Skenfrith Castle

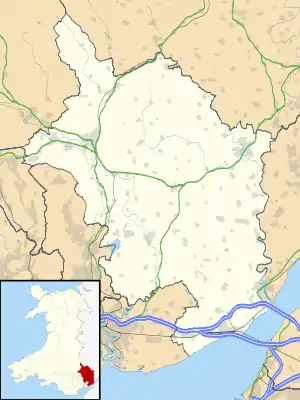

Skenfrith Castle (Welsh: Castell Ynysgynwraidd) is a ruined castle in the village of Skenfrith in Monmouthshire, Wales. The fortification was established by the Normans in the wake of the invasion of England in 1066, to protect the route from Wales to Hereford. Possibly commissioned by William fitz Osbern, the Earl of Hereford, the castle comprised earthworks with timber defences. In 1135, a major Welsh revolt took place and in response King Stephen brought together Skenfrith Castle and its sister fortifications of Grosmont and White Castle to form a lordship known as the "Three Castles", which continued to play a role in defending the region from Welsh attack for several centuries.

| Skenfrith Castle | |

|---|---|

| Skenfrith, Monmouthshire, Wales | |

The keep and castle interior | |

Skenfrith Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.8784°N 2.7902°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Controlled by | Cadw |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Red sandstone |

| Events | Norman invasion of Wales |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

At the end of the 12th century, Skenfrith was rebuilt in stone. In 1201, King John gave the castle to a powerful royal official, Hubert de Burgh. During the course of the next few decades, it passed back and forth between several owners, including Hubert, the rival de Braose family, and the Crown. Hubert levelled the old castle and built a new rectangular fortification with round towers and a circular keep. In 1267 it was granted to Edmund, the Earl of Lancaster, and remained in the hands of the earldom, and later duchy, of Lancaster until 1825.

Edward I's conquest of Wales in 1282 removed much of Skenfrith Castle's military utility, and by the 16th century it had fallen into disuse and ruin. The castle was placed into the care of the state by the National Trust in 1936, and is now managed by the Cadw heritage agency.

History

11th–12th centuries

Skenfrith Castle was built in the wake of the Norman invasion of England in 1066.[1] Shortly after the invasion, the Normans pushed up into the Welsh Marches, where William the Conqueror made William fitz Osbern the Earl of Hereford; Earl William added to his new lands by then capturing the towns of Monmouth and Chepstow.[2] The Normans used castles extensively to militarily subdue the Welsh, establish new settlements and exert their claims of lordship over the territories.[3]

Skenfrith Castle was one of a triangle of fortifications built in the Monnow valley around this time, possibly by Earl William himself, to protect the route from Wales to Hereford.[4] The first castle on the site was built from earth and timber.[4]

The earldom's landholdings in the region were slowly broken up after William's son, Roger de Breteuil, rebelled against the King in 1075.[4] In 1135, a major Welsh revolt took place, however, and in response King Stephen restructured the landholdings along this section of the Marches, bringing together Skenfrith Castle and its sister fortifications of Grosmont and White Castle back under the control of the Crown to form a lordship known as the "Three Castles".[4]

Conflict with the Welsh continued, and following a period of détente under Henry II in the 1160s, the de Mortimer and de Braose Marcher families attacked their Welsh rivals during the 1170s, leading to a Welsh assault on nearby Abergavenny Castle in 1182.[5] In response, the Crown readied the castle to face an attack, and in 1186, £43[nb 1] was spent developing the defences followed by more work in 1190, probably establishing a stone keep and curtain wall.[7]

13th–17th centuries

In 1201, King John gave the Three Castles to Hubert de Burgh.[8] Hubert was a minor landowner who had become John's household chamberlain when he was still a prince, and went on to become an increasingly powerful royal official once John had inherited the throne.[9] Hubert began to upgrade his new castles, starting with Grosmont, but was captured while fighting in France.[8] While Hubert was in captivity, King John took back the Three Castles and gave them to William de Braose, a rival of Hubert's.[9] King John subsequently fell out with William and dispossessed him of his lands in 1207, but de Braose's son, also called William, took the opportunity presented by the First Barons' War to retake the castles.[10]

Once released, Hubert regained his grip on power, becoming the royal justiciar and being made the Earl of Kent, before finally recovering the Three Castles in 1219 during the reign of King Henry III.[10] During Hubert's tenure, Skenfrith was entirely rebuilt; the old castle was levelled and a new rectangular castle with round towers and a central circular keep was constructed in its place.[8]

Hubert fell from power in 1232 and was stripped of the castles, which were placed under the command of Walerund Teutonicus, a royal servant; having been reconciled with the king in 1234, the castles were returned to him briefly but he fell out with King Henry III again in 1239 and they were taken back once again and assigned to Walerund.[11] Walerund built a new chapel at the castle in 1244, and repaired the keep's roof.[12] In 1254, Skenfrith Castle and its sister fortifications were granted to King Henry's eldest son, and later king, Prince Edward.[12]

The Welsh threat persisted, and in 1262 the castle was readied in response to Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd's attack on Abergavenny in 1262; commanded by its constable Gilbert Talbot, Skenfrith was ordered to be garrisoned "by every man, and at whatever cost".[12] The threat passed without incident.[12]

Edmund, the Earl of Lancaster and the capitaneus of the royal forces in Wales, was given the Three Castles in 1267 and for many centuries they were held by the earldom, later duchy, of Lancaster.[13] Little further work was carried out at Skenfrith, although repairs were carried out to the tower and gates under King Henry VI.[14] King Edward I's conquest of Wales in 1282 had removed much of the castle's military utility, although it continued to be used as an administrative centre.[15] By 1538, Skenfrith Castle had fallen into disuse and then into ruin; a 1613 description noted that it was "ruynous and decayed".[14]

18th–21st centuries

In 1825, the Three Castles were sold off to Henry Somerset, the Duke of Beaufort.[16] It was eventually acquired by the lawyer Harold Sands, who carried out some conservation of the site; he went on to give the castle to the National Trust.[17] Skenfrith was placed into the care of the state in 1936, and extensive repair work was carried out.[17] In the 21st century, Skenfirth Castle is managed by Cadw and protected under UK law as a grade II* listed building.[18]

Architecture

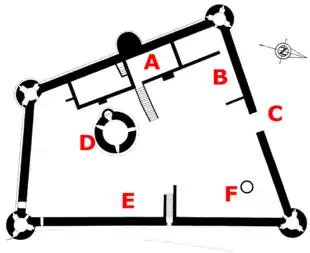

Skenfrith Castle was constructed alongside the River Monnow. The current castle was created by Hubert de Burgh in the early 13th century, when the earthworks of the 11th-century Norman castle were flattened and spread out over the current site to a depth of 12 feet (3.7 m); the 12th-century stone fortifications and buildings were demolished at the same time.[19] Hubert's castle forms a polygon, with four walls approximately 80 metres, 60 metres, 60 metres and 40 metres (260 ft, 200 ft, 200 ft and 130 ft) long respectively, and was built from Old Red Sandstone.[20] It was originally protected by a stone-revetted, water-filled moat, 9 feet (2.7 m) deep and 46 feet (14 m) wide, fed by the river.[21] The moat is now filled in and grassed over.[21] The castle was entered from the north-west side over a bridge and through a gatehouse, both since destroyed.[19]

The curtain wall survives to a height of up to 5 metres (16 ft 5 in), and was probably originally topped by a 6-foot-high (1.8 m) parapet and protective timber hoarding.[22] The castle had circular towers on each corner, probably only used for storage and defence, of which three still survive, the north-west tower having been reduced to its foundations.[23] A watergate on the eastern side of the castle led down to the Monnow.[24]

A two-storey hall range stretched across the south-western inside of the castle, of which only the foundations now survive.[25] Originally the hall range comprised a long room on the northern end, and a smaller chamber to the south, although the northern section was subsequently subdivided.[25] The floor level of the hall range was later raised due to flooding, with the ground floors being filled in with gravel.[25] The main hall would have been on the first floor, above the surviving ground floor fireplace.[26] The south end of the range held a water reservoir for the castle.[26] On the opposite side of the hall range was a kitchen block, of which nothing now survives above ground.[27]

The three-story circular keep in the middle of the castle is 12 metres (39 ft 4 in) high and 10 metres (32 ft 10 in), across with a protruding staircase tower on its south-western side.[28] It closely resembled similar keeps built during this period in France by Philip II and at Pembroke by William Marshal; its staircase tower was similar to others built across the Welsh Marches at the time, including at Caldicot and Longtown.[29] Earth was piled up around the 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) plinth at the base of the keep, probably to defend the base of the walls, with the result closely resembling a motte.[28] Originally it would have been topped with defensive wooden hoarding, with an external wooden staircase reaching up to the entrance on the first floor: the current, ground floor entrance was cut out of its walls at a later date.[30] The basement was accessed by a trapdoor and used as a storeroom.[31] The first floor chamber would have been an antechamber, while the second floor chamber was fitted with windows, a large fireplace and a private latrine, and would have provided living accommodation for the lord.[30]

Notes

- Comparison of medieval financial figures with modern equivalents is notoriously challenging. For comparison, the average annual income of a baron during this period was around £200.[6]

Notes

- Knight 2009, pp. 3–4

- Knight 2009, p. 3

- Davies 2006, pp. 41–44

- Knight 2009, p. 4

- Knight 2009, p. 5; Holden 2008, p. 143

- Pounds 1994, p. 147

- Knight 2009, p. 5

- Knight 2009, p. 7

- Knight 2009, p. 7; West, F. J. (2008), "Burgh, Hubert de, earl of Kent (c.1170–1243), justiciar" (Online ed.), Oxford University Press

- Radford 1962, p. 4; Knight 2009, p. 7

- Knight 2009, pp. 10–11

- Knight 2009, p. 11

- Knight 2009, p. 12; Taylor 1961, p. 174

- Knight 2009, p. 14

- Knight 2009, pp. 12–13

- Knight 2009, p. 15

- Radford 1959, p. 3

- "Full Report for Listed Buildings", cadw, retrieved 24 October 2017

- Knight 2009, pp. 27–28

- Knight 2009, pp. 27–28; "Full Report for Listed Buildings", cadw, retrieved 24 October 2017

- Knight 2009, p. 27

- Knight 2009, p. 28; "Full Report for Listed Buildings", cadw, retrieved 24 October 2017

- Knight 2009, pp. 28–29

- Knight 2009, p. 29

- Knight 2009, p. 33

- Knight 2009, p. 34

- Knight 2009, pp. 34–35

- Knight 2009, p. 30; "Full Report for Listed Buildings", Cadw, retrieved 24 October 2017

- Knight 2009, p. 32; Goodall 2011, p. 181

- Knight 2009, p. 30

- Knight 2009, p. 30; Radford 1959, p. 6

Bibliography

- Davies, R. R. (2006) [1990]. Domination and Conquest: The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100–1300. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52102-977-3.

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle, 1066–1650. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30011-058-6.

- Holden, Brock W. (2008). Lords of the Central Marches: English Aristocracy and Frontier Society, 1087–1265. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954857-6.

- Knight, Jeremy K. (2009) [1991]. The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle (revised ed.). Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-266-1.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Radford, C. A. Ralegh (1959) [1949]. Skenfrith Castle, Monmouthshire. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 27818100.

- Radford, C. A. Ralegh (1962). White Castle, Monmouthshire. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 30258313.

- Taylor, A. J. (1961). "White Castle in the Thirteenth Century: A Re-Consideration". Medieval Archaeology. 5: 169–175.