Southern Railway (UK)

The Southern Railway (SR), sometimes shortened to 'Southern', was a British railway company established in the 1923 Grouping. It linked London with the Channel ports, South West England, South coast resorts and Kent. The railway was formed by the amalgamation of several smaller railway companies, the largest of which were the London & South Western Railway (LSWR), the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) and the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SE&CR). The construction of what was to become the Southern Railway began in 1838 with the opening of the London and Southampton Railway, which was renamed the London & South Western Railway.

Coat-of-arms of the Southern Railway | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| 1923 | Grouping; Southern Railway is created |

| 1929 | Phase one of electrification scheme complete |

| 1930 | Richard Maunsell's SR V "Schools" class introduced |

| 1937 | Oliver Bulleid becomes Chief Mechanical Engineer |

| 1941 | First SR Merchant Navy Class Pacific unveiled |

| 1948 | Nationalised |

| Constituent companies | |

| London, Brighton and South Coast Railway London & South Western Railway South Eastern and Chatham Railway See full List of constituent companies of the Southern Railway | |

| Successor organisation | |

| 1948 | Southern Region of British Railways |

| Key locations | |

| Headquarters | Waterloo station, London |

| Workshops | Ashford Brighton Eastleigh |

| Major stations | Waterloo station Victoria Charing Cross |

| Inherited route mileage | |

| 1923 | 2,186 miles (3,518 km) Mileage shown as at end of year stated. Source: Whitehouse, Patrick & Thomas, David St.John: SR 150, Introduction |

The railway was noted for its astute use of public relations and a coherent management structure headed by Sir Herbert Walker. At 2,186 miles (3,518 km), the Southern Railway was the smallest of the Big Four railway companies and, unlike the others, the majority of its revenue came from passenger traffic rather than freight. It created what was at that time the world's largest electrified main line railway system and the first electrified inter-city route (London—Brighton). There were two Chief Mechanical Engineers; Richard Maunsell between 1923 and 1937 and Oliver Bulleid from 1937 to 1948, both of whom designed new locomotives and rolling stock to replace much of that which was inherited in 1923. The Southern Railway played a vital role in the Second World War, embarking the British Expeditionary Force, during the Dunkirk operations, and supplying Operation Overlord in 1944; because the railway was primarily a passenger network, its success was an even more remarkable achievement.

The Southern Railway operated a number of famous named trains, including the Brighton Belle, the Bournemouth Belle, the Golden Arrow and the Night Ferry (London - Paris and Brussels). The West Country services were dominated by lucrative summer holiday traffic and included named trains such as the Atlantic Coast Express and the Devon Belle. The company's best-known livery was highly distinctive: locomotives and carriages were painted in a bright malachite green above plain black frames, with bold, bright yellow lettering. The Southern Railway was nationalised in 1948, becoming the Southern Region of British Railways.

History

Constituent companies and formation in 1923

Four important railway companies operated along the south coast of England prior to 1923 – the London & South Western Railway (LSWR), the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR), and the South Eastern Railway and the London Chatham and Dover Railway. (The last two had formed a working union known as the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SECR) in 1899.) These companies were amalgamated, together with several small independently operated lines and non-working companies, to form the Southern Railway in 1923, which operated 2186 route miles (3518 km) of railway. The new railway also partly owned several joint lines, notably the East London Railway, the West London Extension Joint Railway, the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway and the Weymouth and Portland Railway.

The first main line railway in southern England was the London and Southampton Railway, (renamed LSWR in 1838), which completed its line in May 1840.[2] It was quickly followed by the London and Brighton Railway (September 1841),[3] and the South Eastern Railway (formerly the South Eastern and Dover Railway) in February 1844.[4] The LSWR branched out to destinations including Portsmouth, Salisbury and later Exeter and Plymouth.[5] It grew to be the largest of the four constituent companies. The LBSCR was a smaller railway than its LSWR neighbour, serving the port of Newhaven and several popular holiday resorts on the south coast and operating much of the south London suburban network. It had been almost bankrupt in 1867, but, during the last twenty-five years of its existence, it had been well-managed and profitable.[6] It had begun to electrify routes around London (using an overhead line system) from 1909 to compete with the new electric trams that were taking away some of its traffic.[7] Finally, the SECR had been created after years of wasteful and damaging competition between the two companies involved, with duplication of routes and services. Both companies had been unpopular with the travelling public and operated poorly-maintained vehicles and infrastructure.[8] Nevertheless, real progress had been made in rectifying this. during the period 1899–1922.[9]

The formation of the Southern Railway was rooted in the outbreak of the First World War, when all British railway companies were taken into government control. Many members of staff joined the armed forces and it was not possible to build and maintain equipment at peacetime levels. After the war. the government considered permanent nationalisation. but instead decided on a compulsory amalgamation of the railways into four large groups through the 1921 Railways Act, known as the Grouping.[10] The resultant amalgamation of the four south coast railways to form the Southern Railway meant that several duplicate routes and management structures were inherited. The LSWR had most influence on the new company, although genuine attempts were made to integrate the services and staff after 1923.[11] The rationalisation of the system led to the downgrading of some routes in favour of more direct lines to the channel ports, and the creation of a co-ordinated, but not necessarily centralised form of management, based at the former LSWR headquarters in Waterloo station.[12]

In addition to its railway operations, the Southern Railway inherited several important port and harbour facilities along the south coast, including Southampton, Newhaven and Folkestone. It also ran services to the harbours at Portsmouth, Dover and Plymouth. These had come into being for handling ocean-going and cross-channel passenger traffic and the size of the railway-owned installations reflected the prosperity that the industry generated. This source of traffic, together with the density of population served in the London suburbs, ensured that the Southern would be a predominantly passenger-orientated railway.

Electrification

In 1923, the Southern Railway took over 24 1⁄2 route miles (39.4 km) of railway electrified with overhead line at 6.7 kV, 57 route miles (92 km) of railway electrified with a third rail at 660 V DC, and the 1 1⁄2-mile (2.4 km) long underground Waterloo & City Railway.[13] The route mileage of third rail electrification was to more than double in 1925 when the current was switched on on the routes to Guildford, Dorking and Effingham and the route from Victoria and Holborn Viaduct to Orpington via Herne Hill and the Catford Loop.[14] In 1926, electric trains started to run on the South Eastern Main Line route to Orpington and the three lines to Dartford using the 3rd rail system.[15] On 9 August 1926, the Southern announced that the DC system was to replace the AC system[16] and the last AC train ran on 29 September 1929.[17] Including the London Bridge to East Croydon route, electrified in 1928, by the end of 1929, the Southern operated over 277 1⁄2 route miles (446.6 km) of third rail electrified track and in that year ran 17.8 million electric train miles.[18]

One new electrified line was built, the Wimbledon and Sutton Railway, being opened in 1929/1930. Most of the area immediately south of London was converted, together with the long-distance lines to Brighton, Eastbourne, Hastings (via the LBSCR line), Guildford, Portsmouth and Reading, between 1931 and 1939.[19] This was one of the world's first modern mainline electrification schemes. On the former SECR routes, the lines to Sevenoaks and Maidstone were electrified by 1939. The routes to the Kent Coast were next in line for electrification and would have been followed by the electrification of the Southampton/Bournemouth route. The Second World War delayed these plans until the late 1950s and 1967 respectively. Although not in the Southern's original plans, electrification was extended from Bournemouth to Weymouth in 1988.

Economic crisis of the 1930s

The post-Wall Street Crash affected South Eastern England far less than other areas. The investment the company had already made in modernising the commuter network ensured that the Southern Railway remained in good financial health relative to the other railway companies despite the Depression. However, any available funds were devoted to electrification programme, and this marked the end of the first period under Chief Mechanical Engineer (CME) Richard Maunsell when the Southern Railway led the field in steam locomotive design. The lack of funds affected the development of new, standardised motive power, and it would take until the Second World War for the Southern Railway to take the initiative in steam locomotive design once again.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Southern Railway's proximity to the Channel ports meant that it became vital to the Allied war effort. Holidaymakers using the lines to the Channel ports and the West Country were replaced by troops and military supplies, especially with the threat of a German invasion of the south coast in 1940.[20] Before hostilities, 75% of traffic was passenger, compared with 25% freight; during the war roughly the same number of passengers was carried, but freight grew to 60% of total traffic. A desperate shortage of freight locomotives was remedied by CME Oliver Bulleid, who designed a fleet of 40 Q1 class locomotives to handle the high volumes of military traffic. The volume of military freight and soldiers moved by a primarily commuter and holidaymaker carrying railway was a breathtaking feat.

When the threat of invasion receded, the Southern Railway again became vital for the movement of troops and supplies preparing for the invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord.[20] This came at a cost, as the Southern Railway's location around London and the Channel ports meant that it was subjected to heavy bombing, whilst permanent way, locomotive, carriage and wagon maintenance was deferred until peacetime.[21]

Nationalisation

After a period of slow recovery in the late 1940s, the war-devastated company was nationalised along with the rest of the railway network in 1948 and incorporated into British Railways.[22] The Southern Railway retained a separate identity as the Southern Region of British Railways. The Southern Railway Company continued to exist as a legal entity until it went into voluntary liquidation on 10 June 1949, having satisfied the requirements of Sections 12, 13 and 24 of the Transport Act 1947 to ensure that all assets had been transferred to the British Transport Commission or otherwise properly distributed.[23][24][25] Many lines in London and Kent had been damaged during the war and much rolling stock was either damaged or in need of replacement. Just prior to nationalisation, the Southern Railway had started a vigorous renewal programme, and this was continued throughout the early 1950s.[26]

Revival in the privatised network

The former LBSCR routes to South London, Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire, from Victoria and London Bridge are now served by the current Southern. It was branded Southern on 30 May 2004, recalling the pre-nationalisation Southern Railway, with a green roundel logo with "Southern" written in yellow on a green bar. Southern is a subsidiary of Govia Thameslink Railway(GTR). GTR is a subsidiary of Govia, which is a joint venture between the British Go-Ahead Group (65%) and French company Keolis (35%).[27]

Accidents and incidents

- On 5 November 1926, a milk tank train became divided near Bramshott Halt, Hampshire. The train crew failed to inform the signalman or protect its rear in the belief that the issue could be resolved quickly. A passenger train was in a rear-end collision with it. One person was killed.[28]

- In March 1927, a train was derailed at Wrotham, Kent.[28]

- In August 1927, a passenger train was derailed at Bearsted, Kent.[28]

- On 24 August 1927, a passenger train was derailed at Sevenoaks, Kent due to a combination of the locomotive's design and the condition of the track. Thirteen people were killed and 21 were injured.[29]

- On 4 September 1934, two freight trains collided at Hither Green, London.[30]

- On 25 May 1933, a passenger train was derailed at Raynes Park, London, coming to rest foul of an adjacent line. Another passenger train was in a sidelong collision with it. Five people were killed and 35 were injured. The accident was caused by a failure to implement a speed restriction on a section of track that was under maintenance.[31]

- On 2 April 1937, an electric multiple unit crashed into the rear of another at Battersea Park, London due to a signalman's error. Ten people were killed and eighty were injured, seven seriously.[32]

- On 28 June 1937, a passenger train overran signals at Swanley Junction, Kent and was diverted into a siding where it crashed into an electricity substation. Four people were killed. The train was not booked to stop at Swanley, but arrangements had been made for it to do so. However, the driver of the train had not been informed of these arrangements.[31]

- In 1937, a boat train caught fire at Winchester, Hampshire due to an electrical fault in one of the carriages. Four carriages were destroyed.[33]

- On 14 August 1940, a passenger train was derailed at St. Denys, Hampshire due to enemy action. A bomb fell on the line in front of the train, which was unable to stop in time.[34]

- On 11 May 1941, Cannon Street station was bombed in a Luftwaffe air raid. At least one locomotive was severely damaged.[35]

- On 17 July 1946, a light engine collided with a passenger train at London Victoria station. Several people were injured.[28]

- In the summer of 1946, a freight train overran signals and was derailed by trap points at Wallers Ash, Hampshire.[34]

- On 21 January 1947, an empty stock train was in a rear-end collision with an electric multiple unit at South Bermondsey, London.[36]

- On 24 October 1947, an electric multiple unit train was in collision with another at South Croydon Junction, Surrey due to a signalman's error. In the deadliest accident to occur on the Southern Railway, 32 people were killed and 183 were injured.[37]

- On 26 November 1947, a passenger train was in a rear-end collision with another at Farnborough, Hampshire due to a signalman's error. Two people were killed.[31]

Geography

The Southern railway covered a large territory in south-west England including Weymouth, Plymouth, Salisbury and Exeter, where it was in competition with the Great Western Railway (GWR). To the east of this area it held a monopoly of rail services in the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. Above all, it had a monopoly of the London suburbs south of the River Thames, where it provided a complex network of secondary routes that intertwined between main lines.

Unlike the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway and the GWR, the Southern Railway was predominantly a passenger railway. Despite its small size it carried more than a quarter of Britain's passenger traffic because of its network of commuter lines around London, serving some of the most densely populated parts of the country. In addition, South London's geology was largely unsuitable for underground railways, meaning that the Southern Railway faced little competition from underground lines, encouraging a denser network stretching from stations located in close proximity to central London.

Key locations

The headquarters of the Southern was in the former LSWR offices at Waterloo station and there were six other London termini at Blackfriars, Cannon Street, Charing Cross, Holborn Viaduct, Victoria and London Bridge. The last of these also held the headquarters of the Eastern and Central Divisions. Other major terminal stations were at Dover, Brighton and Southampton. The railway also had one of Europe's busiest stations at Clapham Junction.

Locomotives were constructed and maintained at works inherited from constituent companies at Eastleigh, Ashford and Brighton. The largest was Eastleigh, which was built by the LSWR in 1909 to replace the cramped Nine Elms Locomotive Works in South London. Brighton had been constructing locomotives since 1852 for the LBSCR, and built 104 of 110 Bulleid Light Pacifics between 1945 and 1951. Ashford was inherited from the SECR, and had been built in 1847, and was the works that constructed half of the SR Q1 class. Ashford completed its final locomotive in March 1944, a War Department Stanier 8F 2-8-0 number 8764.

Carriage works had also been inherited at Eastleigh, and Lancing (which had been built in 1912 for the LBSCR). During the Second World War, both were turned over to wartime production such as Horsa and Hamilcar gliders. Wagon workshops were situated at Ashford and Eastleigh.

A concrete works near Exmouth Junction locomotive shed made platform seats, fencing and station lamp posts. A power station was at Durnsford Road Wimbledon.

Engineering

The South Western Main Line of the former LSWR between London and Southampton was completed by Joseph Locke with easy gradients, leading to several cuttings, tunnels and embankments across the Loddon, Test and Itchen Valleys, with brick arches constructed across South London to the site of Waterloo station. Such was the emphasis on minimising gradients that the stretch between Micheldever and Winchester has the longest constant gradient of any British main line.

The remainder of its area was traversed by three significant rows of hills: the North Downs, the Wealden Ridge and the South Downs. Thus Rastrick's Brighton Main Line of 1841, included one of the largest cuttings in the country at Merstham,[38] significant tunnels at Merstham, Balcombe, Clayton and Patcham as well as the famous Ouse Valley Viaduct. The major tunnels on the SECR network were at Merstham, Sevenoaks and Shakespeare Cliff.

Operations

The running of the Southern was undertaken by the Board of Directors, the first Chairman of which was Sir Hugh Drummond, appointed to the post in 1923. There were originally three general managers representing the interests of the three pre-Grouping railway companies: Sir Herbert Walker, Percy Tempest and William Forbes, although Walker was the sole occupant in the post within a year. The position of Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Southern Railway was given to a former employee of the SECR, Richard Maunsell. For ease of administration, the lines inherited in 1923 were divided into three geographical sections with a Traffic Department for each, loosely based upon the areas covered by the amalgamated companies:

- The Western Section (former LSWR routes) included the South Western Main Line, the Portsmouth Direct Line one quarter of the West Coastway Line (between Portsmouth and Southampton), and the West of England Main Line, both serving destinations popular with holidaymakers. It stretched into Devon and Cornwall as the line ran via Exeter, Okehampton and Plymouth, and this circuitous route was known derisively as the Southern Railway's "Withered Arm" because the GWR had a stronger presence in this region.

- The Central Section (former LB&SCR routes) included the Brighton Main Line (the most profitable and heavily used main line), the East Coastway Line, three quarters of the West Coastway Line, the Arun Valley Line and the Sutton & Mole Valley Lines.

- The Eastern Section (former SECR routes) included the South Eastern Main Line, the Chatham Main Line, the Hastings Line, the Kent Coast Line and the North Downs Line.

Operational and Commercial aspects of railway operation were brought under the control of Traffic Managers, relieving the General Manager of many tasks, allowing him to make policy decisions. Specialised Superintendents served under the Traffic Manager, breaking down the task of operating their respective sections. As such, the Southern Railway operated a hybrid system of centralised and decentralised management.

Passenger operations

- See also Named trains: UK

Passenger services, especially the intensive London suburban services, constituted the key breadwinner of the Southern Railway. The railway also served Channel ports and a number of attractive coastal destinations which provided the focus for media attention. This meant that the railway operated a number of famous named trains, providing another source of publicity for John Elliot. The Eastern and Central Sections of the network served popular seaside resorts such as Brighton, Eastbourne, Hastings and the Channel ports, whilst the Western Section catered for the heavy summer holiday traffic to the West Country resorts. Passenger services on the Southern Railway consisted of luxury Pullman dining trains and normal passenger services, which gave the railway a high total number of carriages at 10,800.

Pullman services

Pullman services were the premier trains of the Southern, reflecting the pride felt towards the railway. These luxury services included several boat trains such as the Golden Arrow (London-Paris, translated as Flèche d'Or for the French part of its route), The Cunarder (London - Southampton Ocean Liner service) and the Night Ferry (London - Paris and Brussels), the Brighton Belle on the Central Section, and the Bournemouth Belle and Devon Belle on the Western Section.

The Golden Arrow was the best-known train of the Southern Railway, and was introduced on 15 May 1929. The train consisted of Pullmans and luggage vans, linking London Victoria to Dover, with transfer to the French equivalent at Calais. The Brighton Belle, which had its origins in 1881 with the 'Pullman Limited' of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, which renamed the service the 'Southern Belle' in 1908. The train was steam-hauled until 1933 when electric units were introduced after the electrification of the London-Brighton main line. On 29 June 1934 the train was renamed the Brighton Belle and continued until withdrawal in 1972.

The SECR had introduced a Pullman train called the "Thanet Pullman Limited" from Victoria to Margate in 1921. The service was not a success and ceased to run in 1928. The service was however re-introduced by British Railways as the Thanet Belle in 1948.[39]

Titled trains

Amongst the ordinary services, the Southern Railway also operated famous titled express trains such as the Atlantic Coast Express ("ACE"). With a large variety of holiday destinations including Bude, Exmouth, Ilfracombe, Padstow, Plymouth, Seaton, Sidmouth and Torrington, the 11am "ACE" from Waterloo, as the Atlantic Coast Express became known, was the most multi-portioned train in the UK from its introduction in 1926. This was due to sections of the train splitting at selected junctions for onward journey to their final destinations in the West Country. Padstow railway station in Cornwall was the westernmost point of the Southern Railway, and marked the end or beginning of the "ACE", which was the longest timetabled journey on the network.

The importance of the destination dictated the motive power selected to haul each portion to their final destinations. Through carriages to East Devon and North Cornwall were invariably hauled by diminutive Drummond M7 tank locomotives, and from 1952, BR Standard Class 3 2-6-2T's; the rest of the train continued behind a Bulleid Light Pacific to Plymouth. The final "ACE" was hauled on 5 September 1964 when the Western Section of the former Southern Railway network was absorbed into the Western Region of British Railways.

Commuter services

Inner London suburban services were fully electrified by 1929 and worked by electric multiple units of varying lengths according to demand, which had the advantage of rapid acceleration and braking. The railway then began a successful programme to electrify its most heavily used main lines, building up a substantial commuter traffic from towns such as Guildford, Brighton and Eastbourne.

Other passenger services

The remainder of passenger operations were non-Pullman, reflecting the ordinary business of running a passenger railway. West Country services were dominated by lucrative summer holiday traffic and passengers wishing to travel to the Isle of Wight and further afield. In winter months, the western extremity of the Southern Railway network saw very little local use, as the railway served sparsely populated communities. Competition with the GWR also diluted passenger traffic within this area, as this carried the bulk of passengers to the major urban centres of the West Country. Steam-hauled passenger services in the east of the network were gradually replaced with electric traction, especially around London's suburbs.[40]

Passenger services on secondary routes were given motive power that befitted the lacklustre nature of the duty, with elderly locomotives used to provide a local service that fed into the major mainline stations such as Basingstoke. The use of elderly locomotives and stock was invariably a financial consideration, intended to prolong the life of locomotives that would otherwise be scrapped. In some cases, the route was such that some of the newer classes were precluded from operating because of restrictions in loading gauge, the Lyme Regis branch from Axminster providing an example.

The Southern Railway also operated push-pull trains of up to two carriages in commuter areas. Push-pull operations did not need the time-consuming use of a turntable or run-around at the end of a suburban branch line, and enabled the driver to use a cab in the end coach to drive the locomotive in reverse. Such operations were similar to the autotrains, with a Drummond M7 providing the motive power.

Freight operations

Passenger traffic was the main source of revenue for the Southern Railway throughout its existence, although goods were also carried in separate trains. Goods such as milk and cattle from the agricultural areas of the West Country provided a regular source of freight traffic, whilst imports from the south coast ports also required carriage by rail to freight terminals such as the large Bricklayers Arms facility. The railway operated three large marshalling yards for freight on the outskirts of South London, at Feltham, Norwood and Hither Green, where freight could be sorted for onward travel to their final destinations. It also handled a large volume of cross-London freight from these to other yards north of the river via the West London and East London Lines which were jointly owned by the Southern Railway.

As locomotives increased in size so did the length of goods trains from 40 to as many as 100 four-wheeled wagons, although the gradient of the line and the braking capabilities of the locomotive often limited this. The vacuum brake, which was standard equipment on passenger trains, was gradually fitted to a number of ordinary goods wagons, allowing a number of vacuum "fitted" trains to run faster than 40 mph (64 km/h). While typical goods wagons could carry 8, 10 or (later) 12 tons, the load placed into a wagon could be as little as 1 ton, as the railway was designated as a common carrier that could not choose what goods it could carry.

Ancillary operations

The Southern Railway inherited a range of railway-related activities from its constituent companies, which it continued to develop until nationalisation in 1948. These activities included several ports, a fleet of ships, road services (both freight and passenger) and several hotels. These ancillary operations provided extra revenue for the railway at a time when railways were classified as a common carrier by the Railways Act of 1844, and could not compete with road with regards to pricing. This was because railways were obliged to advertise their rates of carriage at railway stations, which could subsequently be undercut by road haulage companies. The Southern Railway also invested in an air service during the 1930s, which supplemented the popular sea crossings to the Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands.

Shipping

The Southern inherited docks at Southampton, Newhaven, Plymouth, Folkestone, Dover, Littlehampton, Whitstable, Strood, Rye, Queenborough, Port Victoria and Padstow. The Southern continued to invest heavily in these facilities, and Southampton overtook Liverpool as Britain's main port for Trans-Atlantic liners. The Southern inherited 38 large turbine or other steamers and a number of other vessels branded under Channel Packet, the maritime arm of the railway, all of which passed to British Railways control after nationalisation in 1948.

Ships

.jpg.webp)

The Southern inherited a number of ships from its constituent companies, some of which were converted to car ferries when this mode of transport became more common. Such conversions were needed on the French routes, where holidays by car were beginning to become popular. Services to the Channel Islands began in 1924, along with services to Brittany in 1933 and finally Normandy commencing just prior to nationalisation in 1947.[41]

- ex-LSWR ships

SS Alberta, SS Ardena, SS Brittany, SS Caesarea, SS Cherbourg, SS Hantonia, SS Laura, SS Lorina, SS Normannia, SS Princess Ena, SS Vera.[41]

- ex-LBSC ships

SS Arundel, SS Brighton, SS Dieppe, SS La France, SS Newhaven, SS Paris, SS Rouen, SS Versailles.[42]

- ex-SECR ships

SS Biarritz, SS Canterbury, SS Empress,SS Engadine, SS Invicta, SS Maid of Orleans, SS Riviera, SS Victoria.[43]

- ex-LBSC/LSWR joint ships

PS Duchess of Albany, PS Duchess of Kent, PS Duchess of Fife, PS Duchess of Norfolk, PS Princess Margaret.[44]

- Ships built for the SR

SS Arromanches, SS Autocarrier, SS Brighton, SS Brittany, TSS Canterbury, SS Deal, SS Dinard, SS Falaise, SS Fratton, PS Freshwater, SS Hampton Ferry, SS Haslemere, SS Hythe, SS Invicta, SS Isle of Guernsey, SS Isle of Jersey, SS Isle of Sark, SS Isle of Thanet, SS Londres, SS Maid of Kent, SS Maidstone, PS Merstone, SS Minster, PS Portsdown, SS Ringwood, PS Ryde, PS Sandown, SS Shepperton Ferry, PS Shanklin, PS Southsea, SS St Briac, SS Tonbridge, SS Twickenham Ferry, SS Worthing, PS Whippingham, SS Whitstable.[45][46][47][48][49]

- Ships managed by SR

During the Second World War and afterwards, Southern managed a number of ships for the Ministry of War Transport.

Hotels, road transport and air transport

Ten large hotels were owned by the company, at the London termini and at the coast. The Charing Cross Hotel, designed by Edward Middleton Barry, opened on 15 May 1865 and gave the station an ornate frontage in the French Renaissance style. At Cannon Street station in London, an Italianate style hotel was constructed in 1867, designed by Barry.[50] This provided much of the station's passenger facilities as well as an impressive architectural frontispiece to the street prior to demolition in 1960. London Bridge station boasted The Terminus hotel of 1861, which was turned into offices for the LBSCR in 1892, and destroyed by bombing in 1941.[51] Victoria station had the 300-bedroom Grosvenor hotel, which was rebuilt in 1908. Other hotels were to be found at Southampton and other port locations connected to the railway.

From 1929, the Southern Railway invested in bus companies providing feeder services to its trains. The brand names Southern National (a joint venture with the National Omnibus & Transport Co. Ltd.) and Southern Vectis have long outlived the railway company they originally served.[52] The Southern Railway also undertook freight transfer by road, owning a fleet of goods vehicles providing a door-to-door delivery service. This was especially useful for bulky items that required delivery to areas not immediately served by a railway. Conflat-type wagons were used to carry containers by rail to a destination close to the delivery address, where they would be transferred by crane onto the trailer of a vehicle for onward travel by road.

In conjunction with other Big Four companies the Southern Railway also invested in providing air services for passengers, notably to the Channel Islands and Isle of Wight, which complemented the shipping operations. Such operations provided the chance to take revenue from non-railway passengers, and enabled fast air-freight services between the islands and the mainland. However, this operation was disrupted during the Second World War due to the occupation of the Channel Islands, and the rationing of aviation fuel.

In 1937, the Southern Railway was involved in a scheme to build a new airport at Lullingstone, Kent, holding an option to purchase the land that the airport was to be built on.[53] Parliamentary approval was obtained to construct a short branch line from Lullingstone station to the airport.[54] At their 1938 Annual General Meeting, it was stated that the opinion of the company was that the cost of building the airport meant that there would not be sufficient return to justify the expenditure.[55] The option to purchase the land subsequently lapsed.[53]

Livery, traction and rolling stock

Livery and numbering system

For most of its existence the Southern Railway painted its 2,390 locomotives in a rich yellow/brown Olive green, with plain black frames and wheels, and fittings were lined in black with thin white edges. From 1937, the basic livery was changed by Bulleid to a matt blue/green Malachite green that was similar in appearance to copper carbonate. This was complemented with black wheels and frames with bright yellow lettering and lining-out of the various locomotive fixtures. Some of Bulleid's locomotives had their wheels painted in Malachite green with yellow rims, though this combination was scarcely used. Pre-grouping and Maunsell locomotives were given yellow and black lining to complement the Malachite green livery. During the Second World War, engines that went for overhaul were painted in an overall matt black due to the scarcity of paint and labour. The yellow lettering remained, highlighted with Malachite green. The period leading up to nationalisation in 1948 saw a reversion to Malachite green, albeit in gloss form. Below are examples of Southern Railway livery, including the approximate dates of first application:

- Gloss black (common to most freight designs at grouping, adopted by Maunsell as standard in 1923)

- LBSCR dark umber (1905–1923)

- LSWR Urie sage green (1912–1924; this became the standard passenger locomotive livery immediately after grouping)

- LSWR holly green (1912–1923; freight livery inherited from the LSWR at grouping)

- SECR grey (until 1923; inherited from the SECR at grouping)

- SR Maunsell olive green (1924–1939; introduced as the first standard passenger livery for the Southern Railway)

- Wartime matt black (1940–1950; a wartime labour-saving livery)

- SR Bulleid light green (1938–1940; first applied to N15 and H15 classes, dropped in favour of malachite green)

- SR Bulleid malachite green (1939–1950; became standard livery for all Southern passenger locomotives)

Maunsell locomotives featured name and number plates of polished brass with a red or black background in 1924. Bulleid nameplates were generally gunmetal with polished brass lettering, and featured crests depicting aspects of the class theme (Merchant Navy, West Country or Battle of Britain).

Until 1931 the Southern Railway initially maintained the locomotive numbers from its constituents, and solved the problem of more than one locomotive having the same number by letter prefixes denoting the main works of the former owning company. All ex-SECR locos were prefixed by "A" (for Ashford), ex-LBSCR by "B" (for Brighton) and ex-LSWR engines by "E" (for Eastleigh). Isle of Wight locomotive numbers were prefixed by "W" (for Wight). New locomotives were prefixed by the letter of the works where they were built. In 1931 the fleet was re-numbered by dropping all prefixes, leaving E-prefixed numbers unchanged, adding 1000 to A-prefixed numbers and 2000 to B-prefixed ones, an exception being the Z-class 0-8-0 shunters whose numbers A950-A957 only lost the prefix, with no addition.[56] (Some non-revenue-earning locos were exempt from this scheme).

Under Bulleid, a new continental system of numbering was introduced for his own locomotives, based upon his experiences at the French branch of Westinghouse Electric before the First World War, and his tenure in the rail operating department during that conflict. The Southern Railway number adapted a modified UIC classification system where "2" and "1" refer to the number of un-powered leading and trailing axles respectively, and "C" refers to three driving axles (the system was only applied to new 6-coupled locos and one Co-Co electric loco before nationalisation). As an example, the first Merchant Navy class locomotive was numbered 21C1.[57]

Motive power

The Southern Railway inherited in the region of 2,281 steam locomotives from its constituent companies at grouping[58] The railway handed over in the region of 1789 locomotives to British Railways in 1948.[59] Similarly, it inherited 84 DC multiple units (later designated 3-SUB) from the LSWR and 38 AC units (later designated CP and SL classes) from the LBSCR, and handed over in the region of 1480 DC units.

Steam Locomotives

From 1924 Maunsell began standardising the fleet of locomotives for ease of maintenance. Later Bulleid undertook sweeping changes that propelled the Southern Railway into the forefront of locomotive design.

The first locomotives constructed for the Southern Railway were to designs inherited from the pre-Grouping railway companies, such as the N15 class and H15 class, though both were modified by Maunsell from the original design.[60] These were intended as interim solutions to motive power problems, since several designs in operation on the Southern Railway were obsolete. The 1920s was the era of standardisation, with ease of maintenance and repair key considerations in a successful locomotive design.[61]

In 1926, the first of new Southern Railway designed and built locomotives emerged from Eastleigh works, the Maunsell Lord Nelson class, reputedly the most powerful 4-6-0 in Britain at the time.[62] So successful was the Lord Nelson class that the Royal Scot class had its origins in the Maunsell design.[63] However, the Depression of 1929 precluded further improvements in Southern Railway locomotive technology, apart from the V "Schools" class 4-4-0 and various electric designs.[64] Maunsell also designed locomotives for use in freight yards such as that at Feltham in south west London, the final example of which was the Q class. The design of the Q class coincided with Maunsell's ill health, resulting in a conservative approach to design. The first examples were completed in 1937, the year in which Maunsell retired from the CME's position.

Maunsell was succeeded in 1937 by Oliver Vaughan Snell Bulleid, who brought experience gained under Sir Nigel Gresley at the LNER. He designed the Bulleid chain-driven valve gear that was compact enough to fit within the restrictions of his Pacific designs, the Merchant Navy class of 1941 and the Light Pacific design of 1945. Ever the innovator, Bulleid introduced welded steel boilers and steel fireboxes which were easier to repair than the copper variety, whilst a new emphasis on cab ergonomics was followed.[65] Established locomotive design practices were altered in his designs, with the wheels changed from the traditional spoked to his BFB disc wheel design, giving better all-round support to the tyre.[66]

Visually, the most unusual of his designs was a small, heavy freight locomotive, the most powerful and last non-derivative design of 0-6-0 to operate in Britain.[64] This Q1 class eliminated anything that might be considered unnecessary in locomotive design, including the traditional wheel splashers.[67] With innovative lagging material that dictated the shape of the boiler cladding, the Q1 was regarded by many as one of the ugliest locomotives ever constructed.[68] The 40 engines produced required the same amount of material needed for 38 more conventional machines, justifying the economies and design.[69]

Bulleid's innovation stemmed from a belief in the continued development of steam traction, and culminated in the Leader class of 1946, an 0-6-6-0 design that had two cabs, negating the use of a turntable.[70] The entire locomotive was placed on two bogies, enabling negotiation around tight curves, while the slab-sided body could be cleaned by a labour-saving carriage washer.[71]

Despite the successes of the Pacifics and the unusual 0-6-0 Q1 freight locomotives, the Pacifics were difficult to maintain and featured enough eccentricities to justify rebuilding in the mid-1950s. The innovations ensured that the Southern was once again leading the field in locomotive design, and earned Bulleid the title "last giant of steam" in Britain.[72]

Diesel locomotives

Maunsell began experimenting with the use of diesel locomotives for yard shunting in 1937. He ordered three locomotives, which proved to be successful, but his retirement and the onset of the Second World War prevented further development. Bulleid adapted and improved the design but his class did not appear until 1949, after nationalisation. Bulleid also designed a class of main line diesel-electric locomotives, continuing to push back the boundaries of contemporary locomotive design and established practice,[73] but this was built by British Railways.

Electric locomotives

The Southern Railway also built two mixed-traffic electric locomotives, numbered CC1 and CC2 under Bulleid's numbering system. They were designed by Bulleid and Alfred Raworth, and were renumbered 20001 and 20002 after nationalisation. At this time a third locomotive was under construction, and was numbered 20003 in 1948.[74] The locomotives were later classified as British Rail Class 70. These incorporated a cab design similar to that of the 2HAL (2-car Half Lavatory electric stock) design constructed from 1938. This was due to ease of construction by welding, which allowed both cheap and speedy construction. With the outbreak of war in 1939, most new locomotive construction projects were put on hold in favour of the war effort, although construction of CC1 and CC2 was exempted from this because of promised savings in labour and fuel over steam locomotives.[75]

Electric Multiple Units (EMUs)

The early LBSCR AC overhead Electric multiple units (EMU) were phased-out by September 1929 and converted into DC types.[76] All further electrification was at 660 V DC, and investment was made in modernising the fleet inherited from the pre-Grouping companies, and building new stock often by converting existing steam hauled carriages. The Southern Railway's EMU classification meant the unit type was given a three-letter code (sometimes two letters), prefixed by the number of carriages within each unit. These early suburban units, constructed between 1925 and 1937 were therefore designated 3-SUB, or later 4-SUB, depending on the number of coaches. The EMUs consisted of a fixed formation of two driving units at both ends of the train, and could have varying numbers of carriages in between (as indicated in the classification).

Newly built units of 4-LAV 6PUL and 5BEL (Brighton Belle) types were introduced in 1932 for the electrification of the Brighton main line. Further types were introduced as electrification spread further. Thus the 2-BIL units were constructed between 1935 and 1938 to work long-distance semi-fast services to Eastbourne, Portsmouth and Reading, or the 2-HAL for those to Maidstone and Gillingham. 4-COR units, handled fast trains on the London Waterloo railway station to Portsmouth Harbour railway station from April 1937.

A total of 460 electric vehicles were to be built by the Southern Railway before nationalisation.[77] Variants of the Southern Railway's electric stock included Pullman carriages or wagons for the carriage of parcels and newspapers, allowing flexibility of use on the London suburban lines and the Eastern Section of the network.[40]

Other forms of traction

The railway also experimented with other forms of traction. It bought a 50 hp petrol-driven Drewry Railcar in 1927 to test its operating cost and reliability on lightly used branch lines. It was not successful and was sold to the Weston, Clevedon and Portishead Railway in 1934.[78] Similarly, a Sentinel steam railcar was purchased in 1933 for use on the Devil's Dyke branch. It was transferred from that line in March 1936 and tried in other areas, but was withdrawn in 1940.[79]

Carriages

.JPG.webp)

The Southern inherited many wooden-bodied carriage designs from its constituent companies. However, there was an emphasis on standardising the coaching stock, which led to Maunsell designing new carriages. These were classified between 0 and 4, so that an 8' 0¾" wide carriage was "Restriction 0".[80] The restrictions related to the Southern's composite loading gauge, so that some more restricted routes could be catered for. The new carriages were based upon the former LSWR "Ironclad" carriage designs, and comprised First and Third Class compartments, each of which contained a corridor and doors for each compartment, enabling quick egress on commuter services.[77] Similar principles were applied to the electric train sets, where quick passenger egress promoted a punctual service.

The Southern Railway was one of the few railways to marshal its carriages into fixed numbered sets.[81] This made maintenance easier, as the location of a particular set would always be known through its number, which was painted on the ends of the set. A pool of "loose" carriages was kept for train strengthening on summer Saturdays and to replace faulty stock.[81]

The second phase of carriage construction began towards the end of the Southern Railway's existence. Bulleid had vast experience in carriage design from his time with the LNER, and he applied this acquired knowledge to a new fleet of well-regarded carriages (see picture).[74] One of his more unusual projects was his "Tavern Car" design, carriages that were to represent a typical country tavern, with a bar and seating space provided within the carriage. The outside of the "Tavern Cars" were partially painted in a mock-Tudor style of architecture, and were given typical public house names. Poor ventilation from small windows made the "Tavern Cars" unpopular amongst the travelling public, with several being converted to ordinary use during the 1950s.[74]

The Southern Railway was the only one of the "Big Four" British railway companies that did not operate sleeping cars other than those brought in from the continent on the 'Night Ferry'. This was because the short distances meant that such provision was not financially viable.[77] The Southern Railway also undertook the practice of converting inherited carriages into electric stock, a cheaper alternative to constructing brand new EMUs. Bulleid initiated an unusual project that attempted to address the problem of overcrowding on suburban services. The answer to the problem was Britain's first double-deck carriages, which were eventually built in 1949. Two sets of four cars were completed and saw use until the 1970s, powered by electric in the same way as the EMUS.[82] However, further orders for these trains were not placed due to cramped conditions inside which were dictated by the restrictions of the loading gauge.[74]

Wagons

The Southern Railway painted its freight wagons dark brown. Most wagons were four-wheeled with the letters "SR" in white, and there were also some six-wheeled milk tankers on the South Western Main Line which supplied United Dairies in London.[83] As the railway was primarily passenger-orientated, there was little investment in freight wagons except for general utility vans, which could be used for both freight and luggage. These consisted of bogie and four-wheel designs, and were frequently used on boat trains. At its peak the Southern Railway owned 37,500 freight wagons; in contrast, the Railway Executive Committee controlled 500,000 privately owned colliery wagons during the Second World War.

Cultural impact

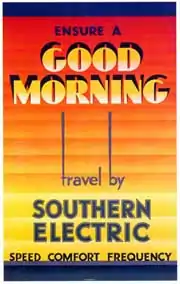

The Southern Railway was particularly successful at promoting itself to the public. The downgrading of the Mid-Sussex line via Horsham that served Portsmouth was met with hostility by the general public, causing a public relations disaster.[85] This stimulated the creation of the first "modern" public relations department with the appointment of John Elliot (later Sir John Elliot) in 1925. Elliot was instrumental in creating the positive image that the Southern enjoyed prior to the Second World War, building a publicity campaign for its electrification project that marketed the "World's Greatest Suburban Electric".[86]

Tourism

The positive image of progress was enhanced by the promotion of the south and south-west as holiday destinations. "Sunny South Sam" became a character that embodied the railway, whilst slogans such as "Live in Kent and be content" encouraged commuters to move out from London and patronise the Southern Railway's services.[87] Posters also advertised ocean services from Ocean Terminal in Southampton and the docks at Dover. These also incorporated the corresponding rail connections with London, such as "The Cunarder" and the "Golden Arrow".[86]

Heritage

The Southern Railway's memory lives on at several preserved railways in the south of England, including the Watercress Line, the Swanage Railway, the Spa Valley Railway, the Bluebell Railway, the Isle of Wight Steam Railway and the Dartmoor Railway. Other remnants of the railway include Eastleigh works and the London termini, including Waterloo (the largest London railway station), Victoria, Charing Cross, Cannon Street and London Bridge (the oldest London terminus). Several societies promote continued interest in the SR, such as the Southern Railways Group and the Southern Electric Group.

Notable people

Chairmen of the board of directors

- Sir Hugh Drummond (1923–1 August 1924). Drummond had been chairman of the London and South Western Railway since 1911. He died in office.

- The Honourable Everard Baring (1924–7 May 1932). Died in Office.

- Gerald Loder (1932–December 1934). Became Lord Wakehurst in June 1934, and resigned at the end of the year.

- Robert Holland-Martin (1935–26 January 1944). Died in office.[90]

- Colonel Eric Gore-Brown (February 1944–nationalisation).[90]

General managers

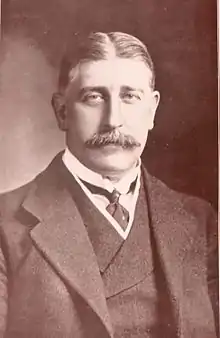

Sir Herbert Ashcombe Walker, KCB, (1923–1937). Walker was an astute administrator of railways, having gained experience as General Manager of the LSWR from 1912. After retiring in 1937 he was a director of the Southern until the end of its existence in 1947. Two significant events occurred under Walker's tenure as General Manager: electrification in the mid-1920s and the appointment of Bulleid as CME in 1937.

Gilbert S. Szlumper, TD, CBE, (1937–1939). Trained as a civil engineer and became Docks and Marine Manager at Southampton, before becoming Assistant General Manager in 1925. In 1939 the War Office recalled him as a Major-General to sort out the military movements at Southampton Docks. He was ousted from the General Managership after the Traffic Manager, Eustace Missenden, refused to become Acting General Manager, and threatened to resign if not confirmed as GM proper.

Sir Eustace Missenden(1939–Nationalisation); Chairman, Railway Executive (1947–1951). Missenden was traffic manager before becoming General Manager 1939. From the latter half of 1947, he was largely absent from the Southern Railway as Chairman of the Railway Executive.

Sir John Elliot Acting General Manager (1947); Assistant General Manager (1933 to nationalisation); Public Relations Assistant (1925–1933). Noted for being Britain's first expert in public relations, Elliot was brought in by Sir Herbert Walker after bad press was received following service delays and consolidation of the newly created company. Elliot suggested that the Southern's express passenger locomotives should be named, representing positive publicity for the railway, while distinctive locomotive liveries and well-known posters were created under his direction. He continued to serve the railways after nationalisation in 1948, and became Chairman of London Transport in 1953.

Chief mechanical engineers

R. E. L. Maunsell, the Southern's first chief mechanical engineer (1922 to 1937). Maunsell was responsible for initial attempts at locomotive standardisation on the Southern, as well as overseeing the introduction of electric traction. Among his many achievements was the introduction of the 4-6-0 SR Lord Nelson Class locomotives and also the SR Class V or "Schools" class, which were the ultimate and very successful development of the British 4-4-0 express passenger type. He also introduced new, standardised rolling stock designs for use on the Southern network, which were based upon the railway's composite loading gauge.

O. V. S. Bulleid, CBE (CME 1937 to nationalisation). Bulleid moved to the Southern from the LNER, bringing several ideas for improving the efficiency of steam locomotives. Such innovations were used on the Merchant Navy class, West Country and Battle of Britain classes ("Bulleid Light Pacifics"), Q1 and experimental Leader designs. He also developed innovative electric units and locomotives.

Other engineers

Alfred Raworth (1882–1967) was chief electrical engineer to the Southern Railway from 1938 until 1946. He had joined the London and South Western Railway in 1912. After retirement he became a consulting engineer to the English Electric Company.[91]

Alfred Szlumper (1858-1934) was Chief Engineer to the Southern Railway from 1924 to 1927, when he retired.[92] He was the father of Gilbert Szlumper who was later the General Manager of the Southern Railway.

Footnotes

- Marshall, pp. 61

- Marshall, pp. 202

- White (1961), p.30.

- Wolmar, pp. 72–74

- Turner, pp. 215–16.

- Whitehouse, & Thomas, pp. 11–12.

- Wolmar, p. 138.

- Nock, pp. 139–151.

- Wolmar, p. 228

- Marshall, pp. 393–7

- Whitehouse & Thomas, p. 15

- White 1969, p. 181.

- White 1969, pp. 182–183.

- White 1969, p. 183.

- White 1969, p. 182.

- White 1969, p. 184.

- White 1969, p. 193.

- Moody, pp. 56–75

- Hendry, p. 21

- Hendry, p. 23

- Hendry, p. 50

- Cooke, B.W.C., ed. (September–October 1949). "End of Southern Railway Company". The Railway Magazine. Westminster: Railway Publishing Company. 95 (583): 282.

- "Main-Line Companies Dissolved". The Railway Magazine. London: Transport (1910) Ltd. 96 (586): 73. February 1950.

- "No. 38637". The London Gazette. 10 June 1949. p. 2886.

- Hendry, p. 58

- "Govia". Go Ahead Group. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Earnshaw, Alan (1989). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 5. Penryn: Atlantic Books. pp. 22, 30. ISBN 0-906899-35-4.

- "Accident at Sevenoaks on 24th August 1927". Railway Archive. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Trevena, Arthur (1980). Trains in Trouble. Vol. 1. Redruth: Atlantic Books. p. 37. ISBN 0-906899-01-X.

- Hoole, Ken (1982). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 3. Redruth: Atlantic Books. pp. 30, 32–33, 38. ISBN 0-906899-05-2.

- "Accident at Battersea Park on 2nd April 1937". Railway Archive. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Hall, Stanley (1990). The Railway Detectives. London: Ian Allan. p. 101. ISBN 0-7110-1929-0.

- Bishop, Bill (1984). Off the Rails. Southampton: Kingfisher. pp. 21, 25. ISBN 0-946184-06-2.

- Earnshaw, Alan (1993). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 8. Penryn: Atlantic Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-906899-52-4.

- Trevena, Arthur (1981). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 2. Redruth: Atlantic Books. p. 33. ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- "Accident at South Croydon on 24th October 1947". Railway Archive. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Turner, John Howard (1977). The London Brighton and South Coast Railway 1 Origins and Formation. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0275-X. p.118.

- Southern Named Trains "Thanet/Kentish Belle" http://www.semgonline.com/misc/named_05.html

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 30

- "London & South Western Railway, Page 1: Services From Southampton". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, Page 1: Newhaven-Dieppe". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "South Eastern & Chatham Railway". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- Hendy, John (1989). Sealink Isle Of Wight. Staplehurst: Ferry Publications. pp. 20–25. ISBN 0-9513093-3-1.

- "Southern Railway, SR Page 1: Dover and Folkestone Services". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "Southern Railway, SR Page 2: Newhaven Services". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "Southern Railway, SR Page 3: Southampton Services". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "Isle of Wight Services, SR Page 4: Southern Railway Paddle Steamers". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "Ts Maidstone (II), Past and Present". Dover Ferry Photos Forums. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Rebuilding of Cannon Street Station". The Times. 17 November 1955.

- P. J. G. Ransom, Section LBSCR

- "Southern Vectis - Who we are". www.islandbuses.info. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- "New Land Airport". The Times (48219). London. 2 February 1939. col F, p. 12.

- "Southern Railway Company". The Times (47619). London. 26 February 1937. col A-E, p. 22.

- "Southern Railway Company". The Times (47928). London. 25 February 1938. col A-E, p. 24.

- Haresnape. p. 124

- Burridge, p. 60

- Marshall, p.393.

- The ABC of British Locomotives, Part 2, pp. 41–6.

- Clarke: Steam World (April 2008), p. 50

- Swift, p. 9

- Whitehouse, & Thomas, p. 47

- Southern E-Group (2004), Retrieved 10 September 2008. For information on influence.

- Herring, pp. 124–125

- Bulleids in Retrospect

- Creer & Morrison, p. 21

- Herring, p. 150–151

- Morgan, pp. 17–19

- Morgan, p. 19

- Bulleid, Section "Leader class"

- Haresnape, Section 4

- Day-Lewis, p. 7

- Day-Lewis, p. 6

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 24

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 25

- Moody p.25.

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 28

- Bradley p.71.

- Bradley 1975, p. 72

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 18

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), p. 10

- Robertson, p. 96

- Robertson, p. 41

- Whitehouse, & Thomas, p. 18

- Whitehouse, & Thomas, p. 115

- Whitehouse, & Thomas, p. 114

- Thomas & Whitehouse (1988). p.205.

-

- "OBITUARY. ALFRED RAWORTH, 1882-1967". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. London: ICE Publishing. 38:4: 828–829. 1967. doi:10.1680/iicep.1967.8213.

- "Alfred Weeks Szlumper". The Engineer. 16 November 1934.

Bibliography

- Bonavia, Michael R. (1987). History of the Southern Railway. London: Unwin Hyman. ISBN 0-04-385107-X.

- Bradley, D.L. (October 1975). Locomotives of the Southern Railway, part 1. London: RCTS. ISBN 0-901115-30-4. OCLC 499812283.

- Bulleids in Retrospect, Transport Video Publishing, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire

- Harvey, R. J.: Bulleid 4-6-2 Merchant Navy Class (Locomotives in Detail series volume 1) (Hinckley: Ian Allan Publishing, 2004) ISBN 0-7110-3013-8

- Haresnape, B.: Maunsell locomotives (Ian Allan Publishing, 1978) ISBN 0-7110-0743-8

- Herring, Peter: Classic British Steam Locomotives (London: Abbeydale, 2000) Section "WC/BB Class" ISBN 1-86147-057-6

- Ian Allan ABC of British Railways Locomotives. Part 2, 1949 edition.

- Ian Allan ABC of British Railways Locomotives, winter 1958–59 edition

- Marshall, C.F. Dendy: History of the Southern Railway, (revised by R.W. Kidner), (London: Ian Allan, 1963) ISBN 0-7110-0059-X.

- Moody, G.T. (1963). Southern Electric 1909–1963. London: Ian Allan Publishing.

- Nock, O.S. (1961). The South Eastern and Chatham Railway. London: Ian Allan.

- The Railway Magazine (November 2008), Southern Railway souvenir issue

- Turner, J.T. Howard: The London Brighton and South Coast Railway. 3 Completion and Maturity (London: Batsford, 1979). ISBN 0-7134-1389-1.

- Whitehouse, Patrick & Thomas, David St.John: SR 150: A Century and a Half of the Southern Railway (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 2002).

- Wolmar, Christian (2007). Fire and Steam: How the Railways Transformed Britain. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.

- White, H.P. (1969). Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Southern England v. 2. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4733-0.

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern Railway (Great Britain). |

- Southern Railways Group – specialist society for the railways of Southern England, especially The Southern Railway, its predecessors and successors, publishers of a quarterly journal and bi-monthly newsletter, centre of excellence for research

- Southern E-mail Group – extensive source of information concerning the Southern Railway, its predecessors and successors

- Southern Electric Group

- Southern Posters – collection of Southern Railway promotional material

- George Keen GM – First railway worker to be awarded the George Medal, 1940

- Works by or about Southern Railway in libraries (WorldCat catalog)