Skylab controversy

A work slowdown, characterized by some writers as the Skylab strike, Skylab mutiny or the Skylab controversy, was instigated during some or all of December 28, 1973 by the crew of Skylab 4—the last of the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Skylab missions.[1][2] According to Michael Hiltzik, the three astronauts, Gerald P. Carr, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue, turned off radio communications with NASA ground control and spent time relaxing and looking at the Earth before resuming communication with NASA,[2] refusing communications from mission control during this period. Once communications resumed, there were discussions between the crew and NASA. The mission continued for several more weeks before the crew returned to Earth in 1974. The 84-day mission was Skylab's last crew, and the last time American astronauts set foot in a space station for two decades, until Shuttle–Mir in the 1990s.

The event, which the involved astronauts have joked about,[3] has been extensively studied as a case study in various fields of endeavor including space medicine, team management, and psychology. Man-hours in space were, and continued to be into the 21st century, a profoundly expensive undertaking; a single day on Skylab was worth about $22.4 million in 2017 dollars, and thus any work stoppage was considered inappropriate due to the expense.[4] According to Space Safety Magazine, the incident affected the planning of future space missions, especially long-term missions.[5]

The exact nature of what happened, or whether anything happened at all, is controversial. Spaceflight history author David Hitt disputed that the crew purposefully ended contact with mission control in a book written with former astronauts Owen K. Garriott and Joseph P. Kerwin.[6]

Background and causes

| Mission |

|

|---|---|

| Skylab 2 | 28 |

| Skylab 3 | 60 |

| Skylab 4 | 84 |

On December 28, 1973, NASA Mission Control in Houston, Texas, could not communicate with Skylab 4 for about 90 minutes, about one full orbit of Earth, when there should have been radio contact. The existence and cause of the communications gap is the controversy. Behavioral problems during a spaceflight are of concern to mission planners because they can cause a mission to fail.[7] NASA has studied matters that affect crew social dynamics such as morale, stress management, and how the crew solves problems as a group with missions like HI-SEAS.[8] Each Skylab pushed farther into the unknown of space medicine, and it was difficult to make predictions about the reaction of the human body to prolonged weightlessness.[9] The first crewed Skylab mission set a spaceflight record with its 28-day mission, and Skylab 3 roughly doubled that to 59 days; no one had spent this long in orbit.[9]

Possible contributing factors to the incident include:[10]

- Twelve-week length of stay (the longest stay yet attempted by astronauts up to that time)

- Isolated environment

- Design of the spacecraft

- Microgravity environment

- Workload expectations of Skylab team

- Workload expectations of mission control

- Crew inexperience (all first-time astronauts)

- No transition period

Three three-man crews spent progressively longer amounts of time (28, 60, and then 84 days), launched to orbit by the Saturn IB and flying the Apollo CSM spacecraft to the station.[11] It was visited by three three-man crews, and the incident occurred on this last all-rookie mission, which was also the longest.[12]

Skylab 3 had finished all their work and asked for more work; this may have led NASA to have a higher expectation for the next crew.[13] However, the next crew were all "rookies" (they had not been in space before) and may not have had the same concept of workload as the previous crew.[13] Both previous crews had veteran members and both previous crews had one member that had been to the Moon and back.[13] Another factor was that the rookie astronauts were in denial about their problems and hid the issues they were having with mission control, leading to even higher mental strain.[13] The crew increasingly became bothered by having every hour of their trip duration scheduled.[14]

Event

NASA had continued with a workload similar to that on the shorter Skylab 3,[15] and the crew gradually fell behind on their workload. According to Michael Hiltzik, after six weeks the crew announced a "strike" and turned off all communication with ground control for December 28, 1973.[2] To date, no evidence of this announcement has been located in mission transcripts or audio recordings of the flight.

According to Henry S. F. Cooper, the crew were alleged to have stopped working. Gibson spent his day on Skylab's solar console, while Carr and Pogue spent their time in the wardroom looking out the window.[16]

Spaceflight history author David Hitt disputed that the crew deliberately ended contact with mission control in a book written with former astronauts Owen K. Garriott and Joseph P. Kerwin.[6]

Effects

At the time, only the crew of Skylab 3 had spent six weeks in space. It was unknown what had happened psychologically. NASA carefully worked with crew's requests, reducing their workload for the next six weeks. The incident took NASA into an unknown realm of concern in the selection of astronauts, still a question as humanity considers human missions to Mars or returning to the Moon.[18]

After the incident, there were many attempts to either determine the cause or downplay what happened.[13] Nevertheless, lessons learned focused on balancing workload with crew psychology and stress level.[13] One factor that affects disaster planning is the process of lessons learned from past incidents.[19] Two contrasting pressures are the desire to hide a problem to avoid issues such as reprimands versus the honest evaluation of the issue to prevent future occurrences.[19]

Among the complicating factors was the interplay between management and subordinates (see also Apollo 1 fire and Challenger disaster). On Skylab 4, one problem was that the crew was pushed even harder as they fell behind on their workload, creating an increasing level of stress.[20] Even though none of the astronauts returned to space, there was only one more NASA spaceflight in the decade and Skylab was the first and last American space station.[12] NASA was planning larger space stations but its budget shrank considerably after the Moon landings, and the Skylab orbital workshop was the only major execution of Apollo Applications projects.[12]

Though the final Skylab mission became known for the incident, it was also known for the large amount of work that was accomplished in the long mission.[5] Skylab orbited for six more years before its orbit decayed in 1979 due to higher-than-anticipated solar activity.[13] The next U.S. spaceflight was the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project conducted in July 1975, and after a human spaceflight gap, the first Space Shuttle orbital flight STS-1.

The described events were considered a significant example of "us" versus "them" syndrome in space medicine.[15] Crew psychology has been a point of study for Mars analog missions such as Mars-500, with a particular focus on crew behavior triggering a mission failure or other issues.[15] One of the impacts of the incident is the requirement that at least one member of the International Space Station crew be a space veteran (not be on a first flight).[21]

The 84-day stay of the Skylab 4 mission was a human spaceflight record that was not exceeded for over two decades by a NASA astronaut.[22] The 96-day Soviet Salyut 6 EO-1 mission broke Skylab 4's record in 1978.[23][24]

Controversies

Sources including David Hitt's Homesteading Space[6] and Atlas Obscura[25] dispute that the crew purposefully ended contact with mission control.

See also

References

- Broad, William J. (July 16, 1997). "On Edge in Outer Space? It Has Happened Before". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Hiltzik, Michael. "The day when three NASA astronauts staged a strike in space". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- Vitello, Paul (March 10, 2014). "William Pogue, Astronaut Who Staged a Strike in Space, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Lafleur, Claude (March 8, 2010). "Costs of US Piloted Programs". The Space Review. Retrieved February 18, 2012. See author's correction in comments section.

- "All the King's Horses: The Final Mission to Skylab (Part 3)". Space Safety Magazine. 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- Hitt, David (2008). Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803219014. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Behavioral Problems in Early Human Spaceflight". Spacesafetymagazine.com. 2015-08-29. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- Howell, Elizabeth (2015-03-03). "Mars on Earth: Mock Space Mission Examines Trials of Daily Life". Space.com. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- "Second crew on Skylab: Breaking all records". Sen.com. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- "Case Study 2 - In the HBS case Strike in Space the Skylab space station cut off communication by turning off the radio and refusing to talk with Houston". www.coursehero.com. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- "Skylab 4 Rang in the New Year with Mutiny in Orbit". Motherboard. Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- "Skylab: Everything You Need to Know". www.armaghplanet.com. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- "Skylab: First U.S. Space Station". Space.com. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- Hollingham, Richard (December 21, 2015). "How the Most Expensive Structure in the World was Built". BBC. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Clément, Gilles (2011-07-15). Fundamentals of Space Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-9905-4.

- Cooper, Henry S. F. (August 30, 1976). "Life in a Space Station". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

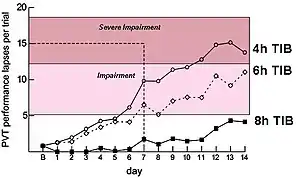

- Van Dongen, HP; Maislin, G; Mullington, JM; Dinges, DF (2003). "The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation". Sleep. 26 (2): 117–26. doi:10.1093/sleep/26.2.117. PMID 12683469.

- DNews (2012-04-16). "Why 'Space Madness' Fears Haunted NASA's Past". Seeker – Science. World. Exploration. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- "James Oberg's Pioneering Space". www.jamesoberg.com. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- Staff, Wired Science. "Skylab: America's First Home in Space Launched 40 Years Ago Today". WIRED. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- Gilles Clément (2011). Fundamentals of Space Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4419-9905-4.

- Elert, Glenn. "Duration of the Longest Space Flight". hypertextbook.com. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Pike, John. "Soyuz 26 and Soyuz 27". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Hollingham, Richard (December 21, 2015). "How the most expensive structure in the world was built". BBC.

- Giaimo, Cara (August 23, 2017). "Did 3 NASA Astronauts Really Hold a 'Space Strike' in 1973?". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

External links

- Mutiny in Space: Why These Skylab Astronauts Never Flew Again | Smart News | Smithsonian - Smithsonian Magazine.

- Living Aloft: Human Requirements for Extended Spaceflight, NASA SP-483, Chapter 8:Organization and Management—External Relations

- NASA The Skylab Crewed Missions