Squib (explosive)

A squib is a miniature explosive device used in a wide range of industries, from special effects to military applications. It resembles a tiny stick of dynamite, both in appearance and construction, although with considerably less explosive power. Squibs consist of two electrical leads, which are separated by a plug of insulating material, a small bridge wire or electrical resistance heater, and a bead of heat-sensitive chemical composition, in which the bridge wire is embedded.[1] Squibs can be used for generating mechanical force or to provide pyrotechnic effects for both film and live theatrics. Squibs can be used for shattering or propelling a variety of materials.[2]

A squib generally consists of a small tube filled with an explosive substance, with a detonator running through the length of its core, similar to a stick of dynamite. Also similar to dynamite, the detonator can be a slow-burning fuse, or as is more common today, a wire connected to a remote electronic trigger.[3] Squibs range in size, anywhere from 0.08" up to 0.6" (~2 to 15 millimeters) in diameter.[2]

History

Squibs were originally made from parchment tubes, or the shaft of a feather, and filled with fine black powder. They were then sealed at the ends with wax. They were sometimes used to ignite the main propellant charge in cannon.[4]

Squibs were once used in coal mining to break coal away from rock. In the 1870s, some versions of the device were patented and mass-produced as "Miners' Safety Squibs".[5]

The famous "Squib Case"

Squibs are mentioned in the prominent tort case from eighteenth-century England, Scott v. Shepherd, 96 Eng. Rep. 525 (K.B. 1773). A lit squib was thrown into a crowded market by Shepherd and landed on the table of a gingerbread merchant. A bystander, to protect himself and the gingerbread, threw the squib across the market, where it landed in the goods of another merchant. The merchant grabbed the squib and tossed it away, accidentally hitting Scott in the face, putting out one of his eyes.

Squibs in film

The first documented use of squibs to simulate bullet impacts in movies was in the 1955 Polish film Pokolenie by Andrzej Wajda, where for the first time audiences were presented with a realistic representation of a bullet impacting on an on-camera human being, complete with blood spatter. The creator of the effect, Kazimierz Kutz, used a condom with fake blood and dynamite.[6]

Origin of the phrase "damp squib"

| Look up damp squib in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

While most modern squibs used by professionals are insulated from moisture, older uninsulated squibs needed to be kept dry in order to ignite, thus a "damp squib" was literally one that failed to perform because it got wet. Often misheard as "damp squid",[7] the phrase "damp squib" has since come into general use to mean anything that fails to meet expectations.[8] The word "squib" has come to take on a similar meaning even when used alone, as a diminutive comparison to a full explosive.[9]

Modern day uses

Film industry

Today, squibs are widely used in the motion picture special effects industry and theatre productions to portray bullet impacts on inanimate objects or on actors. Simulants such as sand, soil, wood, splinters or in the case of the latter, fake blood, dust [10], down feathers [11] (for the desired stylistic gunshot effect on a down jacket if that is the actor's costume), or other materials to simulate shattered bone and tissue, may be attached to the squib to simulate the impact that occurs when bullets pierce through different materials.

In the North American film industry, the term squib is often used to refer variously to electric matches and detonators (used as initiators to trigger larger pyrotechnics). Squibs are generally (but not always) the main explosive element in an effect, and as such are regularly used as “bullet hits” [12]. Conventional squibs fire once, with the exception of eSquibs (proprietary), which fire 200 or more times before depletion.[13]

In the case of simulating bullet hits on actors, a special effects technician will build a "blood squib" or a "blood pack" device for the required scene. A small balloon, packet or condom is filled with a simulant, which is coupled to the squib and a protective plate and padding. [14] Depending on the weight and thickness of the costume fabric, the blood packs are either taped to the inside of the costume (e.g. jacket) or on the actor (e.g. shirt). Bullet holes on the wardrobe fabric are scored [15], grated from the inside and/or cut carefully, taped back together and secured on top of the blood pack. If inner lining is present, it is removed to access the site and to make the area as thin as possible [16][17]. More specifically on down jackets mentioned earlier, the down is repacked in a sealed "pocket" behind the blood pack to prevent it from leaking out and to maintain the quilted puffer appearance. The blood packs are then connected to a power source (e.g. battery) and sometimes also to a programmable controller. Finally, blood packs can be triggered wired or wirelessly by a crew member off camera or by the actor him/herself. The squib should propel the fake blood or other simulants away from the actor and rip open the weakened/scored area of the costume fabric. After the squibs have been triggered, bullet holes may be enhanced and the blood packs and/or the costume may be removed by the wardrobe department for retake, redressing or cleaning up. A well-made, low profile bullet hit squib device should not be visible beneath the costume, neither should the pre-scoring of the fabric be visible if it is properly made, although typically in post-production, only the detonation sequence is shown immediately in a cut. An identical costume is used in scenes prior to that. Bullet hit squibs require multiple sets of costumes - typically at least three - just for the scene, as the wardrobe fabric is torn and cannot be reused [18]. The time, personnel and material costs for resets can therefore be high for independent/low budget filmmakers.

More advanced devices and alternative methods have been developed in recent years, primarily by means of pneumatics (compressed gas) [19]. These devices are safer for the actor and do not require specialised pyrotechnicians, which also reduce cost. While they are reusable, they are bulkier and heavier, and is not preferred for multiple bullet hits [20], as well as being more difficult to control [21]. Pneumatic alternates may still be referred to as "squibs", even though they do not use explosive substances.

Automotive industry

Squibs are used in emergency mechanisms where gas pressure needs to be generated quickly in confined spaces, while not harming any surrounding persons or mechanical parts. In this form, squibs may be called gas generators. One such mechanism is the inflation of automobile air bags.

Aerospace industry

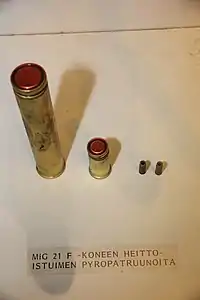

In military aircraft, squibs are used to deploy countermeasures and are also implemented during ejection to propel the canopy and ejection seat away from a crippled aircraft. They are also used to deploy parachutes.[3]

Other uses

Squibs are also used in automatic fire extinguishers, to pierce seals that retain liquids such as halon, fluorocarbon, or liquid nitrogen.

See also

References

- Thibodaux, J. G. (July 1, 1961). "Special Rockets and Pyrotechnics Problems". Langley Research Center. NTRS. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions". Fantasy Creations FX.

- US 5411225 “Reusable non-pyrotechnic countermeasure dispenser cartridge for aircraft”.

- Calvert, James B. "Cannons and Gunpowder". University of Denver. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01.

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. (1988). St. Clair, a nineteenth-century coal town's experience with a disaster-prone industry. Cornell University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8014-9900-5.

- "Pokolenie". Gazeta Wyborcza. 2008. Archived from the original on 2012-06-03.

- "Damp Squid: The top 10 misquoted phrases in Britain". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 February 2009.

- "Definition of damp squib". Allwords.com.

- "squib: Definitions, Synonyms". Answers.com.

- "Professional Bullet Hit Effects". Roger George Special Effects. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- FX (1996). "Fargo (1996) Kill Count". YouTube.

- Fantasy Creations FX. "Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions".

- LDI 2014 Award Winners Announced. Nov 22, 2014, livedesignonline.com, accessed 20 May 2019.

- Grossman, Andrew. "Bleeding Realism Dry". Bright Lights Film Journal. p. 2.

- "The Hit Kit - Bullet Hit Squib Kit for Professional Pyrotechnicians". Roger George Special Effects. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "How to blow up a car (in the movies)". BBC News. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "Working with Blood on Costumes". ProductionHUB.com. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- dontshootthecostumer (2013-04-14). "B IS FOR…". Don't Shoot the Costumer. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "Tolin FX". Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "HitFX Theatrical Squib & Bullet Hit Effects - Film & TV". www.bloodystuff.co.uk. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "The Little Squib that Couldn't Splatter Blood". The Black and Blue. 2011-07-29. Retrieved 2021-02-06.