Snow goose

The snow goose (Anser caerulescens) is a species of goose native to North America. Both white and dark morphs exist, the latter often known as blue goose. Its name derives from the typically white plumage. The species was previously placed in the genus Chen, but is now typically included in the "gray goose" genus Anser.[2][3]

| Snow goose | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| White morph | |

| |

| Blue morph | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Anser |

| Species: | A. caerulescens |

| Binomial name | |

| Anser caerulescens | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

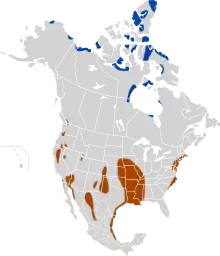

| Snow goose range: Breeding range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Snow geese breed north of the timberline in Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and the northeastern tip of Siberia, and spend winters in warm parts of North America from southwestern British Columbia through parts of the United States to Mexico.[4] Snow goose populations increased dramatically in the 20th century.

Taxonomy

The snow goose was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Anas caerulescens.[5][6] Linnaeus based his description on the "blue-winged goose" described in 1750 by the English naturalist George Edwards in his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. The specimen had been collected in Hudson Bay.[7] The snow goose is now placed in the genus Anser was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[8][9] The scientific name is from the Latin anser, "goose", and caerulescens, "bluish", derived from caeruleus, "dark blue".[10] The snow goose is the sister species to Ross's goose (Anser rossii).[11]

Two subspecies are recognised:[9][12]

- A. c. caerulescens (Linnaeus, 1758) – lesser snow goose - breeds in northeast Siberia, north Alaska and northwest Canada, winters in south USA, north Mexico and Japan

- A. c. atlanticus (Kennard, 1927) – greater snow goose – breeds in northeast Canada and northwest Greenland, winters in northeast USA

The greater snow goose is distinguished from the nominate form by being slightly larger. It nests farther north and east. The lesser snow goose can be found in two colour phases, the normal white-coloured animals and a dark grey-coloured 'blue' phase. The greater snow goose is rarely seen in a blue phase.[13]

Description

The snow goose has two color plumage morphs, white (snow) or gray/blue (blue), thus the common description as "snows" and "blues". White-morph birds are white except for black wing tips, but blue-morph geese have bluish-grey plumage replacing the white except on the head, neck and tail tip. The immature blue phase is drab or slate-gray with little to no white on the head, neck, or belly. Both snow and blue phases have rose-red feet and legs, and pink bills with black tomia ("cutting edges"), giving them a black "grin patch". The colors are not as bright on the feet, legs, and bill of immature birds. The head can be stained rusty-brown from minerals in the soil where they feed. They are very vocal and can often be heard from more than a mile away.

White- and blue-morph birds interbreed and the offspring may be of either morph. These two colors of geese were once thought to be separate species; since they interbreed and are found together throughout their ranges, they are now considered two color phases of the same species. The color phases are genetically controlled. The dark phase results from a single dominant gene and the white phase is homozygous recessive. When choosing a mate, young birds will most often select a mate that resembles their parents' coloring. If the birds were hatched into a mixed pair, they will mate with either color phase.

The species is divided into two subspecies on the basis of size and geography. Size overlap has caused some to question the division.[4] The smaller subspecies, the lesser snow goose (C. c. caerulescens), lives from central northern Canada to the Bering Straits area. The lesser snow goose stands 64 to 79 cm (25 to 31 in) tall and weighs 2.05 to 2.7 kg (4.5 to 6.0 lb). The larger subspecies, the greater snow goose (C. c. atlanticus), nests in northeastern Canada. It averages about 3.2 kg (7.1 lb) and 79 cm (31 in), but can weigh up to 4.5 kg (9.9 lb). The wingspan for both subspecies ranges from 135 to 165 cm (53 to 65 in).

Breeding

Long-term pair bonds are usually formed in the second year, although breeding does not usually start until the third year. Females are strongly philopatric, meaning they will return to the place they hatched to breed.

Snow geese often nest in colonies. Nesting usually begins at the end of May or during the first few days of June, depending on snow conditions. The female selects a nest site and builds the nest on an area of high ground. The nest is a shallow depression lined with plant material and may be reused from year to year. After the female lays the first of three to five eggs, she lines the nest with down. The female incubates for 22 to 25 days, and the young leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.

The young feed themselves, but are protected by both parents. After 42 to 50 days they can fly, but they remain with their family until they are two to three years old.

Where snow geese and Ross's geese breed together, as at La Pérouse, they hybridize at times, and hybrids are fertile. Rare hybrids with the greater white-fronted goose, Canada goose, and cackling goose have been observed.[4]

Migration

Snow geese breed from late May to mid-August, but they leave their nesting areas and spend more than half the year on their migration to-and-from warmer wintering areas. During spring migration (the reverse migration), large flocks of snow geese fly very high and migrate in large numbers along narrow corridors, more than 3,000 mi (4,800 km) from traditional wintering areas to the tundra.

The lesser snow goose travels through the Central Flyway, Mississippi Flyway, and Pacific Flyway across prairie and rich farmland to their wintering grounds on grassland and agricultural fields across the United States and Mexico, especially the Gulf coastal plain. The larger and less numerous greater snow goose travels through the Atlantic Flyway and winters on a relatively more restricted range on the Atlantic coastal plain. Traditionally, lesser snow geese wintered in coastal marsh areas where they used their short but strong bills to dig up the roots of marsh grasses for food. However, they have also since shifted inland towards agricultural areas, likely the cause behind the unsustainable population increase in the 20th century. This shift may help to contribute to increased goose survival rates, leading to overgrazing on tundra breeding grounds.[14]

In March 2015, 2,000 snow geese were killed in northern Idaho from an avian cholera epidemic while flying their spring migration to northern Canada.[15]

Vagrancy

Snow Goose is a rare vagrant to Europe but for a frequent escape from collections and an occasional feral breeder. Snow Geese are visitors to the British Isles where they are seen regularly among flocks of brant, barnacle goose, and greater white-fronted goose. There is also a feral population in Scotland from which many vagrant birds in Britain seem to derive.

In Central America, vagrants are frequently encountered during winter.[16]

Ecology

Outside of the nesting season, they usually feed in flocks. In winter, snow geese feed on left-over grain in fields. They migrate in large flocks, often visiting traditional stopover habitats in spectacular numbers. Snow geese frequently travel and feed alongside greater white-fronted geese; in contrast, the two tend to avoid travelling and feeding alongside Canada geese, which are often heavier birds.

The population of greater snow geese was in decline at the beginning of the 20th century, but has now recovered to sustainable levels. Snow geese in North America have increased to the point where the tundra breeding areas in the Arctic and the saltmarsh wintering grounds are both becoming severely degraded,[17] and this affects other species using the same habitat.

Major nest predators include Arctic foxes and skuas.[18] The biggest threat occurs during the first couple of weeks after the eggs are laid and then after hatching. The eggs and young chicks are vulnerable to these predators, but adults are generally safe. They have been seen nesting near snowy owl nests, which is likely a solution to predation. Their nesting success was much lower when snowy owls were absent, leading scientists to believe that the owls, since they are predatory, were capable of keeping competing predators away from the nests. A similar association as with the owls has been noted between geese and rough-legged hawks.[18] Additional predators at the nest have reportedly included wolves, coyotes and all three North American bear species.[19][20] Few predators regularly prey on snow geese outside of the nesting season, but bald eagles (as well as possibly golden eagles) will readily attack wintering geese.

Population

The breeding population of the lesser snow goose exceeds 5 million birds, an increase of more than 300% since the mid-1970s. The population is increasing at a rate of more than five percent per year. Non-breeding geese (juveniles or adults that fail to nest successfully) are not included in this estimate, so the total number of geese is likely higher. Lesser snow goose population indices are the highest they have been since population records have been kept, and evidence suggests that large breeding populations are spreading to previously untouched sections of the Hudson Bay coastline. The cause of this overpopulation may be the heavy conversion of land from forest and prairie to agricultural usage in the 20th century.

Since the late 1990s, efforts have been underway in the U.S. and Canada to reduce the North American population of lesser snow and Ross's geese to sustainable levels due to the documented destruction of tundra habitat in Hudson Bay and other nesting areas. The Light Goose Conservation Order was established in 1997 and federally mandated in 1999. Increasing hunter bag limits, extending the length of hunting seasons, and adding new hunting methods have all been successfully implemented, but have not reduced the overall population of Snow Geese in North America.[21][22]

Conservation Order for Light Geese

The late 1990s was when the mid-continent population of snow geese was recognized as causing significant damage to the arctic and sub-arctic breeding grounds which was also causing critical damage to other varieties of waterfowl species and other wildlife that uses the arctic and sub-arctic grounds for home habitat. The increase in population in substantial amounts raised concern to then DU chief biologist Dr. Bruce Batt who was part of a committee that put together various data and submitted it to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian Wildlife Service with the recommendation on ways to combat the growing population and the damage that the snow geese were creating in the arctic breeding grounds.

The committee recommended relaxing hunting restrictions and giving hunters a better opportunity to harvest more snow geese on their way back to the breeding grounds in the spring. The suggested restrictions were to allow the use of electronic callers, unplugged shotguns, extended shooting hours, and no bag limits. Two years after the Light Goose Conservation Order was introduced it was federally mandated in 1999.

Gallery

Anser caerulescens - MHNT

Anser caerulescens - MHNT A. c. atlanticus, spring migration, blue morphs in foreground, Alexandria, Ontario

A. c. atlanticus, spring migration, blue morphs in foreground, Alexandria, Ontario Wintering snow geese on Fir Island, Washington

Wintering snow geese on Fir Island, Washington Snow Goose landing

Snow Goose landing Snow geese in a corn field on Fir Island, Washington in the Skagit River delta

Snow geese in a corn field on Fir Island, Washington in the Skagit River delta Snow geese (Anser caerulescens)

Snow geese (Anser caerulescens)

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Anser caerulescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22679896A85973888. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22679896A85973888.en.

- Ogilvie, Malcolm A.; Young, Steve (2002). Wildfowl of the World. London: New Holland Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-84330-328-2.

- Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-19-861008-3.

- Mowbray, Thomas B.; Fred, Cooke; Barbara, Ganter (2000). "Snow Goose (Chen caerulescens)". In Poole, A. (ed.). The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 124.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 439.

- Edwards, George (1743). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Part 3. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 152, Plate 152.

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Division des Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 58, Vol. 6, p. 261.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Screamers, ducks, geese & swans". IOC World Bird List Version 10.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 48, 83. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Ottenburghs, J.; Megens, H.-J.; Kraus, R.H.S.; Madsen, O.; van Hooft, P.; van Wieren, S.E.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Ydenberg, R.C.; Groenen, M.A.M.; Prins, H.H.T. (2016). "A tree of geese: A phylogenomic perspective on the evolutionary history of True Geese". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 101: 303–313. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.05.021.

- Kenneth F. Abraham, Robert L. Jefferies (1997). Arctic Ecosystems in Peril: Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group. Part II High Goose Populations: causes, impacts and implications (PDF) (Report). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service. p. 1. Retrieved 15 November 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- McKelvey, Rick; Leafloor, Jim; Alisauskas, Ray (2010). "Lesser Snow Goose". Hinterland Who's Who. Canadian Wildlife Federation. ISBN 0-662-17199-3. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- "Light Goose Dilemma". www.ducks.org. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- http://www.cnn.com/2015/03/18/us/idaho-snow-geese-deaths/index.html

- Herrera, Néstor; Rivera, Roberto; Ibarra Portillo, Ricardo; Rodríguez, Wilfredo (2006). "Nuevos registros para la avifauna de El Salvador" [New records for the avifauna of El Salvador] (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Antioqueña de Ornitología (in Spanish and English). 16 (2): 1–19.

- "Snow geese degrade tundra". The New York Times. 22 September 2014.

- Tremblay, J.-P.; Gauthier, G.; Lepage, D.; Desrochers, A. (1997). "Factors Affecting Nesting Success in Greater Snow Geese: Effects of Habitat and Association with Snowy Owls". Wilson Bulletin. 109 (3): 449–461. JSTOR 4163840.

- Coakley, Amber (3 March 2009). "Duck Duck Goose – Snow Goose". Birders Lounge.

- Johnson, Stephen R.; Noel, Lynn E. (2005). "Temperature and Predation Effects on Abundance and Distribution of Lesser Snow Geese in the Sagavanirktok River Delta, Alaska". Waterbirds. 28 (3): 292. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2005)028[0292:TAPEOA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1524-4695. JSTOR 4132542.

- "Too Many Snow Geese | Central Flyways". central.flyways.us. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- "Light Goose Dilemma". www.ducks.org. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

Further reading

- Johnson, Mike (16 July 1997). "The snow goose population problem". Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anser caerulescens. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Anser caerulescens. |

- Conservation Order for Light Geese - Cornell Law School

- Snow Goose Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- The Nature Conservancy's Species profile: Snow Goose Learn more about the conservation of these geese

- Snow Goose - Chen caerulescens – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- "Snow Goose". Avibase.

- Song of the North Wind: A Story of the Snow Goose by Paul A. Johnsgard (1974, rev. 2009)

- "Snow goose media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Snow goose photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)