Soft-tissue sarcoma

A soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) is a malignant tumour, a type of cancer, that develops in soft tissue.[1] A soft tissue sarcoma is often a painless mass that grows slowly over months or years. They may be superficial or deep-seated. Any such unexplained mass will need to be diagnosed by biopsy.[2] Treatment may include, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted drug therapy.[3] The other type of sarcoma is a bone sarcoma.

| Soft-tissue sarcoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma in left lung of young child | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

There are many types. The World Health Organization lists more than fifty subtypes.[4][2]

Types

| Tissue of Origin | Type of Cancer | Usual Location in the Body |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrous tissue | Fibrosarcoma | Arms, legs, trunk |

| Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma | Legs | |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma | Trunk | |

| Fat | Liposarcoma | Arms, legs, trunk |

| Muscle |

Rhabdomyosarcoma Leiomyosarcoma |

Arms, legs Uterus, digestive tract |

| Blood vessels | Hemangiosarcoma | Arms, legs, trunk |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | Legs, trunk | |

| Lymph vessels | Lymphangiosarcoma | Arms |

| Synovial tissue (linings of joint cavities, tendon sheaths) |

Synovial sarcoma | Legs |

| Peripheral nerves | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour/Neurofibrosarcoma | Arms, legs, trunk |

| Cartilage and bone-forming tissue | Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma | Legs |

| Extraskeletal osteosarcoma | Legs, trunk (not involving the bone) |

| Tissue of Origin | Type of Cancer | Usual Location in the Body | Most common ages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | |||

| Striated muscle | Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||

| Embryonal | Head and neck, genitourinary tract | Infant–4 | |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Arms, legs, head, and neck | Infant–19 | |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyosarcoma | Trunk | 15–19 |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibrosarcoma | Arms and legs | 15–19 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma |

Legs | 15–19 | |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma | Trunk | 15–19 | |

| Fat | Liposarcoma | Arms and Legs | 15–19 |

| Blood vessels | Infantile hemangio-pericytoma | Arms, legs, trunk, head, and neck | Infant–4 |

| Synovial tissue (linings of joint cavities, tendon sheaths) |

Synovial sarcoma | Legs, arms, and trunk | 15–19 |

| Peripheral nerves | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (also called neurofibrosarcomas, malignant schwannomas, and neurogenic sarcomas) | Arms, legs, and trunk | 15–19 |

| Muscular nerves | Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Arms and legs | Infant–19 |

| Cartilage and bone-forming tissue | Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma | Legs | 10–14 |

| Extraskeletal mesenchymal | Legs | 10–14 |

An earlier version of this article was taken from the US National Cancer Center's Cancer Information Service.

Signs and symptoms

In their early stages, soft-tissue sarcomas usually do not cause symptoms. Because soft tissue is relatively elastic, tumors can grow rather large, pushing aside normal tissue, before they are felt or cause any problems. The first noticeable symptom is usually a painless lump or swelling. As the tumor grows, it may cause other symptoms, such as pain or soreness, as it presses against nearby nerves and muscles. If in the abdomen it can cause abdominal pains commonly mistaken for menstrual cramps, indigestion, or cause constipation.

Risk factors

Most soft-tissue sarcomas are not associated with any known risk factors or identifiable cause. There are some exceptions:

- Studies suggest that workers who are exposed to chlorophenols in wood preservatives and phenoxy herbicides may have an increased risk of developing soft-tissue sarcomas. An unusual percentage of patients with a rare blood vessel tumor, angiosarcoma of the liver, have been exposed to vinyl chloride in their work. This substance is used in the manufacture of certain plastics, notably PVC.[5]

- In the early 1900s, when scientists were just discovering the potential uses of radiation to treat disease, little was known about safe dosage levels and precise methods of delivery. At that time, radiation was used to treat a variety of noncancerous medical problems, including enlargement of the tonsils, adenoids, and thymus gland. Later, researchers found that high doses of radiation caused soft-tissue sarcomas in some patients. Because of this risk, radiation treatment for cancer is now planned to ensure that the maximum dosage of radiation is delivered to diseased tissue while surrounding healthy tissue is protected as much as possible.

- Kaposi's sarcoma, a rare cancer of the cells that line blood vessels in the skin and mucus membranes, is caused by human herpesvirus 8. Kaposi's sarcoma often occurs in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Kaposi's sarcoma, however, has different characteristics than typical soft-tissue sarcomas and is treated differently.

- In a very small fraction of cases, sarcoma may be related to a rare inherited genetic alteration of the p53 gene and is known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Certain other inherited diseases are associated with an increased risk of developing soft-tissue sarcomas. For example, people with neurofibromatosis type I (also called von Recklinghausen's disease, associated with alterations in the NF1 gene) are at an increased risk of developing soft-tissue sarcomas known as malignant peripheral nerve-sheath tumors. Patients with inherited retinoblastoma have alterations in the RB1 gene, a tumor-suppressor gene, and are likely to develop soft-tissue sarcomas as they mature into adulthood.

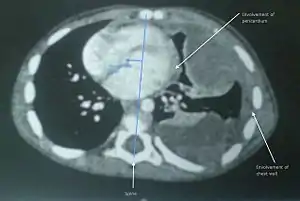

Diagnosis

The only reliable way to determine whether a soft-tissue tumour is benign or malignant is through a biopsy. The two methods for acquisition of tumour tissue for cytopathological analysis are:

- Needle aspiration biopsy, via needle

- Surgically, via an incision made into the tumour

A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope. If cancer is present, the pathologist can usually determine the type of cancer and its grade. Here, 'grade' refers to a scale used to represent concisely the predicted growth rate of the tumour and its tendency to spread, and this is determined by the degree to which the cancer cells appear abnormal when examined under a microscope. Low-grade sarcomas, although cancerous, are defined as those that are less likely to metastasise. High-grade sarcomas are defined as those more likely to spread to other parts of the body. For soft-tissue sarcoma, the two histological grading systems are the National Cancer Institute system and the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group system.[6][7][8]

Soft-tissue sarcomas commonly originate in the upper body, in the shoulder or upper chest. Some symptoms are uneven posture, pain in the trapezius muscle, and cervical inflexibility [difficulty in turning the head].

The most common site to which soft-tissue sarcoma spreads is the lungs.

Treatment

In general, treatment for soft-tissue sarcomas depends on the stage of the cancer. The stage of the sarcoma is based on the size and grade of the tumor, and whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body (metastasized). Treatment options for soft-tissue sarcomas include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted drug therapy.[3]

- Surgery is the most common treatment for soft-tissue sarcomas. The tumour is removed leaving a safe margin of surrounding healthy tissue to decrease the chances of its recurrence.

- Radiation therapy may be used as a neoadjuvant before surgery to shrink tumours, or as an adjuvant after surgery to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind. In some cases, it can be used to treat tumours that cannot be surgically removed.

- Chemotherapy may be used with radiation therapy either before or after surgery to try to shrink the tumor or kill any remaining cancer cells. There is evidence to suggest that doxorubicin chemotherapy as an adjuvant can reduce recurrence at the original site or elsewhere in the body.[9] Evidence also suggests chemotherapy can increase the length of time patients live, but this is less certain evidence. The use of chemotherapy to prevent the spread of soft-tissue sarcomas has not been proven to be effective. If the cancer has spread to other areas of the body, chemotherapy may be used to shrink tumors and reduce the pain and discomfort they cause, but is unlikely to eradicate the disease.

- A combination of docetaxel and gemcitabine could be an effective chemotherapy regimen in patients with advanced soft-tissue sarcoma.[10][11]

Research

The research in soft tissue sarcoma requires lot of effort because of its rarity and needs immense collaboration. In year 2019, few notable researches have been presented but mostly failed. However, we are learning that they can't be lumped together and each sarcoma is a different disease.[12]

Immunotherapy may have an upcoming role in treating soft tissue sarcomas like alveolar soft part sarcoma and pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma. In a report by Dr. Sameer Rastogi et al, a patient with advanced pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma had excellent response to combination of pembrolizumab and pazopanib.[13]

Epidemiology

Soft-tissue sarcomas are relatively uncommon cancers. They account for less than 1% of all new cancer cases each year. This may be because cells in soft tissue, in contrast to tissues that more commonly give rise to malignancies, are not continuously dividing cells.

In 2006, about 9,500 new cases were diagnosed in the United States.[14] Soft-tissue sarcomas are more commonly found in older patients (>50 years old), although in children and adolescents under age 20, certain histologies are common (rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma).

Around 3,300 people were diagnosed with soft-tissue sarcoma in the UK in 2011.[15]

Notable cases

- Actor Robert Urich died from synovial sarcoma.

- Actress Michelle Thomas died from desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor, a rare abdominal soft-tissue sarcoma.

- It Is Written evangelist Henry Feyerabend died from sarcoma in his leg.

- Video game concept artist Adam Adamowicz died from complications of a rare muscle sarcoma on Feb. 9, 2012. He was 43.

- Professional wrestler Jake Roberts revealed he has muscle cancer.

- Professional wrestler Zack Ryder revealed he suffered from synovial sarcoma as a teenager.[16]

- India's Ex Finance Minister Arun Jaitley died due to this disease on 24 August 2019.

- Writer Rachel Caine died from the disease on November 1 2020

References

- Ratan, R; Patel, SR (October 2016). "Chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma". Cancer. 122 (19): 2952–60. doi:10.1002/cncr.30191. PMID 27434055.

- Ferri, Fred (2019). Ferri's clinical advisor 2019 : 5 books in 1. Elsevier. p. 1219. ISBN 9780323530422.

- "Treating Soft Tissue Sarcomas". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Types of soft tissue sarcoma | Cancer Research UK". about-cancer.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Soft Tissue Sarcoma Risk Factors | CTCA". CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- Neuvill; et al. (2014). "Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: from histological to molecular assessment". Pathology. 46 (2): 113–20. doi:10.1097/PAT.0000000000000048. PMID 24378389. S2CID 13436450.

- Coindre JM (2006). "Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 130 (10): 1448–53. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2006)130[1448:GOSTSR]2.0.CO;2 (inactive 2021-01-16). PMID 17090186.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Grading of Bone & Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Tawil. 2016(inc details of French system)

- "Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000-10-23. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001419. ISSN 1465-1858.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-10. Retrieved 2010-06-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gemcitabine and Docetaxel in Metastatic Sarcoma: Past, Present, and Future. 2007(free full text)

- Rastogi, Sameer; Manasa, Parisa; Kalra, Kaushal; et al. (2019). "Advances in soft-tissue sarcoma – There are no mistakes, only lessons to learn!". South Asian Journal of Cancer. 8 (4): 258–259. doi:10.4103/sajc.sajc_215_19. PMC 6852635. PMID 31807494.

- Arora, Shalabh; Rastogi, Sameer; Shamim, Shamim Ahmed; Barwad, Adarsh; Sethi, Maansi (9 July 2020). "Good and sustained response to pembrolizumab and pazopanib in advanced undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: a case report". Clinical Sarcoma Research. 10 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s13569-020-00133-9. PMC 7346343. PMID 32670543.

- Ries LAG, Harkins D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2006.

- "Soft tissue sarcoma statistics". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- "The scars of the Superstars".

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |