Youth Hostels Association (England & Wales)

The Youth Hostels Association (England & Wales) is a charitable organisation, registered with the Charity Commission, providing youth hostel accommodation in England and Wales. It is a member of the Hostelling International federation.

YHA logo | |

| Abbreviation | YHA (England & Wales) |

|---|---|

| Formation | 10 April 1930 |

| Type | Voluntary sector |

| Legal status | Company limited by guarantee |

| Purpose | Youth accommodation and education |

| Headquarters | Matlock, England |

| Location |

|

Region served | England and Wales |

Membership | |

Key people | Margaret Hart (Chairman) James Blake (Chief Executive) |

Revenue | |

Staff | 1,232 (18/19)[1] |

Volunteers | 2,010 (18/19)[1] |

| Website | YHA website |

History

Formation

The concept of youth hostels originated in Germany in 1909 with Richard Schirrmann and it took 20 years for the ideas to reach fruition in the United Kingdom. In 1929/30, several groups almost simultaneously formed to investigate establishing youth hostels in the UK. Foremost among these was the Merseyside Centre of the British Youth Hostels Association. On 10 April 1930, representatives of these bodies met and agreed to form the British Youth Hostels Association.[2] Shortly afterwards, it became YHA (England & Wales), with separate associations for Scotland (Hostelling Scotland) and Northern Ireland (Hostelling International Northern Ireland).

YHA's charitable objective is stated as:

To help all, especially young people of limited means, to a greater knowledge, love and care of the countryside, and appreciation of the cultural values of towns and cities, particularly by providing youth hostels or other accommodation for them in their travels, and thus to promote their health, recreation and education.

Early years

The first hostel to open was at Pennant Hall near Llanrwst in North Wales. Opened in December 1930, it closed in 1931 due to problems with the water supply. The water came from a nearby brook but this was contaminated by sewage from the farm next door. As was commented at the time:

[the farmer] saw no sin in mixing manure with drinking water.[3]

1931 saw the first widespread opening of hostels and, by the end of 1931, 75 hostels had opened, although at the end of the year 15 closed their doors not to reopen.[4] The price of an overnight stay was 1/- (1 shilling) in every case.[5] Annual membership was 5/- for Seniors and 2/6 for Juniors. Life membership was available for 3 guineas (£3 3s). Of the hostels opened in 1931, two remain open, Idwal Cottage and Street.

All hostels provided accommodation in single-sex dormitories, usually with bunk beds. Most hostels had accommodation for both sexes, but in a few towns, including Southampton, separate hostels were provided for men and women.[6] Self-catering facilities were provided at all hostels and many hostels provided a meals service.

Each hostel was run by a manager known as a warden and all the hostels in an area were administered by a number of Regional Councils. Initially, there were 14 Regional Councils, but the number grew to 19 by the end of 1935.[7] A National Office to co-ordinate policy and standards was established in Welwyn Garden City.

Membership was required to stay at a hostel and everyone staying was required to assist in the running of the hostel by undertaking what were known as 'duties'. These ranged from washing up to cleaning the hostel and, in hostels with no water supply on site, replenishing the water supply.

Blankets and pillows were supplied. A sheet sleeping bag was used from the outset and could be hired for a small charge, but most members chose to provide their own, carrying it with them from hostel to hostel.

The emphasis was very much on a communal atmosphere within each hostel. The use of dormitory accommodation and common rooms in every hostel reinforced this. Also the shared interests, mostly walking and cycling, of those using the hostels contributed to this spirit.

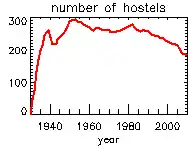

From this rough and ready beginning, the organisation grew and grew so that, by the outbreak of World War II, there were 297 hostels and 83,000 members, with 600,000 overnight stays being recorded.[8]

It did not take long for the fledgling organisation to obtain royal approval and in 1932 the then Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) opened Derwent Hall hostel in Derbyshire.[9] With its panelled walls, it became a flagship hostel for the Association.

Wartime reduction

The war had a significant effect on YHA. Membership levels in 1940 and 1941 slumped as men and women joined the armed services and leisure travel was discouraged. The number of hostels open decreased, with up to a third being closed for the duration due to their location in militarily sensitive areas. The low point was 1941, when only 170 hostels remained open[10] and overnight stays were reduced accordingly. It was not only the war that led to the closure of hostels: among the hostels that closed for good was Derwent Hall, flooded as a result of the Derwent Water Board project and the creation of Ladybower Reservoir.

From the low of 1941, things began to recover, so that by war's end over 200 hostels were open and membership was back to pre-war levels. This increase in the latter part of the war was partly due to government encouragement for factory workers to take short breaks away from the cities.

Post-war recovery

With peace, the resurgence of YHA continued until, in 1950, the peak number of hostels open was reached, with 303 open in that year.[11] Membership continued to grow and passed the 200,000 mark in 1950.[11] Overnight stays grew from 1.1 million in 1950 to 1.45 million in 1970.[12]

In 1955, the National Office moved from Welwyn Garden City to St Albans, where it remained until 2002 when a further move was made to Matlock. The buildings in St Albans and Matlock were both called Trevelyan House in honour of the first president of YHA, Dr G. M. Trevelyan.

In 1964, the number of regions was reduced to ten and financial changes made to make it easier for each region to manage its own affairs.[12]

Reform

Significant modernisation of hostels had occurred during the 1970s, but by the early 1980s it became clear to YHA that it needed to change, as the stresses and strains of running what was a large organisation began to show on what was almost entirely a volunteer-run body. Direct management of the hostels was removed from the regional committees and a professional management structure was put in place.[13] The regional committees were themselves reformed into four regional councils; North, Central, South and Wales.

With a new management, YHA continued to thrive and by 2000 overnight stays had reached a new peak of over 2,000,000.[14] Reflecting changes in the needs of young travellers, much effort was put into meeting a desire for less spartan facilities in hostels, such as smaller rooms, more showers, and the abolition of washrooms.[13]

As well as upgrading facilities in existing hostels, other experimental approaches to attracting young travellers were made. In 2000, a series of summer-only hostels utilising university student accommodation were opened in locations near airports such as Luton and Leeds. The experiment was not repeated in following years.

A much more successful innovation was the introduction of the RentaHostel scheme. Under this scheme, groups could hire whole hostels for their own use and without normal hostel rules applying. Rentahostel was available during the winter months to improve usage of hostels that were otherwise closed or doing very little business. The scheme continues to run to the present day but is now known as Exclusive Hire.[15]

Foot-and-mouth disease crises – 2001

The 2001 United Kingdom foot-and-mouth disease crisis hit YHA hard. An estimated £5,000,000 of income was lost[16] as a consequence of hostels being closed and a drop in overnight stays from just under 2,000,000 to 1,667,000.[17] Some hostels, such as Baldersdale, were totally inaccessible as they were within quarantine zones. This left YHA in a serious financial crisis and severe measures needed to be taken. The board of trustees agreed to sell 10 hostels at the end of 2002,[18] the sites being Aysgarth, Linton (North Yorkshire), Dufton, Elton, Buxton, Copt Oak, Thurlby, Norwich, Windsor and Holmbury St Mary. Internal and local pressure saved Dufton and Holmbury St Mary from closure and Thurlby was sold to Lincolnshire County Council who rented it back to YHA to continue as a hostel.[19]

21st century

The YHA charitable object has changed over the years, most recently in 2005 when the objective was changed to: "To help all, especially young people of limited means, to a greater knowledge, love and care of the countryside, and appreciation of the cultural values of towns and cities, particularly by providing youth hostels or other accommodation for them in their travels, and thus to promote their health, recreation and education."

YHA has been investing in its youth hostels. Investment is funded largely from turnover. Donations, legacies and funds from other organisations, agencies and individuals also contribute. Since 2006, YHA has invested £48.5 million and opened six new youth hostels: Whitby, North Yorkshire; National Forest, Derbyshire; Berwick-on-Tweed, Northumberland; Castleton, Derbyshire; on the South Downs near Southease in East Sussex, and in London.[20]

In 2006, YHA announced the largest plan of network renewal.[21] YHA regularly monitors all its hostels to establish if they are still viable and if necessary closes those that are no longer viable or have no prospects of becoming viable again in the future.[22] However, the network renewal project was on top of this regular review and was a proposal to close and dispose of 32 hostels when it was announced. The aim of the exercise was to reduce borrowing and to provide funds for re-investment into the network. The closures were to take place over a three-year period, over and above the 13 others disposed of in the same period. The hostels involved were not necessarily poor performers but ones where the amount of investment required to bring them up to a desired standard was excessive (e.g. Steps Bridge) or in some cases because the site value was very high (e.g. Stainforth). When the news broke, there was a storm of protest not only among the membership,[23] but also in local communities[24] and local and regional government.[25] Despite the protests, YHA proceeded with the plan. Some hostels, such as Liverpool, have obtained reprieves either temporary or permanent and are still open, but most of the other disposals have taken place. A number of the hostels disposed of have reopened, either as independent hostels or as Enterprise[nb 1] hostels within YHA.

In 2008, as part of the move towards raising standards, YHA replaced the traditional sheet sleeping bag with a fitted bottom sheet, duvet cover and pillow cases. From 2015, guests at most youth hostels found their beds already made for them. At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, YHA had a network of around 140 youth hostels. In the previous ten years, YHA had sold or not renewed the leases on 86 properties. Of these, 21 continued to run as part of the YHA network under a licensing scheme, YHA Enterprise. The sales of those properties netted YHA over £20 million,[26] but YHA continued to make a small operating loss.[26] The value of the property portfolio as of February 2010 prices was £77.15 million.[27]

In May 2010, YHA announced that, in a further realignment of the network and to support long-term financial stability called the "Capital Strategy", two new hostels would open in 2010 and eight would close. The two new hostels were Southease in Sussex and Berwick on Tweed. Those closed were Capel Curig (Gwynedd), Exeter (Devon), Grasmere Thorney Howe (Cumbria), Hunstanton (Norfolk), Kendal (Cumbria), River Dart (Devon), Saffron Walden (Essex), and Scarborough (North Yorkshire).[28]

By the beginning of 2011, Capel Curig and Grasmere had both been sold and negotiations were in progress to sell the remainder (with the exception of Exeter – which was sold in 2013). On 8 February 2011, a further update to the "Capital Strategy" was announced that will see £4 million invested in the hostels at Black Sail (Lake District), Woody's Top (Lincolnshire), Wilderhope (Shropshire), Rowen (Snowdonia), Grinton Lodge (North Yorkshire), Salcombe (Devon), Poppit Sands (Pembrokeshire), Tintagel (Cornwall) and Wells-next-the-Sea (Norfolk). At the same time, the closure of a further nine hostels was announced, with the intention to begin the sales at the end of summer 2011. The hostels to close are Derwentwater, Helvellyn, Hawkshead (all Lake District), Osmotherley (North Yorkshire), Salisbury (Wiltshire), Arundel (Sussex), Totland Bay (Isle of Wight) and YHA Newcastle (Northumberland).[29]

In 2014, a new youth hostel opened in Brighton.[30] In 2015, a new youth hostel opened in Cardiff, which quickly became the only hostel in the YHA network to be awarded 5 stars by Visit Wales/Visit England. In December 2015, YHA Cardiff Central won Best Accommodation at the 2015 British Youth Travel Awards.

Publications and items

Handbook

In the first years of YHA (1931–1934), due to the rapid change in the number of hostels available, the handbook was issued more than once each year. From 1935, the pattern settled into an annual publication issued to all members. In 2003, this became a biennial publication. Since 2007, YHA has no longer produced an annual guidebook and relies on its website to show hostel information.

YHA magazines

The Rucksack was YHA's first magazine. First issued in 1932, it ran until 1956 when it was retitled The Youth Hosteller, although issue numbers continued the same series. Publication varied between quarterly in the early years to monthly in later years. The contents consisted of hostel reviews, travel articles, regional and local group news, a letters column and updates to the handbook. Publication ceased after the February 1972 issue (volume 39, no. 7, priced at five new pence, and reduced to bi-monthly appearance following December 1970), when an editorial explained that the magazine was to be "transmogrified".

The successor to The Youth Hosteller, Hostelling News ran from spring 1972 until summer 1985 (issue no. 54). A quarterly newspaper-style publication, free to members, it followed in much the same vein as its predecessors. Hostelling News was replaced in Autumn 1985 by YHA Magazine, a colour magazine in A4 format, which was rebranded as YHA Triangle in summer 1989 (issue no. 15) and which thereafter continued as a quarterly publication until autumn 1994 (issue no 31). From spring/summer 1995 (issue no 32) it became a biannual publication, continuing until the autumn/winter issue of 2006 (being the 55th issue, although no longer officially numbered as such). Following a further rebranding exercise, Triangle was replaced by the smaller-format Discover but this only lasted for three issues (spring/summer and autumn/winter 2007, and spring/summer 2008) before publication was put into abeyance.

In spring 2009, a shorter eight-page A4 colour publication YHA Life appeared (an undated four-page pilot version, with a focus on fundraising, was issued in 2008).

YHA News appeared between 1992 and 2005. Unlike all the other publications after spring 1972, which had been made available to all members, YHA News was only available by subscription. Its contents were much more aimed at those involved more actively with YHA. The opinions expressed were not necessarily those of YHA.

YHA has produced a monthly e-newsletter, "The Wanderer", since 2013.

Over the years, there have been many regional handbooks produced showcasing hostels in a particular region.

YHA Songbook

The YHA Songbook was first published in 1952. Common room sing-songs were popular and the songbook was published by YHA as:

Many a common room sing-song has been marred because few of the hostelers know more than the first verses of the songs, and all too frequently the item that begins as a rousing chorus ends as a faltering solo. A few keen singers find a place in their rucksack or saddle-bag for a song book, but if as a result some half-dozen song books are available, it is usually found that they are all different and even the songs that are in common to several appear in differing versions.[31]

The songbook only contained the lyrics, not the music, the assumption being that someone would know the tune.

YHA shops

YHA had from the beginning sold items directly necessary for using hostels, such as sheet sleeping bags, but in 1950 started selling goods for walkers, such as rucksacks, by mail order from National Office. By 1953, not only was an annual sales catalogue issued but YHA had opened a shop at 21 Bedford Street, London. Three years later, the shop moved across the Strand to John Adam Street. Over the years, this shop expanded into a Travel and Information Office[32] and other shops opened in major cities. In 1990, the store management bought the stores from YHA[33] and formed YHA Adventure Shops PLC. The company was wound up in 2004.[34]

Attitudes

Motor vehicles

From the earliest days, YHA made it clear that motorists were not welcome. Regulation 4 as printed in the handbook read:

Hostels are intended for Members when walking or cycling, and are not open to motorists or motor-cyclists (unless they are using the hostel for the purpose of walking or climbing. In any case motor-cars and motor-cycles must not be garaged at a hostel).[35]

Instead great emphasis in the handbook was placed on the availability of public transport with distances to nearest railway stations being given and the availability of bus services (something that continues to this day). In 1951 this point was promoted to regulation 1: "Youth Hostels are for the use of members who travel on foot, by bicycle, or canoe; they are not for members touring by motor car, motor cycle, or any power-assisted vehicle".[36]

By the mid 1960s, with the decline in rail services, YHA allowed members to use cars to reach a hostel, but not to motor tour. It remained policy that cars could not be parked at hostels. From 1970 it was decided to allow parking, for a fee, at certain hostels. However hostel wardens had a discretion to require people arriving by car to move on if the hostel was busy. In 1984 car parking charges were abolished, and parking allowed at all hostels, subject to space.

Membership

Until 2005 it was a requirement to be either a member of YHA or a member of an Hostelling International affiliated association before staying at a hostel. YHA relaxed this rule partly due to a desire to make hostels more accessible to all and partly due to advice received from the Charity Commission that the charitable status of the association was at risk if it remained a membership-only organisation.

Membership can be purchased on arrival at a hostel. Non-members have been able to stay since 2005; it was originally stated that this was "by paying a £3 supplement to the normal overnight price ... – equivalent to a day rate for membership".[37] This was later amended to the form of a standard price for everyone, with a £3 per night, subsequently 10%, discount for members on booking directly.[38]

Alcohol

Until the 1980s consumption of alcohol was not allowed; drinking at the hostel could lead to offenders being banned from the hostel. The ban was initially lifted only for alcohol purchased at hostels with a table licence such as Edale, but later it was permitted to bring and drink beer, cider and wine (not spirits), but only accompanying a meal.

With the reform of UK licensing laws the responsibility for the behaviour of customers falls onto the personal licence holder, i.e. the hostel manager. Citing the risk of prosecution of its staff, YHA introduced a policy,[39] whereby only alcohol purchased at the hostel was permitted to be consumed on the premises. For hostels not licensed for the sale of alcohol, the previous policy on bring-your-own continues.

The majority of youth hostels have been licensed to sell alcohol since 2010 and some have a bar.[40]

Schools

Pre war, groups of children aged 11–18 were welcome at hostels as long as they were under the supervision of a responsible leader. All bookings had to be made in advance. Apart from price no other concession was made to these groups. They were still expected to move on from hostel to hostel and for this reason this type of business became known as School Journey Parties (SJP).

After the war YHA realised the potential of providing not just accommodation to school parties and youth groups but educational facilities as well. This scheme Youth Hostels for Health and Education, started in 1953[13] and was the forerunner of the services offered today. In 2008, 27% of overnight stays with YHA were as part of organised school trips.[41]

YHA provides financial support via its bursary scheme, Breaks for Kids, for groups of young people to take part in educational or recreational visits. In 2013 YHA awarded grants totalling £238,000, providing 5,754 funded trips for young people.[42]

Notes

- Enterprise hostels are hostels that are privately owned but operated as part of the YHA under a licence agreement with YHA

Footnotes

- "Charity overview". apps.charitycommission.gov.uk.

- Coburn p. 18.

- Coburn p. 29.

- Neal & Neal

- YHA Handbook, 4th edition 1931. Welwyn Garden City: YHA. 1931.

- YHA Handbook 1939. Welwyn Garden City: YHA. 1939.

- Maurice-Jones & Porter p. 47.

- Coburn p. 187.

- Maurice-Jones & Porter p. 9.

- Coburn p. 88.

- YHA Annual Report 1998/9. St Albans: YHA. 1989.

- A Short History of the YHA. St Albans: YHA. 1969. ISBN 978-0-900833-02-1. OCLC 71021.

- "YHA History". Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- YHA Strategic Plan 2008–2013. Matlock: YHA. 2008.

- "YHA Exclusive Hire". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Foot and Mouth lessons learned inquiry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- Cook, Stephen (3 July 2002). "Bitter suites". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "Ten youth hostels to close doors". BBC News. 13 March 2002. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "Thurlby back in business". Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Annual reports

- "Network renewal gets green light". Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- A full list of all hostel openings and closing since 1931 is at List of past and present youth hostels in England and Wales

- "YHA Closures". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "Campaign launched to save Ivinghoe youth hostel". Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "AMs unite against hostel closure". BBC News. 26 April 2006. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "Annual reports". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "2010 Charity overview to the Charities Commission". Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- "Investing in the Future". YHA. 11 May 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- "YHA's Capital Strategy". YHA. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Dixon, Rachel (22 November 2014). "Five of the best British youth hostels". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- YHA Songbook. St Albans: YHA. preface

- YHA Handbook 1975. Matlock: YHA. 1974.

- "YHA Adventure Shops". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "YHA ADVENTURE SHOPS PLC". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- YHA Handbook of Hostels 1935. Welwyn Garden City: YHA. 1934. p. 18.

- YHA Handbook 1951. St Albans: YHA. 1950. p. 14.

- "YHA Open to all". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "YHA Membership – Sign up and save!". www.yha.org.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Changes to bring your own". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- YHA website

- YHA Annual Review 2008 (PDF). Matlock: YHA. 2008. p. 28.

- news release

References

- Coburn, Oliver (1950). Youth Hostel Story. London: National Council of Social Service.

- Maurice-Jones, Helen; Porter, Lindsey (2008). The Spirit of YHA. Matlock: YHA.

- Neal, Tim; Neal, Simon (1993). Youth Hostels of England and Wales 1931–1993. St Albans: YHA. ISBN 0-9522254-0-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Youth Hostels Association (England & Wales). |