St. Audoen's Church, Dublin (Church of Ireland)

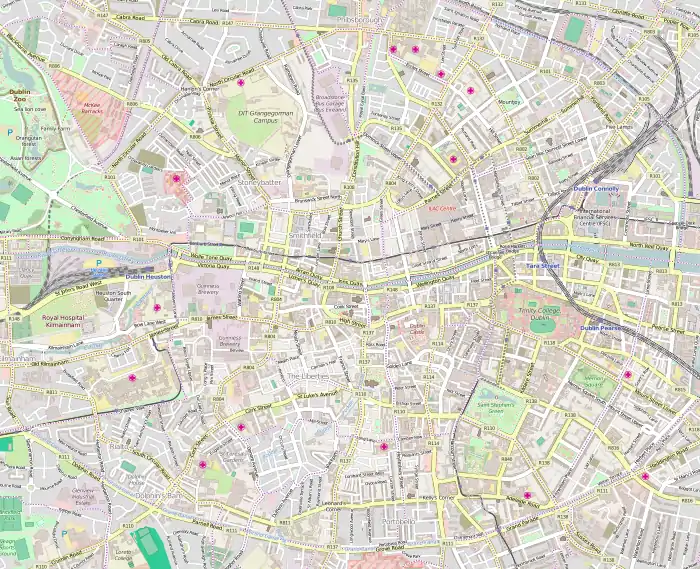

St Audoen's Church (/ˈɔːdən/) is the church of the parish of Saint Audoen in the Church of Ireland, located south of the River Liffey at Cornmarket in Dublin, Ireland. This was close to the centre of the medieval city. The parish is in the Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough. St Audoen's is the oldest parish church in Dublin and still used as such. There is a Roman Catholic church of the same name adjacent to it.

| St Audoen's Church | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

St Audoen's Church | |

| Location | Cornmarket, Dublin |

| Country | Ireland |

| Denomination | Church of Ireland |

| Website | http://cja.dublin.anglican.org/ |

| History | |

| Founded | 1190 |

| Founder(s) | John Comyn |

| Dedication | Audoen (bishop) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | St Catherine and St James with St Audoen |

| Diocese | Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough |

| Province | Province of Dublin (Church of Ireland) |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Rev. Canon Mark Gardner |

Church

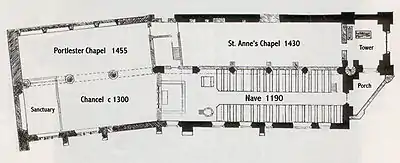

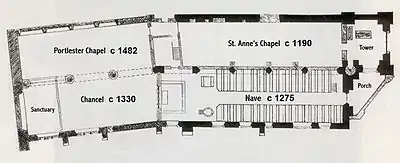

The church is named after St Ouen (or Audoen) of Rouen (Normandy), a saint who lived in the seventh century and was dedicated to him by the Anglo-Normans, who arrived in Dublin after 1172. It was erected in 1190, possibly on the site of an older church dedicated to St. Columcille, dating to the seventh century. Shortly afterwards the nave was lengthened (but also made narrower) and a century later a chancel was added.

In 1430 Henry VI, Lord of Ireland, authorised the erection of a chantry here, to be dedicated to St Anne. Its founders and successors were to be called the Guild or Fraternity of St Anne, usually called Saint Anne's Guild. Six separate altars were set up in this chapel and were in constant use, financed by the wealthier parishioners. In 1485 Sir Roland Fitz-Eustace, Earl Portlester, erected a new chapel next to the nave, in gratitude for his preservation from shipwreck near the site.[1]

The turbulent events of the 16th century had its effects on the upkeep of the church and in 1630 the church was declared to be in a decrepit state. The Archbishop, Lancelot Bulkeley, complained that "there is a guild there called St Anne's Guild that hath swallowed upp all the church meanes" (although chantries and guilds were suppressed during the Reformation in England and their property taken over by the king, in Ireland they survived, with varying vicissitudes, for many years).[2]

Strenuous efforts were made over the next few years to repair the roof, steeple and pillars of the building, and the guild was ordered to contribute its share. Funds were low – there were only sixteen Protestant houses in the parish. In 1671 Michael Boyle, the Church of Ireland Primate, ordered the "annoyance of the buttermilke market" under St Audoen's to be closed.[3] In 1673 an order was made to remove the tombs and tombstones from the church "to preserve the living from being injured by the dead".[4] St Anne's Guild, which had managed to secret away its extensive properties after the Reformation, and which had remained under Roman Catholic control, never did give up its holdings, despite several investigations and court orders lasting until 1702.[4]

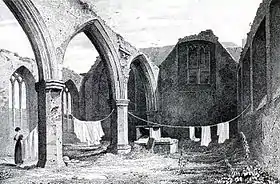

Although many repairs were carried out to the church and tower over the centuries, finance for the maintenance of the structures was always a problem, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. By 1825, the church building itself was in a ruinous state (as reported by G. N. Wright) and "very few Protestants" remained in the parish.[5] As the finance to carry out substantial repairs was not available, parts of the church were closed off or unroofed. As a consequence many ancient tombs gradually crumbled and memorials were removed or rendered illegible by exposure to the weather.

Parish

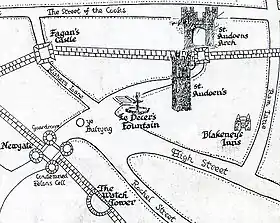

St Audoen's parish was once the wealthiest within the city and the church was for hundreds of years frequented on State occasions by the Lord Mayor and Corporation.[3] In its heyday, the church was closely connected with the Guilds of the city and "was accounted the best in Dublin for the greater number of Aldermen and Worships of the city living in the Parish" (Richard Stanihurst, 1568). The Tanners' Guild was located in the tower and the Bakers' Guild (Saint Anne's Guild) in a "college" adjoining the church.[6]

In 1467 St Audoen's was made a prebendary of St. Patrick's Cathedral by Archbishop Michael Tregury.[7]

In July 1536 George Browne arrived in Ireland as Archbishop of Dublin, and a few years later he energetically pushed through the wishes of Henry VIII to be recognized as supreme head of the Irish church. About 1544 the vicar of St Audoen's became the nominee of the Crown. In 1547 the assets of the parish were appropriated by the state church that was established following the English Reformation (more particularly the Tudor conquest of Ireland).[8]

Queen Mary I, soon after her accession in 1553, restored by Charter the Cathedral of St. Patrick. The Prebendary of St Audoen named in this Charter of Restoration was, in 1555, Robert Daly. However, when Queen Elizabeth I ascended the throne she nominated him Bishop of Kildare. From then on, all Roman Catholic ceremonies in the church ceased.[9]

After the Reformation the majority of parishioners remained loyal to the Roman Catholic church, and in 1615 a new Roman Catholic parish of St Audoen's was established.[10] However the Catholics were obliged to hold their services in secret, mainly in nearby Cook Street. Later in the century celebration of Mass was forbidden and bishops and priests deported, imprisoned or executed. This troubled period for Catholics lasted until the beginning of the 19th century.[11] Meanwhile, the now Protestant church and parish of St Audoen had to struggle through the seventeenth century and began to decline.[12] Towards the end of the eighteenth century, following a trend in several inner-city parishes, many of the wealthy parish residents moved out to the suburbs, a process that was hastened by the Act of Union.[13][14] Poor Catholics then moved into the houses thus vacated, which were turned into tenements.[15][16]

In 1813 the population of the parish was 1,993 males and 2,674 females, the majority of whom were Roman Catholics.[17]

Restoration

The architect Thomas Drew was the first to draw serious attention to the importance of the church, architecturally and historically, in 1866. He produced detailed plans of the church for which he won an award from the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland, carried out excavations and drew up a paper on the church and its history. In a booklet published in 1873 the rector Alexander Leeper urged reroofing and restoration of the church.

In the 1980s an extensive restoration of the tower and bells was carried out. A few years later St Anne's chapel, which had lost its roof and many monuments, was re-roofed and converted to a visitor reception centre, which included an exhibition on the history of the church.[18]

During conservation works starting in 1996 an extensive excavation of a small section of the church was carried out, which cast new light on the early days of the church. This contributed greatly to an understanding of the building history of the church. The detailed results of this study were published in book form in 2006.[18]

Memorials

In the main porch is stored an early Celtic gravestone known as the Lucky Stone which has been kept here or hereabouts since before 1309. It was said to have strange properties, and merchants and traders used to rub it for luck. It was first mentioned when Jon Le Decer, Mayor of Dublin, erected a marble cistern for water in Cornmarket in 1309 and placed this stone against it, so that all who drank of the waters may have luck. The stone was stolen on a number of occasions but always found its way back this neighbourhood. In 1826 it disappeared for twenty years, until found in front of the newly erected Catholic Church in High Street.[3]

In the porch of the western door lie the fifteenth-century monuments of Sir Roland Fitz-Eustace, Lord Portlester, who died in 1496, and his wife, Margaret. Fitz-Eustace was Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, then Lord Chancellor of Ireland and finally Lord High Treasurer of Ireland. His refusal to surrender this last post led to a break with the king and almost to civil war. He was buried at Cotlandstown, County Kildare. Peter Talbot the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, who died in prison in 1680, is said to have been secretly entombed nearby. Among those buried in the church are William Molyneux, his brother Sir Thomas Molyneux and Thomas' son Capel,[5] Edward Parry, the Bishop of Killaloe and his sons John Parry and Benjamin Parry, successively Bishops of Ossory, and Lady Frances Brudenell.[19]

During excavations in the 19th century an Anglo-Norman font, dating to the 12th century, was found and is now on display in the church.

Tower

The church tower dates from the 17th century. The need to keep this structure in good repair was always a drain on parish funds. It was repaired in 1637, which was paid for by the Guild of St Anne, but in 1669 part of it collapsed onto the roof of the church, and it had to be re-built. The Guild contributed £250 towards the cost of reconstruction. In 1826 the tower was remodelled by Henry Aaron Baker but by the end of the century was again in a dangerous state. Some remedial work was carried out in 1916 after an appeal from the Archbishop of Dublin, but it was not until the major restoration of 1982 that the tower was rendered safe.[20]

The tower houses six bells, three of which are Ireland's oldest bells, dating from 1423. The bells were rung for the Angelus and after the Reformation continued to be rung every morning and evening to call the people to and from their work. Two bells in the tower were cast by John Murphy of Dublin in 1864 and 1880, and the treble was dated 1790 and came from Glasgow.[21] Due to the fragile state of the tower they were not rung between 1898 and 1983.[22] After the tower was strengthened with concrete, a major overhaul was done on the bells. Three of the bells were recast,[23] and the tenor was recast in memory of Alexander E. Donovan (1908-1982), who was closely connected with the church. They are now rung every week.[24]

The present clock on the church tower came from St Peter's Church in Aungier Street, after this church was demolished in the 1980s. The clock face dates from the 1820s.[24]

Cemetery

_(geograph_3784739).jpg.webp)

The old disused graveyard of St Audoen's has been converted into a recreation ground. Many notables were buried there, including many bishops and Lord Mayors of the city and the families of Ball, Bath, Blakeney, Browne, Cusack, Desminier, Fagan, Foster, Fyan, Gifford, Gilbert, Malone, Mapas, Molesworth, Penteny, Perceval, Quinn, Talbot and Ussher.[25] The Curate-assistant Christopher Teeling McCready (died 1913) collected detailed genealogies of some of these families in seven hand-written volumes, which are now in Marsh's Library.

Among the burials within the church and graveyard are:

- Bartholomew Ball

- Margaret Ball

- Nicholas Ball

- Lady Frances Brudenell

- John Bysse

- Adam Cusack

- Paul Davys

- Paul Davys, 1st Viscount Mount Cashell

- Sir William Davys

- Robert Molesworth, 1st Viscount Molesworth

- Sir Thomas Molyneux

- William Molyneux

- Benjamin Parry

- Edward Parry

- John Parry

- Philip Perceval

- Sir James Somerville, 1st Baronet

- Peter Talbot

Historical events

On 11 March 1597 a massive accidental gunpowder explosion in one of the nearby quays damaged the tower of St. Audoen's.

In the 1640s, at the time of the Catholic Confederate Rebellion, the burghers of the city could see from the church tower the fires of their opponents burning in the distance.

In 1733 a popular Alderman, Humphrey Frend, was returned at an election by a large majority, and two barrels of pitch were burned as celebration at the top of St. Audoen's tower.

The United Irishman Oliver Bond was elected Minister's Churchwarden of the church in 1787 (although a Presbyterian, the established church was entitled to appoint local residents for church duties).[3] Another United Irishman whose family had a long association with the church was James Napper Tandy, born at No. 5 Cornmarket and baptised (as 'James Naper Tandy') on 16 February 1739.[26] He was a Churchwarden of the church in 1765 and played a significant role in the life of the city before the Act of Union in 1801.[27]

In 1793 a petition was sent from the vestry, requesting the removal of the police on the grounds of expense and inefficiency, and for the return of the night watchman originally appointed by the parish.[3]

References and sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Audoen's Church, Cornmarket. |

- Sources

- G. N. Wright (2005). "An Historical Guide to the City of Dublin". Online 19th-century book. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- Gilbert, John (1854). A History of the City of Dublin. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Leeper, Alexander (1873). History of St. Audoen's (by the rector). Dublin.

- Dublin: Catholic Truth Society, 1911: Bishop of Canea: Short Histories of Dublin Parishes

- Ronan, Miles (1926). The Reformation in Dublin 1536-1558. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Donovan, Alex E. (1930). Dublin's Oldest Building. Dublin: St. Audoen's (pamphlet).

- Crawford, John (1986). Within the Walls: The Story of St. Audoen's Church. Dublin: Select Vestry of the St. Patrick's Cathedral Group of Parishes.

- Curtis, Joe (1992). Times, Chimes and Charms of Dublin. Dublin: Verge Books.

- F. H. A. Aalen and Kevin Whelan (editors): Dublin City and County, from Prehistory to Present. Geography Publications, Dublin, 1992. ISBN 0-906602-19-X.

- McMahon, Mary (2006). St. Audoen's Church, Cornmarket, Dublin: Archaeology and Architecture. Dublin: The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0755773152.

- Notes

- Report (18 February 1875). "Eustace Family". The Irish Times. p. 5.

- Ronan, 1926, p. 329

- Donovan (1930)

- Gilbert (1854)

- G. N. Wright

- Crawford (1986), p. 14

- Crawford (1986), p. 19

- Ronan, 1926

- Short Histories of Dublin Parishes, p. 167

- F H A Aalen and Kevin Whelan (editors) p. 243

- Gilbert (1854), p. 305 et passim

- Gilbert (1854), p. 277-286, containing reports of 1630, decree of 1633, assessment from 1636, Bishop's report from 1639, and so on to the end of the century.

- Gilbert (1854), p. 285

- "The earliest extant parochial register (1672-1803) shows a significant drop in baptisms and burials during the second half of the 18th century. By 1880, the parish served an area of Dublin where poverty and social deprivation were very much to the fore." Crawford, p. 15

- F H A Aalen and Kevin Whelan (editors) p. 239

- See census returns for this parish, 1901 Census

- Government figures quoted in M'Gregor, Picture of Dublin (1821), p. 62

- McMahon, 2006

- Gilbert (1854), p. 282

- Crawford (1986), p. 23

- MrHistorianDude (28 October 2018), Details of the bells at St. Audoen's Church, Dublin. From an information leaflet in the church., retrieved 8 February 2019

- "St Audeon Dublin - BellringingIreland.org". www.bellringingireland.org. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Dove Details". dove.cccbr.org.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Curtis (1992), p. 91

- Gilbert (1854), p. 283

- The parish record book lists the entries for January and February 1739 as '1738', apparently in clerical error.

- Crawford (1986), p. 38