St Chad's College, Durham

St Chad's College is a recognised (independent) college of Durham University in England, founded in 1904 as an Anglican hall for the training of Church of England clergy. The main part of the college is located on the Bailey, occupying nine historic buildings at the east end of Durham Cathedral. It neighbours Hatfield College to its north, while St John's College and St Cuthbert's Society are to its south. The college is named after St Chad of Mercia, a 7th-century bishop.

| St Chad's College | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Durham | ||||||||||||||||||

Main College | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

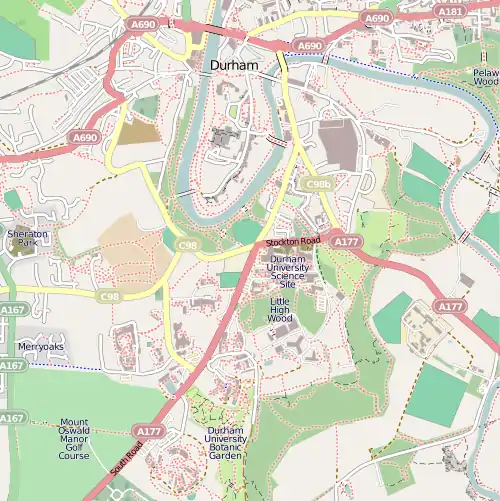

| Coordinates | 54.772925°N 1.574695°W | |||||||||||||||||

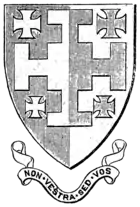

| Motto | Latin: Non vestra sed vos | |||||||||||||||||

| Motto in English | Not what you have, but who you are | |||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1904 | |||||||||||||||||

| Named for | Chad of Mercia | |||||||||||||||||

| Principal | Margaret Masson[1] | |||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 409 | |||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 150 | |||||||||||||||||

| Senior tutor | Eleanor Spencer-Regan[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| Website | stchads | |||||||||||||||||

| JCR | St Chad's JCR | |||||||||||||||||

| MCR | St Chad's MCR | |||||||||||||||||

| SCR | St Chad's SCR | |||||||||||||||||

| Boat club | St Chad's Boat Club | |||||||||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||||||||

Location in Durham, England | ||||||||||||||||||

Although it is the smallest of Durham's colleges in terms of student numbers (in 2018–19, the college had 409 undergraduates and 150 active postgraduates),[3] it has the largest staff, extensive college library facilities, and among the highest undergraduate academic results in Durham.[4]

History

St Chad's Hostel and Hall

In 1902, Frederick Samuel Willoughby, vicar of Hooton Pagnell near Doncaster, opened St Chad's Hostel to prepare men of limited financial means for entry to Church of England theological colleges. He was supported by lady of the manor Julia Warde-Aldam, who in 1903 funded a dedicated building for the hostel in Hooton Pagnell.[5]

The further financial support of Douglas Horsfall, a wealthy Liverpool businessman and devoted churchman (who also funded the building of several large Anglo-Catholic churches in his home city), made it possible in 1904 to establish a hall at Durham University as a sister institution to the Hooton Pagnell hostel, to allow students to read for university degrees alongside training for ordination. Durham University had a provision in its statutes to recognise independent colleges, permitting students to matriculate through those institutions and then to sit for Durham exams.

A licence from the university was obtained and St Chad's Hall opened in October 1904 at 1 South Bailey, Durham, with nineteen students.[6] With the expansion to Durham, Willoughby withdrew from the project and Revd Stephen Moulsdale, a Durham graduate who had been vice-principal of the hostel, became the first principal of the hall as well as principal of the hostel.[7]

The college soon expanded into neighbouring buildings, starting with 28 North Bailey (adjoining 1 South Bailey) which was rented from the Dean and Chapter. In 1909, a small wooden chapel was constructed behind the South Bailey buildings, and dedicated by the Bishop of Jarrow.[6]

The Durham hall and Hooton Pagnell hostel continued to operate in partnership, with students studying for a year at the hostel before moving to the hall to complete their studies, until 1916 when the Hooton Pagnell building was requisitioned as a war hospital and all teaching was moved to Durham. The hostel building was returned after the war, and re-opened for a short time, but the financial problems of running in two locations led to the hostel finally closing in 1921.[5]

St Chad's College

In 1918, after the college had established a number of endowed fellowships, the university recognised St Chad's as the university's second college.[7]

The college continued to expand with the lease and purchase of further buildings on the Bailey, including Douglas House at 18 North Bailey, purchased in 1925. In 1928, the current chapel (intended as a temporary building) was built behind Douglas House,[6] with the previous chapel building given to found St Chad's Church, Sunderland.[8]

In 1937, C E Whiting's centenary history of the university recorded that the college had 55 students and five staff, but could easily double its numbers if accommodation were available.[6]

Consolidation on North Bailey

In the 1960s, the college took steps to consolidate its site on North Bailey, with the houses at the junction of Bow Lane and North Bailey being demolished in 1961 to enable the construction of a new dining hall and quadrangle, designed by neo-classical architect Francis Johnson. These new buildings were joined to existing 18th century houses at 16–18 North Bailey to form the present Main College.

In 1965, the college's original home on South Bailey was exchanged with neighbouring St John's College for 22 and 22A North Bailey (now Grads House) which with other purchases gave the college a 95m-long frontage on North Bailey.[9]

Later events

The college ceased formal ordination training in 1971, but remains a Church of England foundation with students studying for degrees across all departments of the university.

St Chad's was among the last university colleges in the UK to admit women undergraduates: as a part of a co-ordinated step-change in the university, the final all-male year entered in September 1987.

The college has continued to slowly expand, with 361 students (183 living in college) in 2003, and 547 students (285 living in college) in 2018.[10] New buildings have been acquired to allow for this increase, including former Durham School boarding house Trinity Hall as postgraduate accommodation, and additional houses on North Bailey.

I have always loved Saint Chad's College and it has been a joy to see the college go from strength to strength.... My spiritual home in Durham since 1939, Saint Chad's College represents to me the wholeness of faith and practice so needed in the universities and in the nation."

Buildings

Students who study at St Chad's are accommodated in nine different houses: Queen's Court, Epiphany House, Main College, Lightfoot House, Langford House, Grads and Ramsey House and Trinity Hall all accommodate undergraduates; Hallgarth Street and Trinity Hall, along with part of Main College, are home to the college's postgraduate community.

Most of the college buildings are Grade II listed. Grade I listed 12th-century castle walls run through the college's gardens.[12]

Main College

.jpg.webp)

Main College is located at 18 North Bailey, adjacent to Bow Lane, and consists of the college dining hall (the Moulsdale Hall), designed in 1961 by neo-classical architect Francis Johnson, joined to a number of primarily 18th-century houses along North Bailey.[13]

At the centre of Main College, adjacent to the Moulsdale Hall, is the Cassidy Quad. This was originally an open quadrangle between buildings, but was given a glass roof for the college's centenary in 2004. Main College houses the college's major public areas, including the Junior and Senior Common Rooms (JCR and SCR), bar, libraries and gymnasium, and most college offices.

The college's croquet lawn, chapel and laundry are behind main college, along with walled gardens associated with the historic houses that make up the college.

A graffito on the Bow Lane side of the dining hall reads "Pulchra Semper" (Latin: always beautiful), and has been in place since at least the 1970s.[13]

Queen's Court

Queen's Court, 1 and 2 North Bailey, is located at the junction between Saddler Street, North Bailey, and Owengate. It was built in the early 19th century and contains 24 student rooms.[14][15] The college for many years occupied only 1 North Bailey, while no. 2 housed the Music Department. The two parts were reunited in 2013.[16]

Epiphany House

Epiphany House, 5 North Bailey, is a grade II listed house built around 1700 and acquired by the college in 2006 to house undergraduates.[14][17]

Lightfoot House

Lightfoot House, 19 North Bailey (directly across the road from Durham Cathedral) is one of the buildings that comprise the college. It consists of two adjacent Grade II listed buildings that were constructed in the 18th century and have since been connected internally. The building is used as a hall of residence for first-year and third-year undergraduates. It is named after Joseph Barber Lightfoot, who was Bishop of Durham from 1879 to 1889.[18][19][20]

Langford House

Langford House, 21 North Bailey, is a grade II listed building built in the 18th century and named after a former Judaism scholar and College Chaplain. For many decades, it was the home of the College’s chaplains, but today is used as a hall of residence for third year (and some first year) undergraduate students.[18]

Grads House

Grads House, 22 North Bailey, is a Grade II listed building used as undergraduate accommodation. The building is largely late 18th-century, with a rainwater head dated 1796, but it contains a notable 17th century staircase. Its name derives from its use in the 1960s and 70s as a residence for students studying for postgraduate diplomas in Theology.[14]

Ramsey House

Ramsey House, 25 North Bailey, is a Grade II listed building built around 1820, now owned by the college and now used primarily for undergraduate accommodation. It is named for Arthur Michael Ramsey, the 100th Archbishop of Canterbury who was once resident in Ramsey House. He was also a member of the Governing Council for the college.

For many decades, Ramsey House was the home of successive college principals, but it is now given over to student accommodation. There are now seven student rooms and a self-contained flat, which is typically home to the artist-in-residence of St Chad's College. The Middle Common Room of the College is located on the ground floor.[21]

Trinity Hall

Trinity Hall is a former Durham School boarding house, located on Grove Street, across the river from the main college site. It was built in 1847 as the Second Master's House, later called Caffinites after Benjamin Charles Caffin, Second Master from 1863–1877, before becoming the school's junior house under the name Ferens House. It was acquired by the college in 2002 and converted into housing for 25 postgraduates and a house for the college principal. In 2017 the principal's house was converted into additional student accommodation.[22][23] From 2020, undergraduates were also housed at Trinity Hall.[24]

Hallgarth Street

30 Hallgarth Street, located across the river from the main college site, is a grade II listed building constructed around 1840. Formerly the college chaplain's house, it is now used as postgraduate accommodation.[25][23]

Libraries

There are three library rooms on the ground floor of Main College (the Bettenson Room and the Brewis and Williams Libraries). The Williams Library doubles as a multi-media room and is often used for meetings and lectures. There are two more libraries on the first floor: the Wetherall Library, which houses most of the theology and philosophy collections; and the Reserve Library, which contains the core curricula texts for all of the courses currently on offer in the university (as well as the special church history and liturgy collections). The Fenton Library and the Trounson Library, which opened in October 2006, are located on the third floor. Comprising three separate rooms, the Fenton and Trounson Libraries contain individual study carrels and are used primarily for private study. The college is unusual (in the Durham collegiate context) in the extent to which it has invested in libraries and study space.

The Durham University Library holds most of the college's medieval manuscripts and its oldest books, which include a number of 16th and 17th century imprints including Quintus Aurelius Symmachus's Epistolae familiares and the Concilia omnia.

Chapel

The college chapel, located behind Main College, was built in 1928, replacing an earlier chapel built on South Bailey in 1909. Intended only as a temporary building, the unheated wood-frame building seats 120 people and has been in continuous use. The chapel's contents are older than its structures, with older donated pews from various churches and a ballroom dance floor from a decommissioned ocean-liner.

Though still intended as only a temporary chapel, it is beautifully fitted up. Some day, when the permanent chapel is built, this and a good deal of the other furnishings can easily be transferred to the new building.

— C E Whiting (1932), The University of Durham 1832–1932[6]

The chapel is overseen by the college chaplain, an Anglican priest. The college's roots in the Catholic tradition of the Church of England are still evident in services in the college chapel. Chapel attendance is entirely voluntary, given that the college accepts students without regard to their religious background.

The college maintains a collegiate choral tradition, headed by the director of music. Membership in the college choir is by audition. The choir tours regionally and internationally and produces an annual CD of their music. The regional tours include regular visits schools in the North East, especially those on council estates, providing music workshops to students. The college offers a number of choral and organ scholarships every year.[26]

Boat House

The college's boat house is located on college-owned land on the banks of the River Wear, below the college's original home at 1 South Bailey, now part of St John's College. As of 2020, the college was planning to replace this with a new boat house, on the paddock below the current college site on North Bailey.[14]

Youth hostel

The main building and adjoining undergraduate accommodation become the Youth Hostels Association's hostel (for Durham) during the Easter and summer holidays.[27]

College life

Academic dress

Along with most Bailey Colleges, St Chad's students wear their college gowns to formal hall, matriculation, college congregations and other academic or formal events. The college gown is similar to others in Durham, with the addition of green cord across the edge of the vented sleeves (in practice most undergraduates' gowns do not have this feature). St Chad's also has retained its own distinctive academic hood (of black stuff with green lining and trim): previously designed for pre-1970s ordinands, the hood is today worn by graduates of the North East Institute for Theological Education and by honorary fellows. The rector has a distinctive robe (a full-sleeved gown of black corded silk, faced with silver-trimmed palatinate purple, and with sleeves lined with palatinate purple); college officers generally wear the academic regalia associated with their highest degrees.[28]

Matriculation

Though all Durham University students now participate in large matriculation ceremonies in the Cathedral, St Chad's has, for over a hundred years, conducted its own matriculation. This signals the fact that students are obliged to follow the regulations both of the university and of the college. Matriculands wear academic dress at the ceremony and every student signs the university's matriculation book, thereby sealing an oath to adhere to the rules and traditions of the college and the university.[29]

Advent procession

For over a half-century, the college has conducted an Advent procession in Durham Cathedral. The candle-lit choral service is unusual in not solely anticipating Christmas, but in anticipating the Second Coming, which is the traditional theological focus of the Advent season itself. The choir splits into two, with one group seated in the choir and the other processing from the entrance to the cathedral. The two groups call back and forth to each other, using chants based on the Great Advent Antiphons. These antiphons form the basis not only of the advent procession, but also of the popular advent hymn, "O come, O come, Emmanuel". The procession is advertised widely in the City of Durham; after the event the college hosts its annual reception for city residents.

Bars

The college bar won the "university bar" category of the 2009 Best Bar None awards for Durham City and held this title until the end of the 2009–10 academic year. St Chad's bar is one of the few remaining college bars still run by full-time undergraduate students elected by the student body.[30]

Societies and events

St Chad's College Boat Club (SCCBC) is the college rowing club and was founded in 1906. It operates from the college boathouse on the River Wear.

2011 has seen the re-establishment of a theatre company at St Chad's, Green Door Productions, which aims to promote all aspects of theatre within the college, be it acting, directing, set design or backstage work.[31] In 2011, Australian actor Russell Crowe visited the college to give a masterclass in acting.

Every year the college hosts a Candlemas Ball. Founded in 1956, this is one of the older and more flamboyant balls in the university. It is recognised, along with University College's June Ball, as being one of Durham's versions of the University of Cambridge's May Balls.

Formal hall

Twice a week throughout most of the whole academic year, members of the college don academic gowns and gather for formal hall. This tradition brings students and staff together, though fellows, tutors and their guests sit at high table. This not only enables students who are living out to visit college, but it enables the college to entertain official guests regularly.[32]

Feasts

The college has a number of feasts throughout the year. Both the Dining Hall and the Quad are used to provide a four-course meal for up to 250 people. Among the largest is the Principal's Feast, usually scheduled within a week or two of St Chad's Day. The Rector's Feast, a relatively new tradition, welcomes the rector to the college for a formal "visitation". The Domus Dinner is an annual gathering of college fellows along with college benefactors and guests. Feasts are often used to induct new fellows into the college.[29]

St Chad's Day

St Chad's Day features a day-long celebration (sometimes called a "gaudy" because of the formal proclamation of the day) and begins before sunrise with a noisy wake-up call: in the past, the students would 'invade' neighbouring colleges, waking them up as well; though after a particularly boisterous event in 2009, which garnered much unwanted attention from the student media, the college successfully reshaped the celebration. After a green breakfast, students wear green clothes and body paint to various events and challenges held throughout the day, gathering at noon for a run around Palace Green. Various musical and social events are held throughout the day and night.[29]

Arms and motto

The college's motto, non-vestra sed vos (literally "not yours but you") reflects the college's beginnings, when it sought to enable students of modest means to gain access to a university education. The motto commits the college to being concerned with the person, rather than with what the person owns.

Organisation and administration

Status

St Chad's is a "recognised college" of Durham University, but it is not maintained or governed by the university (St John's College has the same status). The college was originally licensed by the university as a hall of residence, becoming a college in 1919. The distinction between colleges and halls at that time was more a matter of style than substance, as nothing but the name changed. The college had argued for the change because it had gradually built up several endowed fellowships, which it thought were characteristic more of a college than of a hall (that said, other halls in Durham quickly followed suit without having such endowments). The term "recognised college" was first used in the 1937 statutes to refer to those colleges not maintained by the university. It remains an unusual arrangement and it means that, though most students at the college matriculate for degrees at Durham University, the college itself still remains a separate legal entity. A limited company and registered charity in its own right, it is financially autonomous, independently staffed and entirely self-governed. The governing body includes, among others, college staff and students, representatives of Durham University, of the Archbishop of York and of the bishops of Durham, Newcastle and Carlisle. All external representatives are appointed by the governing body itself (even if they are nominated by external bodies). All governors are legally obliged to further the interests of the college and they cannot privilege the interests of the bodies that nominated them.

In contrast, the university's "council colleges" do not have a separate legal identity and are actually owned, managed and governed directly by the university itself. The relationship between the two recognised colleges and the university proper is still unique to Durham and is for that reason often misunderstood. In contrast, Oxford and Cambridge colleges are generally constituent parts of the university via Royal Charter, as are the various colleges and institutes of the University of London.

The university's council (its governing body for non-academic matters) is forbidden by statute from having any "property in or financial responsibility for" the college. As the college no longer receives any direct public funds, it is generally reliant on its own ability to raise funds. Thus the generation of research income by resident research staff, the generation of conference income and the support of alumni are crucial for the college. As a consequence of this status, any formal or financial relations between the college and the university are effectively governed by agreements and contracts. Goods and services provided by the university to the college are charged for by the university; similarly, goods and services provided by the college to the university are charged by the college.

Notwithstanding its independence, the relationship between the college and the university is symbiotic. The university's council approves the appointment of the college's principal (this is chiefly because the principal is an ex officio member of Senate). If pressed this would effectively amount to a veto, but short-lists are invariably constructed in dialogue with the university. Again, though the university council does not have the power to approve or disapprove of any changes to the college's constitution, the college, in accepting recognition by the university, agrees to notify the university of any such changes. If those changes unfavourably affect the college's status in the university, recognition can be withdrawn, which is to say the college would remain but it would no longer be able to admit students to the university.

The college has a subsidiary trading arm, through which the college manages its non-academic activities. The status of the various institutes attached to the college varies, with some being wholly owned by the college, and others being partnerships or joint-ventures with outside bodies.

Governance

The college's visitor is the Archbishop of York, currently John Sentamu. The visitor exercises customary visitorial functions and is the court of final appeal for any matters referred to the archbishop by the governing body. The visitor is appointed by the governing body for a renewable five-year period. In matters regarding the university itself (such as those brought forward by students), the university's visitor has jurisdiction.

The college's rector is Michael Sadgrove, previously Dean of Durham and since 2016 Dean Emeritus of Durham. The rector is the titular head of the college, who has responsibility for monitoring the college's furtherance of its Anglican tradition and for interpreting college statutes. Ceremonially, the rector presides at many official functions in college: the role is akin to the chancellor's role in the university.

The college is governed by a twenty-member governing body, headed by Jonathan Blackie CBE, who retired in 2011 from his post as Regional Director of Government Office North East. Responsibility for purely academic matters is usually devolved to the council of fellows. The Principal, as chief executive, sits on both the governing body and the council of fellows. The majority of governors are lay members, which means they are from outside the college. The university and the dioceses of York, Durham, Newcastle and Carlisle all nominate governors, though they must be approved by the college's governing body.

Finance

The college has a modest endowment, which is enough to fund significant annual capital improvements, up to ten professorial fellowships and several dozen named scholarships. A private charity, as opposed to a public body, the college is ineligible for HEFCE (government) funding: around 12% of its income comes from charges to the university, a further 25% comes from research activities, with the rest raised through student fees, donations and conference income. The college is a registered charity. The college's turnover is £2.6 million and total assets in 2010 were £8 million (based on a deliberately conservative evaluation of the college's properties).[33] In 2008, the college's previous bursar, Christine Starkey, was jailed for fraud for having stolen close to a half-million pounds, which would otherwise have been in the college's endowment. Starkey had deposited into the bank proceeds from the conference and B&B trade, but she failed to put these monies through the college's accounts. She then transferred the funds directly from the college's account to her own, hiding the transfers in bulk bank-to-bank BACS transfers. Starkey's house was sold and the college was eventually successful in recovering all of the money that had been stolen.[34]

Admissions

Competition for membership in the college is strong and the college is the second most popular college (after the Castle) in Durham in terms of applications per place. Applications for postgraduate places similarly outnumber beds by a wide margin. Like other colleges, applicants are considered chiefly on the basis of academic merit, and 90% of undergraduates at St Chad's attain a first or upper second class degree.[35]

In the recent past, the college was one of four Durham colleges designated by the university to accept open postgraduate applications in all disciplines, though now virtually all colleges accept such applicants. St Chad's has a number of dedicated postgraduate residences and an unusually high percentage (more than 30%) of postgraduate students. The welfare of postgraduates is overseen by the college's Postgraduate Director.

Patronage

The governing body of the college has an advowson over ten benefices of the Church of England. Five are located in the Diocese of Liverpool (St Agnes', Toxteth; St Stephen's with St Catherine's; St Faith's, Great Crosby; St Paul's, Stoneycroft; and St Margaret's, Toxteth),[36] two in the Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich (Hadley (St Mary), and Wratting (Great and Little)[37] and one in each in the Durham (Longnewton), Hereford (Pontesbury) and Leicester (Syston) dioceses. Many of the advowsons were given to the college in the early twentieth century.[38] In the past, the patron would have had complete power to appoint the new priest; that power is now exercised jointly with the local bishop and parish (and often with other patrons).

Academic profile

Institutes

Though most Durham colleges are primarily residential rather than teaching institutions, St Chad's has its own research and academic staff. The college includes a number of institutes and research groups: the Durham Policy Research Group, a group of more than a dozen academics headed by professors Fred Robinson, Ian Stone and Tony Chapman, each of whom has his own research team. They advise on government policy and conduct primary research into regional development, regional economics and third sector activities. Other academics work full-time in the college but often in conjunction with various university departments (e.g. in the medical humanities). Still others work chiefly outside the college and university: for instance the filmmaker and professor Richard Else, in conjunction with Triple Echo Productions (a Scottish-based film production firm), works regularly with Traidcraft on behalf of the college.

Charitable activities

In addition to its primary charitable object of supporting students and scholars in Durham, the college works closely with Traidcraft, with whom it jointly promotes fair trade practices and offers the Traidcraft Fellowship. The college jointly sponsors the Ruth First scholarship, which annually enables a South African postgraduate student to study at Durham University. To widen participation, the college has created partnerships with a number of secondary schools in the North East and beyond and has worked with primary schools in the market town of Crook.

Collegiate studies

All Durham colleges are interdisciplinary, enabling staff and students to broaden their study and research interests. St Chad's runs a collegiate studies programme, which complements departmentally-based studies. The programme is explicitly justice-orientated, reflecting the ethos and history of the college. Students and staff are introduced to complex social issues in the North East of England through study tours and seminars; they are invited to participate in a weekly programme of training-events that go beyond traditional transferable skills to include such things as ethical decision-making and introductions to fair-trade practices, social accounting and eco-friendly life-strategies.

International dimension

In addition to the usual sports and cultural activities offered in most colleges, St Chad's has an international placement programme. Under the auspices of the Historic Schools Restoration Project, the college has a link with St Matthew's High School in Keiskammahoek, Eastern Cape, South Africa, where students and recent grads mentor and teach for up to four months, some also providing in-service subject-specialist support to staff. The South African project includes training with staff from St Andrew's College.

Notable people

College fellows

Joseph Cassidy was principal[39] of St Chad's from 1997 until his death on 28 March 2015. A Canadian social ethicist and Anglican priest, he was also a non-residentiary canon of Durham Cathedral. On 1 March 2016, Margaret Masson, previously Vice-Principal and Senior Tutor of St Chad's, was appointed Principal.

Senior college officers include the principal, the vice-principal/senior tutor, the chaplain, the directors of the various academic centres, the librarian, bursar and commercial director. In addition, St Chad's has over 30 college fellows, research fellows and research associates. There are over 50 college tutors who act as mentors for both undergraduates and postgraduates. The college offers a number of visiting fellowships to academics of all disciplines. A further 100 university staff associate themselves with the college, chiefly through membership in the Senior Common Room. The college awards honorary fellowships, usually to distinguished alumni of the college, but also to others who have made significant contributions to the college, the church or to public life.

List of principals

- 1904 Stephen R. P. Moulsdale (also Vice-Chancellor of Durham University, 1934–36)

- 1937 John S. Brewis (became Archdeacon of Doncaster)

- 1947 Theodore S. Wetherall

- 1965 John C. Fenton (became Canon and then Sub-Dean, Christ Church, Oxford)[40]

- 1978 Ronald C. Trounson

- 1989 David Jasper (became Dean of Theology, Glasgow University)

- 1991 Eric Halladay

- 1994 Duane Arnold[41]

- 1997 Joseph P. M. Cassidy

- 2016 Margaret Masson

Notable alumni

Matthew Amroliwala, BBC television newsreader

Matthew Amroliwala, BBC television newsreader Keith Getty, hymnwriter and composer (In Christ Alone, The Power of the Cross)

Keith Getty, hymnwriter and composer (In Christ Alone, The Power of the Cross)_(cropped).jpg.webp) John Hall, former Dean of Westminster and chaplain to Queen Elizabeth II

John Hall, former Dean of Westminster and chaplain to Queen Elizabeth II Patrick Hawes, a British composer, conductor, organist and pianist

Patrick Hawes, a British composer, conductor, organist and pianist Gwyneth Herbert, a British singer-songwriter, composer, multi-instrumentalist and record producer

Gwyneth Herbert, a British singer-songwriter, composer, multi-instrumentalist and record producer John Inge, Bishop of Worcester

John Inge, Bishop of Worcester John McManners, clergyman, historian of religion, and Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History at the University of Oxford

John McManners, clergyman, historian of religion, and Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History at the University of Oxford Tim Radford, British Army officer who serves as Commander Allied Rapid Reaction Corps

Tim Radford, British Army officer who serves as Commander Allied Rapid Reaction Corps Tim Willcox, BBC News presenter

Tim Willcox, BBC News presenter

|

|

Other notable associated people

John Galbraith Graham, best known as crossword compiler Araucaria, chaplain and tutor 1949-1952.

John Galbraith Graham, best known as crossword compiler Araucaria, chaplain and tutor 1949-1952. Michael Ramsey, the 100th Archbishop of Canterbury, resident fellow and governor

Michael Ramsey, the 100th Archbishop of Canterbury, resident fellow and governor Baroness Sherlock of Durham OBE, honorary fellow

Baroness Sherlock of Durham OBE, honorary fellow

- John Galbraith Graham MBE, noted British crossword puzzle compiler – 'Araucaria' of The Guardian

- Giles Ramsay – theatre director, producer and playwright, Fellow[58]

- Michael Ramsey (Baron Ramsey of Canterbury) PC – former College Tutor, Fellow, Governor and Visitor, Archbishop of Canterbury (1961–1974)

- Maeve Sherlock (Baroness Sherlock of Durham) OBE, awarded life peerage in May 2010, Honorary Fellow, former Chief executive of the Refugee Council and policy advisor to Gordon Brown

- David Stancliffe, Fellow, retired Bishop of Salisbury

Notes and references

- Mark Tallentire (18 February 2016). "New principal at St Chad's College". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Bruce Unwin (26 November 2017). "Durham college launches intern scheme to help keep talented graduates in North-East". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Term-Time Accommodation" (PDF). Durham University. 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Comparison stats re percent of first and upper second results over recent years. Over a hive- or ten-year period, the college's academic average is the highest among Durham colleges. In 2009, the college had the highest results in the university's history". Durham University. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "St Chad's Other Founder". The Chadsian (2018): 22–26.

- Whiting, C. E. (1932). The University of Durham 1832–1932. London: The Sheldon Press.

- "History". St Chad's College, Durham. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "St Chad's Church". Herrington Heritage. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Catalogue of Durham University Records: Colleges. Durham University Library. January 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "Term-Time Accommodation". Durham University. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- See College Archives, St Chad's College

- Historic England. "Castle wall behind Nos 16-22 (consecutive) and No. 22A (St.Chad's) (1121431)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Jenkins, Alistair. "Our Buildings". The Chadsian (2018): 8–9.

- "Buildings". St Chad's College. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Historic England. "1 and 2, North Bailey (1322884)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Leading human rights lawyer formally opens new Durham Law School building". Durham University. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Historic England. "5, North Bailey (1322846)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Buildings". St Chad's College. 30 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010.

- Historic England. "19 (North) North Bailey – commonly known as Lightfoot House "dark side" (1121425)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Historic England. "19 North Bailey – commonly known as Lightfoot House "light side" (1254243)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Historic England. "25 North Bailey (1121428)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Howarth Litchfield (2017). "Design Statement: Trinity House Durham for St Chad's College" (PDF). Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Accommodation". St Chad's College MCR. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Trinity Hall – Undergraduate & Postgraduate accommodation for 2020/2021". St Chad's College. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Historic England. "23–32, Hallgarth Street (Grade II) (1120617)". National Heritage List for England.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Durham | City Accommodation at St Chad University College". Yha.org.uk. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "University bursar forced to handover house sale cash". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "St Chad's College, Durham". Durham University. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "University Calendar : St. Chad's College". Durham University. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Catalogue of Durham University Records: Colleges". Durham University. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- The principal may also use the title "President". This title is used chiefly when abroad, and even then rather infrequently. In college the title "principal" is invariably used.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Nicholas Alan Chamberlain". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- Steve Easterbrook Wikipedia Page

- "The Queen's Birthday Honours 2017". Durham University Alumni. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Durham First : So what exactly lies between Gwyneth Herbert and her wardrobe?". Durham University. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "Queen's New Year Honours 2020". Durham University alumni. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Who's Who". Ukwhoswho.com. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "The Queen's Birthday Honours 2019". Durham University Alumni. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "NewsWatch | Tim Willcox". BBC News. 7 July 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ["Fellows". St Chad's College. Retrieved 5 April 2009. "Fellows"]. St Chad's College. Retrieved 5 April 2009.