Spanish crisis of 1917

The Crisis of 1917 is the name that Spanish historians have given to the series of events that took place in the summer of 1917 in Spain. In particular, three simultaneous challenges threatened the government and the system of the Restoration: a military movement (the Juntas de Defensa), a political movement (the Parliamentary Assembly, organized by the Regionalist League of Catalonia in Barcelona), and a political movement (a general strike). These events coincided with a number of critical international events that same year. However, in world history this period is not typically referred to as a crisis, and the term is instead reserved for specific issues relating to World War I, such as the conscription crisis in Canada and the crisis of naval construction in the United States.[1] Spain remained neutral throughout the conflict.

International Events

In Russia, the February Revolution of 1917 had overthrown the Tsarist autocracy. The Kerensky government was attempting to build a democratic system while continuing the war against the Central Powers, a disaster in military, economic, and human terms. The Bolsheviks took advantage of the growing discontent to seize power in the October Revolution that year.[2]

World War I had entered a phase of uncertainty, since Germany's advantage on the eastern front was offset by the United States entering the war on 6 April and destabilizing the western front.

Although its effects had yet to manifest during the Crisis of 1917, the Spanish Flu was developing in the winter of 1917-1918, and would become the deadliest pandemic of the Late Modern Period. It received its name because Spanish newspapers, free from wartime censorship due to Spain's neutrality, were the first to report on it. The death toll of 50 to 100 million would greatly surpass the deaths of World War I, which contributed enormously to the spread of the epidemic around the world at a scale and speed never before experienced. The effects on Spain were dire: 8 million infected and 300,000 dead, although official statistics put the number of dead at 147,114.[3]

The Crisis in Spain

Economy and Society

Spain's neutrality in World War I increased a number of its exports, from agricultural and mineral raw materials to manufactured goods from the emerging industrial sector, particularly Catalonian textiles and Basque ironworks. The balance of trade grew from a deficit of more than one hundred million pesetas to a surplus of five hundred million pesetas.[4] This economic boom favored the industrial and commercial middle class and the financial and land-owning oligarchy, but also produced rising inflation while salaries stagnated. As profits were experiencing extraordinary growth rates, standards of living decreased significantly for the general populace, especially for the urban and industrial proletariat, although they were able to maintain pressure to achieve higher wages. In the countryside the situation was different: inflation had a greater impact, but more direct food availability lessened its effects on small landowners and tenants, predominant in the agrarian structure of northern Spain. It was quite the opposite, however, for landless laborers, a fundamental part of the workforce in the southern half of Spain, especially in Andalusia and Extremadura. The result of the process, already acutely visible in 1917, was a radical redistribution of national income, both between social classes and among territories. Rural exodus and disproportionate development between the industrial and agricultural sectors progressively worsened rural-urban tensions and the center-periphery.[5]

Military challenge: The Juntas de Defensa

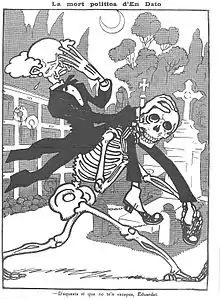

The Juntas de Defensa were a military union movement created without the approval of the Spanish legislature, and represented a clear challenge to the liberal government of Manuel García Prieto, who, unable to control them, was forced to resign. His replacement, the conservative Eduardo Dato, legalized the Juntas.

The Juntas selected a name that was common among Spanish institutions and had credibility from its use in the popular uprising of the War for Independence. They claimed that their purpose was to defend the interests of mid-ranking military officials, but their goal of political intervention was clear.

The military’s obsession with national unity had become one if its greatest mobilizing factors, manifesting in the 1905 attack on the satirical Catalan publication, ¡Cu-Cut!. After the attack, the governor attempted to appease them by passing the Law of Jurisdictions, which gave the military jurisdiction over "oral and written offenses against national unity, the flag, or the military’s honor." Members of the military found themselves in a peculiar social situation: soldiers in almost every other world military were experiencing great social mobility on the merits of war and the need to recruit huge numbers of soldiers, while Spanish soldiers were reduced to inaction. They could not even be compensated with stations in the colonies, since those had been lost in the Spanish-American War of 1898. In fact, the Spanish military had an overabundance of officers, with 16,000 officers per 80,000 soldiers, compared to France’s 29,000 officers per 500,000 soldiers.[6] Resentments within the army were developing between the only colonial destinations in Morocco and the rest. Inflation continued to diminish the buying power of military salaries, which were set by the rigid state budget, unlike the more flexible contracts of workers.

The Juntas’ activities began in the first quarter of 1916, due to part of Governor Conde de Ramanones’ modernization program, which would require soldiers to pass aptitude tests to qualify for promotions. The governor accepted their protests initially, but after seeing the danger of a quasi-union movement in the army, ordered the Juntas to disband, although to little effect.[6] Even operating illegally, they had grown more outspoken since the end of 1916. Above all, the Junta de Defensa of the Barcelona Infantry, directed by Colonel Benito Márquez, had become the most active promoters of the movement. At the end of May 1917, they incurred a strong disciplinary reaction from the new government, directed at the time by García Prieto. The Minister of War, General Aguilera, ordered the arrest of various Junta members in Montjuïc Castle: two lieutenants, three captains, a commander, a lieutenant colonel, and Col. Benito Márquez, the most visible leader of the movement. Nevertheless, the immediate establishment of an Acting Junta, supported by the Artillery and Engineering Juntas, and even the Civil Guard in its “respectful” request on 1 June to free those arrested, resulted in a spectacular increase in military tension, which García Prieto did not have the support to confront. Prieto opted to resign, and King Alfonso XIII, who had a close relationship with the military, ordered Eduardo Dato to form a government. Dato’s government decided to give in to the military’s demands, liberate those arrested, and legalize the Juntas. In order to maintain tight control of the situation, the new government suspended constitutional guarantees and increased censorship of the press.[6][7]

Political Challenge

Led by Fransesc Cambó, the Regionalist League of Catalonia represented the Catalan bourgeoisie. They had recently acquired a local power base through the formation of the Commonwealth of Catalonia, which arose in 1914 as an aggregation of the Provincial Councils. Prat de la Riba had been the first leader of the Commonwealth, and died in 1917. In light of the open crisis, Cambó called on the government to convene the Parliament, but was refused. Facing this denial, and the impossibility of using ordinary parliamentary channels because the sessions of Congress had not convened, a large part of the deputies elected by the Catalan constituencies (48, all except those of the dynastic parties), met in the so-called Assembly of Parliaments of Barcelona at the beginning of July 1917. The Assembly demanded the convening of a constitutional assembly with the goal of re-structuring the government to recognize regional autonomy. They also demanded measures in the military and economic sectors. It was highly unlikely the Assembly could connect its movement to the economic discontent of the low-ranking officers in the Juntas de Defensa, but they made their attempt to do so explicit in a proclamation which declared:

The act committed by the Army on the first of June will be followed by a profound renovation of Spanish public life, undertaken and achieved by political elements.

Even though the Assembly represented less than 10% of the total deputies, a pre-revolutionary atmosphere persisted, which questioned the fundamentals of the political system of the Restoration: the turno of the dynastic parties founded by Cánovas and Sagasta, the clear predominance of the executive branch over the legislative, and the king's arbitration role. Dato responded by declaring the Assembly seditious, suspending newspapers, and sending the military to occupy Barcelona. In mid July, the Assembly met again in the Salón de Juntas in the palace of Parc de la Ciutadella. In total 68 deputies attended, with additions from other regions such as the republican Alejandro Lerroux, the reformist Melquiades Álvarez, and a single socialist deputy, Pablo Iglesias, who was already preparing the strike movement planned for the following month. The gathered deputies agreed that “the convening of the Parliament, which, in constituent functions, can deliberate on these problems [of the country] and resolve them, is essential.” But, they added, the Parliament could not be convened by a divided government, but only by “a government that embodies and represents the sovereign will of the country.”[8] They agreed to meet again on 16 August in Oviedo, but the dissolution of the Assembly by security forces on 19 July and the subsequent events prevented them.[9] Antonio Maura’s sought-after participation never took place.[10]

Social Challenge

Barcelona, the economic capital of Spain,[11] was especially conflicted, as demonstrated by the Tragic Week of 1909, and the social crisis was faced with a workers movement. Socialists and anarchists fought against employers, with employers utilizing all manner of tactics, from scabs to pistolerismo. Socialists and anarchists employed peaceful tactics such as strikes, as well as direct actions which sometimes took the form of indiscriminate attacks, like the 1893 bombing of the Liceu in Barcelona. The workers movement in other parts of Spain was less developed, but saw the opportunity to exploit the weakness of the conflict between the industrial bourgeoisie and the government. The UGT, an established socialist union in Madrid and Basque Country, organized a revolutionary general strike in August 1917, which received the support of CNT, an anarchist union operating mainly in Catalonia. The two unions had been approaching unity, at least in their actions, since the strike in December 1916 and the so-called Zaragoza Pact. The agreement on a general strike was made in Madrid at the end of March 1917 by UGT members Julián Besteiro and Francisco Largo Caballero and CNT members Salvador Seguí and Ángel Pestaña, and included an extensive manifesto:[7]

With the goal of holding the ruling classes to those fundamental changes of the system that guarantee the public, at minimum, decent living conditions and the development of their self-emancipation, the proletariat of Spain must employ a general strike, with no specified end date, as the strongest weapon that it possesses in reclaiming its rights.

In spite of objections from the anarchists, negotiations began with the bourgeois parties, namely Alejandro Lerroux’s republicans. They discussed the formation of a provisional government, with the moderate Melquiades Álvarez as president and Pablo Iglesias as minister of labor.

Calls for the strike were ambiguous, with early messaging describing a revolutionary strike, and later communications insisting on its peaceful nature. Above all the UGT tried to consciously avert partial, sectarian, or local strikes. Nevertheless, the lengthy preparations for the strike worked against it. The arrest of those who had signed the manifesto, closure of the socialists’ meeting place, the Casa del pueblo, and a number of government maneuvers dispersed the strikers' efforts, most notably in the UGT railroad workers strike in Valencia on 9 August in protest of the detentions, but with internal labor motives that precipitated the addition of other sections of the union across the country between August 10 and 13. [12]

Even so, the strike initially managed to halt activity in almost every major industrial zone (Biscay and Barcelona, as well as some smaller one like Yecla and Villena), urban centers (Madrid, Valencia, Zaragoza, A Coruña), and mines (Río Tinto, Jaén, Asturias, and León), but only for one week in total. Small cities and rural areas were barely impacted. Railway communication, a key sector, was only briefly disrupted.[13]

Conclusions

The three challenges to the government from the military, Catalan, and the proletariat sparked fears of a revolution, as had occurred in Russia. However, the army rapidly carried out the government’s orders and suppressed the strike within three days, with exception to some areas such as Asturia’s mining basins, where the conflict lasted nearly a month. Col. Márquez himself stood out in the repression of the revolt in Sabadell. The intervention of the army, in addition to its violence against the strikers, resorted to extreme measures with little respect to institutional norms, such as the violation of the parliamentary immunity of a republican deputy detained by the Captain General of Cataluña.[12]

Meanwhile, the Regionalist League of Catalonia, wary of the social unrest, chose to support a nationally unified government with active support from the king. García Prieto once again presided over the government, which included Cambó and committed to holding elections in February 1918, the outcome of which was uncertain, with no clear majority for any party. This situation was unprecedented. Typically, “single-color” governments did not come to power by winning elections, but through appointment by the king. They would conveniently prepare the elections themselves by getting an easily controlled parliament and pigeonholing their candidates, who were guaranteed election through caciquismo, pucherazo, or open fraud when necessary. This typical scenario was prevented in this case by a multiparty composition, thereby forcing a new nationally unified government, this time led by Maura. This occurred again in the following elections in June 1919, and the return to traditional turnismo did not occur until the elections of December 1920, which were organized single-handedly by Dato.

In August 1917, members of the strike committee, among which stood out future socialist leaders Francisco Largo Caballero and Julián Besteiro (Pablo Iglesias was in the final years of his life) were detained, tried, and jailed with life sentences, although they were all still elected as deputies in the elections of February 1918. The scandal of keeping deputies with parliamentary immunity in prison led to their release after an extensive campaign that counted among its supporters intellectuals such as Manuel García Morente, Gumersindo de Azcárate, and Gabriel Alomar. Indalecio Prieto had fled to France and was able to return to reclaim his position as deputy in April 1918. Strike committee members Daniel Anguiano and Andrés Saborit had also been imprisoned. The republican Marcelino Domingo was pardoned in November. The repression of the strike left a total of 71 dead, 156 injured, and about two thousand arrested. [14]

The repressions strengthened the close relationship between the king and the army, as well as their role in public life. Large parts of the population, including intellectuals and the working and middle classes, became increasingly disaffected with the political system, which had received many regenerationist criticisms since the end of the 19th century, such as Joaquín Costa’s calls for an iron surgeon. The identity of this rhetorical figure was disputed, but would finally arise in the next serious crisis, the Battle of Annual. As the institution with the greatest display of power, the army produced the iron surgeon in the person of the Captain General of Barcelona, Miguel Primo de Rivera. At the acquiescence of the king and empowered by the Catalan bourgeoisie, he assumed the power of the dictator in 1923.

Notes

- William J. Williams (1992) The Wilson Administration and the Shipbuilding Crisis of 1917: Steel Ships and Wooden Steamers, Edwin Mellen Press ISBN 0-7734-9492-8

- Edward Acton (1990). Rethinking the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-7131-6530-2. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Trilla, Antoni (2008). "The 1918 "Spanish Flu" in Spain". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 47: 668–673.

- Garcia Queipo 1996, p. 18.

- José Luis García Delgado Proceso inflacionista y política económica. Algunas conclusiones [Inflationary process and policy. Some conclusions in The Spanish economy between 1900 and 1923] in Tuñon de Lara (Ed.), pgs. 447-448.

- Garcia Queipo 1996, p. 56.

- Ruiz González 1984, p. 498.

- Juliá Díaz, Santos (2009). La Constitución de 1931. Madrid: Iustel. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-84-9890-083-5. OCLC 638806740.

- Ruiz González 1984, p. 498-499.

- Garcia Queipo 1996.

- This classification was widely used at the time, and follows both opinion and objective data, such as population figures and economic production. Juan Velarde Fuertes gives a contemporary interpretation of the succession of economic capitals in Spain in "El ímpetu económico de Madrid" "[The Economic Impetus of Madrid]" (ABC, 04-30-2007)

During the first era of the Industrial Revolution, that of coal, railways, and textile production, the economic capital of Spain was Barcelona; during the second era, that of the automotive, chemical and electric industries, the capital was unquestionably Bilbao; and in the third era, that of ICT, globalization and lessening economic interventionism, it is Madrid.

- Garcia Queipo 1996, p. 60.

- Ruiz González 1984, p. 500-501.

- Ruiz González 1984, p. 502.

References

- Balanzá, M. Roig, J. et. al. (1994). Ibérica: Geografía e historia de España y de los países Hispánicos. [Iberia: Geography and History of Spain and Hispanic countries.] Barcelona: Vicens Vives. ISBN 84-316-2437-X

- Garcia Queipo, G. (1996). El reinado de Alfonso XIII. La modernización fallida. [The reign of Alfonso XIII. Modernization failed.] Madrid: Issues of Today. ISBN 84-7679-318-9

- Martinez Cuadrado, M. (1973). La burguesía conservadora (1874-1931). [The conservative middle class (1874-1931).] 7th edition. History of Spain. Madrid: Alianza. 1981. ISBN 84-206-2049-1

- Ruiz González, D. (1984). La crisis de 1917. In M. Tuñon de Lara (Ed.) Historia de España: Revolución burguesa, oligaquía y constitucionalismo (1834-1923) [History of Spain: Bourgeois revolution, oligarchy and constitutionalism (1834-1923) (2nd ed.,Vol.8). Barcelona: Labor. ISBN 84-335-9439-7