Siege of Krujë (1466–1467)

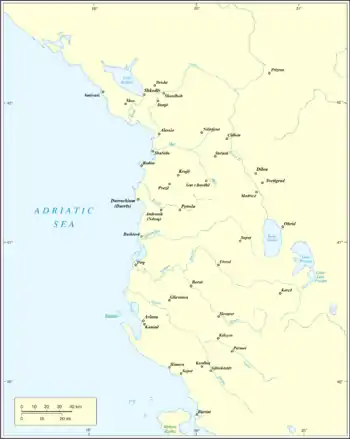

The second siege of Krujë took place from 1466 to 1467. Sultan Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire led an army into Albania to defeat Skanderbeg, the leader of the League of Lezhë, which was created in 1444 after he began his war against the Ottomans. During the almost year-long siege, Skanderbeg's main fortress, Krujë, withstood the siege while Skanderbeg roamed Albania to gather forces and facilitate the flight of refugees from the civilian areas that were attacked by the Ottomans. Krujë managed to withstand the siege put on it by Ballaban Badera, sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Ohrid, an Albanian brought up in the Ottoman army through the devşirme. By 23 April 1467, the Ottoman army had been defeated and Skanderbeg entered Krujë.

| Second siege of Krujë | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman Wars in Europe | |||||||

Second Siege of Krujë 1466 - Engraving by Jost Amman 1587 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13,400 men | 30,000–100,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| low | heavy | ||||||

Mehmed had decided to construct a fortress in what is now Elbasan which would provide a perennial base for future Ottoman assaults on Skanderbeg's domains. The fortress especially worried Venice since Elbasan was constructed on the banks of the Shkumbin River which would allow the Ottomans to send ships into the Adriatic and threaten Venetian colonies. Seeing that his situation had become unfavorable, Skanderbeg made a trip to Italy where he would try to convince Pope Paul II and Ferdinand I of Naples to give him aid for his war. Despite many promises from the pope, Skanderbeg received little due to the fear of a Neapolitan war with Rome and infighting in the Roman Curia. Ferdinand and the Republic of Venice likewise deferred Skanderbeg's requests to the pope. By the time he left Italy, the League of Lezhë had been weakened and needed his intervention.

After his return the Venetians decided to send troops against the Ottoman advances. Skanderbeg gathered 13,400 men, among whom were many Venetians, to launch an assault on the Ottoman besieging camp, who had taken command once Mehmed left Albania after the construction of Elbasan. Skanderbeg had split his army into three parts and surrounded the besiegers. Ballaban was killed during the fighting and the Ottoman forces were left without a commander and a depleted force which was surrounded. Afterwards the Albanian-Venetian forces completed the rout by killing the remaining Ottoman forces before they could escape by way of Dibër. The victory was well received by both Albanians and Italians. This did not signal the end of the war, however, as soon after, Skanderbeg took up some assaults on Elbasan after being urged to by Venice, but was not able to take the fortress due to lack of artillery. Venice itself was in conflict with its Italian neighbors, which led Mehmed to begin another campaign against the Albanians. This would result in another siege on Krujë.

Background

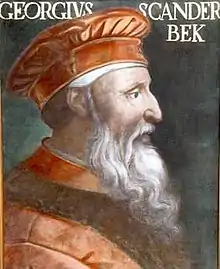

Skanderbeg had been an Ottoman sanjakbey, who defected from the empire and united several Albanian princes under the League of Lezhë. From Krujë, his main fort, he led the league in the Ottoman-Albanian wars. Having defeated the Ottomans in many battles he allied with Western Christian states and leaders, especially with Alfonso V of Aragon and the Papal States. On 14 August 1464, Pope Pius II, one of Skanderbeg's major benefactors, died and his plans for a crusade against the Ottoman Empire disintegrated.[1] The alliances and promises for help from the major Christian powers were canceled with the exception of the Kingdom of Hungary under Matthias Corvinus and the Republic of Venice.[2] Sultan Mehmed II realized the power vacuum created after Pius died and he tried to take advantage of the situation. He thus attempted to sign a peace agreement with Hungary and Venice so that his forces could focus on Albania to gain a base for future campaigns in the Italian peninsula. His efforts were unsuccessful, however, since neither Venice nor Hungary accepted his proposed treaty. Mehmed thus kept his armies stationed in the Balkans, one force near Jajce in Bosnia, one in Ohrid, and another one in the Morea.[2]

Skanderbeg led an incursion into Ottoman territory near Ohrid with the aid of Venetian forces under a condottiero named Antonio da Cosenza, also known as Cimarosto, on 6 September 1464. Together, they defeated the Ottoman forces under Şeremet bey stationed there on 14 or 15 September.[3][4] The Venetian Senate informed the Hungarians of the joint Albanian-Venetian success on 29 September. Mehmed, sensing the weakness in his frontier, assigned Ballaban Badera as commander, replacing Şeremet. Ballaban was an Albanian by birth who had been incorporated into the Ottoman army through the devşirme system and was sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Ohrid in 1464 and 1465. In the meantime, Pope Paul II began planning his own crusade, but with means different from his predecessor. He planned to get the major European states to help fund the crusade while Venice, Hungary, and Albania would do the fighting.[5] He also wanted to aid the Albanians as much as possible and urged the Kingdom of Naples to supply Skanderbeg with able forces. Venice began to consider peace with the Ottomans since its resources had significantly decreased, while Hungary adopted a defensive strategy, however, pressure from the Pope and Skanderbeg forced them to abort their efforts.[6]

The Ottoman-Albanian war continued through 1465 with Ballaban Badera meeting Skanderbeg at Vaikal, Meçad, Vaikal again, and Kashari. In the meantime, Mehmed continued to negotiate peace with Hungary and Venice. Skanderbeg found himself isolated during these negotiations, even if they did not succeed, as the conflicting powers temporarily ceased conflict. Furthermore, Ferdinand I of Naples did not send his promised forces and the Venetian forces under Cimarosto left Albania.[7][8] During the autumn of 1465, Ottoman forces moved from the Morea and Bosnia in order to speed up the peace negotiations. Venice, however, refused peace and Skanderbeg believed that a new Albanian-Venetian campaign would begin. He kept Pal Engjëlli, his ambassador, in constant correspondence with the Signoria (Venetian Senate), which sent him to Albania to inform Skanderbeg that troops were being raised, although only 300 had been recruited at the time, with Cimarosto as the commander.[7] Venice was also in the process of sending its provveditores in Albania Veneta 3,000 ducats to recruit men. They would also send four cannons, ten springalds, and ten barrels of gunpowder. Throughout April, rumors spread that the Ottomans were preparing to march into Albania. By 18 April 1466, Venice received knowledge that the Ottomans were heading towards Albania.[9]

Campaign

Once news of the Ottoman approach arrived, Venice sent reinforcements to its cities along Albania; Durazzo (Durrës) had already garrisoned 3,000 men. The Scutari Fortress was also reinforced after Skanderbeg's counsel and the walls were rebuilt. On 19 April 1466, news spread that the sultan was going to march into Avlonya (Vlorë) with an army of 100,000 men[10] although the Ragusans reported that the number was 30,000.[11] Ottoman forces were ready to enter the Kingdom of Naples and pressured Ferdinand to form an alliance with Mehmed.[12] The situation was not clear in the Balkans, however, as it was thought that the Ottomans could march against Bosnia, Serbia, Dalmatia, Negroponte, or Albania.[10] By the beginning of May, however, it was clear that the Ottomans would attack Albania because of the approach of Mehmed's troops towards Albania after the end of his campaigns in Wallachia, Karaman, and the Morea. None of the promised reinforcements from Naples and Venice arrived and Skanderbeg was thus left to fight Ottoman forces only with the league's troops.[10]

Ottoman activities in Albania

News arrived from eastern Albania that the Ottomans had initiated massacres in the area. The pope was distressed by this and called on the Christian princes of Europe to aid Skanderbeg.[10] Soon after, Mehmed's men marched into Albania. Unlike his father Murad II, Mehmed considered that the only way Albania could be conquered would be through isolating Krujë, the main Albanian fortress, by reducing Skanderbeg's manpower, supplies, and political and moral backing. Afterwards, Krujë would be put under siege. The Ottoman campaign was thus sent in two directions: one through the Shkumbin River valley and another through the Black Drin River valley. Both fielded men in the frontier regions, right and left of both valleys, and would engage in massacring the local populations, raiding inhabited areas, and burning every village which offered resistance. The populations thus decided to flee into safe areas.[13]

Skanderbeg did not expect such a campaign and his army was not ready to halt the advances. According to an act released Monopoli in Apulia, an army of 300,000 soldiers (a figure considered to be exaggerated) had marched into Albania, massacred 7,000 people, and sacked many populated areas, while Skanderbeg was preparing to flee to Italy.[13] However, Skanderbeg had remained in Albania but he had sent twelve ships with many inhabitants of Krujë to Italy as refugees. With them, he sent his wife, Donika, and his son, Gjon. They were headed to Monte Sant'Angelo, a castle awarded to Skanderbeg after his campaigns to restore Ferdinand's rule. The arrival of Albanian refugees further distressed the pope and many Italians who had come to believe that Albania had been conquered and that Mehmed was now preparing to march into Italy.[14][15] News to the contrary also reached Rome saying that the League of Lezhë had not been broken and that Krujë still stood.[16]

The League of Lezhë saw a massive struggle against Ottoman forces and its front was expanded throughout Albania.[16] Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains surrounding Scutari (Shkodër) where he collected men to relieve Krujë.[17] Mehmed's akıncı were allowed to raid the country, a decision which, according to scholar Mehmed Neshriu, was an act of reprisal regarding Skanderbeg's raids in Macedonia in 1464, which interrupted his siege on Jajce. Idris Bitlisi, however, says that Mehmed's campaign was a response to the breaking of the ceasefire in 1463 when Skanderbeg learned that the crusade against the Ottomans organized by Pius II was ready to set off from Ancona.[18] The resistance itself was described by Tursun Bey: the Albanians had gained control of the mountaintops and valleys where they had their kulle (fortified towers) which were dismantled when captured; those inside, especially the young men and women, were sold to slavery for 3,000–4,000 akçe each. Michael Critobulus, a Greek historian for the sultan, also describes the resistance and its aftermath. The Albanians in his chronicle had likewise gained the mountaintops;[19][20] the light Ottoman infantry climbed up the heights where they cornered the Albanians behind a cliff and fell on them. Many Albanians jumped from the cliffs to escape massacre.[19][20][21] The soldiers then spread throughout the mountains and captured many as slaves while also taking anything of value.[22][23] Furthermore, in order to secure future marches into Albania, Mehmed ordered forests through which the main roads ran through to be cut down. In this way, he created wide military roads which were secure.[24]

Siege

The first phase of the Ottoman campaign to isolate Krujë lasted for two months.[22] According to Marin Barleti, Skanderbeg's main biographer, Skanderbeg had placed 4,400 men under Tanush Thopia as defenders of the castle.[25] This force included 1,000 Venetian infantry under Baldassare Perducci[11] and 200 Neapolitan marksmen.[26] Skanderbeg removed his men from the fortress of Krujë in a manner similar to the first siege. Mehmed had marched into Albania with Ballaban Badera under his command.[27] He offered rewards to the garrison if they surrendered, but the garrison responded by bombarding the Ottoman positions.[28] The Ottomans then began to heavily bombard the fortress but this came to no effect.[15][27][29] According to documentary sources, the siege began in mid-June, one month after Mehmed began his campaign to force the eastern regions of Albania into submission. Mehmed's campaigns there had put Skanderbeg under massive strain while the latter had yet to receive financial aid from abroad.[30]

In the beginning of July, Skanderbeg sent Pal Engjëlli to Venice. On 7 July, Engjëlli informed the Venetians that the League of Lezhë continued and Krujë still stood, contrary to rumors that said otherwise. He thus requested the arrival of promised Venetian forces when they signed a treaty of alliance on 20 August 1463 and the promised contribution of 3,000 ducats.[30] The Venetians responded that they were already in a difficult situation due to the Ottoman threat in Dalmatia and the Aegean where they possessed territories. They also responded that they had had difficulty recruiting new soldiers due to financial trouble and could only send 1,000 ducats to its provveditores in Albania. Despite these difficulties, Skanderbeg and his men continued fighting.[30] After becoming convinced that Krujë would not be taken, Mehmed left 18,000 cavalry and 5,000 infantry under Ballaban and in June 1466 withdrew with his main army.[31][32] He withdrew from the siege to Durazzo where he pillaged the area in rage.[11][31] When Mehmed withdrew from Albania, he deposed Dorotheos, the Archbishop of Ohrid, and expatriated him together with his clerks and boyars and a considerable number of citizens of Ohrid to Istanbul, probably because of their anti-Ottoman activities during Skanderbeg's campaigns since many of them supported Skanderbeg and his fight.[33][34][35] He took with him 3,000 Albanian prisoners.[36]

Construction of Elbasan Fortress

Despite his inability to subdue Krujë, Mehmed decided that the Ottoman presence would not depart from Albania. He organized a timar in eastern Albania to weaken Skanderbeg's domains. The new Ottoman possessions were collected and placed under the administration of the Sanjak of Dibra. He also decided to build a powerful fortress in central Albania to counterbalance Krujë's position and to form a base for further Ottoman campaigns.[30] The fortress would be called Ilbasan (Elbasan). According to Ottoman chronicler Kemal Pashazade, the sultan would place several hundred men to patrol the area and defend the fortress. The foundations were built upon a field called Jundi, located in a Shkumbin valley, where the geographic conditions were regarded as favorable. Since the resources had been gathered and stored beforehand, Elbasan was built within a short time (one month[37]) and Franz Babinger believes the work to have begun in July.[38] Critobulus, who accompanied Mehmed in this campaign, describes that the men stationed in Elbasan would constantly harass the Albanians, to leave them no place for refuge, and to repel any Albanian force which descended from the mountains. Due to his personal guidance, Mehmed was able to see the construction finish before the summer ended. There would also be inhabitants inside to serve the 400 soldiers stationed there along with cannons and catapults; the fortress would be under the command of Ballaban Badera.[39][40]

The personal care and attention Mehmed paid to Elbasan's construction testifies its importance in the sultan's plans. This is further testified by the message Mehmed gave to his son, the future Bayezid II, describing how he had devastated the country and at its center built a powerful fortress. Upon his exit from Albania, Marin Barleti says that Mehmed passed through Dibra and massacred 8,000 people, a figure close to the number given by the Ottoman chronicler Oruc ben Adil of 7,500.[41] The importance of the fortress was further underscored by its position on the ancient Via Egnatia and its central position in the Shkumbin valley from where the Ottomans could travel to the coast. Elbasan concerned not only the Albanians, but also the Venetians, who considered its proximity to Durazzo (30 miles (48 km)) alarmant.[41][42] On 16 August, around the time that the building of Elbasan was completed, Venice urged its proveditors in Albania to cooperate with the Italian and native forces in their proposed siege on Elbasan. Venetian faith in Skanderbeg began to subside, however, since the sultan took a much more aggressive approach in his relations with Venice. Since the Signoria still had not delivered its promised aid, Skanderbeg sent his son John to Venice.[43][44] Even though the war was at its apogee, John returned from Venice empty-handed. This forced Skanderbeg to look towards Rome and Naples for aid.[45]

Skanderbeg in Rome

During October 1466, Skanderbeg travelled to Italy to reach an agreement with Ferdinand of Naples and Pope Paul II over the provisions, which they would be willing to provide. As a result of the inter-Italian rivalries, the possibility of a crusade was abandoned. Since Paul was Venetian, Ferdinand was also worried that his interests could be inhibited by the pope and eventually he didn't send any resources to Skanderbeg until disagreements with his neighbors were resolved.[46] Thus, Skanderbeg departed from Naples without any definitive agreement on the aid that would be provided by Napes. Venice offered the same and Skanderbeg went to Paul after the latter had declared that the Christian League had raised 100,000 ducats for the planned crusade. Skanderbeg reached Rome on 12 December 1466 where he was greeted by the cardinals and their families. Here they received the impression of Skanderbeg as a poor old man,[47][48] dressed as an ordinary soldier.[37][49] He was offered residence in Palazzo di San Marco, in what is now called Piazza Venezia but refused it and instead wanted to stay with another Albanian whose house later took the name Palazzo Scanderbeg. He was greeted by Italian ambassadors from the various states who offered "aid and favors"[50] and by several bishops and prelates.[51] Paul, however, was still wary of giving Skanderbeg aid because he reasoned that the Neapolitan threat was more powerful than the Ottoman one. Unlike his predecessors, Paul never attempted to form a crusade against the Ottomans and instead preferred the use of pacification methods. Nevertheless, Skanderbeg continued to stay in Rome, hoping that Paul would allocate part of his funds (of about 500,000 ducats) to Albania.[52] Paul asserted to Skanderbeg that Venice's refusal to cooperate with him prevented him from directly helping Skanderbeg. Thus, Skanderbeg was sent to the Signoria to negotiate their stance.[53][54]

During the last weeks of the year in Albania, there was no fighting since the Ottomans did not normally engage in battle during the winter. But Krujë was still under siege and Ottoman garrisons in other areas remained. Life became harder for the population after the destruction of crops and villages and the masses of refugees.[53] By 22 November, news came to Venice about the campaigns of Sinan bey against Albania Veneta[55] in order to pressure the Republic to accept a peace or a ceasefire. The Signoria was slow to come to terms with Mehmed due to the pressure put on it by Pope Paul, Hungary, and Naples to remain at war. The attempt to sway the Venetians failed and the campaign was cancelled. This had an adverse effect for the Ottomans since Lekë Dukagjini, Skanderbeg's ally in northern Albania, decided to work without reservation with Skanderbeg against the Ottomans.[53] In Rome, the pope continued to hold Skanderbeg and would only give him 300 ducats to support his stay.[54] On Christmas Eve, Paul invited Skanderbeg to a ceremony where he was awarded with a sword and helmet[56] and referred to him as Alexander, king of the Epirotes. By 7 January 1467, a consistory convened where Skanderbeg and the pope were present. According to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, the pope's appeal to fund Skanderbeg with only 5,000 ducats was heard and when the Cardinals responded that the fund was minimal, Paul explained that he would send more once Italy was pacified.[54] Paul's decision led to a fierce debate on Italy's future which left Albania's fate undiscussed.[56][57] A second consistory was called on 12 January but did not result in anything favorable for Skanderbeg. Contemporaries were critical of the pope's delays but he explained that he was waiting to see what Ferdinand of Naples was willing to offer before offering anything himself, in order not to waste funds.[58]

Skanderbeg's view of the situation worsened with news coming from Albania, which strengthened his opinion that his time in Italy was becoming more and more irrational. His pessimism grew once he found out that Venice was now pressuring Paul into refusing Skanderbeg aid since they wished to put an end to the war and capitulate Krujë. During the first days of February, news arrived from the Republic of Ragusa that the campaign was nearing its end and that if the necessary actions were not brought up to speed, Albania would fall along with Venice's possessions.[58] Skanderbeg's requests for proper aid were continually rejected on the basis that Italy's peace must first be secured and instead Paul ordered Ferdinand to award to Skanderbeg what tribute would have been given to Rome. Skanderbeg lost all hope and decided to return to Albania before pleas from several cardinals convinced to stay, offering aid from their own pockets and hope in persuading Paul. A third consistory was convened on 13 February 1467 which, like the other two, came to nothing regarding aid to Skanderbeg. Skanderbeg thus began his departure from Rome. Paul met with Skanderbeg and gave him the authority to pull 7,500 ducats from Ferdinand's aforementioned tribute to Rome.[59][60] This amount had not been gathered, however, and Paul thus offered Skanderbeg 2,300 ducats. Skanderbeg departed from Rome on 14 February and soon received news from Albania: the war was nearing its end and needed Skanderbeg to return; an Ottoman force sent to defeat the League of Lezhë definitively, however, had been defeated.[61] He met with Giosafat Barbaro in Scutari, the Venetian provveditore in Albania Veneta, where he gathered help from Venetian nobles.[62][63][64]

Final battles

The defeat of the Ottoman forces showed that the League of Lezhë had yet to be fully defeated.[61] This allowed Skanderbeg to visit Ferdinand before his departure from Italy, but he received only 1,000 ducats, 300 carts of grain, and 500 ducats to support Krujë's munitions. While Skanderbeg was in his court, Ferdinand received an ambassador from Mehmed offering peace, signaling that the Ottomans did not have any aggressive intentions towards Naples. Ferdinand accepted the proposal and Skanderbeg thus began his return to Albania.[65] Ballaban continued to strengthen the siege against Krujë. Upon returning to Albania, the political situation began to change. The once distant Albanian nobles, among them Dukagjini, were now convinced of their impending defeat and allied themselves with Skanderbeg. Meanwhile, the Venetians ended their attempts to negotiate peace with Mehmed and accepted cooperation with Skanderbeg. Skanderbeg met with Dukagjini and other northern Albanian nobles in Alessio (Lezhë) where they gathered an army to assault Ballaban's forces.[66] Together with 400 of Dukagjini's cavalry and a large number of infantry, 600 heavily armed Italian soldiers, and 4,000 locals from Durazzo, Scutari, Alessio, Drivast (Drisht), and Antivari (Bar), Skanderbeg commanded 13,400 men to relieve Krujë as reported by Demetrio Franco, one of Skanderbeg's primary biographers and personal associates,[67] who also served in Skanderbeg's ranks. Among those who joined Skanderbeg was Nicolo Moneta, a lord of Scutari and wealthy Venetian patrician.[64]

Ballaban's camp was located on the hills southwest of Krujë and at the bottom of the mountain nowadays known as Mt. Sarisalltëk, he placed a guarding force. The rest of his army surrounded Krujë.[29] Skanderbeg and his allies marched through the mouth of the Mat River and cut through the woods of Jonima to the boundaries of Krujë.[68] Skanderbeg's commanders were assigned different groups for an assault on the main Ottoman camp: northern Albanian forces would be put under Dukagjini's command, Venetian battalions were under the command of Moneta, and Skanderbeg's most trusted forces would be assigned to another group under his command; Krujë's garrison would continue to defend the fortress. Moneta's and Dukagjini's men would attack the besieging forces from the north and Skanderbeg's men would attack from south of Krujë while also blocking any possible Ottoman reinforcements from the east.[69] Skanderbeg first assaulted the guarding force which Ballaban had left and he gained control of this strategic point.[29] Skanderbeg then managed to defeat the Ottoman relief forces under Ballaban's brother, Jonuz, and captured him and his son.[29][70] Four days later, an organized attack from Skanderbeg and the forces from Krujë was carried during which Ballaban forces retreated and he himself was killed in the resulting clashes by Gjergj Lleshi (Georgius Alexius).[69][71]

With the death of Ballaban, Ottoman forces were left surrounded and according to Bernandino de Geraldinis, a Neapolitan functionary, 10,000 men remained in the besieging camp. Those inside the encirclement asked to leave freely to Ottoman territory, offering to surrender all that was within the camp to the Albanians. Skanderbeg was prepared to accept, but many nobles refused.[72] Among them was Dukagjini, who wanted to attack and destroy the Turkish camp. Demetrio Franco described Dukagjini's proposal with the Albanian word Embetha which in modern Albanian means Mbë ta or in English Upon them.[73][74][75] The Albanians thus began to annihilate the surrounded army before the Ottomans cut a narrow path through their opponents and fled through Dibra.[76] On 23 April 1467, Skanderbeg entered Krujë.[72] Meanwhile, the Venetians had taken advantage of Mehmed's absence in Albania and sent a fleet under Vettore Capello into the Aegean. Capello attacked and occupied the islands of Imbros and Lemnos after which he sailed back and laid siege to Patras. Ömer Bey, the Ottoman commander in Greece, led a relief force to Patras where he was initially repelled before turning on his pursuers, forcing them to flee, terminating their campaign.[77]

The victory was well received among the Albanians, and Skanderbeg's recruits increased as documented by Geraldini: Skanderbeg was in his camp with 16,000 men and every day his camp grows with young warriors.[73] The victory was also well received in Italy with contemporaries hoping for more such news. But, despite the Ottoman loss, the victory did not signal an end to the war.[73] Skanderbeg's damaged forces, however, had been renewed with northern warriors and Venetian battalions. The situation remained critical, however, due to the economic hardships suffered during the siege. Skanderbeg's only expectancy was for help to come from Italy, but the Italian states, despite sending congratulatory messages, sent no financial aid. Hungary continued its defensive war and thus Skanderbeg's only remaining ally was Venice. Even Venice became skeptical of continuing the war and was alone in allying with Skanderbeg.[73] Venice reported to Hungary that Mehmed had offered peace and was willing to accept it. Hungary also opted for peace, but Mehmed only sought peace with Venice in order to isolate Skanderbeg and thus peace was not signed. Skanderbeg and Venice continually began to worry about the Ottoman garrison in Elbasan. Skanderbeg led some assaults on the fortress after being urged to by Venice but failed to capture it due to lack of artillery.[78] According to Critobulos, Mehmed was troubled after learning of the Ottoman defeat and began preparations for a new campaign.[79][80] Venice itself was in conflict with its Italian neighbors who had grown wary of its increasing influence in the Balkans. With the western powers fighting among themselves, the road to Albania was open.[81] Mehmed thus decided to send a force to subdue Albania conclusively which resulted in a new siege on Krujë.[80]

Notes

- Schmitt 2009, p. 363

- Frashëri 2002, p. 417

- Frashëri 2002, p. 418

- Schmitt 2009, p. 359

- Frashëri 2002, p. 419

- Frashëri 2002, p. 420

- Frashëri 2002, p. 421

- Schmitt 2009, p. 361

- Frashëri 2002, p. 422

- Frashëri 2002, p. 423

- Babinger 1978, p. 252

- Schmitt 2009, p. 365

- Frashëri 2002, p. 424

- Frashëri 2002, p. 425

- Freely 2009, p. 110

- Frashëri 2002, p. 426

- Schmitt 2009, p. 374

- Frashëri 2002, p. 427

- Frashëri 2002, p. 428

- Freely 2009, p. 109

- Hodgkinson 1999, pp. 209–210

- Frashëri 2002, p. 429

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 210

- Schmitt 2009, p. 380

- Noli 1947, p. 330

- Schmitt 2009, p. 372

- Frashëri 2002, p. 430

- Franco 1539, p. 343

- Karaiskaj 1981

- Frashëri 2002, p. 431

- Setton 1978, p. 279

- Franco 1539, pp. 343–344

- Shukarova 2008, p. 133

- Srpsko arheološko društvo 1951, p. 181

- Institut za balkanistika 1984, p. 71

- Babinger 1978, p. 253

- Noli 1947, p. 331

- Frashëri 2002, p. 433

- Frashëri 2002, pp. 433–434

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 212

- Frashëri 2002, p. 437

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 211

- Frashëri 2002, p. 438

- Schmitt 2009, p. 391

- Frashëri 2002, pp. 438–439

- Frashëri 2002, p. 440

- Frashëri 2002, p. 441

- Schmitt 2009, p. 393

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 215

- Frashëri 2002, p. 442

- Noli 1947, p. 332

- Frashëri 2002, p. 445

- Frashëri 2002, p. 446

- Freely 2009, p. 111

- Schmitt 2009, p. 382

- Schmitt 2009, p. 395

- Frashëri 2002, p. 447

- Frashëri 2002, p. 448

- Frashëri 2002, p. 449

- Schmitt 2009, p. 396

- Frashëri 2002, p. 450

- Franco 1539, p. 344

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 216

- Schmitt 2009, p. 399

- Frashëri 2002, p. 451

- Frashëri 2002, p. 453

- Franco 1539, pp. 344–345

- Schmitt 2009, p. 400

- Frashëri 2002, p. 454

- Noli 1947, p. 333

- Franco 1539, p. 345

- Frashëri 2002, p. 455

- Frashëri 2002, p. 456

- Franco 1539, p. 346

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 217

- Noli 1947, p. 334

- Freely 2009, p. 112

- Frashëri 2002, p. 457

- Noli 1947, p. 335

- Schmitt 2009, p. 402

- Schmitt 2009, p. 401

References

- Babinger, Franz (1978). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Bollingen Series 96. Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim. Edited, with a preface, by William C. Hickman. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 164968842.

- Franco, Demetrio (1539), Comentario de le cose de' Turchi, et del S. Georgio Scanderbeg, principe d' Epyr, Venice: Altobello Salkato, ISBN 99943-1-042-9

- Frashëri, Kristo (2002), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468 (in Albanian), Tiranë: Botimet Toena, ISBN 99927-1-627-4

- Freely, John (2009), The grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II, conqueror of Constantinople and master of an empire, New York: The Overlook Press, ISBN 978-1-59020-248-7

- Hodgkinson, Harry (1999), Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, London: Centre for Albanian Studies, ISBN 978-1-873928-13-4

- Institut za balkanistika (1984), Balkan studies, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

- Karaiskaj, Gjerak (1981), "Rrethimi i dytë dhe i tretë i Krujës (1466–1467)", Pesë mijë vjet fortifikime në Shqipëri, Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nëntori"

- Noli, Fan Stilian (1947), George Castroiti Scanderbeg (1405–1468), International Universities Press, OCLC 732882

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2009), Skënderbeu, Tiranë: K&B, ISBN 978-3-7917-2229-0

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1978). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

- Shukarova, Aneta (2008), Todor Chepreganov (ed.), History of the Macedonian People, Skopje: Institute of National History, ISBN 978-9989-159-24-4, OCLC 276645834

- Srpsko arheološko društvo (1951), Starinar (in Serbian), Belgrade: Arheološki institut, OCLC 1586392