Snake Hill

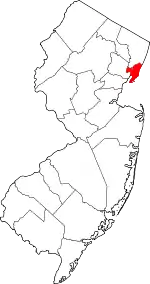

Snake Hill (known officially as Laurel Hill) is an igneous rock intrusion jutting up from the floor of the Meadowlands in southern Secaucus, New Jersey, at a bend in the Hackensack River.[1] It was largely obliterated in the 1960s by quarrying that reduced the height of some sections by one-quarter and the area of its base by four fifths.[2] The diabase rock was used as building material in growing areas like Jersey City. The remnant of the hill is the defining feature of Laurel Hill County Park. The high point, a 203-foot (62 m) graffiti-covered inselberg rock formation, is a familiar landmark to travelers on the New Jersey Turnpike's Eastern Spur, which skirts the hill's southern edge. The crest of the hill's unusual, sloping ridge is about 150 feet (46 m) high.

History

Snake Hill was formed by the same intrusion of magma that created the Palisades cliffs roughly 200 million years ago.

The Dutch colonists who originally settled the area called the high bluff 'Slangenbergh' ('Snakes Mountain' in English) because of the many snakes found there.[3] In 1658, Nicholas Varlet and Nicholas Bayard purchased Secaucus by Indian deed, which was confirmed by land patent in 1668. The entire 'plantation' was re-sold in 1676 to Edward Earle Jr., who sold a 50% interest to William Pinhorne. Three years later, Pinhorne and Earle divided the land into two separate plantations, with Pinhorne taking the roughly 1,200 acres called the 'Long Neck,' including Snake Hill.[4] Pinhorne lived there, naming the section containing his residence 'Mount Pinhorne'.[5][6]

From 1855 to 1962, there were Hudson County penal and charitable institutions on Snake Hill, which was essentially a self-contained city in which hundreds of people lived at any given time. The grounds had its own support facilities that included a sewer system, reservoir, electricity plant and incinerator. The on-site institutions included two almshouses, which provided shelter for the poor and elderly, a penitentiary, quarry and a number of medical facilities, all grouped on the north side of Snake Hill. The medical facilities included a Contagious Diseases Hospital, a Tuberculosis Sanatorium, and the Hudson County Lunatic Asylum, which existed from 1873 - 1939.[7][8]

When the Asylum opened, it had a capacity of 140 patients. Different wings were designated for men and women, and each room held several beds. People admitted to the Asylum were not restricted to the mentally ill, and whose conditions ranged from schizophrenia to syphilis, and according to a 2013 Union City Reporter article, many people were admitted to the hospital "who had no reason to be there: healthy residents who had been determined by their relatives to be a burden." Residents sometimes signed in their elderly relatives when they could no longer afford to take care of them. At the time, it was not difficult to sign in a patient, but harder for one to leave the hospital. According to Secaucus Town Historian Dan McDonough, "Anybody could sign somebody in. However, you would need three doctors to sign you out." The causes of death of many patients were not recorded, because the patients had been given pauper's funeral in the potter's field on the grounds, which is known as the Hudson County Burial Grounds.

In the 1930s, it adopted the name Mental Disease Hospital, as it was believed to be a less offensive name. At the end of that decade, the hospital was moved to County Avenue in Secaucus, at the location where Meadowview Psychiatric Hospital now exists. In 1939, the Mental Disease Hospital, which by then housed 1,872 people, ceased operations upon the opening of Meadowview Hospital. Patients were moved to the new hospital, at what is now the Meadowview Complex, in January 1927. They were transported in buses and ambulances, according to a contemporary Newark Evening News article. The Hudson County Hospital for Mental Diseases was renamed Hudson County Meadowview Hospital in 1967.

Quarrying took place from the late 19th century to the 1950s, when a section of the land was utilized as a prison quarry. Afterward, many of the properties were abandoned and had fallen into disrepair, and much of the hill had been leveled for the construction of sections of the New Jersey Turnpike. In 1962 Hudson County finished closing their facilities on the site, which included the county prison and the insane asylum. The County entered into a 20-year contract with Callanan Industries to level much of the hill. In the 1960s and 70's Gallo Asphalt had 4 asphalt plants, side by side, adjacent to the quarry and supplied paving materials throughout the surrounding urban region. Production ended on schedule in 1982. Ref:Refs.:

In 2003, more than 4,500 bodies of poor people, prisoners and patients were moved from the grounds to make way for the Turnpike's Exit 15X ramp, which would serve Secaucus Junction. When the graves were discovered, they were tested and found to have come from the facilities. Records of the mental hospital were also discovered. As of 2013, one of the old almshouses remains the only building still standing on the grounds.[7][8]

The name changed from Snake Hill to Laurel Hill in 1926, when Hudson County freeholder Katherine Whelan Brown[9] said that it was the "crowning Laurel of Hudson County" because of its prominence in the low lying meadowlands.[10][11] The high bluff has recently been called 'Fraternity Rock' (because of the greek letters painted on it presumably by local college fraternities), and 'Graffiti Rock'. The term 'Long Neck', originally used to describe the shape of the land between Pinhorne (now Penhorn) Creek and the Hackensack River, has been adapted to refer to the volcanic neck of the ridge.[10]

Laurel Hill County Park

Snake Hill and the area between it and the Hackensack River today comprise Laurel Hill County Park, part of the Hudson County Park System. In the early first decade of the 21st century, further blasting occurred along the New Jersey Turnpike. Most of the 184-acre (0.74 km2) parcel is currently being utilized as Laurel Hill County Park, which includes a portion of Hackensack RiverWalk.[12]

Laurel Hill Park is home to the Hackensack Riverkeeper's Field Office and Paddling Center, which is open weekends from April through October and weekdays by appointment. Hackensack Riverkeeper also conducts many of its Eco-Cruises from this park. There is a narrow Ridge Trail along the top of the hill.

Field Station: Dinosaurs

Field Station: Dinosaurs, an educational exhibit featuring animatronic dinosaurs utilizing the terrain to reflect the pre-historic era, opened here in May 2012.[13] The exhibit moved in the fall of 2015 to a new location in Bergen County.[14]

High Tech High School

High Tech High School (Previously located in North Bergen) built a new campus on the north side of the hill. The campus was first used for the 2018-2019 School Year.

Geology

The rock is a pipe-like diabase intrusive, which is believed to be an offshoot of the nearby Palisades Sill. Mineralized shales and sandstones, intruded by the diabase, are visible in the north and southwest sections of the property. Minerals were found in veins in both the diabase and metamorphosed sediments.

The mineral Petersite-(Y) was discovered at Snake Hill in June 1981 by Nicholas Facciolla, who took it to the Paterson Museum. In 1982 the mineral was recognized as a new discovery and named for Thomas A. Peters (1947-) and Joseph Peters (1951-), curators of minerals at the Paterson, New Jersey, museum and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, respectively.[15][16]

Culture

Snake Hill has had a modest, if largely anonymous, impact on the popular consciousness. A New York advertising executive, passing the hill on a train, is said to have drawn from it the inspiration for the Prudential "Rock of Gibraltar" logo in the 1890s.[17] Its rugged landscapes also feature prominently in artist Robert Smithson's 1968 work Untitled (6 Stops on a Section).[18]

References

- "Laurel Hill". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey., Variant name: Snake Hill

- Sullivan, Robert L. The Meadowlands: Wilderness Adventures at the Edge of a City. New York: Scribner, 1998.

- Long Island Historical Society, 1867, Memoirs, Volume 1, page 156.

- William Nelson. Genealogical Publishing Com, 1899, Patents and Deeds and Other Early Records of New Jersey, 1664-1703.

- Charles Hardenburg Winfield. Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, Printers, 1872, History of the Land Titles in Hudson County, N.J., 1609-1871, page 367.

- New Jersey Historical Society, 1901, Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, Volume 23.

- Jones, Richard Lezin (March 31, 2002). "Secaucus Journal; Humbled Mountain Offers a Mine of History, and Prehistory". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- Passantino, Joseph (October 20, 2013). "Creepy history of Snake Hill". The Union City Reporter. pp. 1 and 9.

- Gordon, Felice D. "After Winning: The Legacy of the New Jersey Suffragists, 1920-1947". New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

- "Small Wonders of Midgetville". Weird NJ. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- Quinn, John R. (1997). Fields of Sun and Grass. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 274.

- History of Snake Hill still as strange as can be Northjersey.com. August 30, 2012.

- Zernike, Kate (April 27, 2012), "Where Dinosaurs Roar Back", The New York Times, retrieved 2012-05-15

- "N.J. dinosaur park, saved from extinction, moves to Bergen County". NJ.com. April 3, 2016.

- "Petersite-(Y) Mineral Data". Mineralogy Database. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- Peacor, Donald R.; Dunn, Pete J. (182). "Petersite, a REE and phosphate analog of mixite". American Mineralogist, Volume 67, pp. 1039 - 1042.

- Quinn, John R. (1997). Fields of Sun and Grass. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 271.

- Graziani, Ron (April 5, 2004). Robert Smithson and the American Landscape. Cambridge University Press. p. 85. Google Books. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

Further reading

- Facciolla, N. (1981) Minerals of Laurel Hill, Secaucus, New Jersey.

- Manchester, J.G. (1931) The Minerals of New York City and Its Environs. New York Mineralogical Club Bulletin, 3:58-9.

- Peacor, D.R. & Dunn, P.J. (1982) American Mineralogist, 67:1039-42.

- Puffer, J. & Peters, J. (1974) Economic Geology. Magnetite Veins in Diabase of Laurel Hill, New Jersey, 69:1294-99.

- Tschernich, R. (1992) Zeolites of the World, 66, 116 p.