Batangas

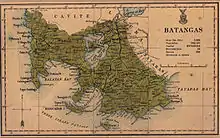

Batangas (Tagalog: Lalawigan ng Batangas IPA: [bɐˈtaŋgɐs]) is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Its capital is the city of Batangas, and is bordered by the provinces of Cavite and Laguna to the north, and Quezon to the east. Across the Verde Island Passages to the south is the island of Mindoro and to the west lies the South China Sea. Poetically, Batangas is often referred to by its ancient name Kumintáng.

Batangas | |

|---|---|

| Province of Batangas | |

_(J.P._Laurel_Highway%252C_Batangas_City)(2018-07-30).jpg.webp)      From left-to-right, top-to-bottom: Batangas Provincial Capitol; Anilao; Taal Volcano; Taal Basilica; Agoncillo–Mariño House; Malabrigo Point Lighthouse | |

Seal | |

Nicknames:

| |

| Motto(s): "Rich Batangas!" | |

| Anthem: Himno ng Batangan (Batangas Hymn) | |

Location in the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 13°50′N 121°00′E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Calabarzon (Region IV-A) |

| Founded | December 8, 1581 |

| Capital | Batangas City |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlalawigan |

| • Governor | Hermilando I. Mandanas (PDP–Laban) |

| • Vice Governor | Jose Antonio S. Leviste II (PDP–Laban) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,119.75 km2 (1,204.54 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 44th out of 81 |

| Highest elevation | 1,077 m (3,533 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,694,335 |

| • Rank | 7th out of 81 |

| • Density | 860/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 6th out of 81 |

| Divisions | |

| • Independent cities | 0 |

| • Component cities | |

| • Municipalities | |

| • Barangays | 1,078 |

| • Districts | 1st to 6th districts of Batangas |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PHT) |

| ZIP code | 4200–4234 |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)43 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH-BTG |

| Spoken languages |

|

| Website | www |

Batangas is one of the most popular tourist destinations near Metro Manila. It is home to the well-known Taal Volcano, one of the Decade Volcanoes, and Taal Heritage town, a small town that has ancestral houses and structures dating back to the 19th century. The province also has numerous beaches and diving spots including Anilao in Mabini, Sombrero Island in Tingloy, Ligpo Island and Sampaguita Beach in Bauan, Matabungkay in Lian, Punta Fuego in Nasugbu, Calatagan and Laiya in San Juan. All of the marine waters of the province are part of the Verde Island Passage, the center of the center of world's marine biodiversity.

Batangas City has the second largest international seaport in the Philippines after Metro Manila. The identification of the city as an industrial growth center in the region and being the focal point of the Calabarzon program is seen in the increasing number of business establishments in the city's Central Business District (CBD) as well as numerous industries operating in the province's industrial parks.

Etymology

The first recorded name of the province was Kumintáng, whose political center was the present-day municipality (town) of Taal, prior moving to municipality of Balayan. Balayan was considered the most progressive town of the region. An eruption of Taal Volcano destroyed a significant portion of the town, causing residents to transfer to Bonbon (now Taal), the name eventually encompassing the bounds of the modern province.

The modern name of "Batangas" is derived from Spanish batangas, meaning "outrigger [booms]".[3] It is derived Tagalog batangan which refers to a type of tough mangrove wood used in building the large rounded beams (also called batangan) across the traditional outriggers (katig) of Filipino bangka boats.[4][5]

History

Archaic epoch

Long before the arrival of the Spaniards in the Philippines, large centers of population already thrived in Batangas. Native settlements lined the Pansipit River, a major waterway. The province had been trading with the Chinese since Yuan Dynasty until the first phase of Ming Dynasty in the 13th and 15th century. Inhabitants of the province were also trading with Japan and India. The Philippines ancestors were Buddhists and Hindus, but far from India and intermixed with animistic beliefs.

Archaeological findings show that before the settlement of the Spaniards in the country, the Tagalogs, especially the Batangueños, had attained a semblance of high civilization. This was shown by certain jewelry, made from a chambered nautilus' shell, where tiny holes were created by a drill-like tool. The Ancient Batangueños were influenced by India as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan. According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga[6] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[7]

One of the major archaeological finds was in January 1941, where two crude stone figures were found in Palapat in the municipality of Calatagan. They were later donated to the National Museum. One of them was destroyed during World War II.

Eighteen years later, a grave was excavated in nearby Punta Buaya. Pieces of brain coral were carved behind the heads of the 12 remains that were found. The site was named Likha (meaning "Create"). The remains were accompanied by furniture that could be traced as early as the 14th century. Potteries, as well as bracelets, stoneware, and metal objects were also found in the area, suggesting that the people who lived there had extensive contact with people from as far as China.

The presence of dining utensils such as plates or "chalices" found with the remains also suggest that prehistoric Batangueños believed in the idea of life-after-death. Thus, the Batangueños, like their neighbors in other parts of Asia, have similar customs of burying furniture with the dead.

Like the nearby tribes, the Batangan or the early Batangueños were a non-aggressive people. Partly because most of the tribes in their immediate environment were related to them by blood. Some weapons Batangans used included the bakyang (bows and arrows), the bangkaw (spears), and the suwan (bolo).

Being highly superstitious, the use of agimat (amulet or talisman) showed that these people believed in the presence of higher beings and other things unseen. The natives believed that forces of nature were a manifestation these higher beings.

The term 'Tagalog' may have been derived from the word taga-ilog or "river dwellers" referring to the Pasig River located further up north of the region. However, Wang Teh-Ming in his writings on Sino-Filipino relations points out that Batangas was the real center of the Tagalog tribe, which he then identified as Ma-yi or Ma-i. According to the Chinese Imperial Annals, Ma-yi had its center in the province and extends to as far as Cavite, Laguna, Rizal, Quezon, Bataan, Bulacan, Mindoro, Marinduque, Nueva Ecija, some parts of Zambales, and Tarlac. However, many historians interchangeably use the term Tagalog and Batangueño.

Henry Otley Beyer, an American archaeologist, also showed in his studies that the early Batangueños had a special affinity with the precious stone known as the jade. He named the Late Paleolithic Period of the Philippines as the Batangas Period in recognition of the multitude of jade found in the excavated caves in the province. Beyer identified that the jade-cult reached the province as early as 800 B.C. and lasted until 200 B.C.

Spanish colonization

In 1570, Spanish generals Martin de Goiti and Juan de Salcedo explored the coast of Batangas on their way to Manila and came upon a Malay settlement at the mouth of Pansipit River. In 1572, the town of Taal was founded and its convent and stone church were constructed later.

Officially, the Province of Bonbon was founded by Spain in 1578, through Fr. Estaban Ortiz and Fr. Juan de Porras. It was named after the name that was given to it by the Muslim natives who inhabited the area.

In 1581, the Spanish government abolished Bonbon Province and created a new province which came to be known as Balayan Province. The new province was composed of the present provinces of Batangas, Mindoro, Marinduque, southeast Laguna, and Camarines. After the devastating eruption of Taal Volcano in 1754, the old town of Taal, present day San Nicolas, was buried. The capital was eventually transferred to Batangas (now a city) for fear of further eruptions where it has remained to date.

In the same years that de Goiti and Salcedo visited the province, the Franciscan missionaries came to Taal, which later became the first Spanish settlement in Batangas and one of the earliest in the Philippines. In 1572, the Augustinians founded Taal in the place of Wawa, now San Nicolas, and from there began preaching in Balayan and in all the big settlements around the lake of Bombon (Taal). The Augustinians, who were the first missionaries in the diocese, remained until the revolution against Spain. Among the first missionaries were eminent men which included Alfonso de Albuquerque, Diego Espinas, Juan de Montojo, and others.

During the first ten years, the whole region around the Lake of Bombon was completely Christianized. It was done through the preaching of men who had learned the first rudiments of the language of the people. At the same time, they started writing manuals of devotion in Tagalog, such as novenas, and had written the first Tagalog grammar that served other missionaries who came.

Foundation of important parishes followed throughout the years: 1572, the Taal Parish was founded by the Augustinians; 1581, the Batangas Parish under Fray Diego Mexica; 1596, Bauan Parish administered by the Augustinian missionaries; 1605, Lipa Parish under the Augustinian administration; 1774, Balayan Parish was founded; 1852, Nasugbu Parish; and 1868, Lemery Parish.

The town of Nasugbu became an important centre of trade during the Spanish occupation of the country. It was the site of the first recorded battle between two European Forces in Asia in Fortune Island, Nasugbu, Batangas. In the late part of the 20th century, the inhabitants of Fortune Island discovered a sunken galleon that contained materials sold in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade.

Batangas was also among the first of the eight Philippine provinces to revolt against Spain and one of the provinces placed under Martial Law by Spanish Governor-General Ramon Blanco on August 30, 1896. This event was given distinction when Marcela Agoncillo, also a native of the province, made the Philippine Flag, which bears a sun with eight rays to represent these eight provinces.

American period

When the Americans forbade the Philippine flag from being flown anywhere in the country, Batangas was one of the places where the revolutionaries chose to propagate their propaganda. Many, especially the revolutionary artists, chose Batangas as the place to perform their plays. In an incident recorded by Amelia Bonifacio in her diary, the performance of Tanikalang Ginto in the province led not only to the arrest of the company but all of the audience. Later, the play was banned from being shown anywhere in the country.

General Miguel Malvar is recognized as the last Filipino general to surrender to the United States in the Philippine–American War.

Japanese occupation

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese sent their planes to attack the Philippines, launching major air raids throughout the country. The bombings resulted in the destruction of the Batangas Airport located in Batangas City, of which nothing remains today.[8] Batangas was also a scene of heavy fighting between the Philippine Army Air Corps and the Japanese A6M Zero Fighter Planes. The most notable air combat battle took place at height of 3,700 metres (12,000 ft) on December 12, 1941 when 6 Filipino fighters led by Capt. Jesús Villamor engaged the numerically superior enemy of 54 Japanese bombers and fighter escorts which raided the Batangas Airfield. Capt. Jesús Villamor won the battle, suffering only one casualty, Lt. César Basa who was able to bail out on a parachute as his plane was shot down only to be strafed by machine-gun fire from the A6M Zeroes.[9]

When Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered the overall retreat of the American-Filipino Forces to Bataan in 1942, the province was ultimately abandoned and later came under direct Japanese occupation. During this time, the Imperial Japanese Army committed many crimes against civilians including the massacre of 328 people in Bauan, 320 in Taal, 300 in Cuenca, 107 in San Jose, and 39 in Lucero.[10]

Liberation

| Battle of Batangas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

362,000 Filipino troops 30,000 Batangueño guerrillas 65,000 American troops | 156,000 Japanese troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Filipino troops 4,500 killed 14,000 wounded Batangueño guerrillas 700 killed 2,140 wounded American troops 2,000 killed 10,200 wounded |

Japanese troops 40,000 killed 12,000 wounded 3,000 captured | ||||||

As part of the Philippines Campaign (1944–45), the province's liberation began on January 31, 1945, when elements of the 11th Airborne Division under the U.S. Eighth Army went ashore on the beaches of Nasugbu, Batangas.[11] However, Batangas was not the main objective of the invasion force. Instead, most of its units headed north to capture Manila and by March 3, the capital was completely secured.

Liberation of Batangas proper by American forces began in March 1945 under the 11th Airborne Division and the 158th Regimental Combat Team (or 158th RCT).[12] The 158th Regimental Combat Team stationed in Nasugbu was tasked to secure the shores and nearby towns of Balayan and Batangas. The 11th Airborne Division from the Tagaytay Ridge would attack the Japanese defenses north of Taal Lake and open the Lipa corridor. By March 11 the 158th RCT had reached Batangas City.[12] In order to secure the two bays, 158th RCT needed to capture the entire Calumpang Peninsula near the town of Mabini, which was still held by some elements of the Japanese 2nd Surface Raiding Base Force. Fighting continued until March 16 when the whole peninsula was finally captured.[12]

Afterwards, the 158th RCT turned northward to meet the Japanese Fuji Force defenses at Mt. Maculot in Cuenca on March 19. The 158th RCT disengaged the Japanese on March 23 and were relieved by the 11th Airborne's 187th Glider Infantry Regiment. Another 11th Airborne Division task force, the 188th Infantry was ordered to dispatch troops around Batangas City and its remaining frontiers.[12] Meanwhile, the 11th Airborne Division's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment had begun the opening of the Lipa corridor at Santo Tomas and Tanauan before being relieved by the 1st Cavalry Division and moving via Tagaytay to Bauan and San Jose.[12]

The last major offensive for the capture of the Lipa Corridor began when 188th Infantry Task Force from Batangas City left for Lipa on March 24.[12] The same that day, the 187th Infantry Task Force launched an attack against the remaining Japanese positions in Mt. Maculot. Heavy fighting continued until April 17. The final capture of Mt. Maculot came by April 21.[12]

The 188th Infantry Task Force met stiff resistance from Fuji Force's 86th Airfield Battalion on March 26. To the north, the 1st Cavalry Division attacked the remaining Japanese defenses in the towns of Santo Tomas and Tanauan and succeeded in linking up with the advancing 187th and 188th task forces from the south.[12] Lipa was captured by the 1st Cavalry Division on March 29. The final defeat of the Fuji Force came at Mt. Malepunyo at the hands of the 511th on May 2.[13]

With the capture of Lipa and Mt. Malepunyo, organized resistance ended in the province. Some elements of the 188th Infantry Task Force were left to clear the Batangas mountains located southeast of province from the remaining Japanese.[12]

Throughout the battle, recognized Filipino guerrilla fighters played an important key role in the advancement of the combined American and Philippine Commonwealth troops, providing key roads and information for the Japanese location of defenses and movements. The 11th Airborne Division and attached Filipino guerillas had 390 casualties of which 90 were killed. The Japanese however lost 1,490 men.[12] By the end of April 1945, Batangas was liberated and fully secured for Allied control, thus ending all hostilities.

The movements of the military general headquarters and military camp bases of the Philippine Commonwealth Army happened from January 3, 1942 to June 30, 1946 and included the province of Batangas in southern Luzon. During the engagements of the Anti-Japanese Imperial Military Operations in Manila, southern Luzon, Mindoro and Palawan from 1942 to 1945, (including the provinces of Rizal, Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Mindoro, and Palawan), units of the Philippine Constabulary, with the local guerrilla resistance joined with the U.S. liberation military forces against the Japanese Imperial armed forces.

Under the Southern Luzon Campaign, local Filipino soldiers of the 4th, 42nd, 43rd, 45th, and 46th Infantry Division of the Philippine Commonwealth Army and 4th Constabulary Regiment of the Philippine Constabulary joined the battle for the liberation of Batangas.

Post-war period

After Douglas MacArthur made his famous landing in the Island of Leyte, he came next to the town of Nasugbu to mark the liberation of Luzon. This historic landing is remembered by the people of Batangas every last day of January, a holiday for the Nasugbugueños.

After the United States of America relinquished control of the Philippines, statesmen from Batangas featured prominently in the government. These include the legislators Felipe Agoncillo, Galicano Apacible (who later became the Secretary of Agriculture), Ramon Diokno, Apolinario R. Apacible, Expedito Leviste, Gregorio Katigbak, Teodoro Kalaw, Claro M. Recto, and José Laurel, Jr.

It is also notable that when President Manuel L. Quezon left the Philippines during the Japanese Occupation, the Japanese government in the Philippines chose the Batangueño José Laurel, Sr. as the de jure President of the Puppet Republic.

Under the Marcos Dictatorship

Batangueños were not spared the social and economic turmoil that began during the second term of President Ferdinand Marcos, including his 1971 suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, his 1972 declaration of martial law, and his continued hold on power from the lifting of martial law in 1981 until his ouster under the People Power Revolution of 1986.

Prominent Batangueño senator Jose W. Diokno was one of the first people Marcos imprisoned without charges,[14] because according to then-Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, the regime found it necessary to "emasculate the voices of the opposition."[15]

In 1981, Marcos used his Presidential “power of eminent domain” to convert 167 hectares of agricultural lands in San Rafael, Calaca, for industrial use, paving the way for the construction of the Semirara Calaca power plant regardless of its health and environmental impact.[16]

Among the later victims of the regime were student leaders Ismael Umali, Noel Clarete, and Aurelio Magpantay from Western Philippine Colleges in Batangas City, who disappeared after a protest rally in March 1984, and whose mangled bodies were later discovered abandoned in nearby Cavite province.[17]

Recent history

After the ouster of Ferdinand Marcos and the creation of the Fifth Philippine Republic, numerous Batanguenos took up prominent positions in government - most prominently Salvador Laurel, who became Vice President of the Philippines under the first Aquino administration, and Renato Corona, who became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines.[18]

Geography

(2018-02-01).jpg.webp)

Batangas is a combination of plains and mountains, including one of the world's smallest volcanoes, Mt. Taal, with an elevation of 600 metres (2,000 ft), located in the middle of the Taal Lake. Other important peaks are Mount Macolod with an elevation of 830 metres (2,720 ft), Mt. Banoy with 960 metres (3,150 ft), Mt. Talamitam with 700 metres (2,300 ft), Mt. Pico de Loro with 664 metres (2,178 ft), Mt. Batulao with 693 metres (2,274 ft), Mt. Manabo with 830 metres (2,720 ft), and Mt. Daguldol with 672 metres (2,205 ft).

Batangas has several islands, including Tingloy, Verde Island (Isla Verde), and Fortune Island of Nasugbu.

According to Guinness World Records, the largest island in a lake on an island is situated in Batangas (particularly at Vulcan Point in Crater Lake, which rests in the middle of Taal Island in Lake Taal, on the island of Luzon).

Administrative divisions

Batangas comprises 30 municipalities and 4 cities.

- † Provincial capital and component city

- ∗ Component city

- Municipality

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Climate

Batangas falls under two climates: the tropical savanna climate (As/Aw) and the bordering tropical monsoon climate (Am), under the Köppen climate classification. Most of the province belongs to the tropical savanna climate, with well-defined dry and wet seasons. Parts of Batangas lying to the east have unpronounced dry and wet seasons, influenced by the monsoon. Batangas City, the provincial capital, belongs to the tropical savanna climate, but is strongly influenced by the bordering monsoon climate, characterized by short dry seasons and longer wet seasons. Typhoons are a periodic occurrence especially during the southwest monsoon (habagat).

Demographics

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [2] [20] [21] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The population of Batangas in the 2015 census was 2,694,335 people, [2] with a density of 860 inhabitants per square kilometre or 2,200 inhabitants per square mile.

Tagalogs are the predominant people in Batangas, distantly followed by Bicolanos, Visayans, Kapampangans, Pangasinans and Ilocanos.[22]

Batangas also has one of the highest literacy rates in the country at 96.5%, with males having a slightly higher literacy rate at 97.1% than females with 95.9%. Combined average literacy rate is 96%.

Language

The dialect of Tagalog spoken in the province closely resembles the Old Tagalog spoken before the arrival of the Spanish. Hence, the Summer Institute of Linguistics called this province the heartland of the Tagalog language. A strong presence of the Tagalog culture is clearly visible to the present day.

Linguistically, Batangueños are also known for their unique affectation of often placing the particles eh or ga (equivalent to the particle ba in Filipino), usually as a marker of stress on the sentence, at the end of their spoken sentences or speech; for example: "Ay, oo, nga eh!" ("Aye, yes, indeed!"). Some even prolong the particle 'eh' into 'ala eh', though it really has no meaning in itself.

English is widely understood in the province. Spanish is also understood to some extent, especially by older generation people in the towns of Nasugbu, Taal, and Lemery, which still have Spanish-speaking minorities. Bicolano and Visayan is also spoken by a minority due to the influx of migrants from Bicol Region and Central Philippines.

Religion

The majority of Batangas's population are religiously affiliated with Roman Catholicism, Iglesia Filipina Independiente, Iglesia ni Cristo, and evangelicalism.[23] Other major religions include Islam, Buddhism, Seventh-day Adventist Church, Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide, Protestantism, Jehovah's Witnesses, and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Economy

The province of Batangas was billed as the third richest province in the Philippines by the Commission on Audit by year 2017 from fourth place in . That year, its provincial government posted a record high of ₱15.568 billion worth of assets, the largest in Calabarzon and the whole Luzon.

Products

Batangas is known for its butterfly knives, locally known as balisong, with its manufacture also becoming an industry in the province.

Agriculture and fisheries

Pineapples are also common in Batangas. Aside from the fruit, the leaves are also useful such that an industry has been created from it. In the municipality of Taal, pineapple leaves are processed to form a kind of cloth known as jusi (pronounced 'hu-si), from which the Barong Tagalog, the national costume of the Philippines is made.

Livestock as an industry is also thriving in Batangas. Cattle from Batangas are widely sought throughout the country. The term bakang Batangas (literally "Batangas cow") is associated with the country's best species of cattle. Cattle raising is widely practiced in Batangas such that every Saturday is an auction day in the municipalities of San Juan, Bauan and Padre Garcia.

Fishing plays a very important part of the economy of the province. Although the tuna industry in the country is centered in General Santos, Batangas is also known for the smaller species of the said fish. The locals even have their own names for it. Some of them are bigeye tuna (tambakol), yellowfin tuna (berberabe), tambakulis, Pacific bluefin tuna (tulingan), bullet tuna (bonito) and another species also called bonito but actually Gymnosarda unicolor. There is also an important industry for the wahoo (tanigi).

Aside from the South China Sea, Taal Lake also provides a source of freshwater fishes to the country. The lake is home to Sardinella tawilis or simply tawilis, a species of freshwater sardine that is endemic to the lake. Taal Lake also provides farmed Chanos chanos or bangus. There is also a good volume of Oreochromis niloticus niloticus and Oreochromis aureus, both locally called tilapia. It is ecologically important to note that neither bangus nor tilapia are native to the lake. Thus they are considered an invasive species to the lake.

Sugar is also a major industry. After Hacienda Luisita, the country's former largest sugar producer, was broken-up for land reform, the municipality of Nasugbu has been the home of the current largest sugar producing company, the Central Azucarera de Don Pedro. Rice cakes and sweets are also a strong industry.

Some towns (those adjacent to Laguna) have a prosperous bamboo based industry, where several houses and furniture are made of bamboo. Natives say that food cooked in bamboo has an added scent and flavor. Labong, or bamboo shoots, is cooked with coconut milk or with other ingredients to make a Batangas delicacy.

Industries

Batangas houses 5 industrial parks registered under the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA), which are concentrated along the route of STAR Tollway and Jose P. Laurel Highway. The largest of those industrial parks are LIMA Technology Center, a 500-hectare (1,200-acre) commercial and industrial zone oriented to tech companies at Lipa and Malvar, and the First Philippine Industrial Park (FPIP), with over 350 hectares (860 acres) at Santo Tomas and Tanauan, and Light Industry and Science Park IV (LISP IV), a live-work community with 170-hectare industrial area located at the heart of Malvar, Batangas.

Batangas City and the nearby municipalities of San Pascual, Bauan, and Mabini also have large-scale industrial activity connected with their seaside location, including power generation, oil and gas processing and transhipment, and ship repairs.

Government

.jpg.webp)

With the provinces in the island of Panay, Ilocos Sur and Pampanga, Batangas was one of the earliest provinces established by the Spaniards who settled in the country. It was headed by Martin de Goiti and since then has become one of the most important regions of the Philippines. Batangas first came to be known as Bonbon. It was named after Taal Lake, which was also originally called Bonbon. Some of the earliest settlements in Batangas were established in the vicinity of Taal Lake. In 1534, Batangas became the first practically organized province in Luzon. Balayan was the capital of the province for 135 years from 1597 to 1732. In 1732, it was moved to Taal, then the flourishing and most progressive town in the province, it wasn't until 1754 that the capital was destroyed by the Great Taal Eruption of 1754. It was in 1889 that the capital was moved to the present, Batangas City.

Batangas has been called by some Philippine historians as the "Cradle of Noble Heroes", citing the notable number of people from it who were declared Philippine national heroes and those who became leaders of the country. Among them are Teodoro M. Kalaw, Apolinario Mabini, Jose Laurel, and Felipe Agoncillo.

Incumbent officials

- Governor: Hermilando I. Mandanas (PDP–Laban)

- Vice Governor: Jose Antonio S. Leviste II (PDP–Laban)

- Board Members:

| Representation | Name | Name |

|---|---|---|

| First District | Carlo Roman G. Rosales (NP/One Batangas) | Glenda P. Bausas (NP/One Batangas) |

| Second District | Arlina B. Magboo (NP/One Batangas) | Wilson Leonardo T. Rivera (NP/One Batangas) |

| Third District | Jhoanna DC. Corona-Villamor (NP/One Batangas) | Rodolfo M. Balba (NP/One Batangas) |

| Fourth District | Jonas Patrick M. Gozos (NP/One Batangas) | Jesus H. De Veyra (NP/One Batangas) |

| Fifth District (Batangas City) | Ma. Claudette U. Ambida-Alday (NP/One Batangas) | Arthur G. Blanco (NP/One Batangas) |

| Sixth District (Lipa City) | Lydio A. Lopez, Jr (NP/One Batangas) | Aries Emmanuel D. Mendoza (NP/One Batangas) |

| Philippine Councilors League President | Ronald E. Cruzat | Bauan |

| Liga ng Mga Barangay President | Wilfredo M. Maliksi | Santo Tomas |

| Sangguniang Kabataan Provincial Fedration President | Maria Louise G. Vale | San Luis |

- Elected Representatives

- 1st District: Elenita Milagros R. Ermita-Buhain (NP/One Batangas)

- 2nd District: Raneo E. Abu (NP/One Batangas)

- 3rd District: Ma. Theresa V. Collantes (PDP–Laban)

- 4th District: Lianda B. Bolilia (NP/One Batangas)

- 5th District (Lone District of Batangas City): Mario Vittorio A. Mariño (NP/One Batangas)

- 6th District (Lone District of Lipa City): Ma. Rosa Vilma T. Santos-Recto (NP/One Batangas)

List of former governors

Infrastructure

Roads

Batangas has a total of 556 kilometers (345 mi) of national roads, mostly paved.[31] The Southern Tagalog Arterial Road (STAR Tollway, officially numbered E2), Maharlika Highway (N1 and AH26) and Jose P. Laurel Highway (N4) forms the highway backbone of the province, and a network of secondary and tertiary national roads links most of the municipalities. The provincial government maintains a network of provincial roads to supplement the national roads and connect municipalities and barangays not connected directly to the main highway network.

The Cavite-Tagaytay-Batangas (CTBEX) is a proposed expressway from the municipality of Silang, Cavite up to the town of Nasugbu. CTBEX is to connect with the Cavite–Laguna Expressway (CALAEX). Once opened, this will provide motorists a faster route to the resort towns of Nasugbu, Lian and Calatagan in the western part of the province.

Water transport

Batangas Port in Batangas City is the principal port for ferry access to Mindoro, Tablas, Romblon, and other islands. Montenegro Lines is the largest of a number of passenger shipping companies operating out of Batangas. Condensate tankers offload at Batangas in sizeable quantity. Batangas Port is expanded in 2008 to house facilities for container ships.

Being an entry point to the rest of the archipelago, Batangas has roll-on/roll-off(RoRo) ferry connections with Mindoro and Visayas. The western portion of the Nautical Highway starts at Batangas, and connects with Calapan, Oriental Mindoro. Batangas Port serves as another principal port, along with the Manila International Port for inter-island and international cargo shipping, as well as interisland passenger shipping.

Electricity

Electric power in Batangas is mostly distributed by electric cooperatives, namely the Batangas I Electric Cooperative (BATELEC-I) and Batangas II Electric Cooperative (BATELEC-II). The former serves the western part of Batangas, like Nasugbu, Calatagan, Balayan, Lemery, and Taal, while the latter serves the eastern part, like Lipa, Tanauan, Talisay, San Jose, and Rosario. The municipalities of Bauan and Ibaan, and LIMA Technology Center are served by local utility companies. Santo Tomas, the First Philippine Industrial Park (FPIP) in Tanauan, San Pascual and Batangas City, however, are served by the Metro Manila-based electric company, Meralco. Some large industrial customers are supplied by the 69,000 volt grid, operated by National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP), BATELEC-II, and Meralco.

Batangas houses three power plants that provide the bulk of power used in Luzon. Power plants include the 600-megawatt (MW) Calaca Coal Fired Power Plant in Calaca, the 500 MW, 1000 MW, and 414 MW San Lorenzo-Santa Rita-San Gabriel Combined Cycle Power Plant,[32] and the 1251 MW Ilijan Power Plant, both in Batangas City. The Calaca Power Plant is originally built with nameplate capacity of 600 MW, is being expanded to generate 1300 MW, with an addition of 2x350 MW (700 MW) capacity in a second power plant, constructed under an agreement between Semirara Mining and Meralco.[33]

Most power plants in Batangas, however, use fossil fuels, such as coal and natural gas, and are the subjects of environmental grievances because of their effects on ecosystems. One power plant to be built at Mabacong, Batangas City, is facing opposition from environmentalists and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lipa, owing to its effect on residents and the aquatic ecosystem on Verde Island Passage.[34]

Culture

Way of life

Maria Kalaw Katigbak, a Filipino historian, was quoted to call the Batangueños the Hybrid-Tagalogs. One particular custom in the Batangas culture is the so-called Matanda sa Dugo (lit. older by blood) practice wherein one expresses respect not because of age but because of consanguinity. During the early times, the custom of having very large families were very common. Thus, a particular person's uncle could be of the same age, or even younger than himself. Because of the custom, the older person would still address the younger one with an honorary title such as tiyo/tio or simply kuya if they can no longer establish the actual relationship or add the honorific ho / po in their sentences when addressing the younger instead of the other way around. This often draws confusion from the other provinces who are not accustomed to such practices. This practice exists until today.

Batangueños are very "regionalistic". When one learns that another in the room is also from Batangas, the two would be together until the end of the event. In workplace settings, a Batangueno may also express preference for another Batangueno as long as the workplace regulations allow. Thus, the running joke on the Batangas Mafia.

They also tend to live in a large extended family. It has been observed that a piece of land remains undivided until the family connection becomes too difficult to establish actual blood relations. Marriages between relatives of the fifth generation is still restrained in the Batangan culture even if Philippine laws allow it.

Batangueños have been known for their religious practices, where devotees of the Catholic religion perform rituals such as dances (subli) and chants (luwa/lua) to express their faith. One of these is the ritual called Pasión/Pasyon based on the passion of Jesus Christ in which religious chants are recited during the Lenten season. In May, the people of Bauan and Alitagtag celebrate the feast day of the Mahal na Poon ng Santa Cruz (lit. Lord of the Holy Cross), a ritual dance called the Subli is made to honor the Poon. In the town of Taal, they celebrate the feast day of Our Lady of Caysasay and San Martin de Tours a two-day celebration where a procession begins from the shrine of the Virgin going towards the Pansipit River from which the fluvial procession and another procession towards the Basilica are made in honor of the Virgin Mary. Fiestas in other towns usually start in the month of May and last up to the first day of June, usually the plaza near the church becomes the center of activities.

Mythology and literature

Scholars also identified that the ancient Batangueños, like the rest of the Tagalog tribe, worship the Supreme Creator, known as Bathala. Lesser gods like Mayari, the goddess of the moon and her honorary brother Apolake, god of the sun, were also present. Dambana practices are also present in the province.

For literature, Padre Vicente Garcia came to be known when he wrote an essay to defend José Rizal's Noli Me Tangere.

In 2004, the province of Batangas gave Domingo Landicho (familiarly called Inggo by Batangueños) who was born in the province the Dangal ng Batangas (Pride of Batangas) Award for being the "Peoples' Poet".

Music

Musicologists identified Batangas as the origin of the kumintang, an ancient war song, which later evolved to become the signature of Filipino love songs the kundiman. From the ancient kumintang, another vocal music emerged, identified as the awit. The huluna, a psalm-like lullaby, is also famous in some towns, especially Bauan.

During the Lenten Season, the Christian passion-narrative, called Pasyon by the natives, is expected in every corners of the province. In fact according to scholars, the very first printed version of the pasyon was authored by a layman from Rosario named Gaspar Aquino de Belen. Although de Belen's version was printed in 1702, it is still debated whether there were earlier versions.

Debates may also be done while singing. Batangueños are known for the duplo (a sung debate where each lines of the verse must be octosyllabic) and the karagatan (a sung debate where each lines of the verse must be dodecasyllabic.) The latter, whose literal meaning is "ocean", got its name from the opening lines. Always, the karagatan is opened by saying some verses that alludes the depth of the sea and comparing it to the difficulty of joining the debate. And as mentioned above, the debate must be sung.

Batangas is also the origin of the Balitao. Aside from being a form of vocal music, the Balitao is also a form of dance music. The Balitao, together with the Subli is the most famous form of dance native to Batangas.

Architecture and sculpture

As shown in its ancient churches, Batangas is home to some of the best preserved colonial architectures in the country, especially evident in the municipality of Taal.

Though not as popular as the carving industry of Laguna, Batangas is still known for the sculptures engraved in furniture. Sometimes, altar tables coming from Batangas were called the "friars' choice".

According to Milagros Covarubias-Jamir, another Filipino scholar, the furniture that came from Batangas during the colonial times was comparable to equivalent quality furniture from China. The build of the furniture was so exquisite, nails of glues were never used. Still, the Batangueños knew how to maximize the use of hardwoods. As a result, furniture made about a hundred years ago are still found in many old churches and houses even today.

Museums

- Museo ng Katipunan: Barangay Bulaklakan, Lipa

- Apolinario Mabini Shrine: Marcela Agoncillo Historical Landmark, Barangay zone 4, Taal, Batangas

- Miguel Malvar Hospital: Leon Apacible Historical Landmark, Santo Tomas, Batangas

- Museo ng Batangas at Aklatang Panlalawigan: includes the Dr. Jose P. Laurel Library, Tanauan, Batangas

Flora and fauna

The malabayabas, or Philippine Teak, is endemic to Batangas. The province is also home to the kabag (Haplonycteris fischeri), one of the world's smallest fruit bats. In the municipality of Nasugbu, wild deer still inhabit the remote areas of barangay Looc, Papaya, Bulihan, and Dayap.

In the second half of 2006, scientists from the United States discovered that the Sulu-Sulawesi Triangle has its centre at the Isla Verde Passage, a part of the province. According to the study made by the American Marine Biologist Dr. Kent Carpentier, Batangas' seas host more than half of the world's species of coral. It is also home to dolphins and once in a while, the passage of the world's biggest fish: the whale shark or the butanding, as the locals call it may be observed. The municipality of San Juan has a resident marine turtle or pawikan. Pawikans like the Olive Ridley sea turtle, leather back sea turtle, and green sea turtle can be seen in Nasugbu up to the present.

Notable people

- Apolinario Mabini — Filipino revolutionary

- Miguel Malvar — Filipino general who served during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War

- Felipe Agoncillo — the Filipino lawyer representative to the negotiations in Paris that led to the Treaty of Paris (1898)

- Marcela Agoncillo — the principal seamstress of the first and official flag of the Philippines

- Ananias Diokno — Filipino general in the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War

- José P. Laurel — president of the Second Philippine Republic, a Japanese puppet state during World War II

- Loren Legarda — Filipino environmentalist, journalist and politician

- Salvador Laurel — Vice-President of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992 under Corazon Aquino

- Gaudencio Rosales - Filipino Cardinal and Archbishop who has served as the 31st Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Manila, 6th Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Lipa, Batangas and 2nd Bishop of the Diocese of Malaybalay, Bukidnon.

- Reynaldo Gonda Evangelista - Filipino Roman Catholic Bishop who is currently serving in the Diocese of Imus. He was a former Bishop of Boac, Marinqudue

- Cecilia Muñoz-Palma - Filipino jurist and the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

- Teodoro Agoncillo — Filipino historian

- Maria Orosa — Filipino food technologist, pharmaceutical chemist

- Fernando Suarez — Filipino Catholic priest who performs faith healing

- Ai-Ai delas Alas — Filipino actress, comedian, singer and TV host

- Ogie Alcasid — Filipino singer-songwriter, television presenter, comedian, parodist, and actor

- Leo Martinez — Filipino actor, comedian and director

- Zanjoe Marudo — Filipino actor and model

- Jason Gainza — Filipino actor, impersonator

- Joshua Garcia — Filipino actor, model and endorser

- Alyssa Valdez – is a Filipino volleyball player. She was a member of the collegiate varsity volleyball team of Ateneo de Manila University in both indoor and beach volleyball.

- Kim Fajardo – is a Filipino volleyball athlete. She is a former team captain of the De La Salle University women's volleyball team.

References

- "List of Provinces". PSGC Interactive. Makati City, Philippines: National Statistical Coordination Board. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- de Navarrete, Martín Fernández (1831). Diccionario Marítimo Español. Imprenta Real. p. 401.

- Bureau of Insular Affairs (1902). A Pronouncing Gazetteer and Geographical Dictionary of the Philippine Islands: Also The Law of Civil Government in the Philippine Islands. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 345.

- Horridge, G. Adrian (1982). The Lashed-lug Boat of the Eastern Archipelagoes, the Alcina MS and the Lomblen Whaling Boats. Trustees of the National Maritime Museum. pp. 18–21. ISBN 9780905555614.

- "tribhanga". Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- http://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-01-01-1963/Francisco%20Buddhist.pdf

- Batangas Airport in Barangay Alaingilan destroyed after Japanese air raids Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Lt. César Basa's actions at the Japanese Air Raids in the Batangas Airfield

- Christine Sherman, M.J. Thurman, War Crimes, Japan's World War II, p.136

- "Landing Craft Infantry LCI".

- "HyperWar: US Army in WWII: Triumph in the Philippines [Chapter 23]".

- Flanagan, Jr., Lt. Gen. E. M. (1989). The Angels: A History of the 11th Airborne Division. San Francisco: Presidio Press. p. 480. ISBN 0891413588.

- administrator (2015-10-15). "DIOKNO, Jose W." Bantayog ng mga Bayani. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Romero, Paolo. "Enrile apologizes to Martial Law victims, blames 'unlucid intervals'". philstar.com. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Ayroso, Dee (2016-04-20). "Marcos era saw most rapid environmental degradation, biodiversity loss". Bulatlat. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Contributor, Staff (2016-04-25). "UMALI, Ismael G." Bantayog ng mga Bayani. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20201020175113/http://www.batangas.gov.ph/portal/history/

- "Province: Batangas". PSGC Interactive. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities (PDF). NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region IV-A (Calabarzon)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- "Batangas: Close to Two Million People". Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- "Batangas Statistical Tables (2015)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/NSCB_LocalPovertyPhilippines_0.pdf; publication date: 29 November 2005; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2009%20Poverty%20Statistics.pdf; publication date: 8 February 2011; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/Table%202.%20%20Annual%20Per%20Capita%20Poverty%20Threshold%2C%20Poverty%20Incidence%20and%20Magnitude%20of%20Poor%20Population%2C%20by%20Region%20and%20Province%20%20-%202006%2C%202009%2C%202012%20and%202015.xlsx; publication date: 27 August 2016; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/Table%202.%20%20Annual%20Per%20Capita%20Poverty%20Threshold%2C%20Poverty%20Incidence%20and%20Magnitude%20of%20Poor%20Population%2C%20by%20Region%20and%20Province%20%20-%202006%2C%202009%2C%202012%20and%202015.xlsx; publication date: 27 August 2016; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/Table%202.%20%20Annual%20Per%20Capita%20Poverty%20Threshold%2C%20Poverty%20Incidence%20and%20Magnitude%20of%20Poor%20Population%2C%20by%20Region%20and%20Province%20%20-%202006%2C%202009%2C%202012%20and%202015.xlsx; publication date: 27 August 2016; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/Table%202.%20%20Updated%20Annual%20Per%20Capita%20Poverty%20Threshold%2C%20Poverty%20Incidence%20and%20Magnitude%20of%20Poor%20Population%20with%20Measures%20of%20Precision%2C%20by%20Region%20and%20Province_2015%20and%202018.xlsx; publication date: 4 June 2020; publisher: Philippine Statistics Authority.

- Figures tabulated from 2015 road data for Region IV-A by Department of Public Works and Highways

- "Our Power Plants". First Gen. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Rivera, Danessa (April 29, 2016). "Semirara Mining, Meralco seal partnership for Calaca plant expansion". The Philippine Star. Philstar. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- "Batangas priests lead fight vs. coal-fired power plant". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

External links

Media related to Batangas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Batangas at Wikimedia Commons Batangas travel guide from Wikivoyage

Batangas travel guide from Wikivoyage Geographic data related to Batangas at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Batangas at OpenStreetMap- Official Website of the Provincial Government of Batangas