Bone

A bone is a rigid tissue that constitutes part of the vertebrate skeleton in animals. Bones protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and enable mobility. Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes and have a complex internal and external structure. They are lightweight yet strong and hard, and serve multiple functions.

| Bone | |

|---|---|

A bone dating from the Pleistocene Ice Age of an extinct species of elephant | |

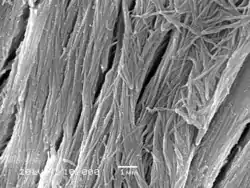

A scanning electronic micrograph of bone at 10,000× magnification | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001842 |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 366, 377 |

| TH | H3.01.00.0.00001 |

| FMA | 5018 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Bone tissue (osseous tissue) is a hard tissue, a type of specialized connective tissue. It has a honeycomb-like matrix internally, which helps to give the bone rigidity. Bone tissue is made up of different types of bone cells. Osteoblasts and osteocytes are involved in the formation and mineralization of bone; osteoclasts are involved in the resorption of bone tissue. Modified (flattened) osteoblasts become the lining cells that form a protective layer on the bone surface. The mineralized matrix of bone tissue has an organic component of mainly collagen called ossein and an inorganic component of bone mineral made up of various salts. Bone tissue is a mineralized tissue of two types, cortical bone and cancellous bone. Other types of tissue found in bones include bone marrow, endosteum, periosteum, nerves, blood vessels and cartilage.

In the human body at birth, there are approximately 270 bones present; many of these fuse together during development, leaving a total of 206 separate bones in the adult, not counting numerous small sesamoid bones.[1][2] The largest bone in the body is the femur or thigh-bone, and the smallest is the stapes in the middle ear.

The Greek word for bone is ὀστέον ("osteon"), hence the many terms that use it as a prefix—such as osteopathy.

Structure

Bone is not uniformly solid, but consists of a flexible matrix (about 30%) and bound minerals (about 70%) which are intricately woven and endlessly remodeled by a group of specialized bone cells. Their unique composition and design allows bones to be relatively hard and strong, while remaining lightweight.

Bone matrix is 90 to 95% composed of elastic collagen fibers, also known as ossein,[3] and the remainder is ground substance.[4] The elasticity of collagen improves fracture resistance.[5] The matrix is hardened by the binding of inorganic mineral salt, calcium phosphate, in a chemical arrangement known as calcium hydroxylapatite. It is the bone mineralization that give bones rigidity.

Bone is actively constructed and remodeled throughout life by special bone cells known as osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Within any single bone, the tissue is woven into two main patterns, known as cortical and cancellous bone, and each with different appearance and characteristics.

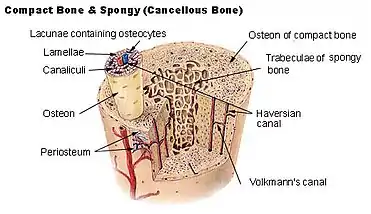

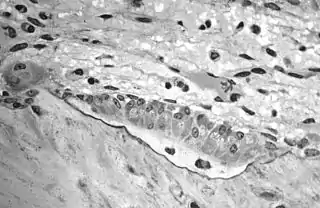

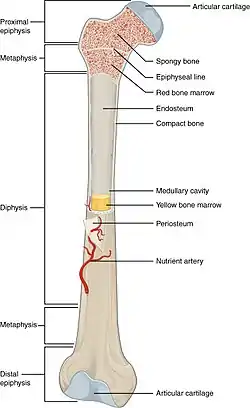

Cortical bone

The hard outer layer of bones is composed of cortical bone, which is also called compact bone as it is much denser than cancellous bone. It forms the hard exterior (cortex) of bones. The cortical bone gives bone its smooth, white, and solid appearance, and accounts for 80% of the total bone mass of an adult human skeleton.[6] It facilitates bone's main functions—to support the whole body, to protect organs, to provide levers for movement, and to store and release chemical elements, mainly calcium. It consists of multiple microscopic columns, each called an osteon or Haversian system. Each column is multiple layers of osteoblasts and osteocytes around a central canal called the haversian canal. Volkmann's canals at right angles connect the osteons together. The columns are metabolically active, and as bone is reabsorbed and created the nature and location of the cells within the osteon will change. Cortical bone is covered by a periosteum on its outer surface, and an endosteum on its inner surface. The endosteum is the boundary between the cortical bone and the cancellous bone.[7] The primary anatomical and functional unit of cortical bone is the osteon.

Cancellous bone

Cancellous bone, also called trabecular or spongy bone,[7] is the internal tissue of the skeletal bone and is an open cell porous network. Cancellous bone has a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio than cortical bone and it is less dense. This makes it weaker and more flexible. The greater surface area also makes it suitable for metabolic activities such as the exchange of calcium ions. Cancellous bone is typically found at the ends of long bones, near joints and in the interior of vertebrae. Cancellous bone is highly vascular and often contains red bone marrow where hematopoiesis, the production of blood cells, occurs. The primary anatomical and functional unit of cancellous bone is the trabecula. The trabeculae are aligned towards the mechanical load distribution that a bone experiences within long bones such as the femur. As far as short bones are concerned, trabecular alignment has been studied in the vertebral pedicle.[8] Thin formations of osteoblasts covered in endosteum create an irregular network of spaces,[9] known as trabeculae. Within these spaces are bone marrow and hematopoietic stem cells that give rise to platelets, red blood cells and white blood cells.[9] Trabecular marrow is composed of a network of rod- and plate-like elements that make the overall organ lighter and allow room for blood vessels and marrow. Trabecular bone accounts for the remaining 20% of total bone mass but has nearly ten times the surface area of compact bone.[10]

The words cancellous and trabecular refer to the tiny lattice-shaped units (trabeculae) that form the tissue. It was first illustrated accurately in the engravings of Crisóstomo Martinez.[11]

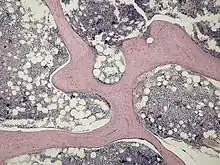

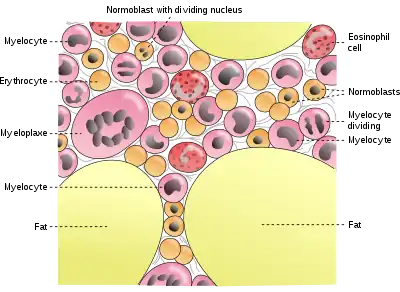

Bone marrow

Bone marrow, also known as myeloid tissue in red bone marrow, can be found in almost any bone that holds cancellous tissue. In newborns, all such bones are filled exclusively with red marrow or hematopoietic marrow, but as the child ages the hematopoietic fraction decreases in quantity and the fatty/ yellow fraction called marrow adipose tissue (MAT) increases in quantity. In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the bone marrow of the femur, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones.[12]

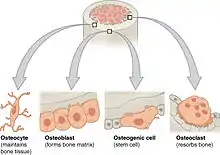

Bone cells

Bone is a metabolically active tissue composed of several types of cells. These cells include osteoblasts, which are involved in the creation and mineralization of bone tissue, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, which are involved in the reabsorption of bone tissue. Osteoblasts and osteocytes are derived from osteoprogenitor cells, but osteoclasts are derived from the same cells that differentiate to form macrophages and monocytes.[13] Within the marrow of the bone there are also hematopoietic stem cells. These cells give rise to other cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.[14]

Osteoblast

Osteoblasts are mononucleate bone-forming cells. They are located on the surface of osteon seams and make a protein mixture known as osteoid, which mineralizes to become bone.[15] The osteoid seam is a narrow region of newly formed organic matrix, not yet mineralized, located on the surface of a bone. Osteoid is primarily composed of Type I collagen. Osteoblasts also manufacture hormones, such as prostaglandins, to act on the bone itself. The osteoblast creates and repairs new bone by actually building around itself. First, the osteoblast puts up collagen fibers. These collagen fibers are used as a framework for the osteoblasts' work. The osteoblast then deposits calcium phosphate which is hardened by hydroxide and bicarbonate ions. The brand-new bone created by the osteoblast is called osteoid.[16] Once the osteoblast is finished working it is actually trapped inside the bone once it hardens. When the osteoblast becomes trapped, it becomes known as an osteocyte.[17] Other osteoblasts remain on the top of the new bone and are used to protect the underlying bone, these become known as lining cells.

Osteocyte

Osteocytes are cells of mesenchymal origin and originate from osteoblasts that have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by bone matrix that they themselves produced.[7] The spaces the cell body of osteocytes occupy within the mineralized collagen type I matrix are known as lacunae, while the osteocyte cell processes occupy channels called canaliculi. The many processes of osteocytes reach out to meet osteoblasts, osteoclasts, bone lining cells, and other osteocytes probably for the purposes of communication.[18] Osteocytes remain in contact with other osteocytes in the bone through gap junctions—coupled cell processes which pass through the canalicular channels.

Osteoclast

Osteoclasts are very large multinucleate cells that are responsible for the breakdown of bones by the process of bone resorption. New bone is then formed by the osteoblasts. Bone is constantly remodeled by the resorption of osteoclasts and created by osteoblasts.[13] Osteoclasts are large cells with multiple nuclei located on bone surfaces in what are called Howship's lacunae (or resorption pits). These lacunae are the result of surrounding bone tissue that has been reabsorbed.[19] Because the osteoclasts are derived from a monocyte stem-cell lineage, they are equipped with phagocytic-like mechanisms similar to circulating macrophages.[13] Osteoclasts mature and/or migrate to discrete bone surfaces. Upon arrival, active enzymes, such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, are secreted against the mineral substrate. The reabsorption of bone by osteoclasts also plays a role in calcium homeostasis.[19]

Composition

Bones consist of living cells (osteoblasts and osteocytes) embedded in a mineralized organic matrix. The primary inorganic component of human bone is hydroxyapatite, the dominant bone mineral, having the nominal composition of Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2.[20] The organic components of this matrix consist mainly of type I collagen—"organic" referring to materials produced as a result of the human body—and inorganic components, which alongside the dominant hydroxyapatite phase, include other compounds of calcium and phosphate including salts. Approximately 30% of the acellular component of bone consists of organic matter, while roughly 70% by mass is attributed to the inorganic phase.[21] The collagen fibers give bone its tensile strength, and the interspersed crystals of hydroxyapatite give bone its compressive strength. These effects are synergistic.[21] The exact composition of the matrix may be subject to change over time due to nutrition and biomineralization, with the ratio of calcium to phosphate varying between 1.3 and 2.0 (per weight), and trace minerals such as magnesium, sodium, potassium and carbonate also being found.[21]

Type I collagen composes 90–95% of the organic matrix, with remainder of the matrix being a homogenous liquid called ground substance consisting of proteoglycans such as hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate,[21] as well as non-collagenous proteins such as osteocalcin, osteopontin or bone sialoprotein. Collagen consists of strands of repeating units, which give bone tensile strength, and are arranged in an overlapping fashion that prevents shear stress. The function of ground substance is not fully known.[21] Two types of bone can be identified microscopically according to the arrangement of collagen: woven and lamellar.

- Woven bone (also known as fibrous bone), which is characterized by a haphazard organization of collagen fibers and is mechanically weak.[22]

- Lamellar bone, which has a regular parallel alignment of collagen into sheets ("lamellae") and is mechanically strong.[22]

Woven bone is produced when osteoblasts produce osteoid rapidly, which occurs initially in all fetal bones, but is later replaced by more resilient lamellar bone. In adults woven bone is created after fractures or in Paget's disease. Woven bone is weaker, with a smaller number of randomly oriented collagen fibers, but forms quickly; it is for this appearance of the fibrous matrix that the bone is termed woven. It is soon replaced by lamellar bone, which is highly organized in concentric sheets with a much lower proportion of osteocytes to surrounding tissue. Lamellar bone, which makes its first appearance in humans in the fetus during the third trimester,[23] is stronger and filled with many collagen fibers parallel to other fibers in the same layer (these parallel columns are called osteons). In cross-section, the fibers run in opposite directions in alternating layers, much like in plywood, assisting in the bone's ability to resist torsion forces. After a fracture, woven bone forms initially and is gradually replaced by lamellar bone during a process known as "bony substitution." Compared to woven bone, lamellar bone formation takes place more slowly. The orderly deposition of collagen fibers restricts the formation of osteoid to about 1 to 2 µm per day. Lamellar bone also requires a relatively flat surface to lay the collagen fibers in parallel or concentric layers.[24]

Deposition

The extracellular matrix of bone is laid down by osteoblasts, which secrete both collagen and ground substance. These synthesise collagen within the cell, and then secrete collagen fibrils. The collagen fibers rapidly polymerise to form collagen strands. At this stage they are not yet mineralised, and are called "osteoid". Around the strands calcium and phosphate precipitate on the surface of these strands, within days to weeks becoming crystals of hydroxyapatite.[21]

In order to mineralise the bone, the osteoblasts secrete vesicles containing alkaline phosphatase. This cleaves the phosphate groups and acts as the foci for calcium and phosphate deposition. The vesicles then rupture and act as a centre for crystals to grow on. More particularly, bone mineral is formed from globular and plate structures.[25][26]

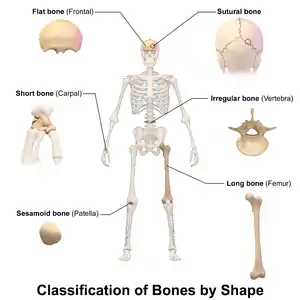

Types

There are five types of bones in the human body: long, short, flat, irregular, and sesamoid.[27]

- Long bones are characterized by a shaft, the diaphysis, that is much longer than its width; and by an epiphysis, a rounded head at each end of the shaft. They are made up mostly of compact bone, with lesser amounts of marrow, located within the medullary cavity, and areas of spongy, cancellous bone at the ends of the bones.[28] Most bones of the limbs, including those of the fingers and toes, are long bones. The exceptions are the eight carpal bones of the wrist, the seven articulating tarsal bones of the ankle and the sesamoid bone of the kneecap. Long bones such as the clavicle, that have a differently shaped shaft or ends are also called modified long bones.

- Short bones are roughly cube-shaped, and have only a thin layer of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. The bones of the wrist and ankle are short bones.

- Flat bones are thin and generally curved, with two parallel layers of compact bones sandwiching a layer of spongy bone. Most of the bones of the skull are flat bones, as is the sternum.[29]

- Sesamoid bones are bones embedded in tendons. Since they act to hold the tendon further away from the joint, the angle of the tendon is increased and thus the leverage of the muscle is increased. Examples of sesamoid bones are the patella and the pisiform.[30]

- Irregular bones do not fit into the above categories. They consist of thin layers of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. As implied by the name, their shapes are irregular and complicated. Often this irregular shape is due to their many centers of ossification or because they contain bony sinuses. The bones of the spine, pelvis, and some bones of the skull are irregular bones. Examples include the ethmoid and sphenoid bones.[31]

Terminology

In the study of anatomy, anatomists use a number of anatomical terms to describe the appearance, shape and function of bones. Other anatomical terms are also used to describe the location of bones. Like other anatomical terms, many of these derive from Latin and Greek. Some anatomists still use Latin to refer to bones. The term "osseous", and the prefix "osteo-", referring to things related to bone, are still used commonly today.

Some examples of terms used to describe bones include the term "foramen" to describe a hole through which something passes, and a "canal" or "meatus" to describe a tunnel-like structure. A protrusion from a bone can be called a number of terms, including a "condyle", "crest", "spine", "eminence", "tubercle" or "tuberosity", depending on the protrusion's shape and location. In general, long bones are said to have a "head", "neck", and "body".

When two bones join together, they are said to "articulate". If the two bones have a fibrous connection and are relatively immobile, then the joint is called a "suture".

Development

.jpg.webp)

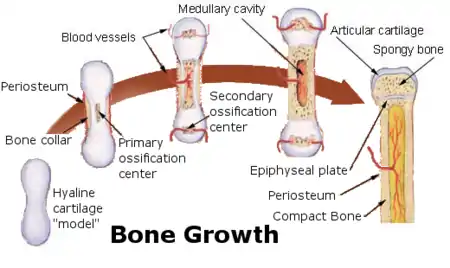

The formation of bone is called ossification. During the fetal stage of development this occurs by two processes: intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification.[32] Intramembranous ossification involves the formation of bone from connective tissue whereas endochondral ossification involves the formation of bone from cartilage.

Intramembranous ossification mainly occurs during formation of the flat bones of the skull but also the mandible, maxilla, and clavicles; the bone is formed from connective tissue such as mesenchyme tissue rather than from cartilage. The process includes: the development of the ossification center, calcification, trabeculae formation and the development of the periosteum.[33]

Endochondral ossification occurs in long bones and most other bones in the body; it involves the development of bone from cartilage. This process includes the development of a cartilage model, its growth and development, development of the primary and secondary ossification centers, and the formation of articular cartilage and the epiphyseal plates.[34]

Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called "primary ossification centers." They mostly appear during fetal development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth, and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphysis and both epiphyses of a long bone are separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the epiphyseal plate). At skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), all of the cartilage is replaced by bone, fusing the diaphysis and both epiphyses together (epiphyseal closure).[35] In the upper limbs, only the diaphyses of the long bones and scapula are ossified. The epiphyses, carpal bones, coracoid process, medial border of the scapula, and acromion are still cartilaginous.[36]

The following steps are followed in the conversion of cartilage to bone:

- Zone of reserve cartilage. This region, farthest from the marrow cavity, consists of typical hyaline cartilage that as yet shows no sign of transforming into bone.[37]

- Zone of cell proliferation. A little closer to the marrow cavity, chondrocytes multiply and arrange themselves into longitudinal columns of flattened lacunae.[37]

- Zone of cell hypertrophy. Next, the chondrocytes cease to divide and begin to hypertrophy (enlarge), much like they do in the primary ossification center of the fetus. The walls of the matrix between lacunae become very thin.[37]

- Zone of calcification. Minerals are deposited in the matrix between the columns of lacunae and calcify the cartilage. These are not the permanent mineral deposits of bone, but only a temporary support for the cartilage that would otherwise soon be weakened by the breakdown of the enlarged lacunae.[37]

- Zone of bone deposition. Within each column, the walls between the lacunae break down and the chondrocytes die. This converts each column into a longitudinal channel, which is immediately invaded by blood vessels and marrow from the marrow cavity. Osteoblasts line up along the walls of these channels and begin depositing concentric lamellae of matrix, while osteoclasts dissolve the temporarily calcified cartilage.[37]

Function

| Functions of Bone |

|---|

Mechanical

|

Synthetic

|

Metabolic

|

Bones have a variety of functions:

Mechanical

Bones serve a variety of mechanical functions. Together the bones in the body form the skeleton. They provide a frame to keep the body supported, and an attachment point for skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints, which function together to generate and transfer forces so that individual body parts or the whole body can be manipulated in three-dimensional space (the interaction between bone and muscle is studied in biomechanics).

Bones protect internal organs, such as the skull protecting the brain or the ribs protecting the heart and lungs. Because of the way that bone is formed, bone has a high compressive strength of about 170 MPa (1,700 kgf/cm2),[5] poor tensile strength of 104–121 MPa, and a very low shear stress strength (51.6 MPa).[38][39] This means that bone resists pushing (compressional) stress well, resist pulling (tensional) stress less well, but only poorly resists shear stress (such as due to torsional loads). While bone is essentially brittle, bone does have a significant degree of elasticity, contributed chiefly by collagen.

Mechanically, bones also have a special role in hearing. The ossicles are three small bones in the middle ear which are involved in sound transduction.

Synthetic

The cancellous part of bones contain bone marrow. Bone marrow produces blood cells in a process called hematopoiesis.[40] Blood cells that are created in bone marrow include red blood cells, platelets and white blood cells.[41] Progenitor cells such as the hematopoietic stem cell divide in a process called mitosis to produce precursor cells. These include precursors which eventually give rise to white blood cells, and erythroblasts which give rise to red blood cells.[42] Unlike red and white blood cells, created by mitosis, platelets are shed from very large cells called megakaryocytes.[43] This process of progressive differentiation occurs within the bone marrow. After the cells are matured, they enter the circulation.[44] Every day, over 2.5 billion red blood cells and platelets, and 50–100 billion granulocytes are produced in this way.[14]

As well as creating cells, bone marrow is also one of the major sites where defective or aged red blood cells are destroyed.[14]

Metabolic

- Mineral storage – bones act as reserves of minerals important for the body, most notably calcium and phosphorus.[45][46]

Determined by the species, age, and the type of bone, bone cells make up to 15 percent of the bone. Growth factor storage—mineralized bone matrix stores important growth factors such as insulin-like growth factors, transforming growth factor, bone morphogenetic proteins and others.[47]

- Fat storage – marrow adipose tissue (MAT) acts as a storage reserve of fatty acids.[48]

- Acid-base balance – bone buffers the blood against excessive pH changes by absorbing or releasing alkaline salts.[49]

- Detoxification – bone tissues can also store heavy metals and other foreign elements, removing them from the blood and reducing their effects on other tissues. These can later be gradually released for excretion.[50]

- Endocrine organ – bone controls phosphate metabolism by releasing fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), which acts on kidneys to reduce phosphate reabsorption. Bone cells also release a hormone called osteocalcin, which contributes to the regulation of blood sugar (glucose) and fat deposition. Osteocalcin increases both the insulin secretion and sensitivity, in addition to boosting the number of insulin-producing cells and reducing stores of fat.[51]

- Calcium balance – the process of bone resorption by the osteoclasts releases stored calcium into the systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, removing it from the bloodstream, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations.[52]

Remodeling

Bone is constantly being created and replaced in a process known as remodeling. This ongoing turnover of bone is a process of resorption followed by replacement of bone with little change in shape. This is accomplished through osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Cells are stimulated by a variety of signals, and together referred to as a remodeling unit. Approximately 10% of the skeletal mass of an adult is remodelled each year.[53] The purpose of remodeling is to regulate calcium homeostasis, repair microdamaged bones from everyday stress, and to shape the skeleton during growth.[54] Repeated stress, such as weight-bearing exercise or bone healing, results in the bone thickening at the points of maximum stress (Wolff's law). It has been hypothesized that this is a result of bone's piezoelectric properties, which cause bone to generate small electrical potentials under stress.[55]

The action of osteoblasts and osteoclasts are controlled by a number of chemical enzymes that either promote or inhibit the activity of the bone remodeling cells, controlling the rate at which bone is made, destroyed, or changed in shape. The cells also use paracrine signalling to control the activity of each other.[56][57] For example, the rate at which osteoclasts resorb bone is inhibited by calcitonin and osteoprotegerin. Calcitonin is produced by parafollicular cells in the thyroid gland, and can bind to receptors on osteoclasts to directly inhibit osteoclast activity. Osteoprotegerin is secreted by osteoblasts and is able to bind RANK-L, inhibiting osteoclast stimulation.[58]

Osteoblasts can also be stimulated to increase bone mass through increased secretion of osteoid and by inhibiting the ability of osteoclasts to break down osseous tissue. Increased secretion of osteoid is stimulated by the secretion of growth hormone by the pituitary, thyroid hormone and the sex hormones (estrogens and androgens). These hormones also promote increased secretion of osteoprotegerin.[58] Osteoblasts can also be induced to secrete a number of cytokines that promote reabsorption of bone by stimulating osteoclast activity and differentiation from progenitor cells. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and stimulation from osteocytes induce osteoblasts to increase secretion of RANK-ligand and interleukin 6, which cytokines then stimulate increased reabsorption of bone by osteoclasts. These same compounds also increase secretion of macrophage colony-stimulating factor by osteoblasts, which promotes the differentiation of progenitor cells into osteoclasts, and decrease secretion of osteoprotegerin.

Bone volume

Bone volume is determined by the rates of bone formation and bone resorption. Recent research has suggested that certain growth factors may work to locally alter bone formation by increasing osteoblast activity. Numerous bone-derived growth factors have been isolated and classified via bone cultures. These factors include insulin-like growth factors I and II, transforming growth factor-beta, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and bone morphogenetic proteins.[59] Evidence suggests that bone cells produce growth factors for extracellular storage in the bone matrix. The release of these growth factors from the bone matrix could cause the proliferation of osteoblast precursors. Essentially, bone growth factors may act as potential determinants of local bone formation.[59] Research has suggested that cancellous bone volume in postmenopausal osteoporosis may be determined by the relationship between the total bone forming surface and the percent of surface resorption.[60]

Clinical significance

A number of diseases can affect bone, including arthritis, fractures, infections, osteoporosis and tumours. Conditions relating to bone can be managed by a variety of doctors, including rheumatologists for joints, and orthopedic surgeons, who may conduct surgery to fix broken bones. Other doctors, such as rehabilitation specialists may be involved in recovery, radiologists in interpreting the findings on imaging, and pathologists in investigating the cause of the disease, and family doctors may play a role in preventing complications of bone disease such as osteoporosis.

When a doctor sees a patient, a history and exam will be taken. Bones are then often imaged, called radiography. This might include ultrasound X-ray, CT scan, MRI scan and other imaging such as a Bone scan, which may be used to investigate cancer.[61] Other tests such as a blood test for autoimmune markers may be taken, or a synovial fluid aspirate may be taken.[61]

Fractures

In normal bone, fractures occur when there is significant force applied, or repetitive trauma over a long time. Fractures can also occur when a bone is weakened, such as with osteoporosis, or when there is a structural problem, such as when the bone remodels excessively (such as Paget's disease) or is the site of the growth of cancer.[62] Common fractures include wrist fractures and hip fractures, associated with osteoporosis, vertebral fractures associated with high-energy trauma and cancer, and fractures of long-bones. Not all fractures are painful.[62] When serious, depending on the fractures type and location, complications may include flail chest, compartment syndromes or fat embolism. Compound fractures involve the bone's penetration through the skin. Some complex fractures can be treated by the use of bone grafting procedures that replace missing bone portions.

Fractures and their underlying causes can be investigated by X-rays, CT scans and MRIs.[62] Fractures are described by their location and shape, and several classification systems exist, depending on the location of the fracture. A common long bone fracture in children is a Salter–Harris fracture.[63] When fractures are managed, pain relief is often given, and the fractured area is often immobilised. This is to promote bone healing. In addition, surgical measures such as internal fixation may be used. Because of the immobilisation, people with fractures are often advised to undergo rehabilitation.[62]

Tumours

There are several types of tumour that can affect bone; examples of benign bone tumours include osteoma, osteoid osteoma, osteochondroma, osteoblastoma, enchondroma, giant cell tumour of bone, and aneurysmal bone cyst.[64]

Cancer

Cancer can arise in bone tissue, and bones are also a common site for other cancers to spread (metastasise) to.[65] Cancers that arise in bone are called "primary" cancers, although such cancers are rare.[65] Metastases within bone are "secondary" cancers, with the most common being breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, and kidney cancer.[65] Secondary cancers that affect bone can either destroy bone (called a "lytic" cancer) or create bone (a "sclerotic" cancer). Cancers of the bone marrow inside the bone can also affect bone tissue, examples including leukemia and multiple myeloma. Bone may also be affected by cancers in other parts of the body. Cancers in other parts of the body may release parathyroid hormone or parathyroid hormone-related peptide. This increases bone reabsorption, and can lead to bone fractures.

Bone tissue that is destroyed or altered as a result of cancers is distorted, weakened, and more prone to fracture. This may lead to compression of the spinal cord, destruction of the marrow resulting in bruising, bleeding and immunosuppression, and is one cause of bone pain. If the cancer is metastatic, then there might be other symptoms depending on the site of the original cancer. Some bone cancers can also be felt.

Cancers of the bone are managed according to their type, their stage, prognosis, and what symptoms they cause. Many primary cancers of bone are treated with radiotherapy. Cancers of bone marrow may be treated with chemotherapy, and other forms of targeted therapy such as immunotherapy may be used.[66] Palliative care, which focuses on maximising a person's quality of life, may play a role in management, particularly if the likelihood of survival within five years is poor.

Painful conditions

- Osteomyelitis is inflammation of the bone or bone marrow due to bacterial infection.

- Osteomalacia is a painful softening of adult bone caused by severe vitamin D deficiency.

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Osteochondritis dissecans

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Skeletal fluorosis is a bone disease caused by an excessive accumulation of fluoride in the bones. In advanced cases, skeletal fluorosis damages bones and joints and is painful.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease of bone where there is reduced bone mineral density, increasing the likelihood of fractures.[67] Osteoporosis is defined in women by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density of 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass, relative to the age and sex-matched average. This density is measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), with the term "established osteoporosis" including the presence of a fragility fracture.[68] Osteoporosis is most common in women after menopause, when it is called "postmenopausal osteoporosis", but may develop in men and premenopausal women in the presence of particular hormonal disorders and other chronic diseases or as a result of smoking and medications, specifically glucocorticoids.[67] Osteoporosis usually has no symptoms until a fracture occurs.[67] For this reason, DEXA scans are often done in people with one or more risk factors, who have developed osteoporosis and are at risk of fracture.[67]

Osteoporosis treatment includes advice to stop smoking, decrease alcohol consumption, exercise regularly, and have a healthy diet. Calcium and trace mineral supplements may also be advised, as may Vitamin D. When medication is used, it may include bisphosphonates, Strontium ranelate, and hormone replacement therapy.[69]

Osteopathic medicine

Osteopathic medicine is a school of medical thought originally developed based on the idea of the link between the musculoskeletal system and overall health, but now very similar to mainstream medicine. As of 2012, over 77,000 physicians in the United States are trained in osteopathic medical schools.[70]

Osteology

The study of bones and teeth is referred to as osteology. It is frequently used in anthropology, archeology and forensic science for a variety of tasks. This can include determining the nutritional, health, age or injury status of the individual the bones were taken from. Preparing fleshed bones for these types of studies can involve the process of maceration.

Typically anthropologists and archeologists study bone tools made by Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis. Bones can serve a number of uses such as projectile points or artistic pigments, and can also be made from external bones such as antlers.

Other animals

Bird skeletons are very lightweight. Their bones are smaller and thinner, to aid flight. Among mammals, bats come closest to birds in terms of bone density, suggesting that small dense bones are a flight adaptation. Many bird bones have little marrow due to their being hollow.[71]

A bird's beak is primarily made of bone as projections of the mandibles which are covered in keratin.

A deer's antlers are composed of bone which is an unusual example of bone being outside the skin of the animal once the velvet is shed.[72]

The extinct predatory fish Dunkleosteus had sharp edges of hard exposed bone along its jaws.[73][74]

Many animals possess an exoskeleton that is not made of bone. These include insects and crustaceans.

The proportion of cortical bone that is 80% in the human skeleton may be much lower in other animals, especially in marine mammals and marine turtles, or in various Mesozoic marine reptiles, such as ichthyosaurs,[75] among others.[76]

Many animals, particularly herbivores, practice osteophagy—the eating of bones. This is presumably carried out in order to replenish lacking phosphate.

Many bone diseases that affect humans also affect other vertebrates—an example of one disorder is skeletal fluorosis.

Society and culture

Bones from slaughtered animals have a number of uses. In prehistoric times, they have been used for making bone tools.[77] They have further been used in bone carving, already important in prehistoric art, and also in modern time as crafting materials for buttons, beads, handles, bobbins, calculation aids, head nuts, dice, poker chips, pick-up sticks, ornaments, etc. A special genre is scrimshaw.

Bone glue can be made by prolonged boiling of ground or cracked bones, followed by filtering and evaporation to thicken the resulting fluid. Historically once important, bone glue and other animal glues today have only a few specialized uses, such as in antiques restoration. Essentially the same process, with further refinement, thickening and drying, is used to make gelatin.

Broth is made by simmering several ingredients for a long time, traditionally including bones.

Bone char, a porous, black, granular material primarily used for filtration and also as a black pigment, is produced by charring mammal bones.

Oracle bone script was a writing system used in Ancient China based on inscriptions in bones. Its name originates from oracle bones, which were mainly ox clavicle. The Ancient Chinese (mainly in the Shang dynasty), would write their questions on the oracle bone, and burn the bone, and where the bone cracked would be the answer for the questions.

To point the bone at someone is considered bad luck in some cultures, such as Australian aborigines, such as by the Kurdaitcha.

The wishbones of fowl have been used for divination, and are still customarily used in a tradition to determine which one of two people pulling on either prong of the bone may make a wish.

Various cultures throughout history have adopted the custom of shaping an infant's head by the practice of artificial cranial deformation. A widely practised custom in China was that of foot binding to limit the normal growth of the foot.

Additional images

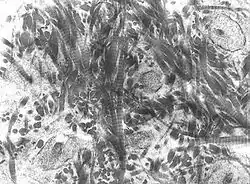

Cells in bone marrow

Cells in bone marrow Scanning electron microscope of bone at 100× magnification

Scanning electron microscope of bone at 100× magnification Structure detail of an animal bone

Structure detail of an animal bone

See also

References

- Steele, D. Gentry; Claud A. Bramblett (1988). The Anatomy and Biology of the Human Skeleton. Texas A&M University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-89096-300-5.

- Mammal anatomy : an illustrated guide. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 2010. p. 129. ISBN 9780761478829.

- "ossein". The Free Dictionary.

- Hall, John (2011). Textbook of Medical Physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 957–960. ISBN 978-08089-2400-5.

- Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1984). Scaling: Why Is Animal Size So Important?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-31987-4.

- "CK12-Foundation". flexbooks.ck12.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Deakin 2006, p. 192.

- Gdyczynski, C.M.; Manbachi, A.; et al. (2014). "On estimating the directionality distribution in pedicle trabecular bone from micro-CT images". Journal of Physiological Measurements. 35 (12): 2415–2428. Bibcode:2014PhyM...35.2415G. doi:10.1088/0967-3334/35/12/2415. PMID 25391037.

- Deakin 2006, p. 195.

- Hall, Susan J. (2007). Basic Biomechanics with OLC (5th ed., Revised. ed.). Burr Ridge: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-07-126041-1.

- Gomez, Santiago (February 2002). "Crisóstomo Martinez, 1638-1694: the discoverer of trabecular bone". Endocrine. 17 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1385/ENDO:17:1:03. ISSN 1355-008X. PMID 12014701. S2CID 46340228.

- Barnes-Svarney, Patricia L.; Svarney, Thomas E. (2016). The Handy Anatomy Answer Book : Includes Physiology. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9781578595426.

- Deakin 2006, p. 189.

- Deakin 2006, p. 58.

- Deakin 2006, pp. 189–190.

- Washington. "The O' Cells." Bone Cells. University of Washington, n.d. Web. 3 Apr. 2013.

- Davis, Michael. "DrTummy.com | DrTummy.com." DrTummy.com | DrTummy.com. Dr. Tummy, n.d. Web. 3 Apr. 2013.

- Sims, Natalie A.; Vrahnas, Christina (2014). "Regulation of cortical and trabecular bone mass by communication between osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 561: 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.015. PMID 24875146.

- Deakin 2006, p. 190.

- Enhancement of Hydroxyapatite Dissolution Journal of Materials Science & Technology,38, 148-158

- Hall 2005, p. 981.

- Currey, John D. (2002). "The Structure of Bone Tissue", pp. 12–14 in Bones: Structure and Mechanics. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. ISBN 9781400849505

- Salentijn, L. Biology of Mineralized Tissues: Cartilage and Bone, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine post-graduate dental lecture series, 2007

- Royce, Peter M.; Steinmann, Beat (14 April 2003). Connective Tissue and Its Heritable Disorders: Molecular, Genetic, and Medical Aspects. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-46117-3.

- Bertazzo, S.; Bertran, C. A. (2006). "Morphological and dimensional characteristics of bone mineral crystals". Bioceramics. 309–311 (Pt. 1, 2): 3–10. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.309-311.3. S2CID 136883011.

- Bertazzo, S.; Bertran, C.A.; Camilli, J.A. (2006). "Morphological Characterization of Femur and Parietal Bone Mineral of Rats at Different Ages". Key Engineering Materials. 309–311: 11–14. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.309-311.11. S2CID 135813389.

- "Types of bone". mananatomy.com. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "DoITPoMS - TLP Library Structure of bone and implant materials - Structure and composition of bone". www.doitpoms.ac.uk.

- Bart Clarke (2008), "Normal Bone Anatomy and Physiology", Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3 (Suppl 3): S131–S139, doi:10.2215/CJN.04151206, PMC 3152283, PMID 18988698

- Adriana Jerez; Susana Mangione; Virginia Abdala (2010), "Occurrence and distribution of sesamoid bones in squamates: a comparative approach", Acta Zoologica, 91 (3): 295–305, doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2009.00408.x

- Pratt, Rebecca. "Bone as an Organ". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- OpenStax, Anatomy & Physiology. OpenStax CNX. Feb 26, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@8.24

- "Bone Growth and Development | Biology for Majors II". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (15 May 2018). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-44445-9.

- "6.4B: Postnatal Bone Growth". Medicine LibreTexts. 19 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Agur, Anne (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- Saladin, Kenneth (2012). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- Vincent, Kevin. "Topic 3: Structure and Mechanical Properties of Bone". BENG 112A Biomechanics, Winter Quarter, 2013. Department of Bioengineering, University of California.

- Turner, C.H.; Wang, T.; Burr, D.B. (2001). "Shear Strength and Fatigue Properties of Human Cortical Bone Determined from Pure Shear Tests". Calcified Tissue International. 69 (6): 373–378. doi:10.1007/s00223-001-1006-1. PMID 11800235. S2CID 30348345.

- Fernández, KS; de Alarcón, PA (December 2013). "Development of the hematopoietic system and disorders of hematopoiesis that present during infancy and early childhood". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 60 (6): 1273–89. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2013.08.002. PMID 24237971.

- Deakin 2006, p. 60-61.

- Deakin 2006, p. 60.

- Deakin 2006, p. 57.

- Deakin 2006, p. 46.

- Doyle, Máire E.; Jan de Beur, Suzanne M. (2008). "The Skeleton: Endocrine Regulator of Phosphate Homeostasis". Current Osteoporosis Reports. 6 (4): 134–141. doi:10.1007/s11914-008-0024-6. PMID 19032923. S2CID 23298442.

- Walker, Kristin. "Bone". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Pv, Hauschka; Tl, Chen; Ae, Mavrakos (1988). "Polypeptide Growth Factors in Bone Matrix". Ciba Foundation Symposium. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 136: 207–25. doi:10.1002/9780470513637.ch13. ISBN 9780470513637. PMID 3068010. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Styner, Maya; Pagnotti, Gabriel M; McGrath, Cody; Wu, Xin; Sen, Buer; Uzer, Gunes; Xie, Zhihui; Zong, Xiaopeng; Styner, Martin A (1 May 2017). "Exercise Decreases Marrow Adipose Tissue Through ß-Oxidation in Obese Running Mice". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 32 (8): 1692–1702. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3159. ISSN 1523-4681. PMC 5550355. PMID 28436105.

- Fogelman, Ignac; Gnanasegaran, Gopinath; Wall, Hans van der (3 January 2013). Radionuclide and Hybrid Bone Imaging. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-02400-9.

- "Bone". flipper.diff.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Lee, Na Kyung; et al. (10 August 2007). "Endocrine Regulation of Energy Metabolism by the Skeleton". Cell. 130 (3): 456–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. PMC 2013746. PMID 17693256.

- Foundation, CK-12. "Bones". www.ck12.org. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Manolagas, SC (April 2000). "Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis". Endocrine Reviews. 21 (2): 115–37. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395. PMID 10782361.

- Hadjidakis DJ, Androulakis II (31 January 2007). "Bone remodeling". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1092: 385–96. doi:10.1196/annals.1365.035. PMID 17308163. S2CID 39878618. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ed, Russell T. Woodburne ..., consulting (1999). Anatomy, physiology, and metabolic disorders (5. print. ed.). Summit, N.J.: Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp. pp. 187–189. ISBN 978-0-914168-88-1.

- Fogelman, Ignac; Gnanasegaran, Gopinath; Wall, Hans van der (3 January 2013). Radionuclide and Hybrid Bone Imaging. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-02400-9.

- "Introduction to cell signaling (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- Boulpaep, Emile L.; Boron, Walter F. (2005). Medical physiology: a cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 1089–1091. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- Baylink, D. J. (1991). "Bone growth factors". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (263): 30–48. doi:10.1097/00003086-199102000-00004. PMID 1993386.

- Nordin, BE; Aaron, J; Speed, R; Crilly, RG (8 August 1981). "Bone formation and resorption as the determinants of trabecular bone volume in postmenopausal osteoporosis". Lancet. 2 (8241): 277–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)90526-2. PMID 6114324. S2CID 29646037.

- Britton 2010, pp. 1059–1062.

- Britton 2010, pp. 1068.

- Salter RB, Harris WR (1963). "Injuries Involving the Epiphyseal Plate". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 45 (3): 587–622. doi:10.2106/00004623-196345030-00019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- "Benign Bone Tumours". Cleveland Clinic. 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Britton 2010, pp. 1125.

- Britton 2010, pp. 1032.

- Britton 2010, pp. 1116–1121.

- WHO (1994). "Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group". World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 843: 1–129. PMID 7941614.

- Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1116–1121. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- "2012 OSTEOPATHIC MEDICAL PROFESSION REPORT" (PDF). Osteopathic.org. American Osteopathic Organisation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Dumont, E. R. (17 March 2010). "Bone density and the lightweight skeletons of birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1691): 2193–2198. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0117. PMC 2880151. PMID 20236981.

- Hans J. Rolf; Alfred Enderle (1999). "Hard fallow deer antler: a living bone till antler casting?". The Anatomical Record. 255 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990501)255:1<69::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-R. PMID 10321994.

- "Dunkleosteus". American Museum of Natural History.

- cmnh.org

- de Buffrénil V.; Mazin J.-M. (1990). "Bone histology of the ichthyosaurs: comparative data and functional interpretation". Paleobiology. 16 (4): 435–447. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010174. JSTOR 2400968.

- Laurin, M.; Canoville, A.; Germain, D. (2011). "Bone microanatomy and lifestyle: a descriptive approach". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 10 (5–6): 381–402. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.02.003.

- Laszlovszky, J¢zsef; Szab¢, P‚ter (1 January 2003). People and Nature in Historical Perspective. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-86-2.

Footnotes

- Katja Hoehn; Marieb, Elaine Nicpon (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-5909-1.

- Bryan H. Derrickson; Tortora, Gerard J. (2005). Principles of anatomy and physiology. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-68934-8.

- Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- Deakin, Barbara Young; et al. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas (5th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-068-508. – drawings by Philip J.

- Hall, Arthur C.; Guyton, John E. (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- Anthony, S. Fauci; Harrison, T.R.; et al. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York [etc.]: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147692-8. – Anthony edits the current version; Harrison edited previous versions.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bones. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bone |

- Educational resource materials (including animations) by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research

- Review (including references) of piezoelectricity and bone remodelling

- A good basic overview of bone biology from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Usha Kini; B. N. Nandeesh (3 January 2013). "Ch 2: Physiology of Bone Formation, Remodeling, and Metabolism" (PDF). In Ignac Fogelman; Gopinath Gnanasegaran; Hans van der Wall (eds.). Radionuclide and hybrid bone imaging. Berlin: Springer. pp. 29–57. ISBN 978-3-642-02399-6.

- Bone histology photomicrographs