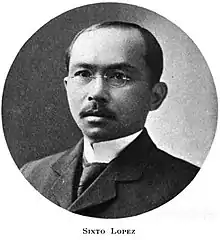

Sixto López

Sixto Castelo López (April 6, 1863 - March 3, 1947) was secretary of the Philippine mission sent to the United States in 1898 to negotiate US recognition of Philippine independence.

Early life

Sixto López was born on April 6, 1863, the eldest son of Natalio López by his second wife, Maria Castelo. The Lópezes were an illustrious family who owned vast tracts of sugarcane fields in the province of Batangas.

A schoolmate of the writer and patriot Jose Rizal, he soon extended loans so that the latter could circulate his works in the Philippines. As a result, López was hunted down as "Rizal's most active agent", escaping Rizal's fate only by accepting voluntary exile to London upon his capture by General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. during the Philippine–American War.

Further activities

In London, López undertook a risky operation to rescue Rizal from the hands of his executioners. His group attempted to intercept him on his way from Barcelona to Manila in vain.

After Rizal's execution in 1898, López was appointed secretary to the diplomatic commission formed by the newborn Philippine Republic under the leadership of Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo. The Commission’s main task was to go to Washington to seek for the recognition of the newly formed nation's independence.

During their United States mission, López wrote numerous dispatches to Aguinaldo and to the Central Committee at Hong-Kong urging a cessation of hostilities, pointing out that armed resistance could not secure independence, but would only confuse the issues and do injury to a good cause.

When the spate of hostilities between the Philippines and America erupted, the delegation left the US, but López soon returned to Boston, Massachusetts in 1900 to be a guest of Fiske Warren, an officer of the New England Anti-Imperialist League. While there, he repeatedly urged sending one or more Filipinos to America with the object of informing the American people of the real situation in the country being woefully misrepresented by Gen. Elwell Otis and his associates. He then made extensive speaking tours and secured publication of numerous articles in the American press advocating independence. In one of those articles published in the "Independent" of December 14, 1899 and addressed to the American people, he concludes as follows:

"Why not negotiate? If negotiations fail, it will then be time enough for war. True, in the past, our overtures of peace and good will were not received in a hearty manner by the Administration. But let that pass. It cannot be undignified to do what honor and righteousness demand. Who will help me in the cause of peace? Could any cause be worthier the genius of the statesmen of a great nation?

"In placing this statement before the people of America, I beg to assure them that whatever its demerits may be, it is the outcome of a sincere desire for peace and for an honorable settlement of the differences and difficulties of the Philippine question."

His moderate demeanor enabled him to establish close ties with Americans in Massachusetts, that soon he became an influential voice in the Anti-Imperialist League's shift from a nearly exclusive focus on the effects of imperialism on the United States to one, which included a component of solidarity with the Filipino people. López remained in exile for many years because he refused to take the pledge of allegiance to the United States that was required for his entrance back into his homeland.[1]

His sister, Clemencia López, arrived in the U.S. in 1902 to secure the services of the famed jurist and future Supreme Court justice, Louis Brandeis in order to aid her brother's fight against deportation to Guam. She told reporters that her brother and many others who had surrendered in good faith, had been arbitrarily deported by MacArthur.

Reminding his colleagues that arbitrary deportation of this sort had been a key grievance of the American colonists against the British King, George II, Senator Hoar took up Miss López's cause on the U.S. Senate floor.

Writing Online

- Lopez, Sixto. "Do the Filipinos Desire American Rule?" Gunton's Magazine (Jun. 1902). Accessed from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York).

- Sixto López and Thomas T. Patterson (1904), "Too Wise To Work." In the Springfield Republican; reprinted in Liberty XIV.21 (June, 1904). 6.

- Eyot, Canning. The Story of the Lopez Family: A Page from the History of the War in the Philippines. Boston, Massachusetts: James H. West Company, 1904). See also a description of this book from the Commonwealth Cafe.