and North Carolina became a secondary theater until late in the war. The flag was returned to the State of North Carolina in 1906, in a Senate Chamber ceremony attended by veterans of the siege. The battle site is now Fort Macon State Park.

See also

Notes

Abbreviations used in these notes:

- ORA (Official records, armies): War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

- ORN (Official records, navies): Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

- CWSAC Report Update

- ORA I, v. 9, p. 381)

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 141.

- ORA I, v. 9, pp. 272, 281, 295.

- ORA I, v. 9, p. 294.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, pp. 133–134.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 134. Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, p. 35.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, pp. 10, 135–136. Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, p. 35, says that only 43 guns were mounted. Burnside says in his report that 54 were taken. ORA I, vol. 9, p. 275.

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 293. Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 138.

- Burnside, Battles and leaders, vol. 1, pp. 660–669.

- Hawkins, Battles and leaders, vol. 1, pp. 652–653.

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 277.

- ORA I, v. 9, pp. 277, 278. Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 137.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 135.

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 273,

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 270.

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 275.

- ORA I, v. 9, pp. 273–274.

- ORN I, vol. 7, p. 279.

- ORA I, vol. 9, pp. 291–292. Trotter, ``Ironclads and columbiads, p. 143.

- ORA I, v. 9, pp. 288, 290. White in his report says that 15 were disabled, p. 294.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, pp. 144–145.

- ORA I, vol. 9, p. 275. Hawkins, Battles and leaders, vol. 1, p. 654.

- Trotter, Ironclads and columbiads, p. 145.

References

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Univ. of Alabama, 1993. ISBN 0-8173-5019-5

- Campbell, R. Thomas, Storm over Carolina: the Confederate Navy's struggle for eastern North Carolina. Cumberland House, 2005. ISBN 1-58182-486-6

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence Clough Buel, Battles and leaders of the Civil War. Century, 1887, 1888; reprint ed., Castle, n.d.

- Burnside, Ambrose E., "The Burnside Expedition," pp. 660–669.

- Hawkins, Rush C., "Early coast operations in North Carolina," pp. 652–654.

- Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-4696-4972-6.

- Trotter, William R., Ironclads and columbiads: the coast. Joseph F. Blair, 1989. ISBN 0-89587-088-6

- Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922.

- Ser. I, vol. 7, pp.277–283.

- A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I: 53 volumes. Series II: 8 volumes. Series III: 5 volumes. Series IV: 4 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1886–1901.The War of the Rebellion

- Ser. I, vol. 9, pp. 270–294.

- National Park Service Battle Summary

- CWSAC Report Update

- The farmer and mechanic.(Raleigh, N.C.), 06 March 1906. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.Retrieved 2016-07-20.

.svg.png.webp)