Snake oil

Snake oil is a euphemism for deceptive marketing, health care fraud, or a scam. Similarly, “snake oil salesman“ is a common expression used to describe someone who deceives people in order to get money from them.[1] The terms derive their meaning from the petroleum-based mineral oil or "snake oil" that used to be sold as a cure-all elixir for many kinds of physiological problems. Many 19th-century United States and 18th-century European entrepreneurs advertised and sold mineral oil (often mixed with various active and inactive household herbs, spices, drugs, and compounds, but containing no snake-derived substances whatsoever) as "snake oil liniment", making frivolous claims about its efficacy as a panacea. William Rockefeller Sr. sold petroleum-based "rock oil" as a cancer cure without the reference to snakes. Patent medicines that claimed to be a panacea were extremely common from the 18th century until the 20th, particularly among vendors masking addictive drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, alcohol and opium-based concoctions or elixirs, to be sold at medicine shows as medication or products promoting health.

History

Patent medicines originated in England, where a patent was granted to Richard Stoughton's elixir in 1712.[2] There were no federal regulations in the United States concerning the safety and effectiveness of drugs until the 1906 Food and Drugs Act.[3] Thus, the widespread marketing and availability of dubiously advertised patent medicines without known properties or origin persisted in the US for a much greater number of years than in Europe.

In 18th-century Europe, especially in the UK, viper oil had been commonly recommended for many afflictions, including the ones for which oil from the rattlesnake (pit viper), a type of viper native to America, was subsequently favored to treat rheumatism and skin diseases.[4] Though there are accounts of oil obtained from the fat of various vipers in the Western world, the claims of its effectiveness as a medicine have never been thoroughly examined, and its efficacy is unknown. It is also likely that much of the snake oil sold by Western entrepreneurs was illegitimate, and did not contain ingredients derived from any kind of snake. Snake oil in the United Kingdom and United States probably contained modified mineral oil.

In popular culture within the United States, snake oil is particularly renowned to be a commodity peddled at American Old West-themed medicine shows, although the judgment condemning snake oil as medicine took place in Rhode Island, and involved snake oil manufactured in Massachusetts.[5] The snake oil peddler is a stock character in Western movies, depicted as a traveling "doctor" with dubious credentials, selling fake medicines with boisterous marketing hype, often supported by pseudo-scientific evidence. To increase sales, an accomplice in the crowd (a shill) will often attest to the value of the product in an effort to provoke buying enthusiasm. The "doctor" will leave town before his customers realize they have been cheated. This practice has wide-ranging implications, and is known as a confidence trick, a type of fraud. This particular confidence trick is purported to have been a common mechanism utilized by peddlers in order to sell various counterfeit and generic medications at medicine shows.

From cure-all to quackery

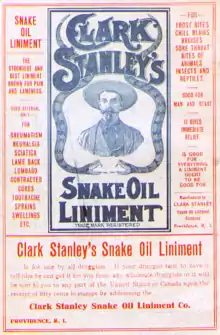

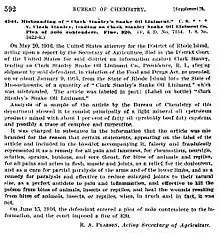

Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment – produced by Clark Stanley, the "Rattlesnake King" – was tested by the United States government's Bureau of Chemistry, the precursor to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA,) in 1916.[5] It was found to contain: mineral oil, 1% fatty oil (assumed to be tallow), capsaicin from chili peppers, turpentine, and camphor.[2]

In 1916, subsequent to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment was examined by the Bureau of Chemistry, and found to be drastically overpriced and of limited value. As a result, Stanley faced federal prosecution for peddling mineral oil in a fraudulent manner as snake oil. In his 1916 civil hearing instigated by federal prosecutors in the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island, Stanley pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to the allegations against him, giving no admission of guilt.[5] His plea was accepted, and as a result, he was fined $20[5] (about $470 in 2019).[6] The term snake oil has since been established in popular culture as a reference to any worthless concoction sold as medicine, and has been extended to describe a widely ranging degree of fraudulent goods, services, ideas, and activities such as worthless rhetoric in politics. By further extension, a snake oil salesman is commonly used in English to describe a quack, huckster, or charlatan.

Modern implications

False health products continue to be marketed during the 21st century using techniques formerly associated with snake oil. The marketing comprises storefronts, retail stores, and traveling peddlers; example products are herbalism, dietary supplements, or a Tibetan singing bowl (used for healing.) Claims that these products are scientific, healthy, or natural have no basis in science. Contrary to claims perpetuated by the Xinhua News Agency during the COVID-19 pandemic, the herbal product, Shuanghuanglian, does not prevent or treat infections from coronaviruses, yet its false claims of use against COVID-19 stimulated sales across the United States and China.[7][8]

See also

References

- . Cambridge Dictionary https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/snake-oil-salesman. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Nickell, J (1 December 1998). "Peddling Snake Oil; Investigative Files". Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 8 (4). Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "The Long Struggle for the Law". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Klauber, Laurence M. (1997). Rattlesnakes, vol II. University of California Press. p. 1050.

- Chemistry, United States Bureau of (1917). Service and Regulatory Announcements. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Palmer, James. "Chinese Media Is Selling Snake Oil to Fight the Wuhan Virus". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Phillips, James; Selzer, Jordan; Noll, Samantha; Alptunaer, Timur (31 March 2020). "Opinion : Covid-19 Has Closed Stores, but Snake Oil Is Still for Sale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020.

External links

| Look up snake oil in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Snake oil |

| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Snake oil |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snake oil. |

- Gandhi, Lakshmi (26 August 2013). "A History Of 'Snake Oil Salesmen'". Code Switch. National Public Radio. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Behn, A.R. (1909). Secret remedies, what they cost and what they contain, based on analyses made for the British Medical Association. British Medical Association. Retrieved 25 August 2020.