South Pass Light

The South Pass Light, also known as the Port Eads Lighthouse[1][Note 1] South Point Light, or Gordon's Island Light, are a pair of lighthouses located on Gordon's Island at South Pass, in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana (USA), one of the primary entrances to the Mississippi River Delta from the Gulf of Mexico. The light station was established in 1831 and is still active.

South Pass Light, Port Eads, Louisiana, in 1945 | |

Location in Louisiana | |

| |

| Location | Plaquemines Parish |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°00′55″N 89°10′01″W |

| Year first constructed | 1832 (First) 1842 (Second) 1848 (Third) 1881 (Current) |

| Year first lit | 1881 (Current) |

| Automated | 1971 |

| Tower shape | skeletal tower with circular house at base |

| Markings / pattern | White with black lantern |

| Tower height | 35 metre |

| Focal height | 33 metre |

| Current lens | DCB-224 |

| Range | 14 nautical mile |

| Characteristic | Fl(5) W 60s |

History

In 1829, the U.S. Congress appropriated $40,000 for the construction for two lighthouse at South Pass and Southwest Pass, the two principal entrances to the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico. The South Pass light station as built in 1831 consisted of a wooden keeper's dwelling on top of which stood a wooden tower. The government's favored contractor for lighthouse construction at the time, Winslow Lewis, was given $19,150 to erect the structure and the lighthouse at South Pass. He equipped the lights with his patented lamps and reflectors then widely in use in American lighthouses; seven of the lamps and reflectors were located on either side of a revolving chandelier. He chose to build the South Pass Light on Gordon's Island, named after the New Orleans customs collector, Martin Gordon. It was Gordon who persuaded Lewis to abandon his original scheme of driving piles into the marshy ground to secure the foundation in favor of a floating foundation of a cross-hatched grid of squared timbers, a scheme that would ultimately prove fatal with the shifting silty ground below the foundation. Nonetheless, the first keeper, Henry Heistand, lit the lamps for the first time on 15 May 1832.[2]

During the first four decades of its existence the light station saw a number of incidents. In 1839, logs floating downriver knocked the keeper's dwelling off its pilings, and in 1841, the entire station was destroyed by a storm. The following year, 1842, its replacement, another wooden tower, arose on the opposite bank of the Mississippi, but within five years it had rotted beyond repair and in 1848 a third tower was completed. This tower, a wooden, octagonal structure, rose some fifty-four feet to a Cape-Cod-style round-domed lantern. Its base disappeared into the center of a dwelling with a steep roof fronted by a porch supported by six wooden columns, reminiscent of the French-Colonial plantation houses common to south Louisiana.[3][4]

The light at South Pass remained good for much of the subsequent decade: Lt. David Dixon Porter of the U.S. Navy in 1851 reported that it and its companion, the Southwest Pass Light, could be seen twelve miles away. Like most other southern lighthouses, its beacon was extinguished by Confederates at the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, but was restored the following year by Union forces, who installed a revolving third-order Fresnel lens in the tower, soon afterwards replaced by a fourth-order lens.[5]

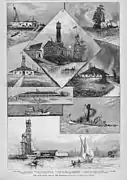

The lighthouse structure had deteriorated by 1867, and the Lighthouse Board, established in 1852, lobbied the U.S. Congress for money to build a new tower appropriate for a first-class seacoast light, since the beacon was often the first spotted by overseas navigational traffic from Europe and the West Indies. The need for the light's replacement was accelerated in 1876, when James Buchanan Eads began to introduce a wooden jetty system that deepened the river channels at the mouths of the Mississippi and ensured that the shipping lanes did not regularly silt up with sediment deposited from the river flowing downstream. The construction of these jetties received substantial coverage in the national press, including several large engravings of the work in Harper's Weekly. Upon their completion, the volume of trade at the Port of New Orleans doubled, while Eads received the honor of having the small settlement around the lighthouse named Port Eads after him.[6]

Finally, in 1879, Congress appropriated some $50,000 to construct a new tower at South Pass, which used the materials that were originally slated to be used for the Trinity Shoal Light in 1873 before the Lighthouse Board changed its mind and stationed a lightship at the latter location instead. The iron-skeleton tower, 105 feet tall and carrying a first-order Fresnel lens, was located 100 feet southeast of the old tower and first lit on 25 August 1881. In 1900, the tower was painted white with a black lantern so that ships could distinguish it better from its sister tower at Southwest Pass.[7][8][9]

The first-order lens was replaced by a DCB-224 optic beacon in 1951, and in 1971 the lighthouse was finally automated. The original first-order lens is now on display at the Louisiana State Museum in Baton Rouge.[10][11] The lighthouse was the sole structure at Port Eads to survive Hurricane Katrina in August 2005. Ultimately, the Federal government appropriated some $12 million to rebuild and enlarge the marina facilities at Port Eads, which now include docking and refueling premises, bunk rooms with an in-room bath for rent, weigh station, and a small restaurant.[12]

Design

The conical frame for the 1881 tower, consisting of eight inclined iron pillars, holds an elevated, cylindrical utility building pierced at the center by an iron tube that encloses the spiral staircase up to the lantern. Its design resembles many other seacoast towers along the Gulf Coast and Florida Straits (particularly the many offshore lighthouses along the Florida Keys) such as the Alligator Reef Light, American Shoal Light, Ship Shoal Light, Fowey Rocks Light, and Carysfort Reef Light. As at these other light stations, the iron skeleton frame at South Pass is reinforced by a web of many smaller iron braces that sturdily resist the wind from major storms and simultaneously allow the wind to pass through the structure. The massive lantern was sized as such to accommodate the huge first-order lens originally installed there.

Front range light

In 1886, a small beacon was placed on four wooden piles which established a front range light with the main South Pass Lighthouse acting as the rear.[13] Eventually a wooden tower was built in 1919 that also housed an air diaphone as well as the lens.[13] This structure was replaced in 1947 by a smaller skeletal iron tower (aka South Pass West Jetty Light). It is unknown when the front range was taken down by human or nature, but the jetty it was on has since disappeared into the sand. A small light on pilings now operates in the front light's former location.[10]

Gallery

South Pass Light as shown in Harper's Weekly, February 1884

South Pass Light as shown in Harper's Weekly, February 1884 South Pass Light and Port Eads in 1893

South Pass Light and Port Eads in 1893 Undated U.S. Coast Guard photo, post-1899, of South Pass Light

Undated U.S. Coast Guard photo, post-1899, of South Pass Light Undated photograph of the third (1848) South Pass Light tower

Undated photograph of the third (1848) South Pass Light tower An 1884 engraving, possibly from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, showing New Orleans-bound ships entering the Mississippi River channel at Port Eads. The newly completed South Pass light is visible on the right.

An 1884 engraving, possibly from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, showing New Orleans-bound ships entering the Mississippi River channel at Port Eads. The newly completed South Pass light is visible on the right.

References

- South Pass Range Lighthouses, also called the "Port Eads Lighthouse".

- Kraig Anderson, "South Pass, LA," LighthouseFriends.com, <http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=812>. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Vincent, Marie (1 February 1971). "Coast Guard Lighthouses". US Coast Guard Home. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Anderson, "South Pass, LA," retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Francis Ross Holland, Jr., America's Lighthouses: An Illustrated History (Brattleboro, VT: The Stephen Greene Press, 1972), 147.

- The Times-Picayune (2011). "1876:James Buchanan Eads saves the Port of New Orleans". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Vincent, for U.S. Coast Guard, ibid.

- Holland, Jr., ibid.

- LighthouseFriends.com (2011). "South Pass,La". LighthouseFriends.com. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- Rowlett, Russ. "Lighthouses of Louisiana". The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Vincent, for U.S. Coast Guard, ibid.

- Terri Sercovich (2010-09-28). "Work to begin on Port Eads Marina". The Plaquemines Gazette. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- "South Pass Lighthouse". Lighthouse Friends. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

Notes

- The Fyddeye Guide to America's Maritime History (2010 Fyddeye Media), pp.305-306; ISBN 978-0-615-38153-4

External links

- South Pass Light at Lighthouse Friends detailed history

- Tulane University lantern slide of South Pass Light, ca. 1925-40

- Sunset photo of South Pass Light

- Late afternoon view of South Pass Light

- Article on sport fishing at Port Eads with moonlit photo of South Pass Light

- US Lighthouse Society day photo of South Pass Light